Introduction

The Black-crowned Night Heron is a crepuscular and nocturnal bird, most often seen at dusk as it flies to its feeding grounds. They are colonial breeders, forming dense groups with dozens of nests to a tree, also in association with other heron species (Hothem et al. 2020). In Virginia, the species is a fairly common summer breeder and migrant in the Coastal Plain region but is rare and localized inland (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Breeding Distribution

Within the Coastal Plain, the Black-crowned Night Heron was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Therefore, there was no need to model its distribution within that region. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

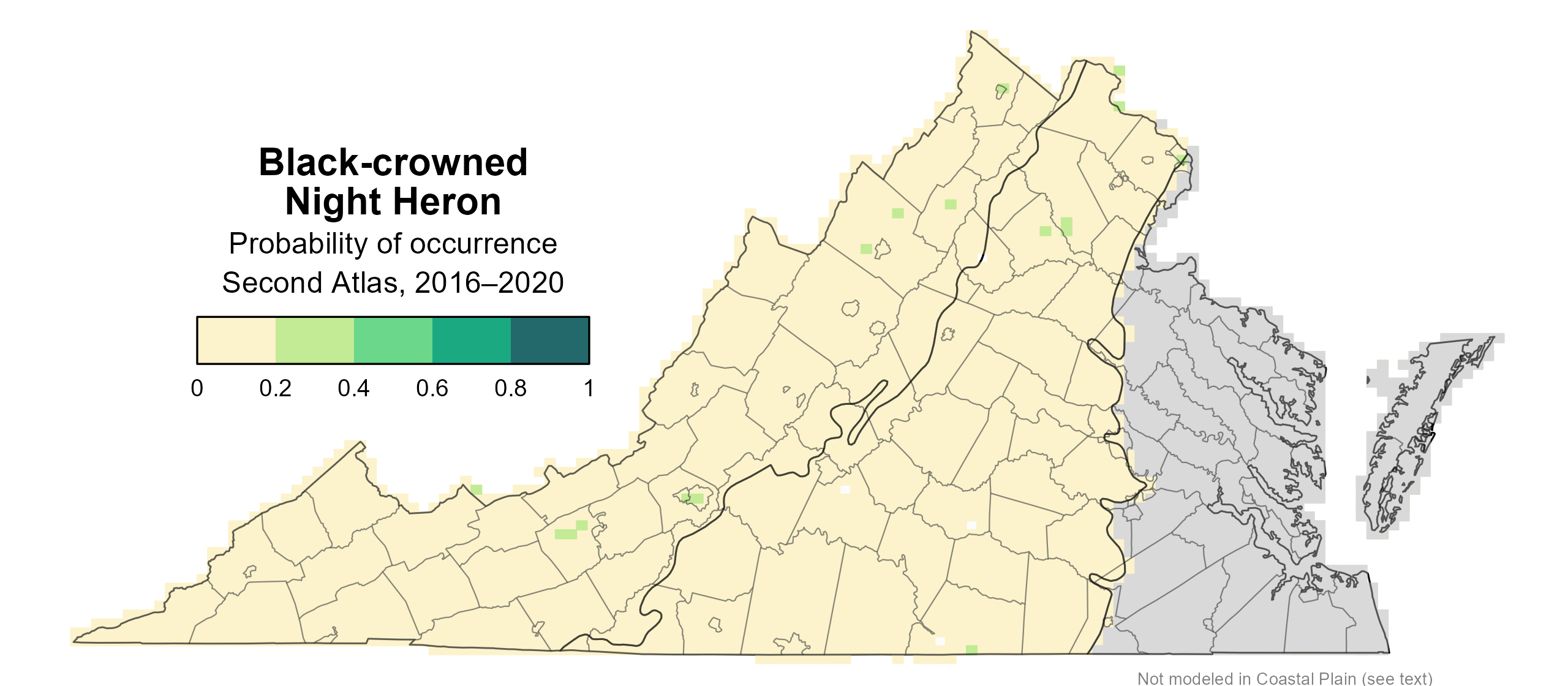

Outside of the Coastal Plain, Black-crowned Night Herons are most likely to occur in isolated pockets inland in the Shenandoah Valley (Figure 1). Additionally, they occur patchily along riparian corridors in the western montane region of the state. The likelihood of observing this species increases largely as a function of observation effort. It should be noted that waterways, an important land feature for colonial waterbird foraging and nest placement, could not be included in the model due to limitations in the available landcover data.

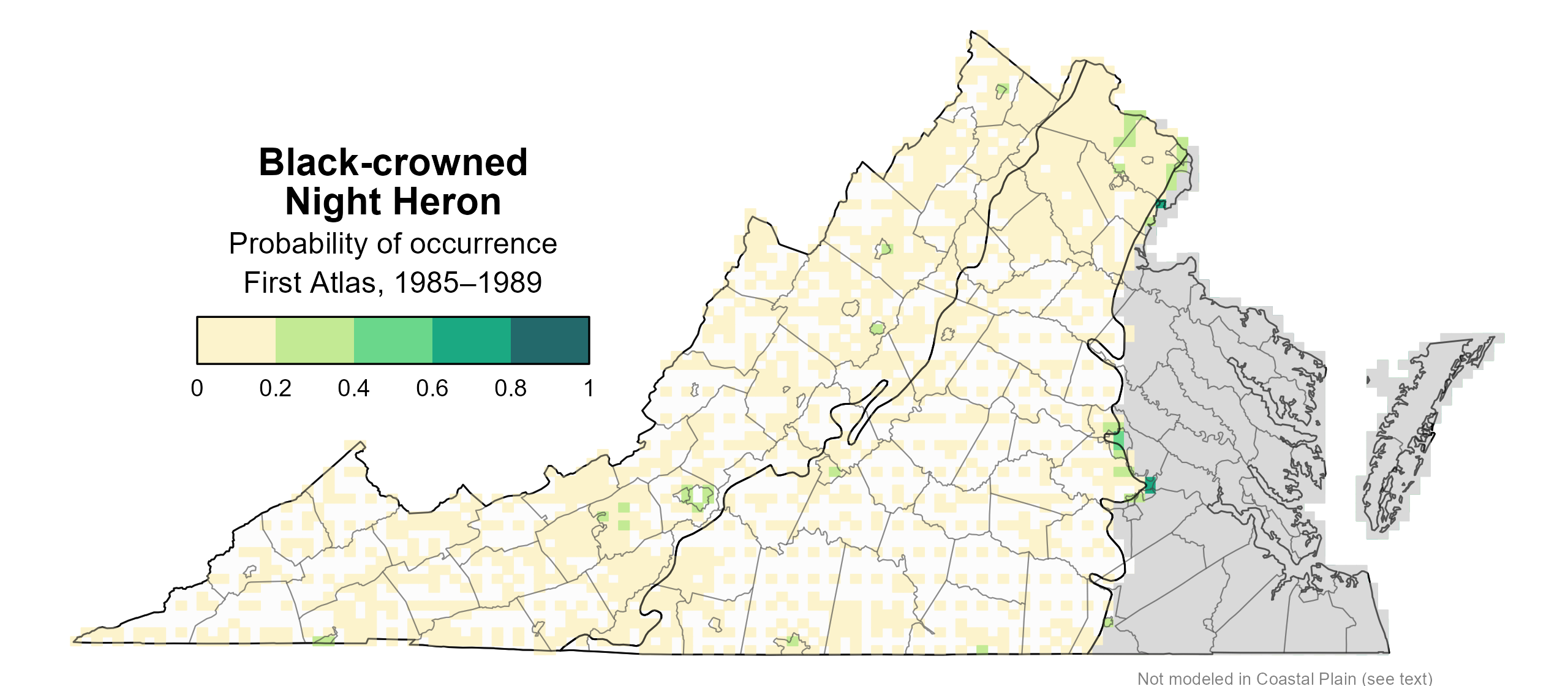

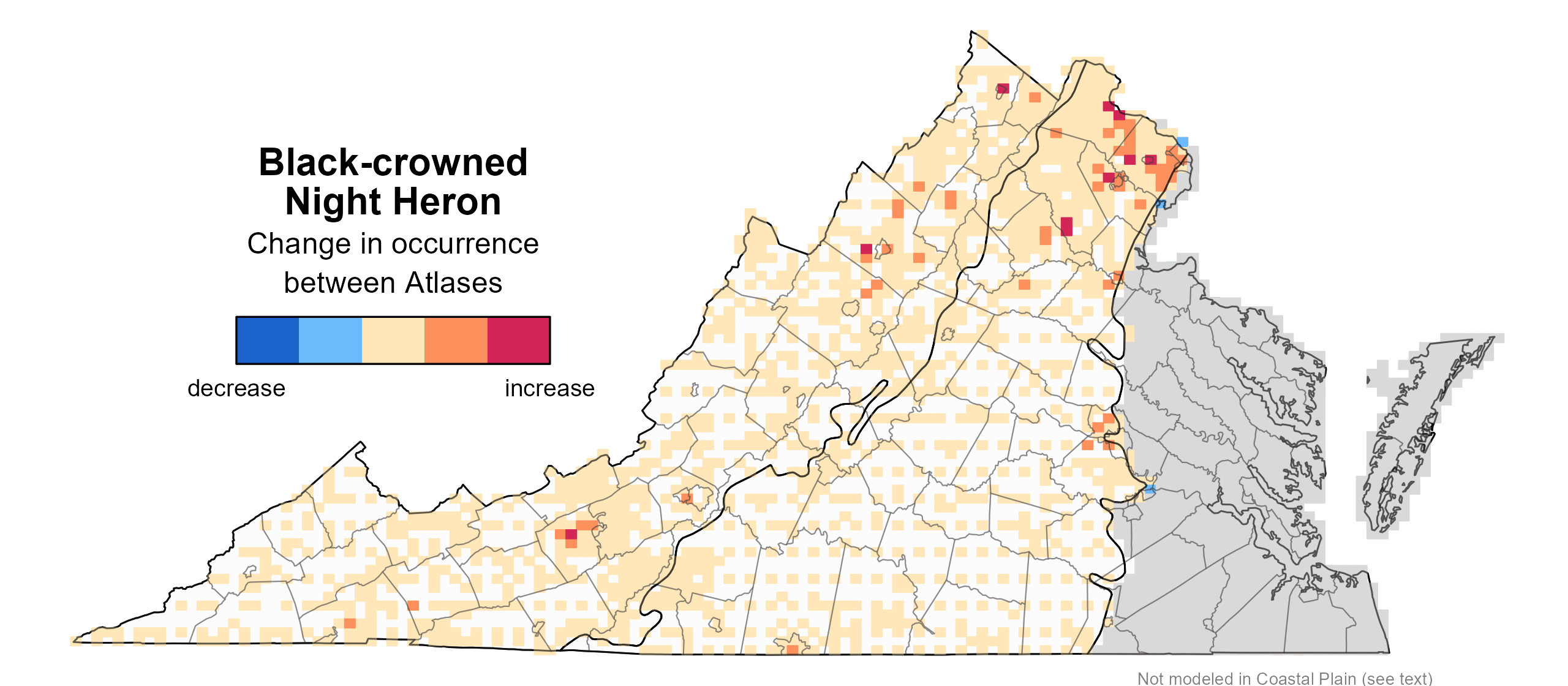

Black-crowned Night Heron’s probability of occurrence increased slightly in the Northern Virginia area and remained generally the same throughout the remainder of the Piedmont region and the Mountains and Valleys region (Figures 1 to 3).

Figure 1: Black-crowned Night Heron breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 1: Black-crowned Night Heron breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 3: Black-crowned Night Heron change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas so were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

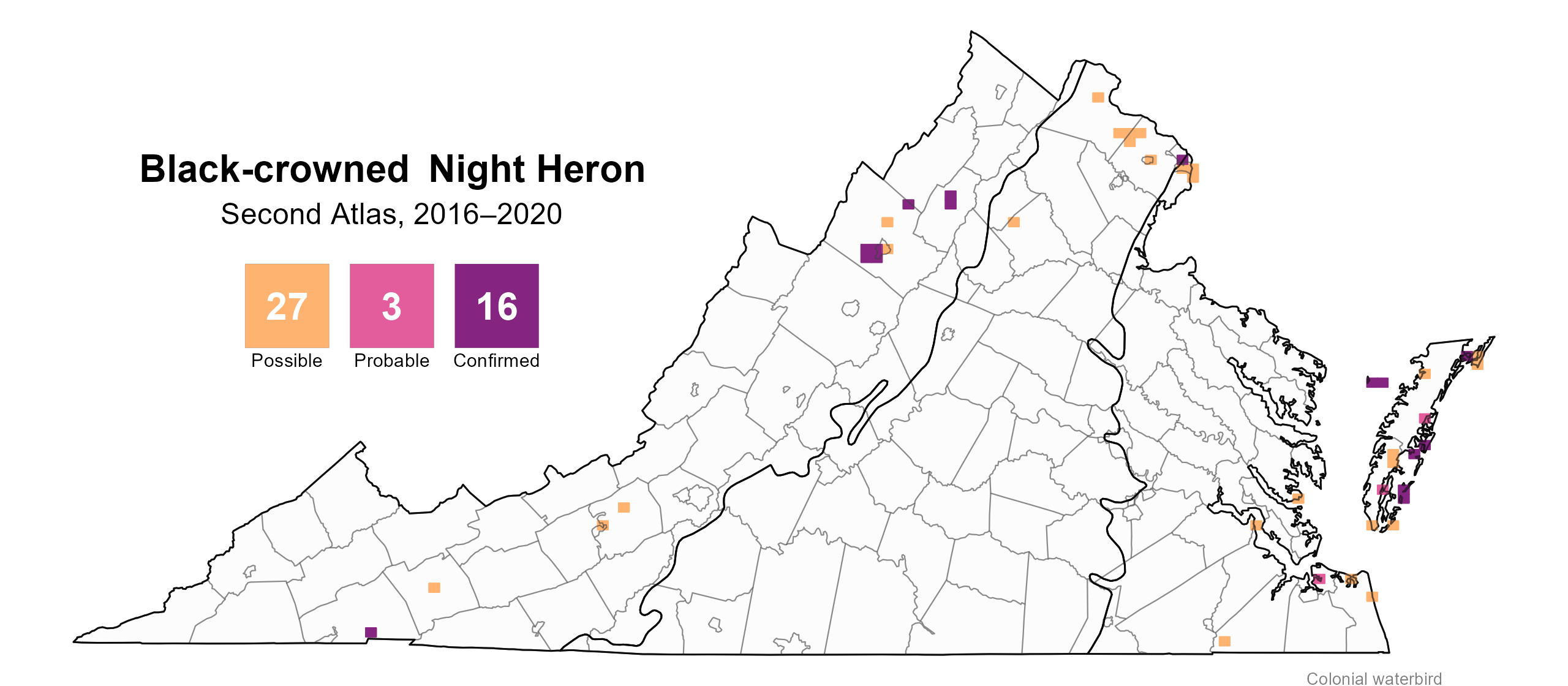

Given that the locations of nesting colonies were documented by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018, Black-crowned Night Herons in the Coastal Plain are unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence. There were additional breeding confirmations reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period. Outside of the Coastal Plain, where there is no systematic survey to identify nesting colonies, the nesting status of the species in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence is less clear.

Black-crowned Night Herons were confirmed breeders in the Coastal Plain and Mountains and Valleys regions in 16 blocks and eight counties and were probable breeders in one additional county (Figure 4). In the Coastal Plain, confirmations were recorded only on the Eastern Shore, where colonies were located on the Chincoteague Island Causeway and nearby marshes, Tangier and Watts Islands in the Chesapeake Bay (Accomack County), and several Atlantic barrier islands (Northampton County). The densest concentrations of nests were at Chincoteague and Cobb Island (Watts et al. 2019). In the Mountains and Valleys region, they nested in Luray (Page County), Harrisonburg, and Dayton (Rockingham County).

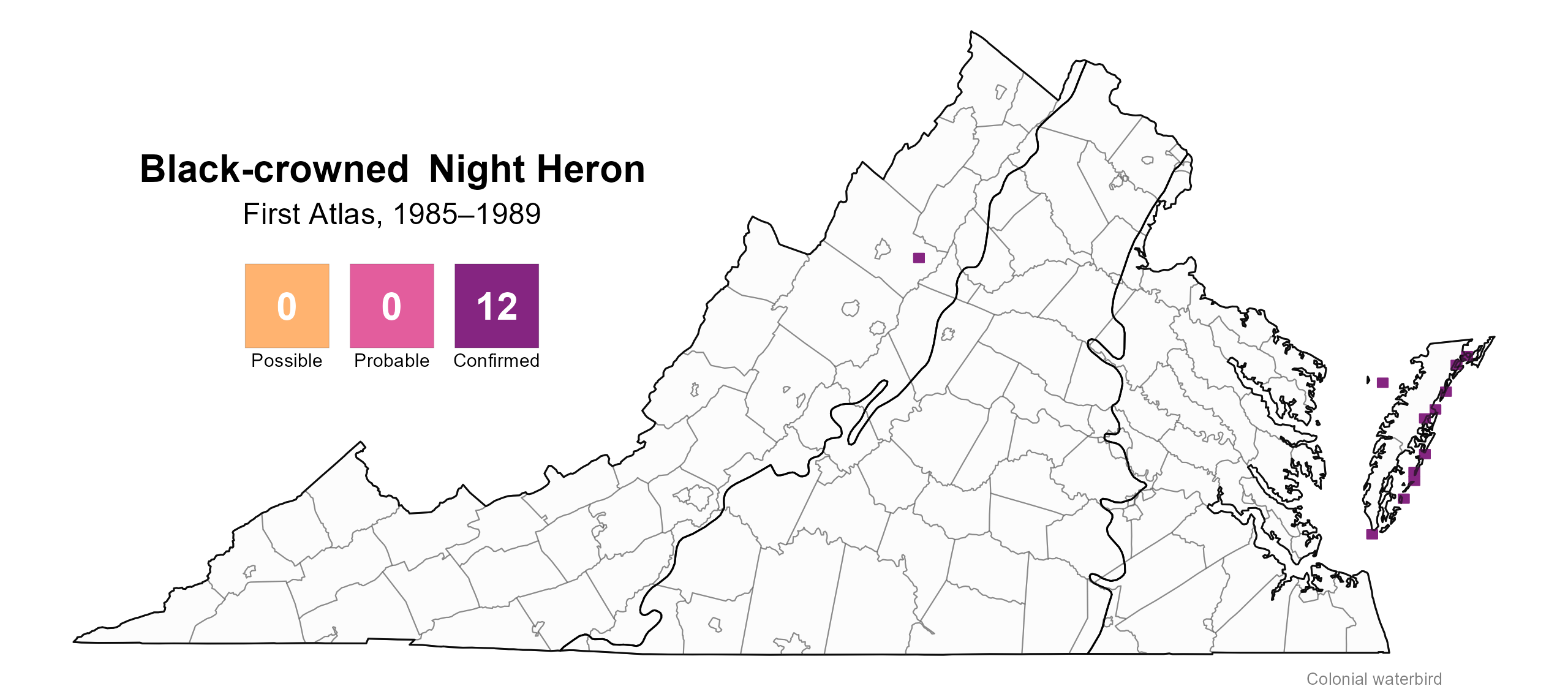

During the First Atlas, the species was similarly confirmed in the Coastal Plain and at one location in Rockingham County in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 5).

Nest building began in mid-April and continued through mid-May (Figure 6). Young were in the nest from mid-May through July 31, and fledglings were observed through August 20. Rookeries should not be closely approached for risk of disturbance; thus, only one observation was made of eggs in the nest. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Black-crowned Night Heron, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Black-crowned Night Heron breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 5: Black-crowned Night Heron breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Black-crowned Night Heron phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Black-crowned Night Heron had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Black-crowned Night Heron colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

In terms of its population trend, the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys surveys show that the breeding population of Black-crowned Night Herons in coastal Virginia declined by an estimated 80% between 1975 and 1993. However, in more recent decades, this trend has reversed, with a 63% increase in breeding pairs from 1993 to 2018 (Watts et al. 2019). In 2023, the estimated number of breeding pairs rose to 1,545, an 80% increase between 2018 and 2023 (Watts et al. 2024).

Figure 7: Black-crowned Night Heron population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Black-crowned Night Heron sits atop the aquatic food chain, and thus, they are susceptible to pollutants including persistent organochlorine pesticides, PCBs, and heavy metals. They make an excellent sentinel for environmental contamination in urban environments (Hothem et al. 2020). They are also at risk of habitat loss due to sea-level rise and changes in precipitation, both of which can reduce the availability of their shallow marsh habitat and alter the distribution of their prey and predators, affecting where they occur on the landscape (Hothem et al. 2020). Protection, acquisition, and restoration of inshore high marsh habitat should be a priority to help slow or offset the loss of nesting habitat due to sea-level rise.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hothem, R. L., B. E. Brussee, W. E. Davis Jr., A. Martínez-Vilalta, A. Motis, and G. M. Kirman (2020). Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bcnher.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, Virginia, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-19-06. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-24-12. Williamsburg, VA, USA.