Introduction

The Peregrine Falcon is truly a master of the sky: it tops the list of the world’s fastest animals for the prodigious speeds that it achieves while diving after prey and delights observers with its daring aerial maneuvers during both courtship and territorial defense against larger raptors. This crow-sized falcon is easily recognized by its dark crown and “sideburns”, plumage features that are shared across ages and sexes.

The Peregrine Falcon has a nearly worldwide breeding distribution, and in the eastern United States, it was historically found nesting on cliff faces in the Appalachian Mountains prior to its decline and subsequent recovery (Hickey 1942). It is drawn to sites with certain characteristics, including a commanding view of the surrounding landscape and open habitats for foraging. Some of its eyries (nest sites) have been used by breeding pairs across decades. Although Virginia’s cliff-nesting population is making a comeback, the Peregrine Falcon otherwise mostly nests on artificial structures, including towers, bridges, industrial smokestacks, and high-rise buildings (Watts and Watts 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Hovering at north of 30 pairs (Watts and Watts 2024), the known breeding population of Peregrine Falcon in Virginia is too small to develop a model to predict its broader distribution within the state. The species is distributed across all three of Virginia’s ecoregions, although the majority of breeding pairs nest in the Coastal Plain (Watts and Watts 2024). Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

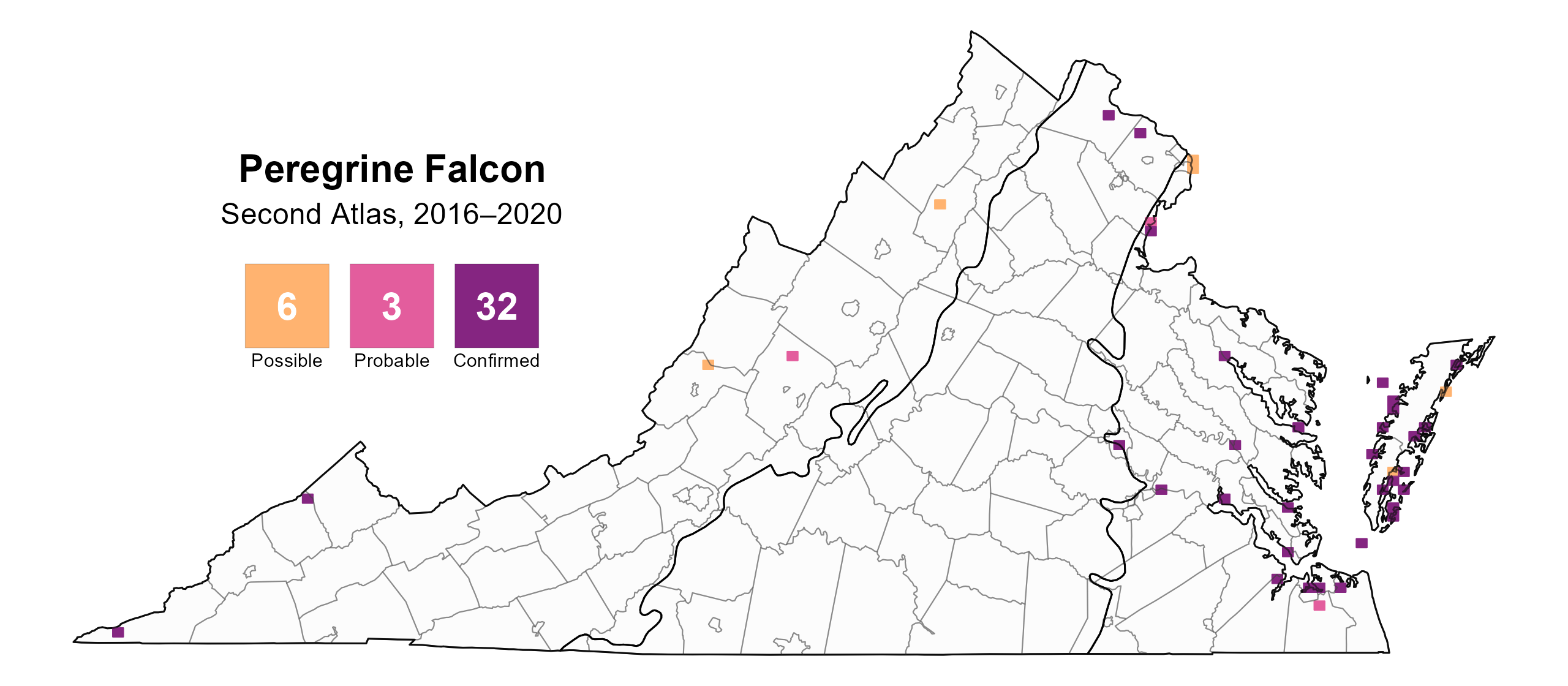

Peregrine Falcons were confirmed breeders in 32 blocks and 21 counties and found to be probable breeders in two additional counties (Figure 1). There were two confirmed nests in the Mountains and Valley region (Dickenson and Lee Counties) and two in the Piedmont region (a quarry in Loudon County and a high-rise building in Fairfax County). The remaining nests were located throughout the Coastal Plain region, with a concentration on the Eastern Shore.

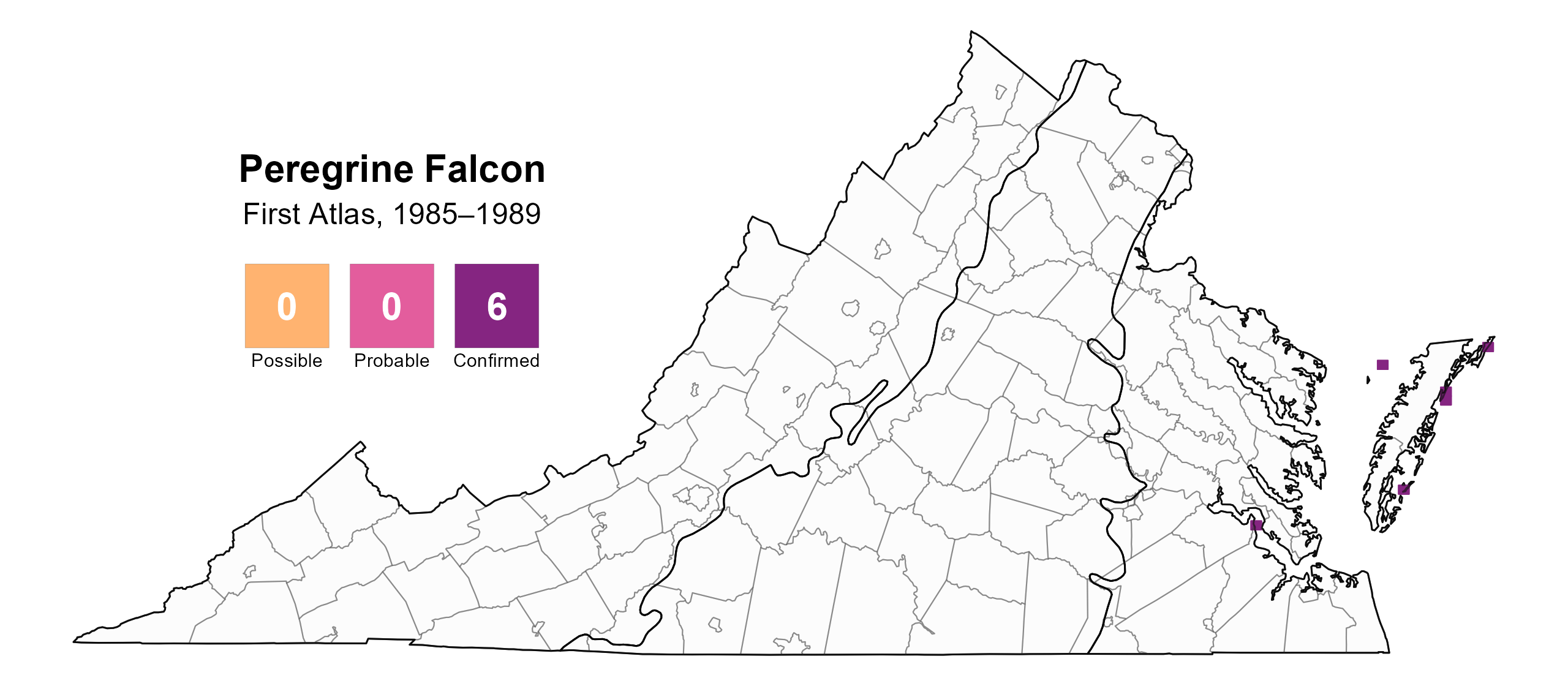

The distribution of breeding pairs has grown greatly since the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). The First Atlas began in the last year of coastal releases of captive-raised birds (see Conservation section), a time when Peregrine Falcon pairs had just recently begun establishing themselves and the number of known occupied territories did not exceed twelve (Watts et al. 2018).

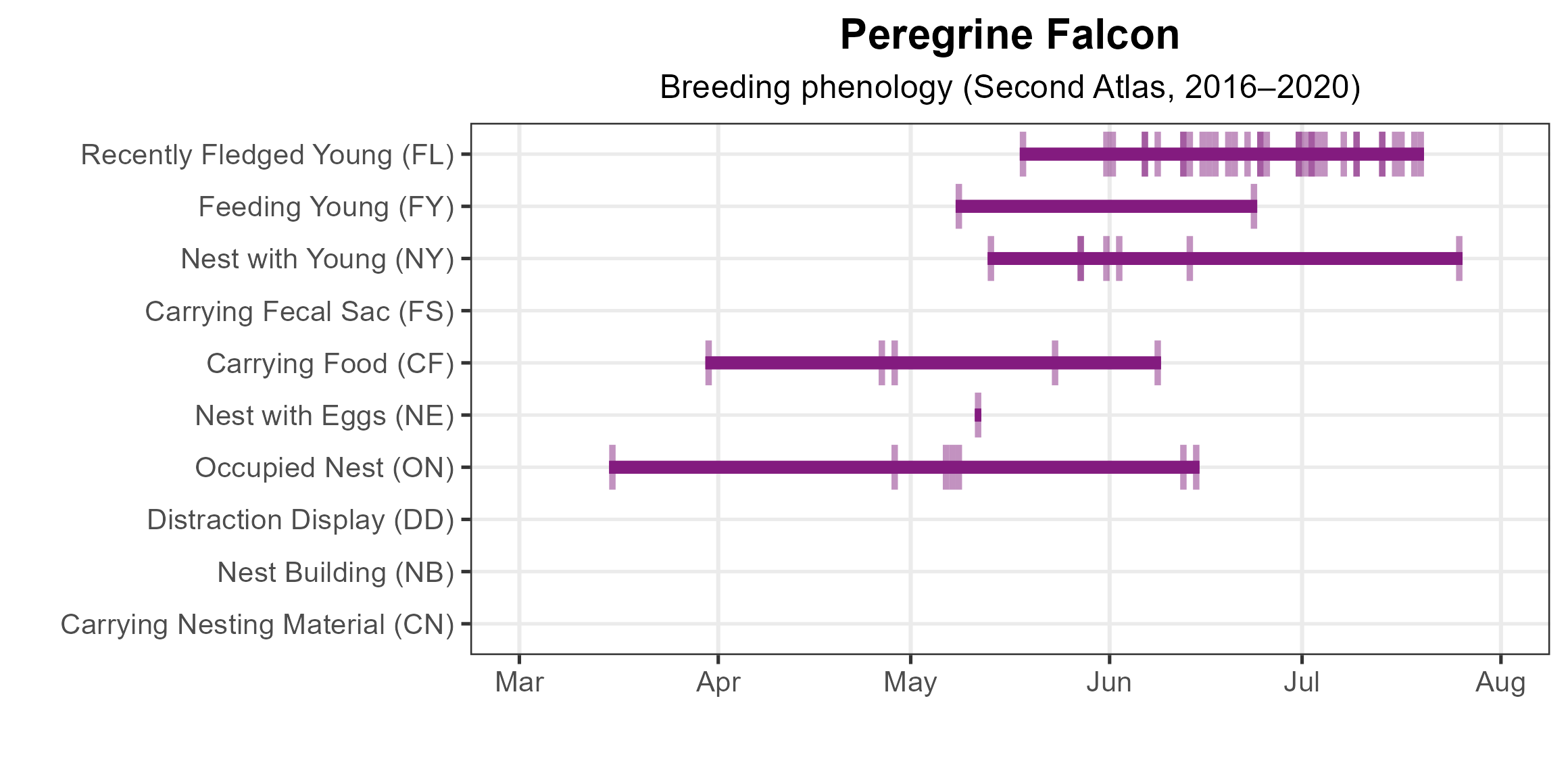

The earliest breeding behavior recorded was an occupied nest on March 15. However, breeding was confirmed mainly through observations of recently fledged young (May 18 – July 19) (Figure 3). Most nesting records were the result of monitoring of the Peregrine Falcon breeding population, which is conducted annually by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) at the College of William and Mary and its partners. Based on those data, Peregrine Falcons in Virginia typically lay their eggs in March; this is followed by up to six weeks of incubation and another seven weeks before fledging.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Peregrine Falcon breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Peregrine Falcon breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Peregrine Falcon phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Given its status as an apex predator with a small population size, modeling the abundance of Peregrine Falcons is not possible nor meaningful for Virginia. The population has been steadily increasing since the first pair re-established nesting in 1982 following reintroduction efforts (Watts and Watts 2020). The breeding population in 2024 consisted of 34 documented pairs, including 24 in the Coastal Plain region, five in the Piedmont region, and five in the Mountains and Valleys region (Watts and Watts 2024). This number may be an underestimation, as additional pairs are likely breeding at cliff sites in the mountains, as well as in quarries that have not yet been surveyed.

Conservation

Prior to the early 1960s, the Peregrine Falcon was known to breed across multiple mountain sites within Shenandoah National Park, in or near the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, and in several locations in southwestern Virginia (Gabler 1983). Two nest sites were also documented on the Eastern Shore. The population in Virginia and throughout the species’ range declined rapidly from the 1950s onward, owing to widespread use of organochlorine pesticides such as DDT (Watts et al. 2015; Watts and Watts 2020). This decline led to the federal listing of two subspecies of the falcon. Following a ban of DDT in 1972, widespread reintroductions across the Peregrine Falcon’s range were successful in recovering the two subspecies, which were both delisted by 1999.

The last historic Peregrine eyrie in Virginia was active in the early 1960s. Subsequent reintroduction of the Peregrine Falcon in the Commonwealth involved the release of 242 captive-reared birds from 1978 to 1993 in both the Mountains and Valleys and Coastal Plain regions. Since the first successful nest in the early 1980s, the species has undergone a spectacular recovery, with most nest sites concentrated on artificial structures in the Coastal Plain. The Peregrine Falcon remains listed as state threatened by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) in recognition of the small number of breeding pairs in its historic nesting stronghold, the Mountains and Valleys region. Due largely to its small population size, it is also classified as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). The CCB’s monitoring of the Virginia Peregrine Falcon population focuses on the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions (Watts and Watts 2020), while VDWR leads monitoring efforts at natural cliff faces in collaboration with multiple partners.

The Peregrine Falcon population continues to expand in Virginia. The species was recently discovered nesting in quarries (Watts and Watts 2019), and its population continues to grow at natural cliff sites in the mountains, reaching a modern high of seven sites in 2025 (Sergio Harding, personal communication). Expanded survey effort will be necessary to properly document breeding pairs at both types of sites, which can be challenging due both to their sheer number (quarries) and remoteness (cliff sites). In the Coastal Plain, the success of Peregrine Falcons on the Eastern Shore has created pressure on sensitive shorebird populations, including migrating Red Knots (Calidris canutus), whose rufa subspecies is listed as federally threatened. However, the falcon itself may now be facing a new threat from highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), which is potentially implicated in the loss of some of its breeding territories on the Eastern Shore (Bryan Watts, personal communication) and in coastal New Jersey in 2024 (Kathy Clark, personal communication), as well as in recently documented declines in multiple western states. HPAI surveillance in Peregrine Falcons and other species by VDWR and partners will be critical in evaluating the scope of this emerging threat.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Gabler, J. K. (1983). The peregrine falcon in Virginia: survey of historic eyries and reintroduction effort. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 81 pp.

Hickey, J. J. (1942). Eastern population of the Duck Hawk. The Auk 59:176–204.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B, K. E. Clark, C. A. Koppie, G. D. Therres, M. A. Byrd, and K. A. Bennett (2015). Establishment and growth of the Peregrine Falcon breeding population within the Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain. Journal of Raptor Research 49:359–366. https://doi.org/10.3356/rapt-49-04-359-366.1.

Watts, B. D.; M. A. Byrd, E. K. Mojica, S. Padgett, S. R. Harding, and C. A. Koppie (2018). Long-term monitoring of a successful recovery program of Peregrine Falcons in Virginia. Ornis Hungarica 26:104–113. https://doi.org/10.1515/orhu-2018-0018.

Watts, B. D., and M. U. Watts (2019). Virginia peregrine falcon monitoring and management program: year 2019 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-19-13. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 25 pp.

Watts, B. D. and Watts, M. U. (2020). Virginia Peregrine Falcon monitoring and management program: year 2020 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Reports, 676. William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D. and M. U. Watts. 2024. Virginia Peregrine Falcon monitoring and management program: year 2024 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-24-21. William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 22 pp.