Introduction

The second smallest falcon in North America, the Merlin has expanded its eastern breeding range southward from Canada in recent decades (Warkentin et al. 2020). It was confirmed breeding in Virginia for the first time in 2021, months after data collection for the Second Atlas ended.

Merlins do not build their own nests, using old hawk and crow nests instead. They are generally associated with open to semi-open forested areas (Warkentin et al. 2020), and in Virginia, they have bred in suburban settings with residential homes, small woodlots and scattered tall trees. Though it has a varied diet that includes insects and small vertebrates, the Merlinʼs preferred prey is small birds (Johnston 2000; Warkentin et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Because the Merlin is currently known as a breeder from only two sites in Virginia, occupancy models could not be developed. Please see the Breeding Evidence sections for more information on its breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

During the Second Atlas, Merlins were reported from just two locations as possible breeders: Great Falls Forest in Loudon County and Metompkin Island in Accomack County (Figure 1). They were confirmed to be nesting in Virginia for the first time in 2021. A pair nested in a suburban area in the town of Christiansburg in Montgomery County, using an old crow’s nest and fledging three young. Following a nest failure in 2022 due to a depredation event on the breeding female, the pair has gone on to nest in the same area each year, fledging three young in 2023 and at least three young in 2024. In 2025, a second nest site was confirmed in Wise County, following the delivery of a grounded juvenile Merlin to a wildlife rehabilitator in Roanoke.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Merlin breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

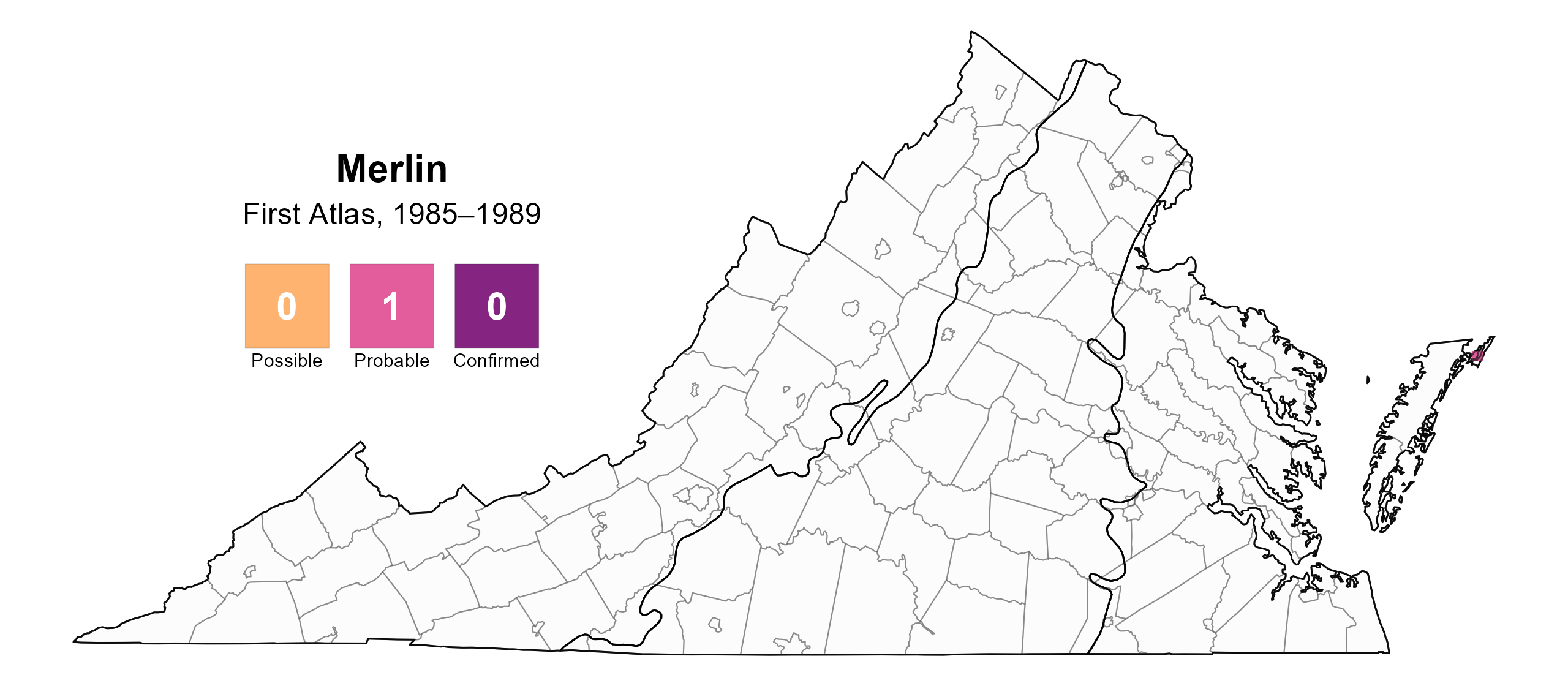

Figure 2: Merlin breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Population Status

Abundance models were not developed for Merlin due both to a lack of data (only a single detection during Atlas point count surveys) and, until very recently, to the status of the species as a nonbreeder in the Commonwealth. Credible breeding population trends for the species cannot be estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) at any geographic scale, based on its relatively low abundance along BBS routes.

Conservation

Virginia is currently at the southern end of the Merlin’s breeding range expansion from Canada into the eastern U.S. The species first bred in New York and northern New England in the mid-1990s, with subsequent first breeding confirmations in Pennsylvania in 2006 (Warkentin et al. 2020) and in West Virginia in 2009 (though there exists one previous breeding record 1888) (Bailey and Rucker 2021). The Pennsylvania population currently stands at approximately 150 breeding pairs (Don Nixon, personal communication).

The presence of two breeding pairs separated by over 100 miles in the Commonwealth increases the likelihood that there are additional undetected pairs already breeding here. As in more northern states, expansion of the species as a breeder in Virginia may have been facilitated by an increase in individuals capable of nesting in more urban environments (Warkentin et al. 2020).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, R. S., and C. B. Rucker (Editors). (2021). The second atlas of breeding birds in West Virginia. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, USA. 568 pp.

Johnston, D. W. (2000). Foods of birds of prey in Virginia, part I, stomach analyses. Virginia Natural History Society, Banisteria 15. https://virginianaturalhistorysociety.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/28/2022/12/Banisteria15_Raptor-prey-items-1.pdf.

Warkentin, I. G., N. S. Sodhi, R. H. M. Espie, A. F. Poole, L. W. Oliphant, and P. C. James (2020). Merlin (Falco columbarius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.merlin.01.