Introduction

The Brown Pelican is one of only two non-white pelican species in the world, along with the Peruvian Pelican (Pelecanus thagus), which is sometimes considered a subspecies of the Brown Pelican. Its expandable throat pouch can hold several gallons of water (and fish), roughly three times the capacity of its stomach. This species is distinctive for its dramatic, headfirst dives into the water to catch prey.

Historically rare in Virginia, the Brown Pelican has undergone a significant expansion in the past 50 years. Beginning in 1977, individuals began lingering through the summer, with annual increases in sightings until nesting was first confirmed in 1987 at Fisherman and Metompkin Islands (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

From 1970 to 2009, the Brown Pelican was listed as federally endangered. Today, it is a thriving symbol of our coastal waterways. It is easily observed cruising just above the water or roosting in lines on sandbars and the concrete ships at Kiptopeke State Park.

Breeding Distribution

The Brown Pelican was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Brown Pelican only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

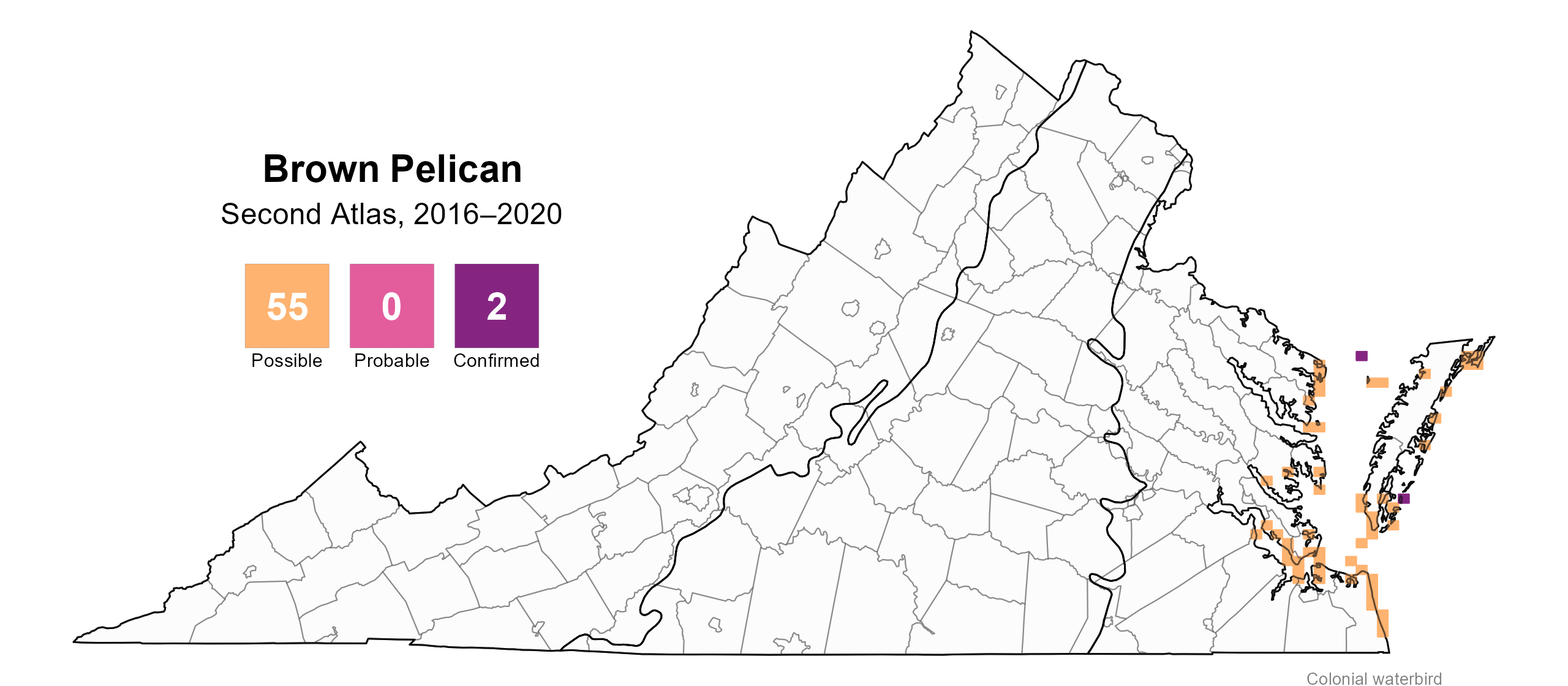

Brown Pelicans nest exclusively within the survey area covered by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018, and this survey documented the locations of breeding colonies of this species. Therefore, the species is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

Brown Pelicans were confirmed breeders in two blocks solely in Accomack and Northampton Counties (Figure 1). In the northern Chesapeake Bay, they nested alongside Double-crested Cormorants (Nannopterum auritum) at South Marsh on Shanks Island in Accomack County. In Northampton County, along the seaside, a colony was documented on Wreck Island.

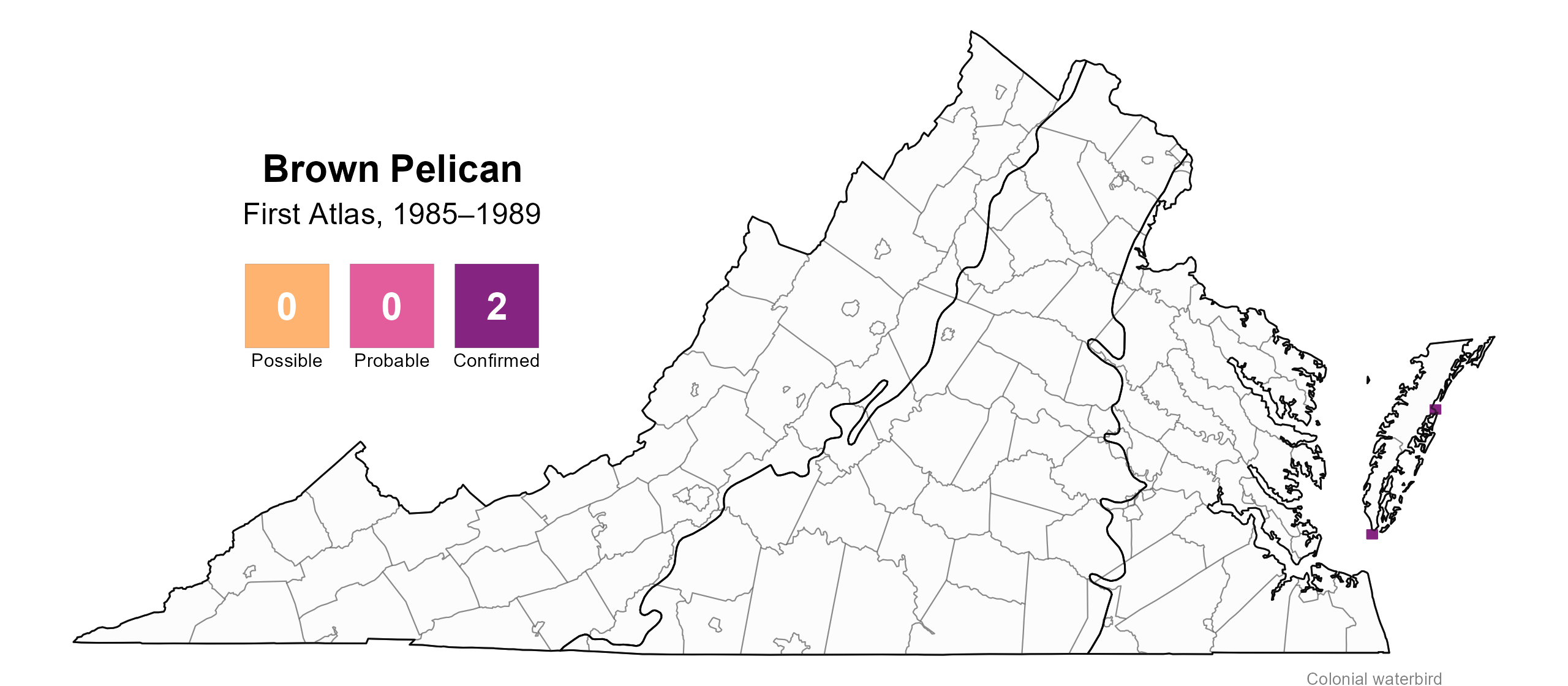

During the First Atlas, Brown Pelicans were newly discovered breeders recorded only in two blocks, at Fisherman Island and Metompkin Island (Figure 2). These sites were not occupied during the Second Atlas, but breeding distribution on Virginia’s barrier islands is highly dynamic with colony locations frequently shifting between years (Watts and Paxton 2014).

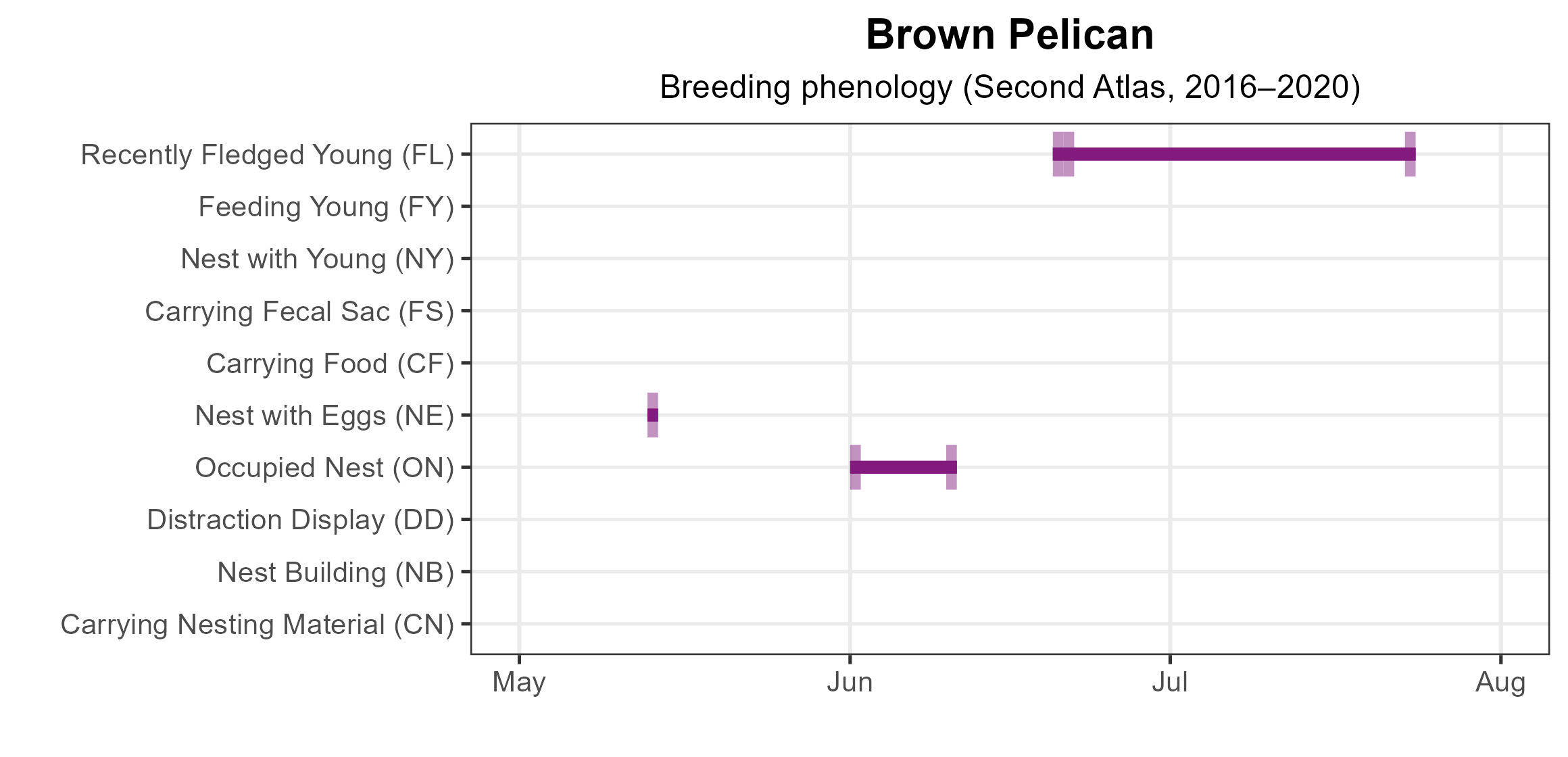

Due to the small number of colonies and their often inaccessible locations, breeding phenology is poorly documented. Nests with eggs were observed as early as May 13, and occupied nest continued to be observed through June 10 (Figure 3). Young birds, sometimes seen away from colonies, were recorded from June 20 to July 23.

As a colonial species, Brown Pelicans are underrepresented in Atlas data. Only the highest breeding code is submitted per site, and multiple nests within a colony are not individually recorded. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Brown Pelican, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Brown Pelican breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Brown Pelican breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Brown Pelican phenology: confirmed breeding codes (Second Atlas). This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Brown Pelicans had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Brown Pelican colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys show steady population growth since the species was established, largely driven by immigration and some turnover between sites. From just a few pairs in 1987, the population increased to 368 pairs by 1993 and peaked at 3,246 pairs in 2018 (Watts et al. 2019). By 2023, however, the number had declined to 2,609 pairs, a 20% decline, due to habitat loss and sea-level rise, particularly at Shanks Island in the northern Chesapeake Bay (Watts et al. 2024; Figure 4).

Despite this recent decline, the Brown Pelican remains one of Virginia’s most numerous colonial breeding waterbirds.

Figure 4: Brown Pelican population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

From near-extirpation in North America, the Brown Pelican has made a remarkable recovery.

During their decline in the 1960s–1970s, the major threats were DDT and other organochloride pesticides such as Endrin (Wilkinson et al. 1994; Shields 2020). The species was listed as federally endangered in 1970 and began to recover following pesticide bans and legal protections. It was delisted on the East Coast in 1985 and fully delisted nationwide in 2009.

As a colonial nester, Brown Pelicans are vulnerable to disturbance. Fortunately, Virginia’s breeding colonies are largely insulated from human interference. Wreck Island is closed to visitors during the summer, and the Shanks Creek colony is remote. However, improperly discarded monofilament fishing line, hooks, and lead tackle remain significant threats, with sport fishing gear a major source of mortality (Shields 2020).

Rising seas bring more frequent storm events, high tides, and flooding, which degrade or eliminate nesting habitat. At Shanks Island, erosion has already caused substantial population declines for both Brown Pelicans and Double-crested Cormorants, accounting for much of the observed decline in Virginia between 2019 and 2023.

Despite these challenges, the Brown Pelican continues to expand along the Atlantic Coast and appears to have a stable future in Virginia. The species is even establishing colonies in more urbanized areas, such as the Fort Wool barge complex, which was built to replace habitat lost to the expansion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (Watts et al. 2024; Sweeney et al. 2024). Future monitoring and protection of nesting sites, serve to protect pelicans alongside the rest of the beach-nesting bird community.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Shields, M. (2020). Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.brnpel.01.

Sweeney, C., K. Hunt, J. Fraser, and S. Karpanty (2024). Assessing avian response to the relocation of Virginia’s largest seabird colony, 2024 annual report. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-19-06. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-24-12. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Wilkinson, P. M., S. A. Nesbitt, and J. F. Parnell (1994). Recent history and status of the Eastern Brown Pelican. Wildlife Society Bulletin 22:420–430.