Introduction

One of three falcon species that occur regularly in Virginia, the American Kestrel is the smallest, most colorful, and most numerous. As a grassland bird, it is often seen perched on fences, utility lines, and tree snags throughout rural and, increasingly, suburban Virginia, where it hunts small mammals and insects. The kestrel is easily identified by its silhouette and bobbing tail (Smallwood and Bird 2020).

American Kestrels are cavity nesters, using natural cavities or those excavated by woodpeckers, rather than excavating their own. Kestrels also readily use nesting boxes and sometimes nest in buildings, such as barns. Recently fledged young can occasionally be seen with their parents, as they practice hunting before becoming fully independent (Smallwood and Bird 2020).

Breeding Distribution

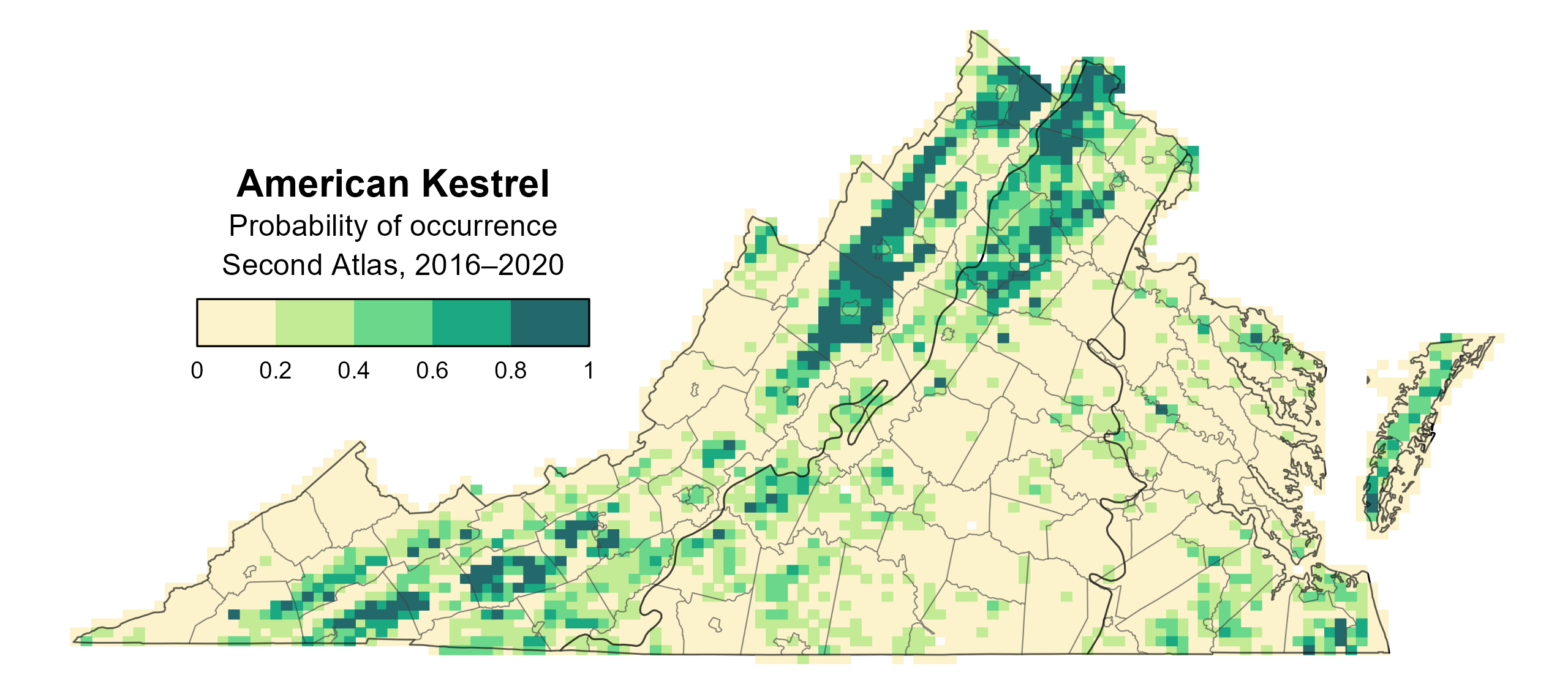

While American Kestrels breed across Virginia, their core breeding distribution is centered in agricultural valleys in the Mountains and Valleys region, suburban and rural areas of the northern Piedmont, and, to a lesser extent, the southeastern corner of the Coastal Plain and the Eastern Shore (Figure 1). Across this landscape, they are more likely to be found in blocks with a higher proportion of pastures and hayfields but also have a positive, albeit weaker, association with development. Confirmation of breeding during the Atlas in fact included records from within the cities of Harrisonburg and Roanoke (see Breeding Evidence section), and there have been post-Atlas reports of fledglings in downtown Richmond (Sergio Harding, personal communication). American Kestrels are less likely to be found in blocks containing a greater diversity of habitat types.

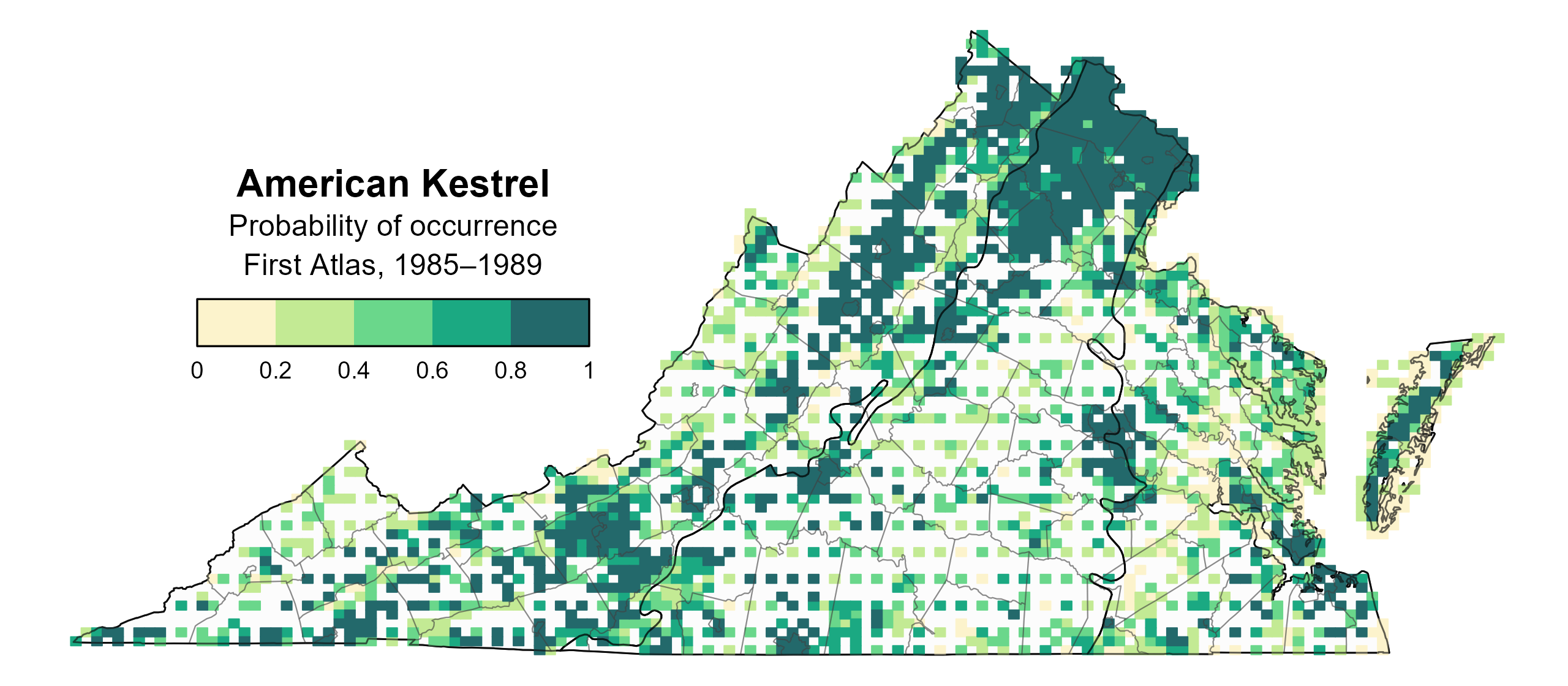

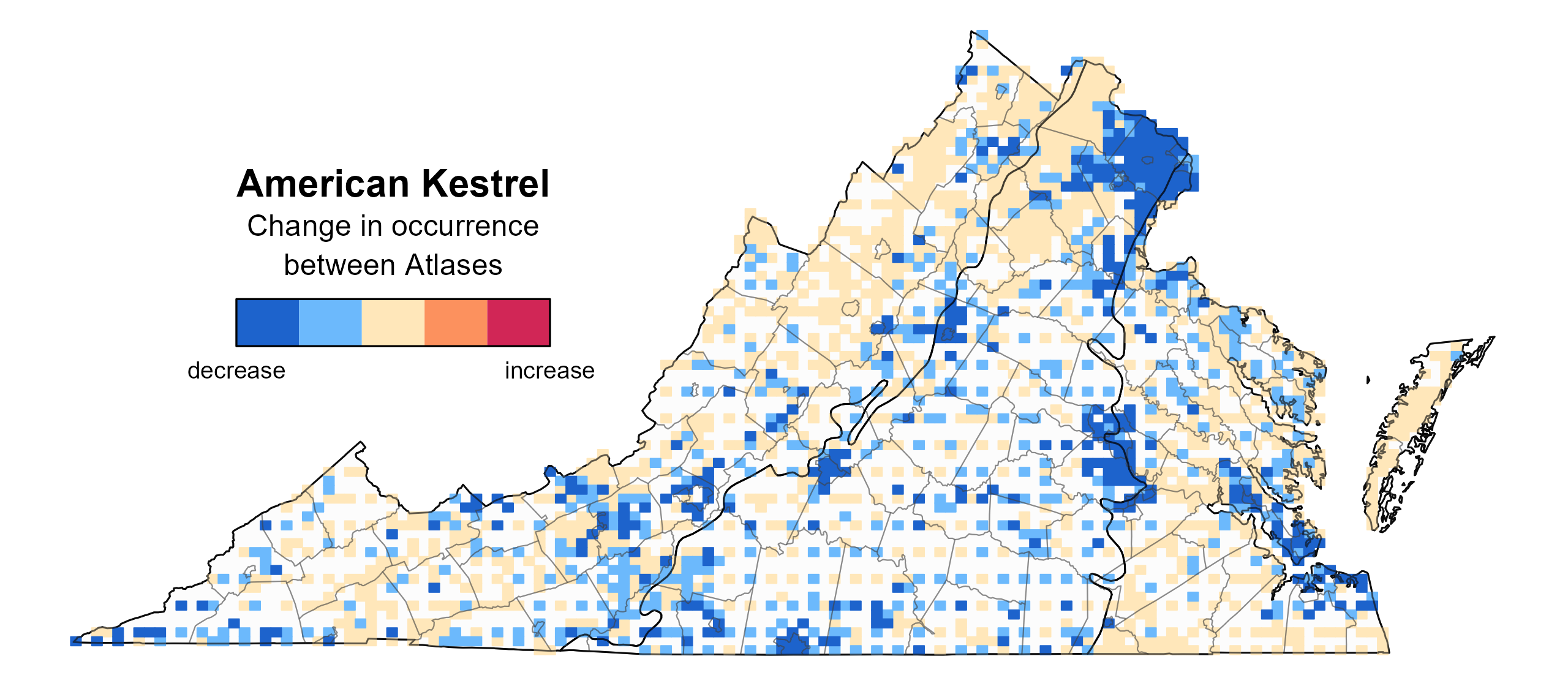

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), American Kestrel’s likelihood of being found in a block declined throughout much of the state (Figure 3). These decreases in predicted occurrence were most pronounced in Northern Virginia, the greater Richmond area, the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area and the Lower Peninsula, and to a lesser extent in an area that includes Giles, Montgomery, and Roanoke Counties in the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 3).

Figure 1: American Kestrel breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: American Kestrel breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not sufficiently surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: American Kestrel change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not sufficiently surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

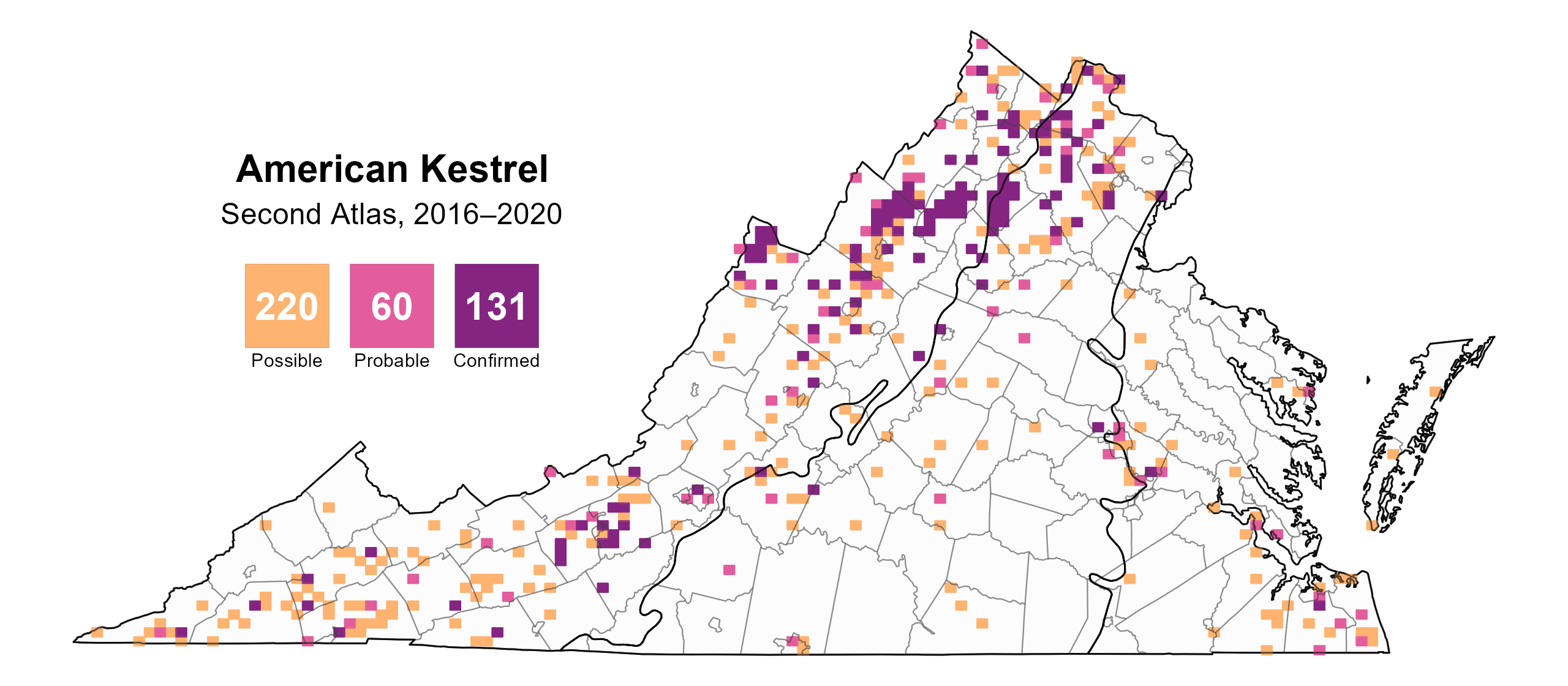

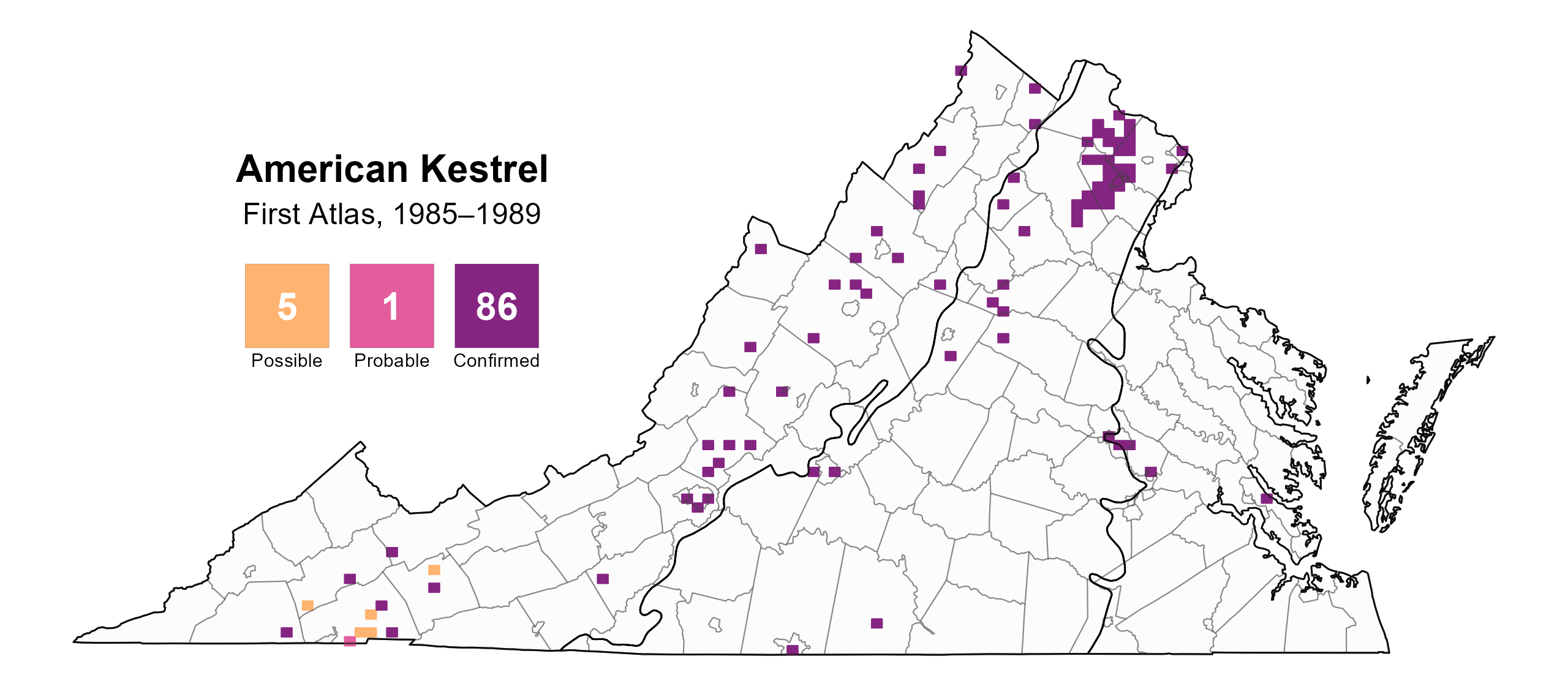

American Kestrels were confirmed breeders in 131 blocks and 34 counties and probable breeders in an additional 16 counties (Figure 4). The number of blocks with breeding observations quadrupled between Atlases, driven in large part by documentation of probable and especially possible breeding. Given declining rates of occurrence between Atlases (see Breeding Distribution) and a negative population trend for the species (see Population Status), the increase in blocks with breeding evidence is likely due to greater survey effort during the Second Atlas (Figures 4 and 5). A substantial increase between Atlases in the number of kestrel nest boxes on the Virginia landscape may also have provided greater opportunities to document kestrel presence.

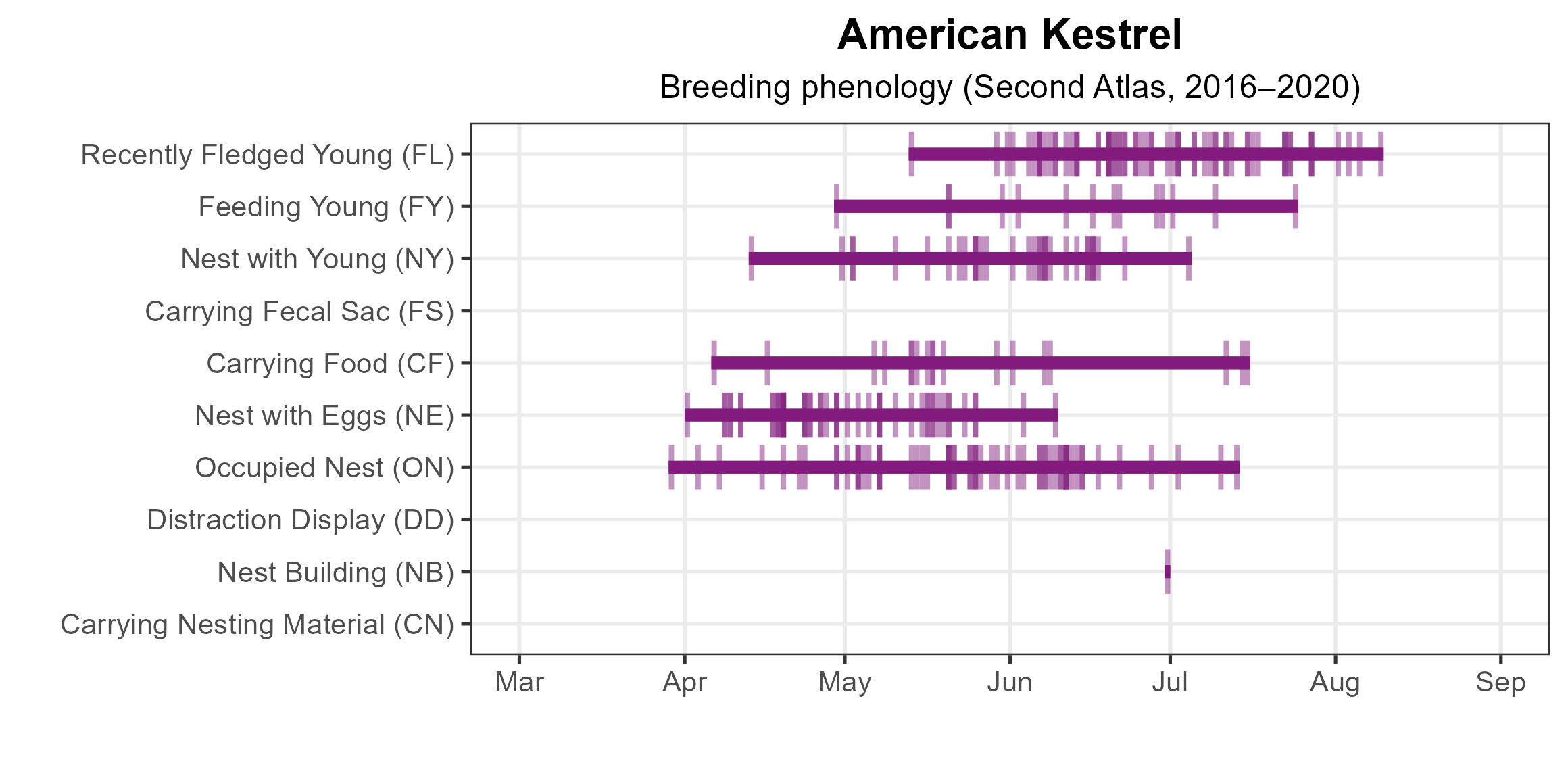

Breeding evidence was recorded primarily through observations of recently fledged young, occupied nests, and nests with young (Figure 6). Occupied nests were observed from March 29 through July 13. Active nests observed after July 1 likely represent second nesting attempts. Fledged young were documented between May 13 and August 9.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: American Kestrel breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: American Kestrel breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category..

Figure 6: American Kestrel phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

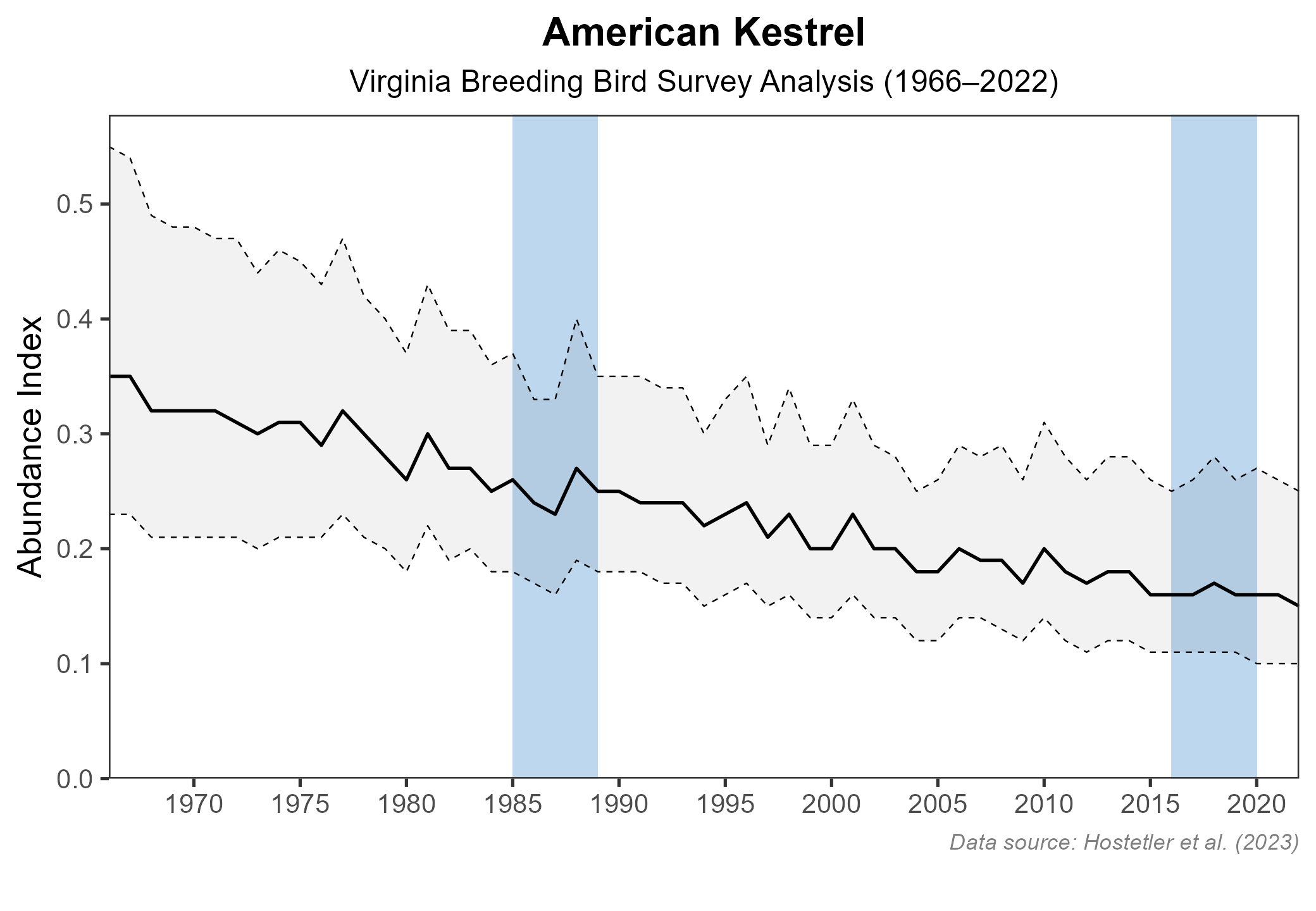

The number of American Kestrel detections in the Atlas point count data were not sufficient to develop an abundance model. North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data showed a significant decrease of 1.47% in its population per year from 1966–2022 in Virginia (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7). Between the First and Second Atlas, BBS data for the Commonwealth showed a nonsignificant decline of 0.92% per year from 1987–2018, indicating a potentially improved outlook for the species.

Figure 7: American Kestrel population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan classifies American Kestrel as a Tier II (Very High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need based on its declining trend and relatively small population (VDWR 2025). Kestrel population declines throughout its North American breeding range may be driven by factors that include the loss and degradation of breeding and wintering habitat and agricultural practices that leave fewer standing trees and subsequently limit nest cavity availability (Smallwood and Bird 2020; Bird and Smallwood 2023).

A convenient and effective conservation strategy to augment the supply of suitable cavities is to place nesting boxes in high-quality habitat where kestrels will thrive. Over recent years, several individuals and organizations have contributed to building and monitoring a network of hundreds of kestrel nest boxes in the northwestern part of the state. Partners include the Virginia Society of Ornithology (VSO), the Clifton Institute, Virginia Working Landscapes, and the Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative (VGBI), as well as self-directed citizen scientists. The VSO’s efforts, which began in 2016, have extended into counties in southwestern Virginia and in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions, resulting in the placement of over 500 nest boxes in 44 counties, including 15 state parks. Kestrel occupancy of nest boxes during the breeding season was 66% of 69 boxes in Highland County in 2021 and as high as 90% of 87 boxes in portions of the Shenandoah Valley between 2008 and 2020 (Morrow and Morrow 2021), suggesting that the boxes are having a positive impact in those areas of the state.

Monitoring is an essential component of nest box programs, but outside of northwestern Virginia and Highland County, it does not take place consistently. Expanding monitoring efforts across the network of boxes would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of the status of American Kestrel in different areas of the state and inform future expansion of nest box deployments. Nest boxes have the added benefit of facilitating research: a GPS transmitter study of adult female kestrels in Rappahannock and Fauquier Counties yielded novel insights on their habitat use away from nesting territories during the breeding season (Kolowski et al. 2023). This and future Virginia-based research will continue to inform conservation and can be coordinated with regional efforts under the nascent American Kestrel Initiative of the Atlantic Flyway Council.

The Wildlife Center of Virginia, VGBI, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s NestWatch program offer guidance for constructing and placing American Kestrel nest boxes. Nest box programs should be complemented by efforts to retain the open habitats favored by the bird. These include promotion of conservation and agricultural land easements, agricultural subsidy programs, and local land use planning efforts to mitigate development impacts (VDWR 2025). Furthermore, other factors potentially contributing to American Kestrel population declines should be investigated. These include increased use of agricultural pesticides that diminish abundance and diversity of insect prey, direct impacts of rodenticides on kestrels, and the effect of a changing climate on the timing of kestrel breeding relative to the availability of its prey (Smallwood and Bird 2020; Bird and Smallwood 2023).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bird, D.M., and J.A. Smallwood (2023). Evidence of continuing downward trends in American Kestrel populations and recommendations for research into causal factors. Journal of Raptor Research 57:131-145. https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-22-35.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Kolowski, J. M., C. Wolfer, M. McDaniels, A. Williams, and J. B. C. Harris (2023). High-resolution GPS tracking of American Kestrels reveals breeding and post-breeding ranging behavior in Northern Virginia, USA. Journal of Raptor Research 57: 544-562. https://doi: 10.3356/JRR-22-106.

Morrow, J., and L. Morrow. 2021. Reproductive parameters of American Kestrels (Falco sparverius) using nest boxes in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia 2008-2020. Maryland Birdlife 70: 7-25.

Smallwood, J. A., and D. M. Bird. 2020.. American Kestrel (Falco sparverius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amekes.01.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.