Introduction

The Pileated Woodpecker is the largest of its family in Virginia and one of our most awe-inspiring birds. The species’ thunderous drumming and trumpeting wuk-wuk-wuk-wuk calls fill the forest as the woodpecker bounds between trunks. With a powerful bill, this woodpecker easily excavates oblong cavities and tears rotting wood (or decking) to shreds in search of insects. Strongly associated with mature hardwood forests with larger trees, in Virginia, Pileated Woodpeckers prefer oak-hickory forests, mature stands with dense vegetation near the ground, and high basal area (Conner 1981). Large-diameter trees are crucial for hosting the species’ large nest cavities, which are typically excavated in dead or hollow portions of the main trunk (Conner et al. 1975). As a primary cavity excavator, Pileated Woodpeckers provide roosts and nests for many other species, such as Eastern Screech-Owls (Megascops asio) and Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa).

Breeding Distribution

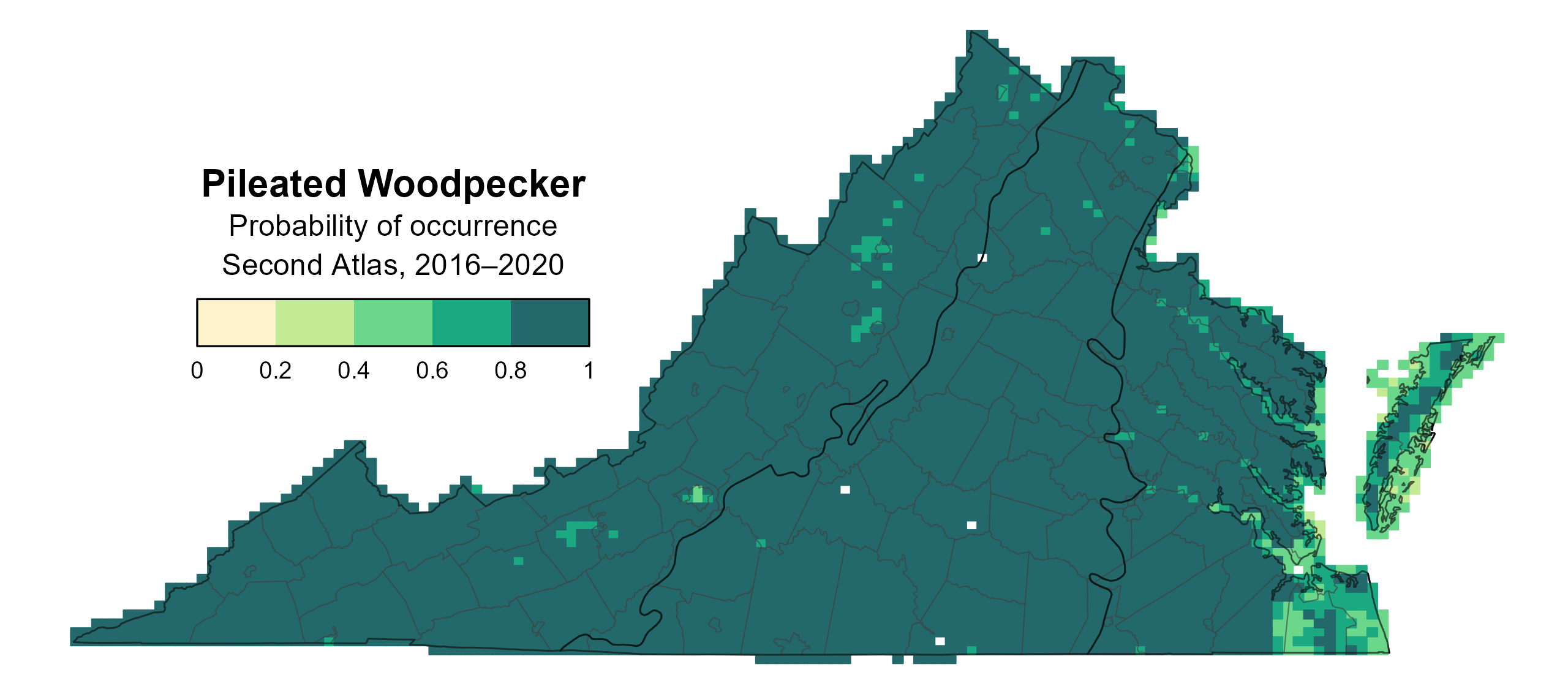

Pileated Woodpeckers, generally sedentary throughout the year, inhabit all regions of the state. However, they may be less likely to occur in the Shenandoah Valley and other areas of the state where there is less forest and tree cover (Figure 1). The species is also less likely to occur in the Coastal Plain region along major river corridors, in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area, and on the Eastern Shore. The species’ likelihood of occurring increases as the proportion of forest cover in a block increases.

Distribution during the First Atlas and the ensuing change between Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Account). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Pileated Woodpecker breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

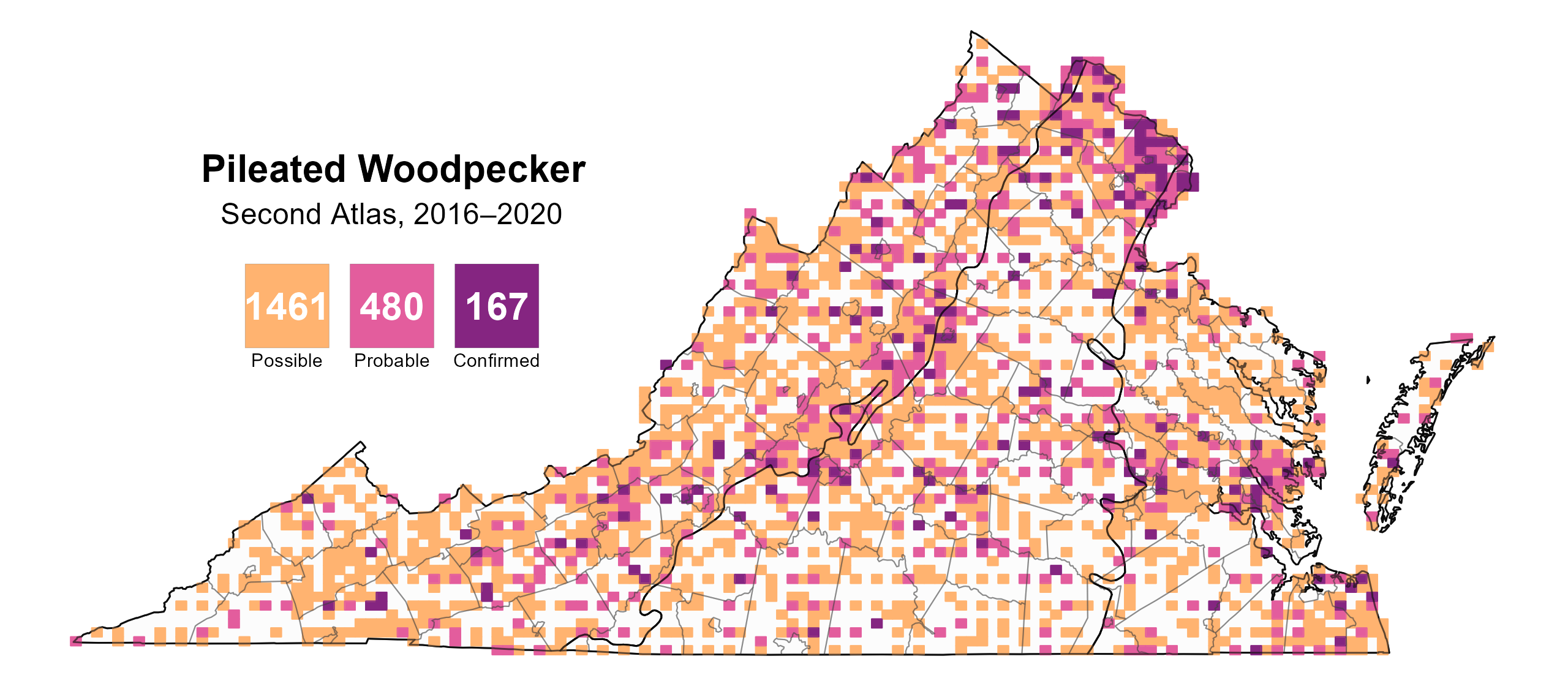

Breeding Evidence

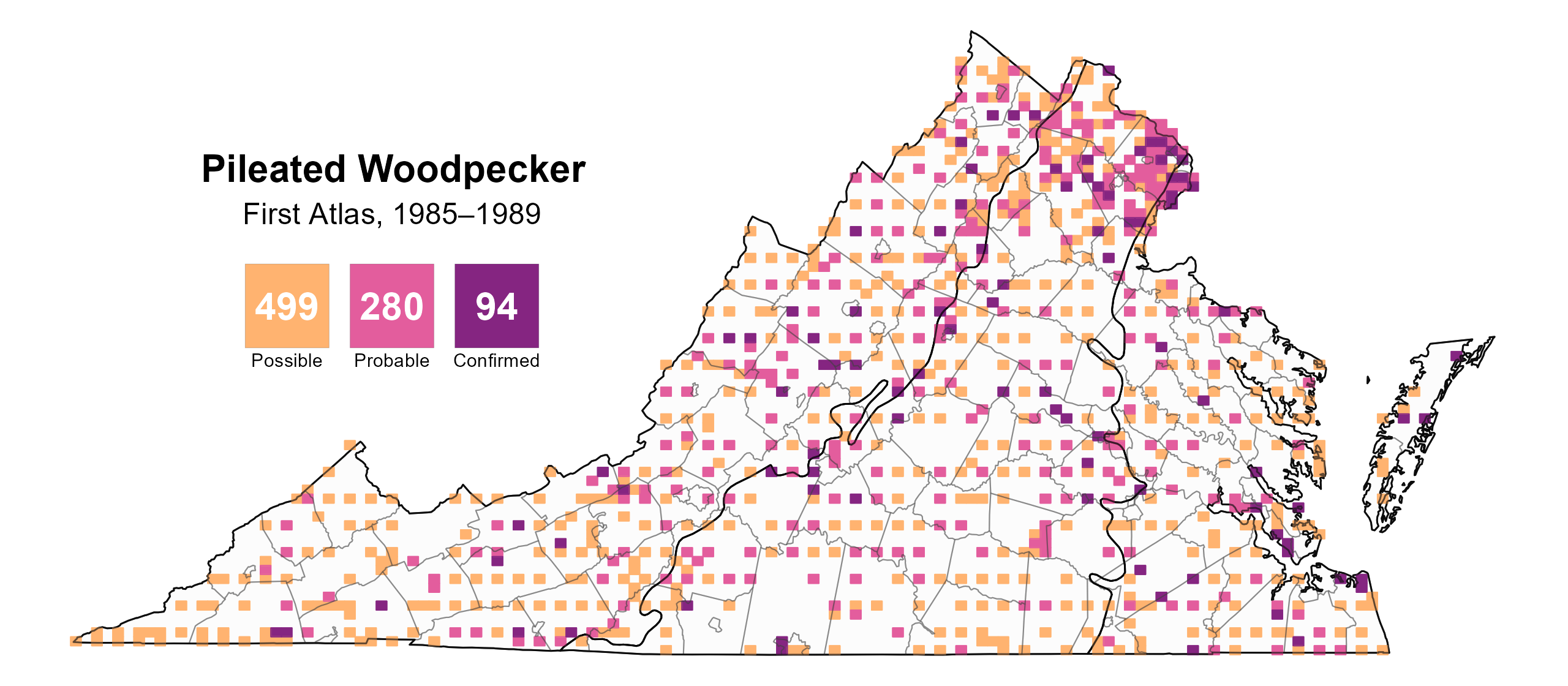

Pileated Woodpeckers were confirmed breeders in 167 blocks and 71 counties and probable breeders in an additional 38 counties (Figure 2). The species was considered a possible breeder or merely observed in an even broader distribution of blocks and counties. For example, Pileated Woodpeckers were only confirmed in one block on the Eastern Shore, but they were possible or probable in an additional 25 blocks. Despite their conspicuous appearance, they have large home ranges and are typically at their most vocal prior to the nesting season (Bull and Jackson 2020); thus, they can be difficult to track to their nests for confirmation. During the First Atlas, volunteers also observed Pileated Woodpeckers breeding in all regions of the state (Figure 3).

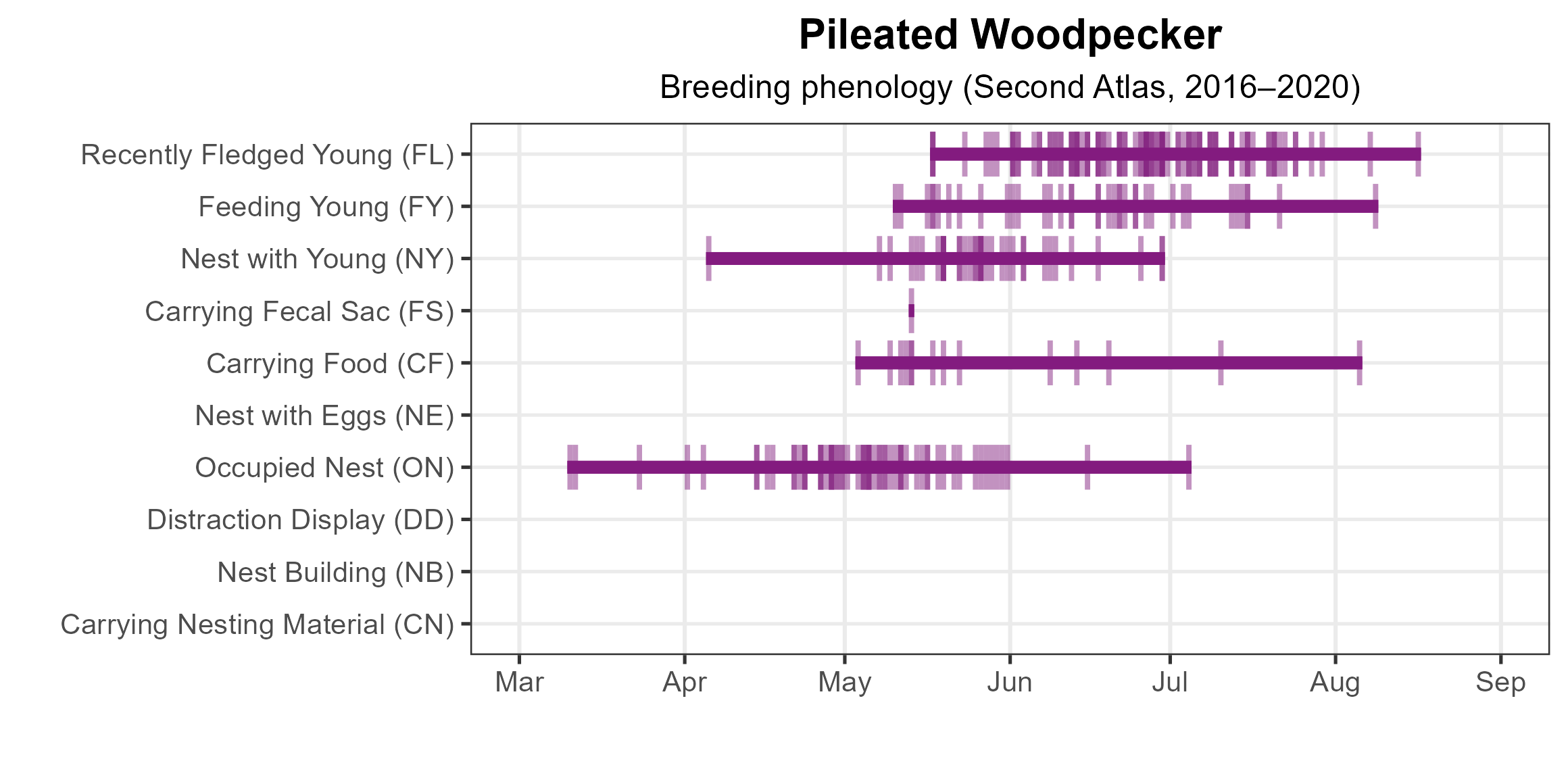

Pileated Woodpeckers began occupying nests on March 10, and nests with young were observed starting on April 5 (Figure 4). Fledglings appeared starting on May 17 and continued through August 16. Given their habit of nesting in cavities high up in large, decaying trees, this is not a species whose eggs are likely to be observed; thus, zero nests with eggs were found. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Pileated Woodpecker, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Pileated Woodpecker breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Pileated Woodpecker breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Pileated Woodpecker phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

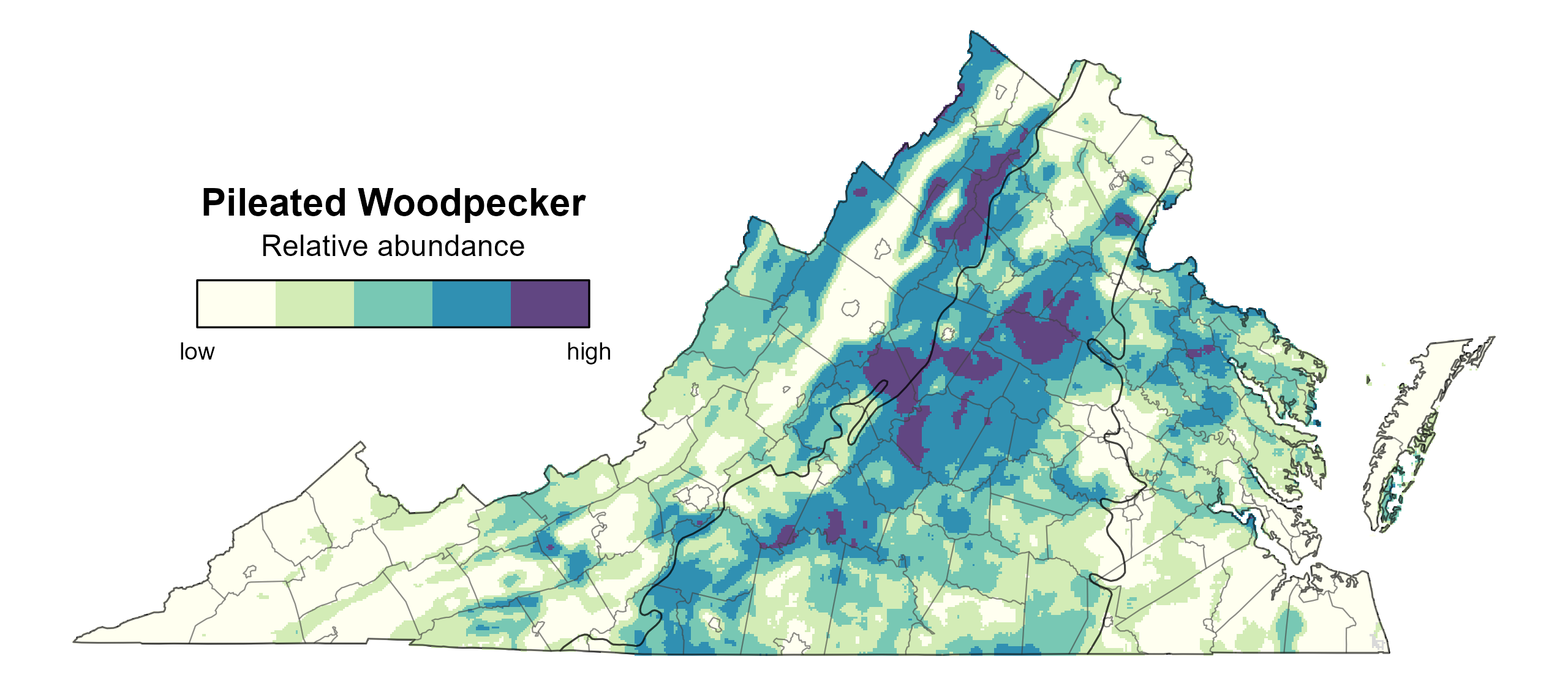

Pileated Woodpecker relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the Blue Ridge Mountains and central Piedmont (Figure 5). They were relatively abundant in forested areas throughout most of the state, but they were predicted to be less abundant in the Shenandoah Valley, urban areas like Northern Virginia and Richmond, and the Eastern Shore.

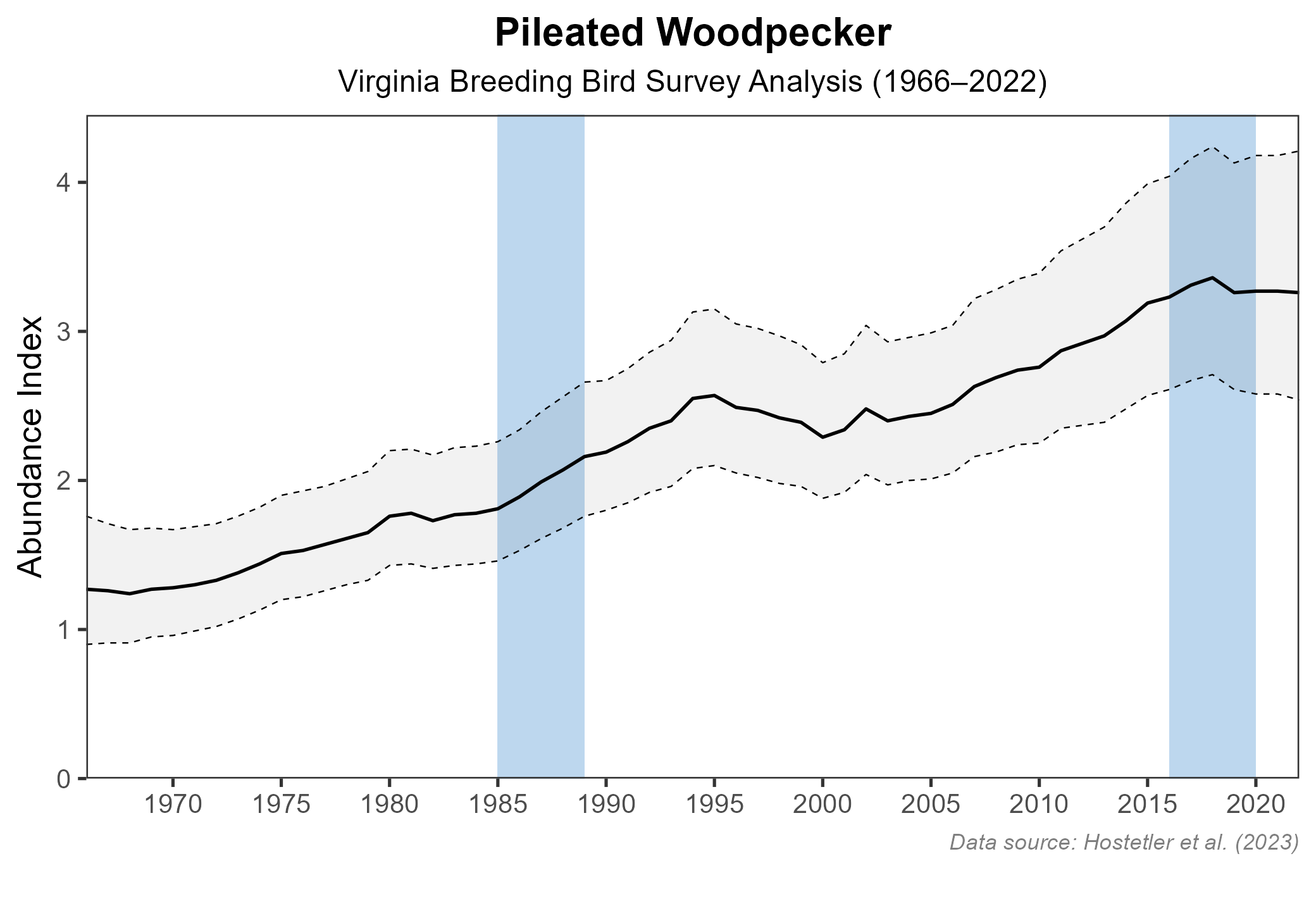

The total estimated Pileated Woodpecker population in the state is approximately 357,000 individuals (with a range between 181,000 and 707,000). However, the abundance model was considered weak, meaning its ability to explain observed variation was low (see Analytical Methods), hence the wide range of the estimate. Pileated Woodpecker populations are increasing in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed a significant increase of 1.75% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6). Between Atlases, BBS data showed the same trend, with a significant increase of 1.7% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Pileated Woodpecker relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Pileated Woodpecker population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Pileated Woodpeckers were scarce in eastern North America during the period of intense land clearing for agriculture and timber harvest. However, since the early 1900s, the species has steadily increased as forests have regrown and matured. More recently, population increases since 1950 may be partially attributable to continuing forest maturation and increasing food and cavity opportunities presented by tree mortality due to introduced insects and pathogens such as Dutch Elm Disease (Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and Ophiostoma ulmi) (Bull and Jackson 2020). Pileated Woodpecker populations are secure in Virginia, and they are not a species of concern. Like many woodpeckers, this species benefits when landowners leave large trees for nesting and stumps and fallen logs for foraging.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bull, E. L., and J. A. Jackson (2020). Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.pilwoo.01.

Conner, R. N. (1981). Seasonal changes in woodpecker foraging patterns. The Auk 98:562–70.

Conner, R. N., R. G. Hooper, H. S. Crawford, and H. S. Mosby (1975). Woodpecker nesting habitat in cut and uncut woodlands in Virginia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 39:144–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3800477.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.