Introduction

The White-eyed Vireo is an irascible bird that pops out of dense, regenerating shrub thickets, commonly providing an intense, white-eyed staring contest alongside its snappy calls. Its bold behavior led early naturalists to describe it as “fearless,” “irritable,” “spritely,” “snappish,” and “pompous” (Hopp 2022). John James Audubon even called it a “petulant, infantile, and original freak” (Audubon 1870).

As short-distance migrants, White-eyed Vireos typically return to their habitats throughout Virginia in early spring. The species inhabits a variety of habitat types, including forest edges and secondary deciduous scrub. It is commonly found in areas with late successional habitats that occur after pasture abandonment, clear-cuts, mining, or other disturbances (Hopp 2022). These habitats are all diverse in species and structure, with shrubs, brambles, saplings, undergrowth, and taller trees intermixed. White-eyed Vireos are unique among their family because they incorporate vocal mimicry into their songs, having been documented imitating the call notes of more than 30 different species (Adkisson and Conner 1978).

Breeding Distribution

White-eyed Vireos are found in all regions of the state, although they are much less likely to occur in the southern Shenandoah Valley and in the Hampton Roads area (Figure 1). The species is also unlikely to occur in the urban surroundings of Richmond or in the vicinity of Bath or Highland County. White-eyed Vireos are scarce in the Appalachian Mountains compared to in the rest of their range. When they occur in the Mountains and Valleys region, they typically are found in the lowlands, although they have been documented at higher elevations (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; Hopp 1985). They are also more likely to occur in southwestern Virginia, particularly in Lee, Russell, and Wise Counties, than in the rest of this region.

Given their habitat preferences for shrubby marsh edges and upland edge habitat in the Coastal Plain region (Smith and Watts 2017), the likelihood of White-eyed Vireos occurring in a block increases in areas with a greater proportion of shrubland and grassland habitats and a greater number of habitat types. In contrast, they are less likely to occur in areas with non-scrub land cover and areas with increasing proportions of forested, agricultural, or developed land cover. Their occurrence is also positively associated with the number of forest patches but negatively associated with the size of the largest forest patch, indicating that a fragmented landscape with many small patches and edge habitat is most likely to contain the species.

White-eyed Vireo’s distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its occurrence during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: White-eyed Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

White-eyed Vireos were confirmed breeders in 199 blocks and 74 counties and probable breeders in an additional 24 counties (Figure 2). Confirmations were evenly distributed across the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions but were sparse in the Mountains and Valleys region, particularly away from the Blue Ridge and Cumberland mountains. Breeding was also observed in all regions of the state during the First Atlas (Figure 3).

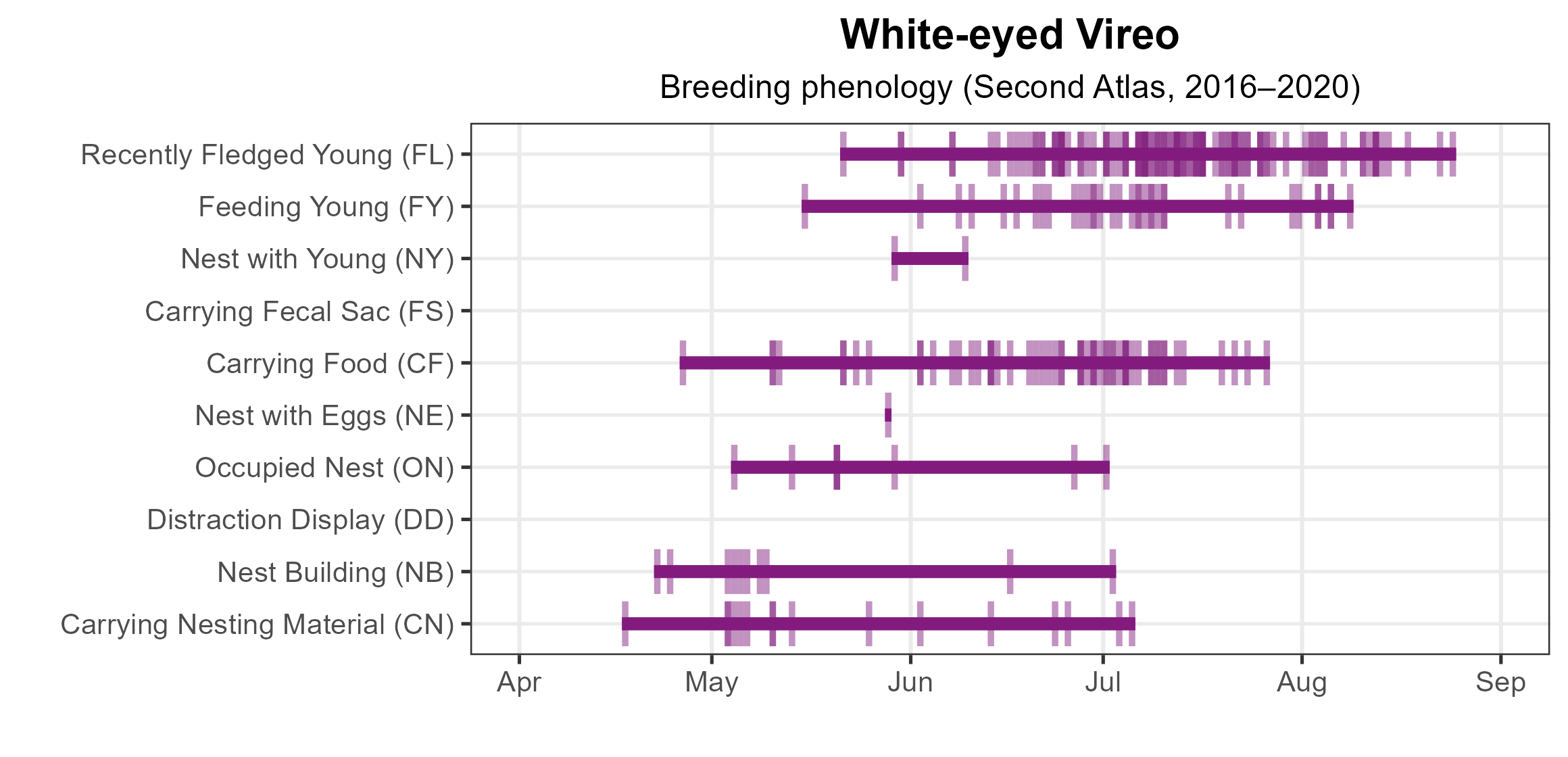

Breeding was confirmed from April 17 (carrying nesting material) to August 24 (recently fledged young) (Figure 4). Observers documented White-eyed Vireos performing nearly every type of breeding activity, although most confirmations came from observations of recently fledged young, adults carrying food, and adults feeding young. Only one nest with eggs was observed. For more general information on the breeding habits of the White-eyed Vireo, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: White-eyed Vireo breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: White-eyed Vireo breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: White-eyed Vireo phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

White-eyed Vireos are widespread but localized in appropriate habitat. Their relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the southeastern Piedmont and southern Coastal Plain regions (Figure 5). The species was mostly absent or at extremely low abundance levels in urban areas and in the northern and parts of the southern Mountains and Valleys region.

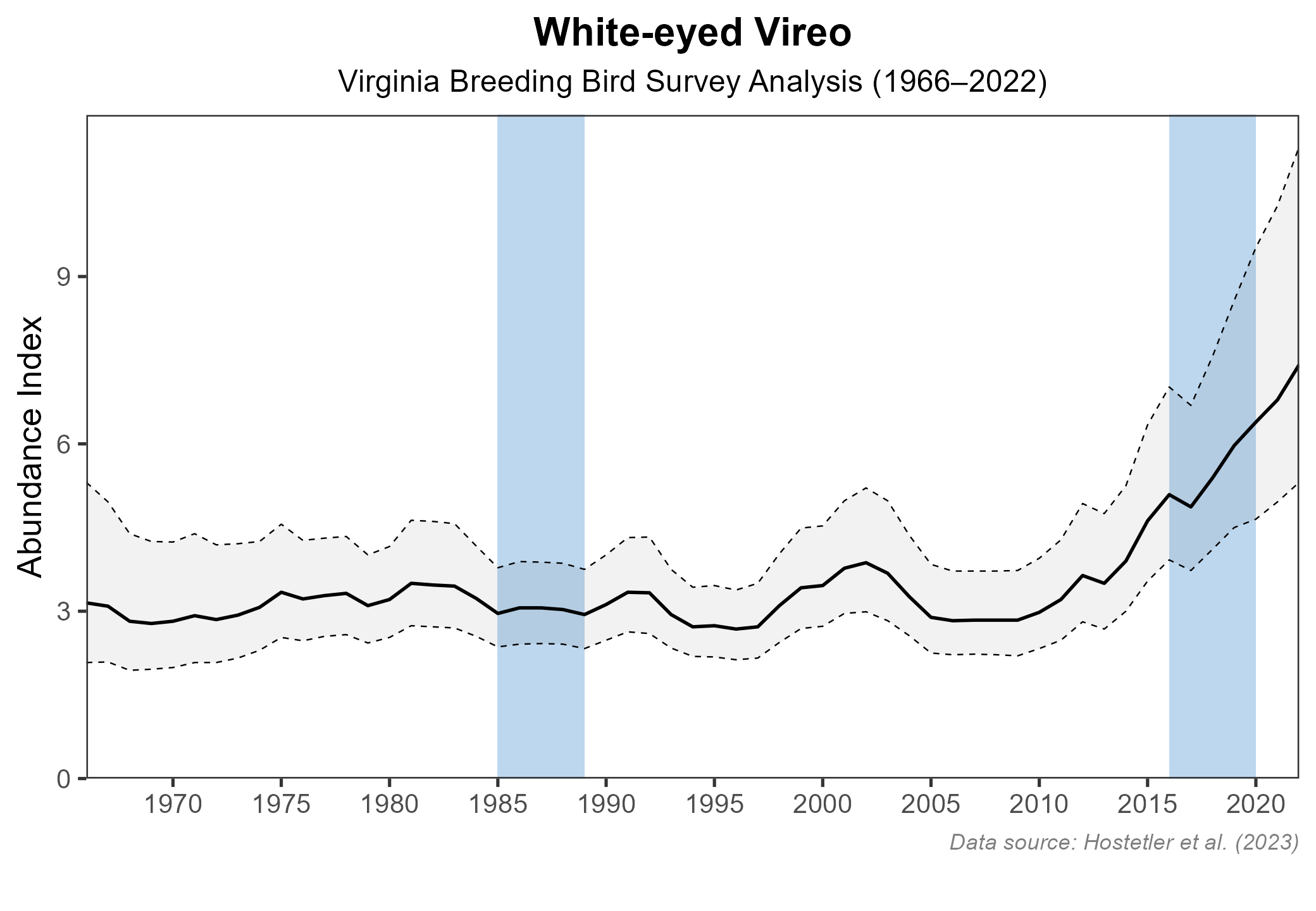

The total estimated White-eyed Vireo population in the state is approximately 481,000 individuals (with a range between 353,000 and 663,000). Population trends for the species appear stable to increasing in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) population trend showed a significant increase of 1.55% per year from 1966–2022 in the state (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend for Virginia showed a similar significant increase of 1.85% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: White-eyed Vireo relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: White-eyed Vireo population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because White-eyed populations are stable to increasing, this species is not the focus of any conservation efforts in Virginia. However, any efforts to conserve and restore shrubland habitats will also benefit White-eyed Vireos.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Adkisson, C. S., and R. N. Conner (1978). Interspecific vocal imitation in White-eyed Vireos. The Auk 95:602–606. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4085175.

Audubon, J. J. (1870). The Birds of America. Vol. 4. New York, NY, USA.

Hopp, S. L. (1985). High altitude records of White-eyed Vireos. The Raven 56:40–41.

Hopp, S. L. (2022). White-eyed Vireo (Vireo griseus), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.whevir.02.

Hopp, S. L., A. Kirby, and C. A. Boone (1995). White-eyed Vireo (Vireo griseus). In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. Gill, Editors). Academy of Natural Sciences and American Ornithologist’s Union Philadelphia, PA. and Washington, DC,USA.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Jirinec, V., D. A Cristol, and M. Leu (2017). Songbird community varies with deer use in a fragmented landscape. Landscape and Urban Planning 161:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.01.003.

Penhollow, M. E., and F. Stauffer (2000). Large-scale habitat relationships of neotropical migratory birds in Virginia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 64:362–373. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803234.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Smith, F., and B. Watts (2017). Frequency and distribution of birds within forested wetlands – breeding and wintering seasons. CCBTR-17-07. Center for Conservation Biology, College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA.