Introduction

While some might view the carrion-eating Turkey Vulture with disdain, a deeper look reveals many fascinating adaptions. Turkey Vultures have excellent olfaction, having the ability to detect just a few parts per trillion of the chemical compounds associated with rotting flesh (Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2019). Interestingly, when captured or approached, the species will vomit or act dead to defend itself (Kirk and Mossman 2020). In addition, as a means of staying clean and preventing infections, it has evolved a featherless head to safely feed on the bacteria-filled flesh of dead animals (Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2019).

Breeding Distribution

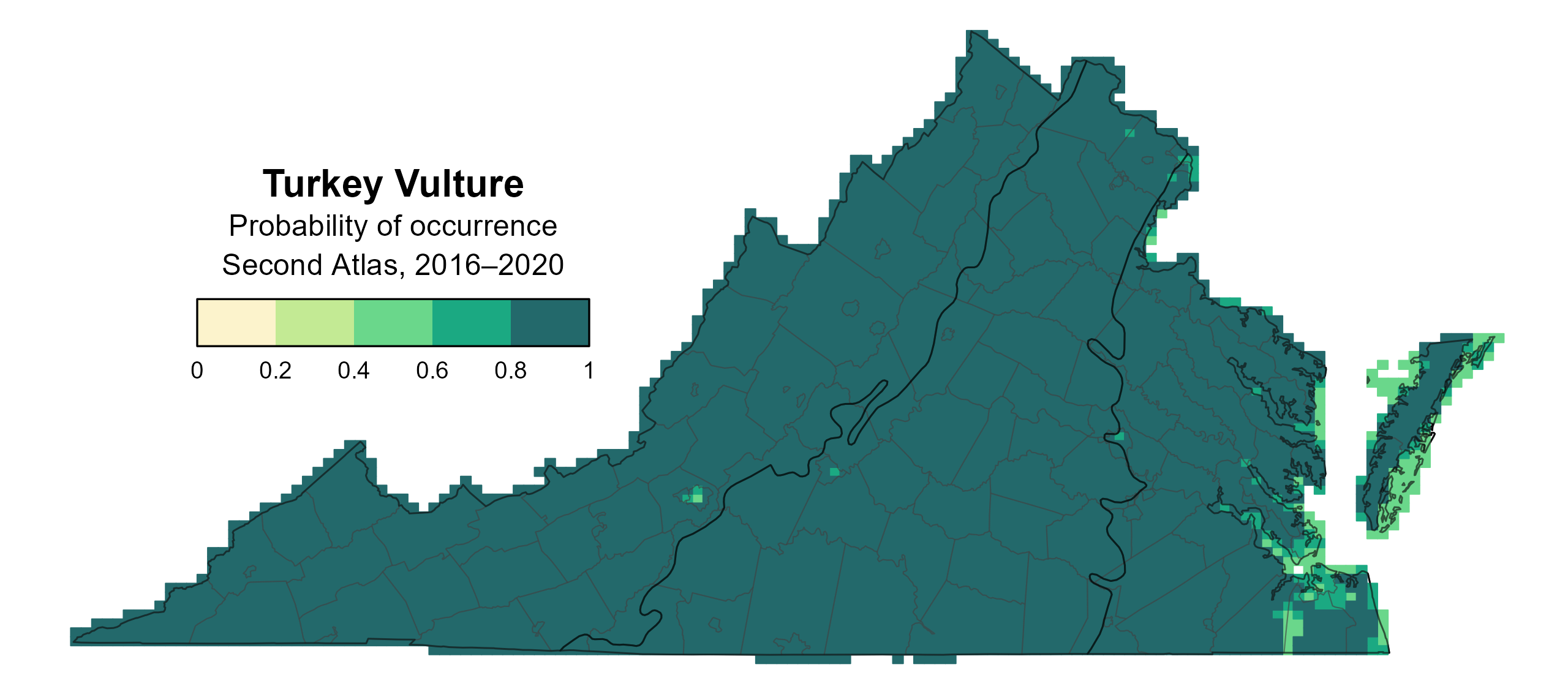

Turkey Vultures are ubiquitous throughout Virginia, with a high likelihood of occurring throughout the state (Figure 1). Few (if any) other species match the Turkey Vulture’s unbroken distribution within Virginia. The species is only lacking in areas of the Coastal Plain region and the Eastern Shore where year-round inundation of water prevents the establishment of nesting and foraging habitat.

Because of model limitations, its distribution during the First Atlas and the change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on the Turkey Vulture’s occurrence during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Turkey Vulture breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

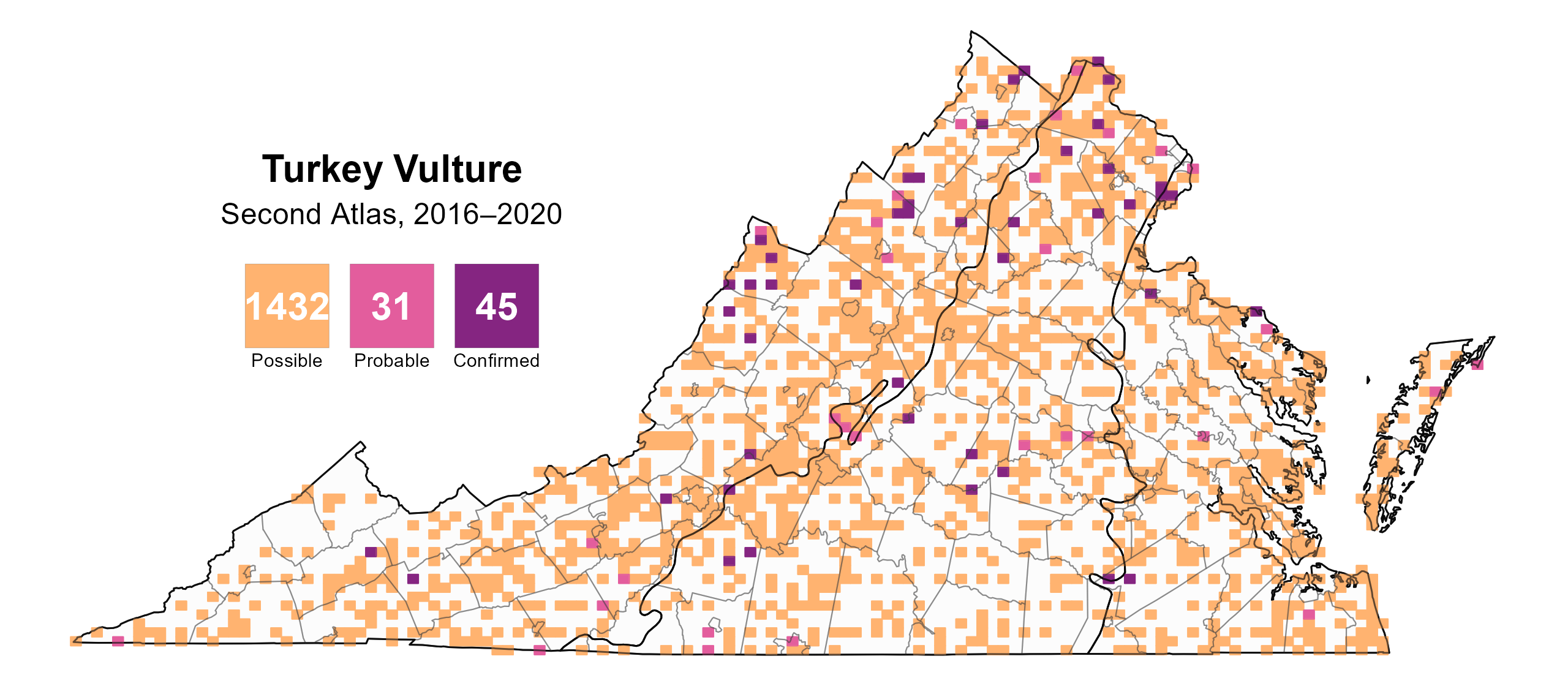

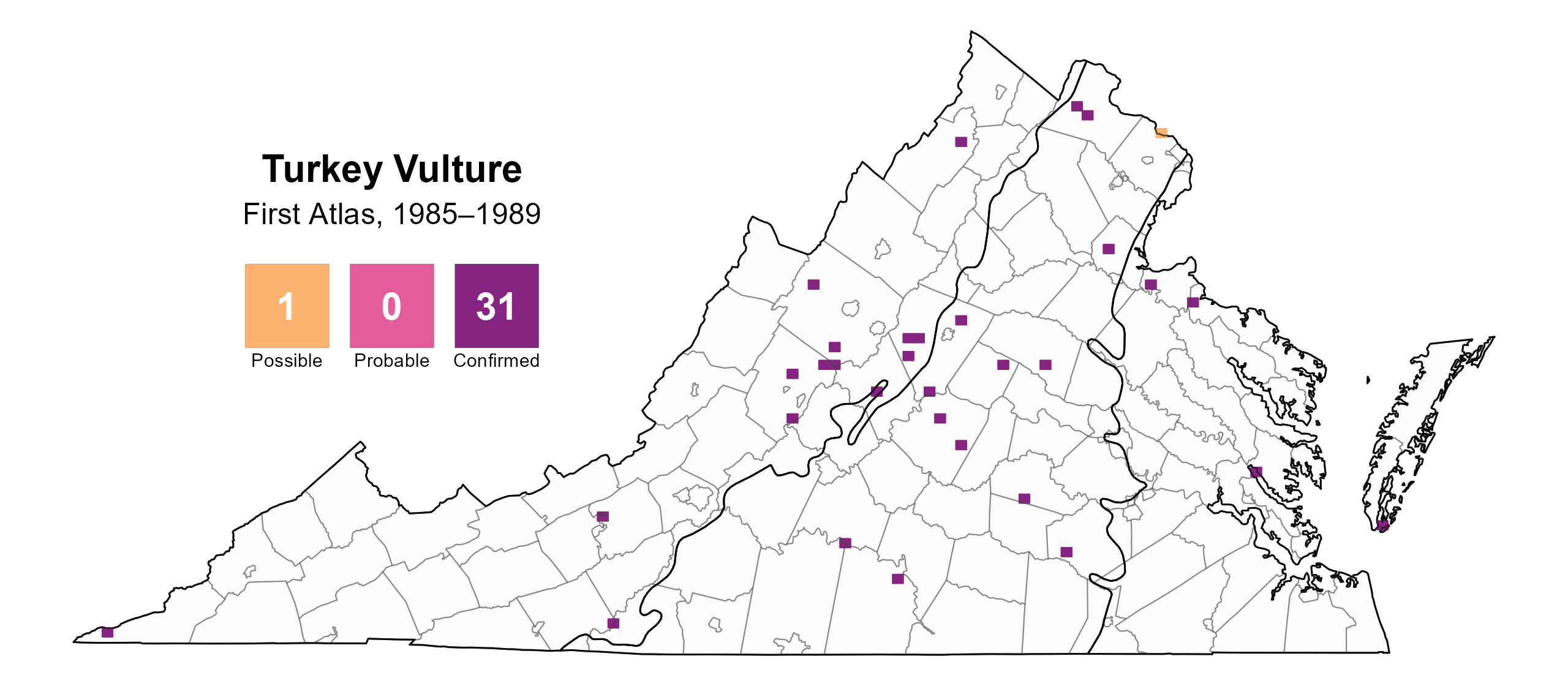

Turkey Vultures were confirmed breeders in 45 blocks and 25 counties and found to be probable breeders in an additional 13 counties throughout the entire state (Figure 2). However, possible breeders were observed throughout the state. Additionally, many more breeding observations were recorded during the Second Atlas than during the First Atlas; however, this may be largely due to increased survey effort (Figures 2 and 3).

The earliest confirmed breeding behavior was documented in early April when a nest with eggs was recorded (Figure 4). The most frequently recorded breeding confirmations were recently fledged young (May 16 – August 4). Occupied nests were observed May 15 – July 28, and nests with young were observed June 11 – June 26. For more information on the breeding phenology of this species, please see All About Birds.

Figure 2: Turkey Vulture breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Turkey Vulture breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Turkey Vulture phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

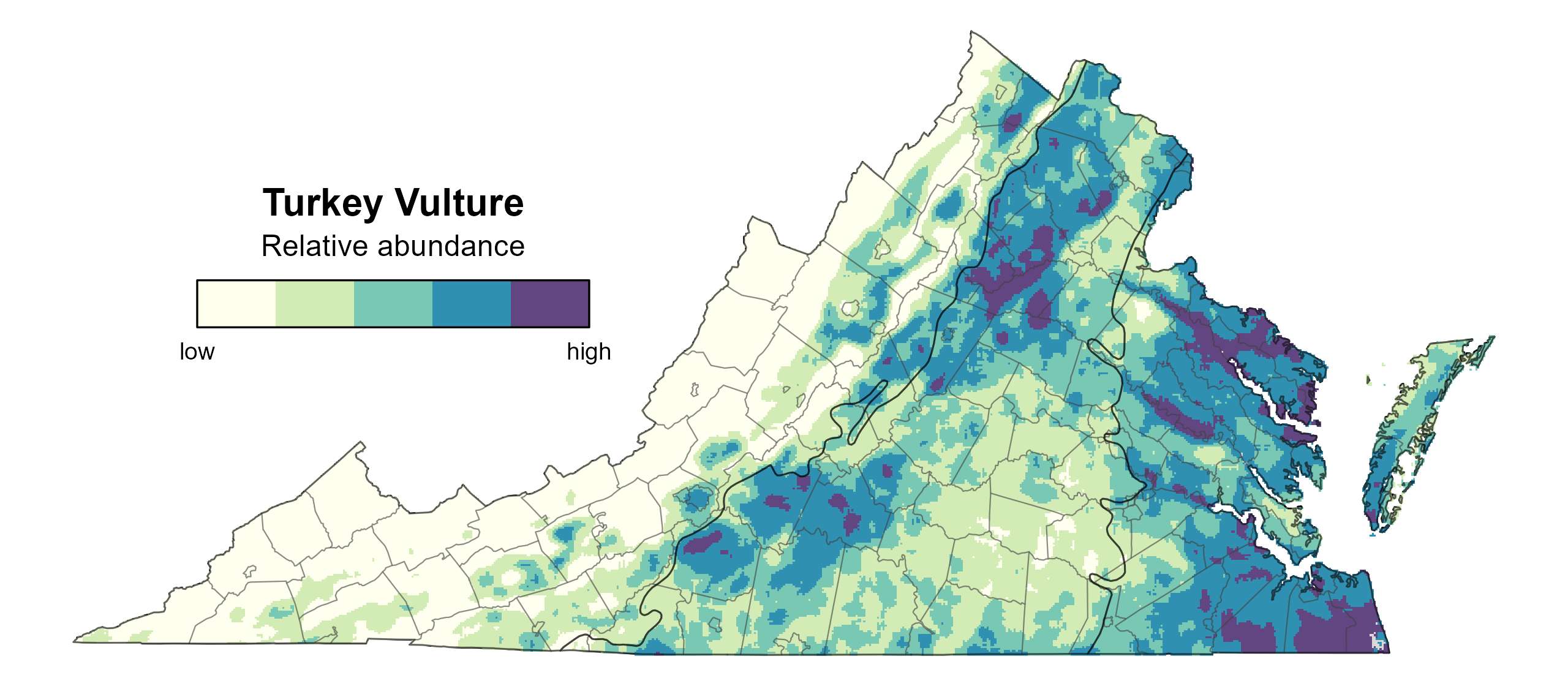

Turkey Vulture relative abundance was estimated to be highest in portions of the western Piedmont and the Coastal Plain region, especially in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area and parts of the Northern and Middle Peninsulas (Figure 5).

The total estimated Turkey Vulture population in the state is 254,000 individuals (with a range between 127,000 and 512,000). Based on the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trend for Virginia, the Turkey Vulture population increased by a significant 2.02% annually from 1966–2022, and between Atlas periods, it increased at a similar significant rate of 2.56% per year from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6).

Figure 5: Turkey Vulture relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Turkey Vulture population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

While Turkey Vultures are not of high conservation concern, they are considered a “keystone species,” meaning their removal from ecosystems would cause cascading biological effects, impacting other organisms. For example, without Turkey Vultures, large numbers of animal carcasses could accumulate, poisoning surface water and spreading diseases to other wildlife and humans (Kirk and Mossman 2020).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2019. All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Turkey_Vulture/.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Kirk, D. A. and M. J. Mossman (2020). Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.turvul.01.