Introduction

If you have spent time watching flocks of swallows in Virginia, then you have likely seen Northern Rough-winged Swallows but might not have known it. These inconspicuous, brown swallows forage over water along with other swallow species and are often overlooked. Their name comes from tiny hooks on the leading edge of their primary feathers. Northern Rough-winged Swallows nest in open areas along waterways, where they use burrows created by other species, such as Bank Swallows (Riparia riparia) or Belted Kingfishers (Megaceryle alcyon) (De Jong 2020). They are also known to occur in habitats created by human activity and on a variety of artificial structures.

Breeding Distribution

Due to model limitations, a distribution model could not be developed for the Northern Rough-winged Swallow (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its breeding distribution, please see the Breeding Evidence Section.

Breeding Evidence

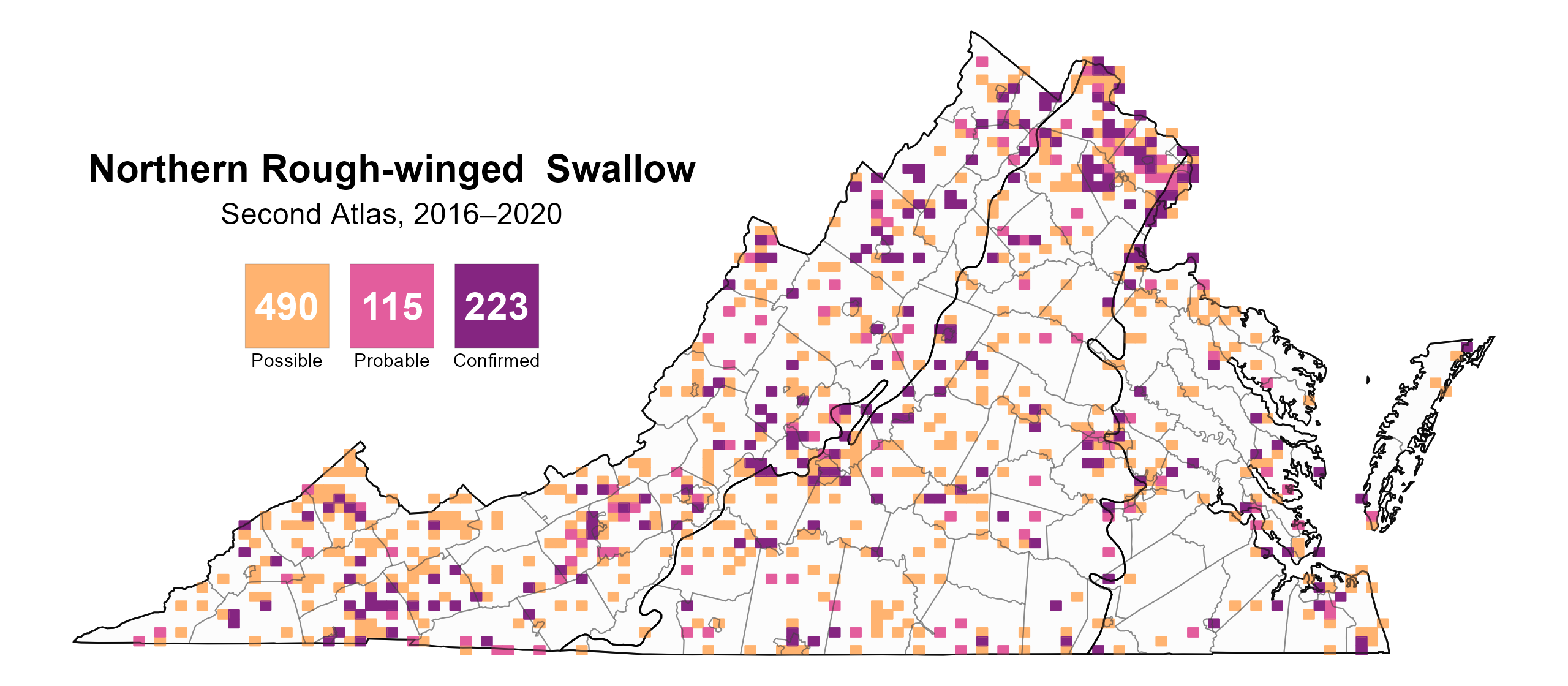

Northern Rough-winged Swallows were confirmed breeders in 223 blocks and 92 counties and found to be probable breeders in an additional 13 counties distributed across all three ecoregions (Figure 1). The distribution of breeding confirmations was similar between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2). Despite its declining population trend (see Population Status section), the swallow was documented in more blocks during the Second Atlas than the First. Although this is likely a result of greater survey effort during the Second Atlas, it suggests that its overall distribution has not been affected by its shrinking population.

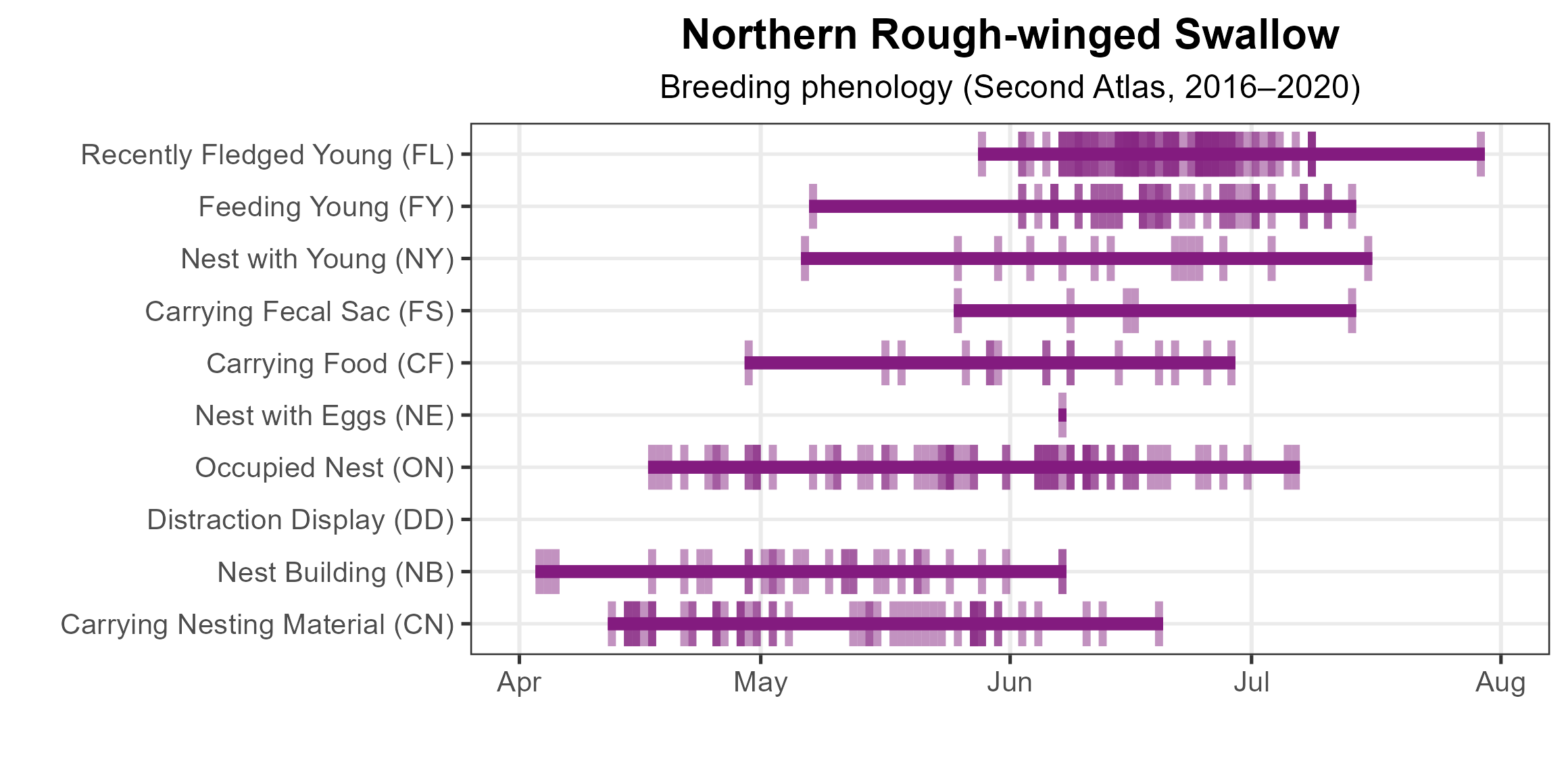

Nest building was observed as early as April 3. Breeding was confirmed primarily through observations of adults carrying nesting material (April 12 – June 19), occupied nests Apr 17 – July 6), and recently fledged young (May 28 – July 29) (Figure 3).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Northern Rough-winged Swallow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Northern Rough-winged Swallow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Northern Rough-winged Swallow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

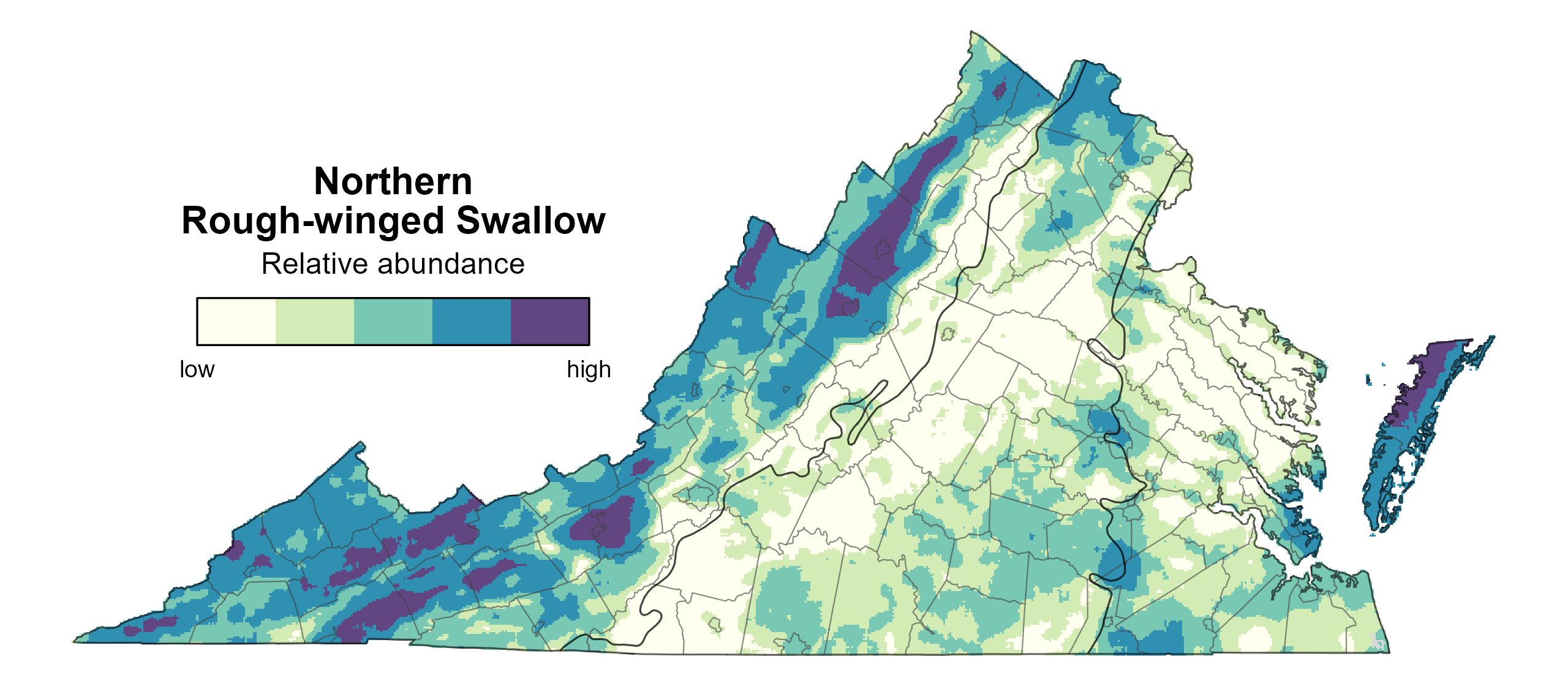

Northern Rough-winged Swallow relative abundance was estimated to be moderate to low in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions (Figure 4). The exceptions were the northern Piedmont area and the Eastern Shore, where the species was predicted to have some of the highest abundances in the state, despite relatively few detections during the Atlas point count surveys (Figure 4). The species was predicted to be more abundant in the Mountains and Valleys region, especially the Shenandoah Valley, southern Blue Ridge Mountains, and areas of southwestern Virginia.

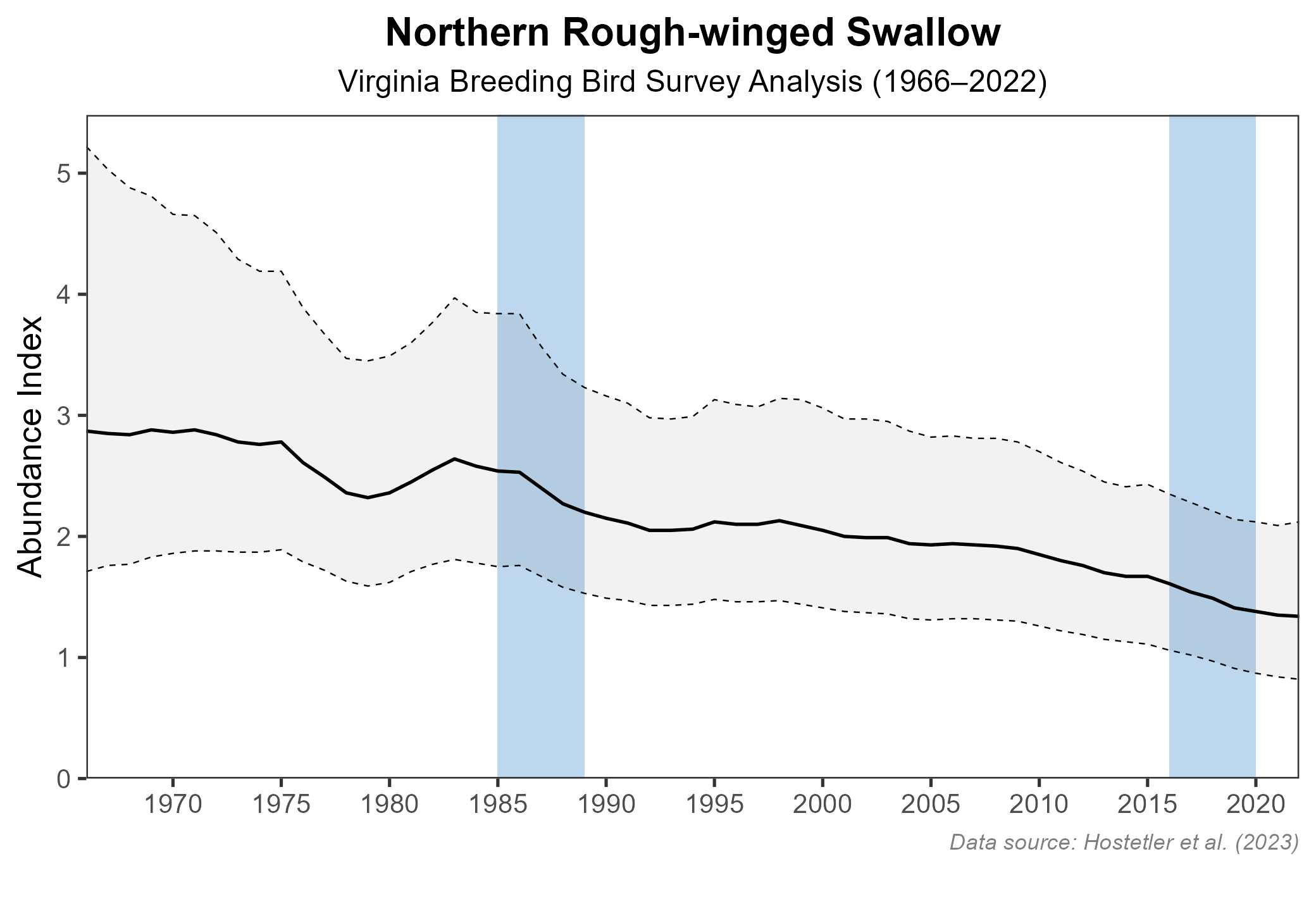

The total estimated Northern Rough-winged Swallow population in the state is approximately 195,000 individuals (with a range between 35,000 and 1,082,000). Based on the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), the Northern Rough-winged Swallow population declined by a significant rate of 1.36% per year from 1966–2022 in Virginia, and between Atlas periods (1987–2018), it decreased by a significant 1.53% per year (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5).

Figure 4: Northern Rough-winged Swallow relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 5: Northern Rough-winged Swallow population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

As a result of its ongoing decline within the Commonwealth, the Northern Rough-winged Swallow is designated as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need Tier III (High Conservation Need) in the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). Although the species is predicted to reach its highest densities in the Mountains and Valleys region, other areas of the state may be significant for Northern Rough-winged Swallow but were inaccessible to the road-based point count surveys used to build the abundance models. Among these areas are vertical banks, bluffs, and cliffs along rivers within the Coastal Plain. In the mid-1990s, a Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) survey of exposed tributary banks in the Chesapeake Bay found Northern Rough-winged Swallows to be well-distributed along the major rivers, including the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James, with over 450 breeding pairs, but a more recent survey of this area has not been conducted (Bryan Watts, unpublished data). A 2022 CCB survey found the species also nests in quarries (Bryan Watts, unpublished data). Given the relatively high density of different types of quarries across the state, there is potential for high rates of use by Northern Rough-winged Swallows. Surveys of a sample of quarries across ecoregions would shed further light on the frequency of their use by the species.

Although Northern Rough-winged Swallows can excavate their own nests, they are commonly found nesting in burrows created by other species (De Jong 2020). It is unclear whether this creates a dependency such that the supply of available burrows may limit the swallow’s ability to nest in more natural settings. At the same time, the species is widely documented as nesting within holes, cracks, and crevices in artificial structures (De Jong 2020). In fact, Atlas volunteers observed nesting under bridges, in drainage pipes, and in exhaust pipes of generators, boats, trucks, and buses. The swallow’s flexibility in choosing where to nest provides it with an ample supply of nest sites.

Unlike the Bank Swallow, which nests in colonies that can number between dozens and hundreds of pairs (Garrison and Turner 2020), the Northern Rough-winged Swallow nests alone or in small groups of 2–25 pairs (De Jong 2020). Along tributaries to the Chesapeake Bay, burrow densities at any given site tend to be low (Bryan Watts, unpublished data), making it more difficult to designate and protect discrete sites of high conservation significance but providing the swallow with more resiliency in the face of ever-changing conditions along river corridors, such as erosion, erosion control efforts, and shoreline development. This, as well as the species’ adaptability to nesting on artificial structures and in habitats altered or disturbed by humans, may provide it with some level of resilience. Nesting success and productivity should be researched in these artificial situations to evaluate whether they contribute to the sustainability of the population as artificial nest burrows have been used successfully at bank and cliff sites (De Jong 2020). Thus, further research is needed to assess their effectiveness as a conservation tool.

Additionally, the Northern Rough-winged Swallow winters along the Gulf Coast and in Central America. Understanding where Virginia’s birds migrate would help evaluate whether conditions on their nonbreeding grounds are contributing to their declines.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

De Jong, M. J. (2020). Northern Rough-winged Swallow (Stelgidopteryx serripennis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.nrwswa.01.

Garrison, B. A., and A. Turner (2020). Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.banswa.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.