Introduction

Great Horned Owls hold several distinctions in Virginia. They are our largest breeding owl and are among the earliest nesters, with occupied nests observed as early as January. Great Horned Owls prey on mammals as large as raccoons (Procyon lotor) and birds as large as geese and even Great Blue Herons (Ardea herodias). They are also the only avian predator that regularly eats skunks (Mephitis mephitis). Highly opportunistic, they also harvest smaller prey such as mice (Mus musculus) and voles (Microtus arvalis), snakes and lizards, songbirds, and even insects. Like most owls, they do not construct their own nests but often use platform-type nests of other species, commonly those of Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) or American Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos). They sometimes nest in tree cavities or even directly on the ground (Artuso et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

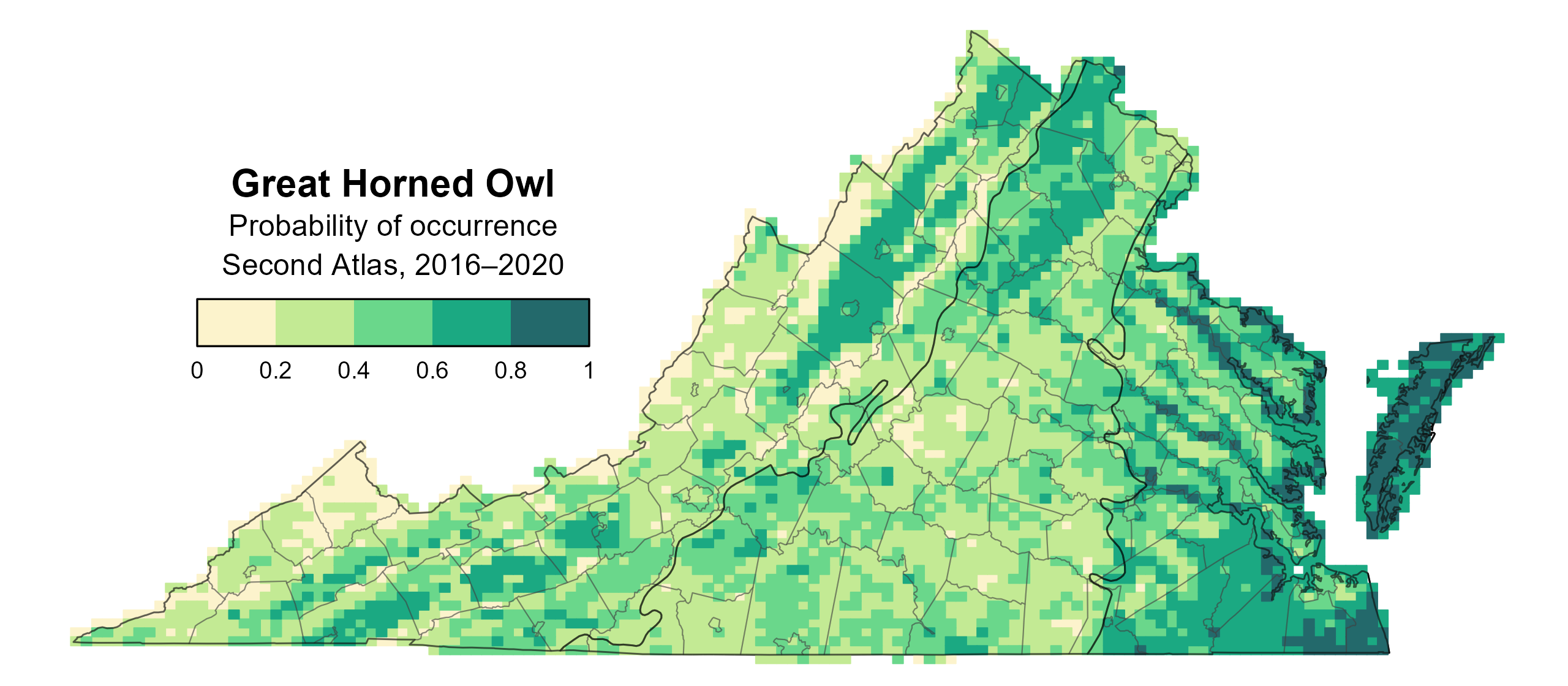

Great Horned Owls are found throughout the state but are most likely to occur in the Coastal Plain, especially in the southeastern corner, along major rivers, and on the Eastern Shore (Figure 1). They are also more likely to occur in rural valleys of the Mountains and Valleys region and the northern Piedmont (Figure 1). Great Horned Owl probability of occurrence is positively associated with the number of habitat types in a block, suggesting that it needs a mix of forest, forest edges, and open land for nesting and foraging.

Its distribution during the First Atlas and the change between Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Great Horned Owl breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

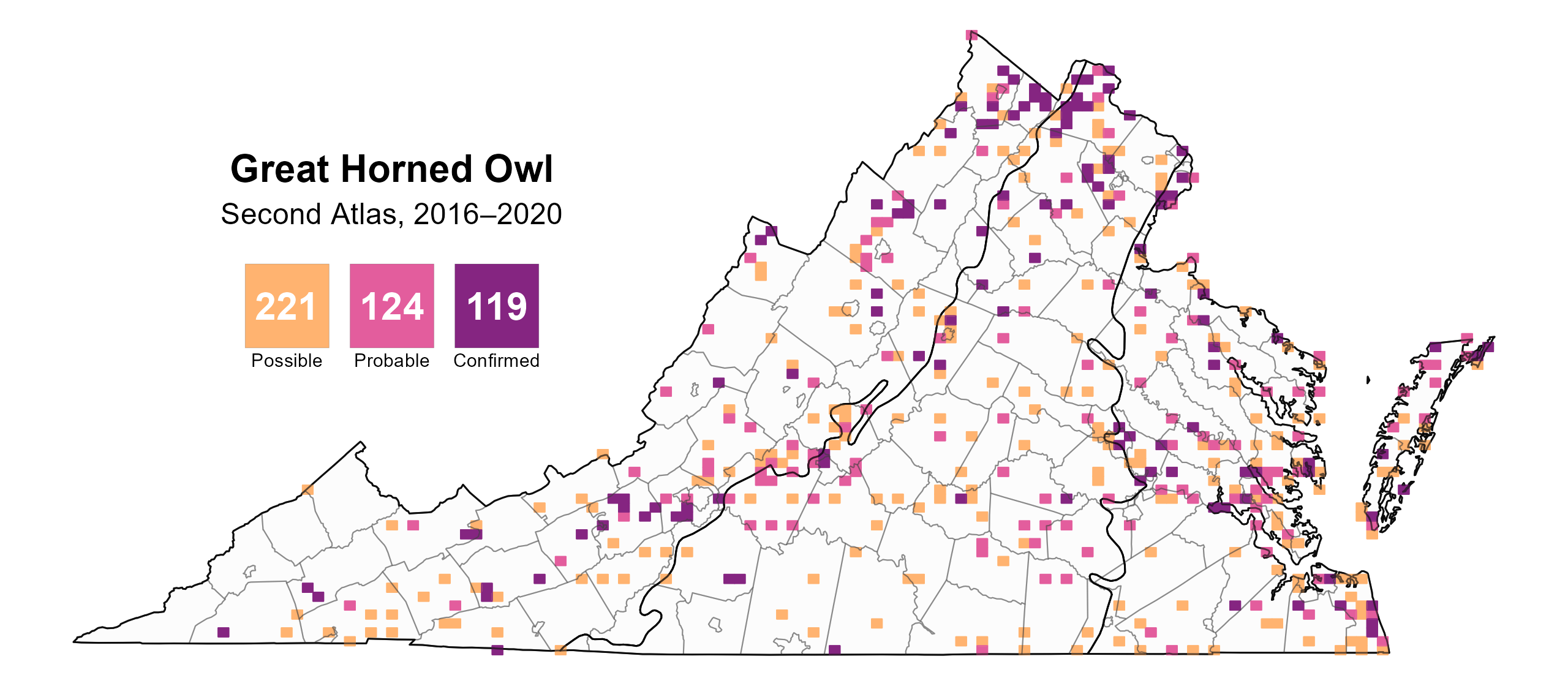

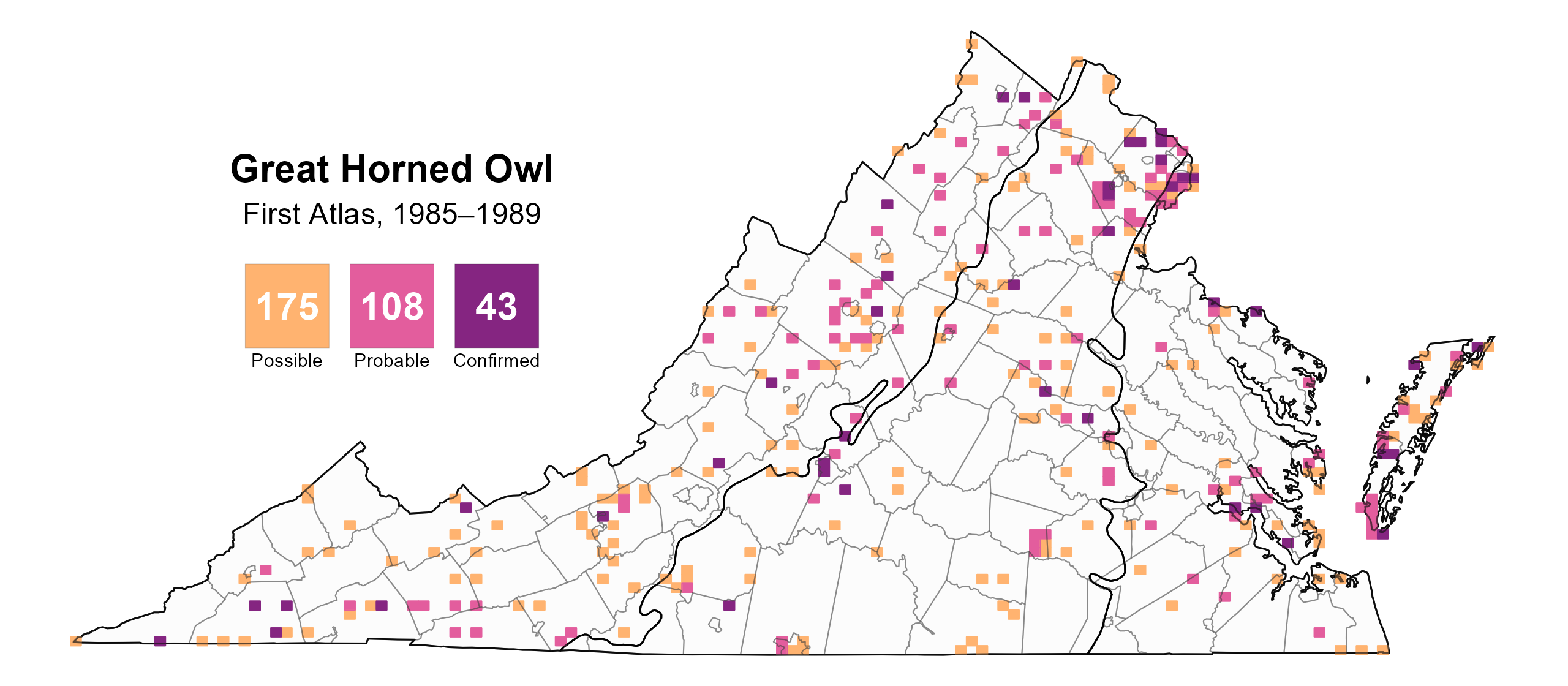

Throughout the state, Great Horned Owls were confirmed breeders in 119 blocks and 55 counties and found to be probable breeders in an additional 31 counties (Figure 2). Breeding observations were recorded in all three regions of the state during the First Atlas as well (Figure 3).

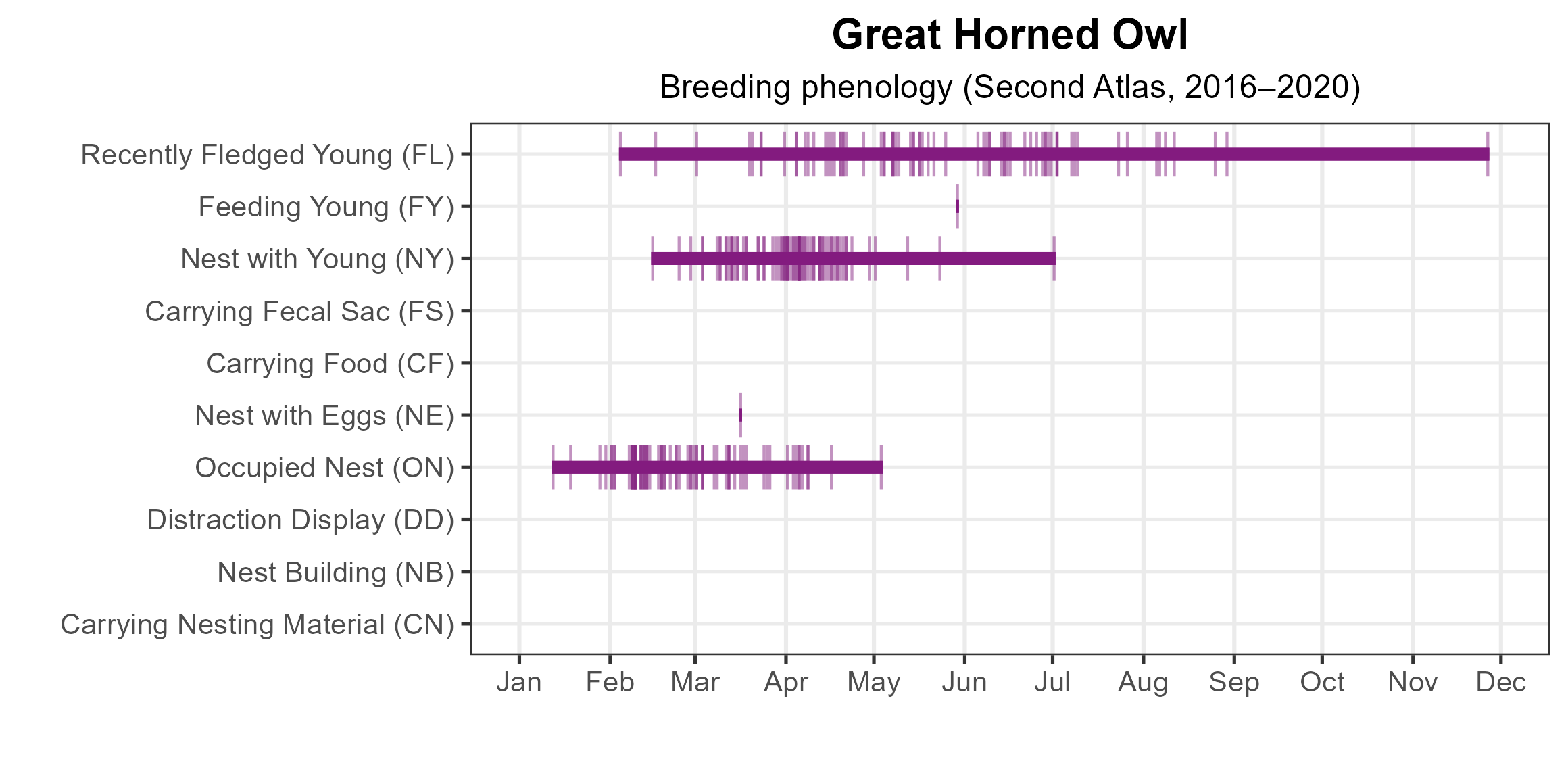

Breeding was confirmed as early as January 12 with the observation of occupied nests. Nests with young were observed between February 15 and July 1, and fledged young were documented between February 4 and November 26 (Figure 4).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Great Horned Owl breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Great Horned Owl breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Great Horned Owl phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Due to limited detections in the point count data, an abundance model for the Great Horned Owl was not produced. Additionally, the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not produce a credible population trend for the Great Horned Owl at any geographic scale. Although its numbers in the state have increased from the lows that resulted from DDT-induced population declines (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), it is unknown how the species has been faring in Virginia in recent decades.

Conservation

Given that there are no credible population trends for this species in Virginia or the region, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan classified the Great Horned Owl as an Assessment Priority Species (VDWR 2025). Population trend data are needed in order to evaluate whether the owl should be classified as a Virginia Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Generally, across their range, Great Horned Owl populations are considered robust and not in need of conservation attention (Artuso et al. 2022).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Artuso, C., C. S. Houston, D. G. Smith, and C. Rohner (2022). Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (N. D. Sly, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grhowl.01.1.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist, 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.