Introduction

The Great Egret shares a genus with the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias), with whom resemblance is obviously shared in structure if not coloration. In addition to its fine plumes, in breeding flush, the familiar yellow bill darkens, and the lores flush a vivid mint green. It inhabits a wide range of wetland habitats, distributed worldwide. In Virginia, it is a common summer resident and migrant, only locally common in winter, and an uncommon visitor elsewhere (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Alongside other egrets and herons, the Great Egret was hunted for its plumes in the millinery trade. By the early 1900s, Bailey (1913) reported that Virginia’s “white cranes” were few in number but still breeding in the Chickahominy region and along the James River. Its subsequent recovery, enabled by legal protections, is emblematic of successful bird conservation. Its generalist foraging and nesting habits have supported this recovery (McCrimmon et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

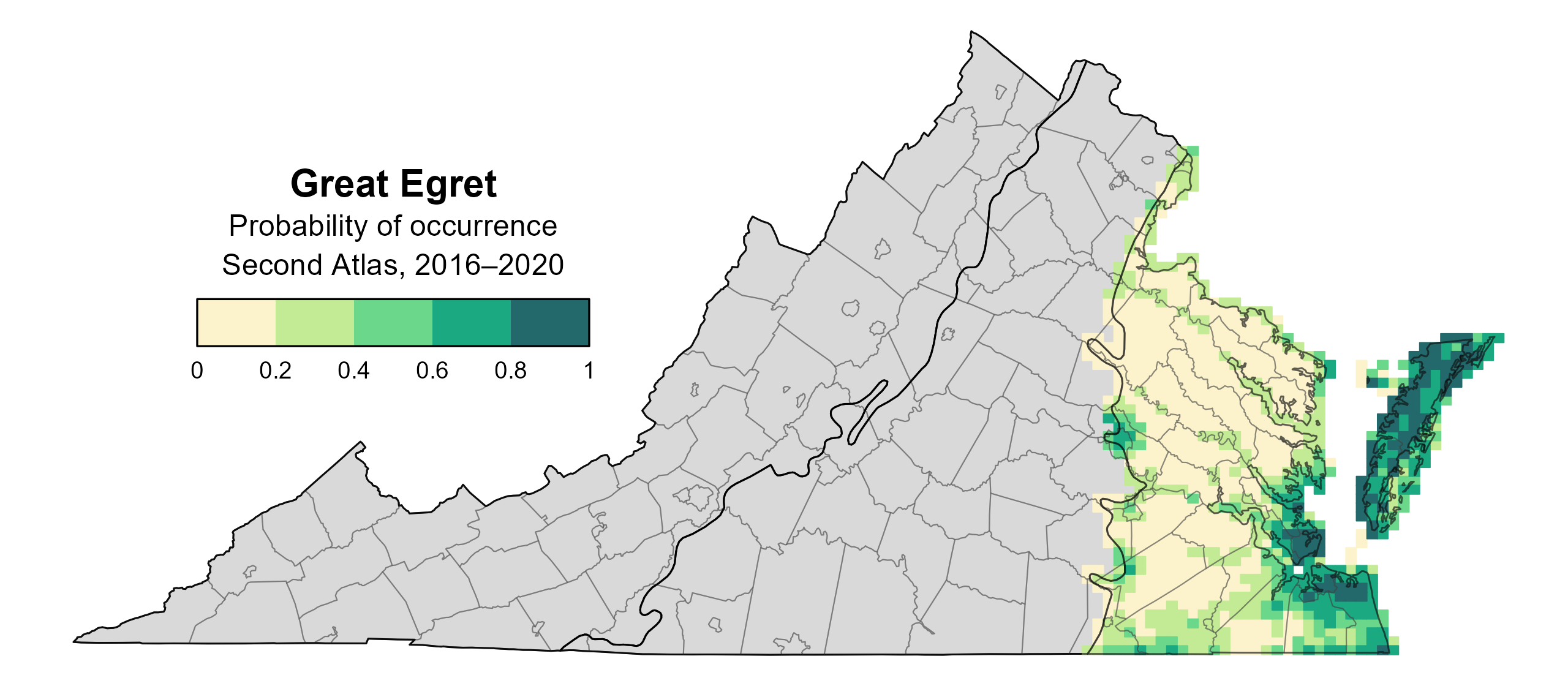

During the breeding season, Great Egrets are most likely to occur along major waterways in the outer Coastal Plain (Figure 1). Their occurrence is associated with areas that have low forest cover and a high diversity of habitat types, which likely reflects the increased likelihood of this species occurring in wetland/marsh habitats in blocks with more landcover types represented.

Occurrence in the First Atlas and change between Atlas periods could not be modeled (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its occurrence during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Figure 1: Great Egret breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

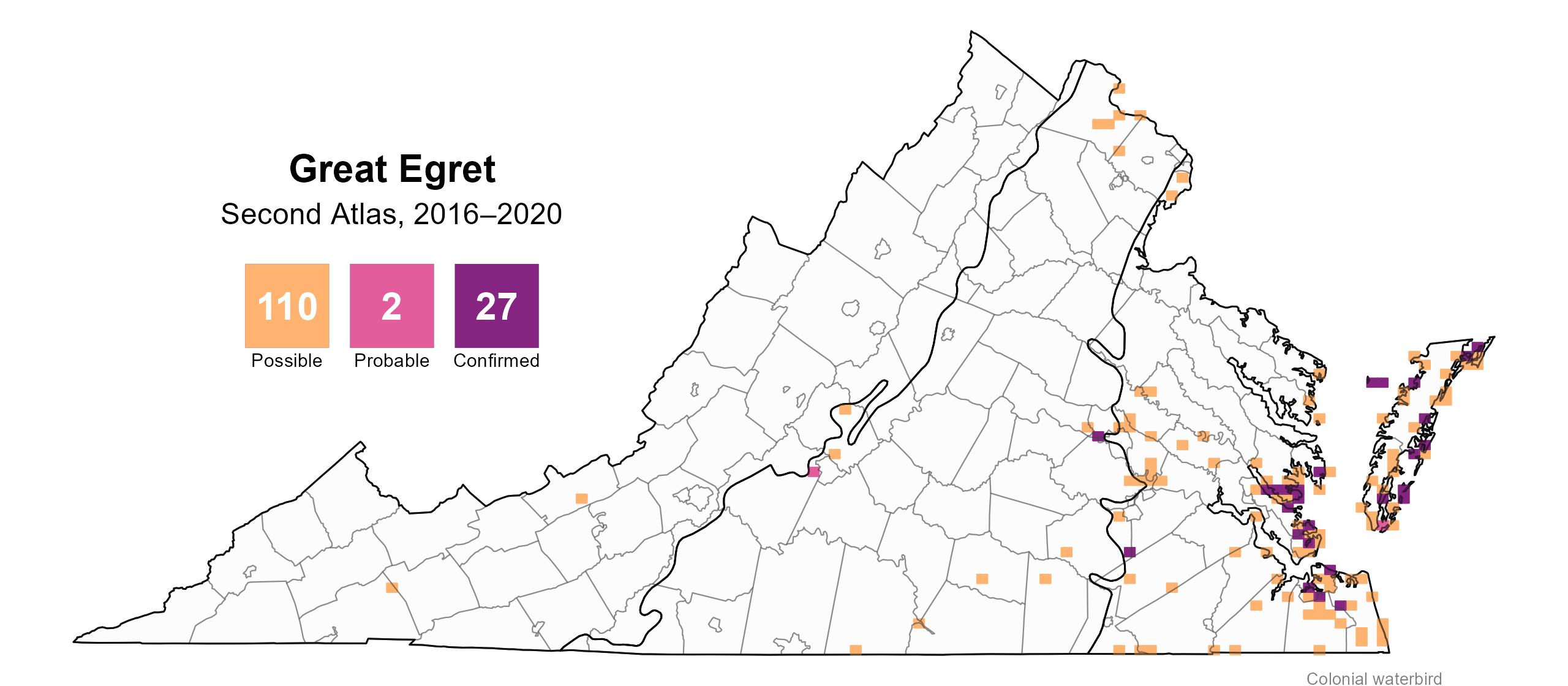

Great Egrets were confirmed breeders only in the Coastal Plain region, primarily near the mouths of waterways entering the Chesapeake Bay and on barrier islands (Figure 2). Though they were observed during the breeding season at sites in the Piedmont and Mountains and Valleys regions, no breeding colonies were confirmed outside the Coastal Plain.

They also bred at a limited number of inland sites. These included a mixed-species heronry along the James River in Henrico County, precisely on the fall line, and birds were observed carrying nesting material at Carson Wetland in Prince George County, where Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) and Great Blue Herons also nested.

In total, breeding was confirmed in 27 blocks across 13 counties. Notable sites in Accomack County included Tangier Island, Watts Island, Half Moon Island (bayside), and the Middle Mouth and Far Mouth heronries along the Chincoteague causeway. In Northampton County, colonies occurred in the back marshes of South Swash Bay, Chimney Pole Marsh, Cobb Island, and Wreck Island. Urban breeding was recorded in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Poquoson, with additional colonies along the York and James Rivers.

Heronries are conspicuous and, when accessible, breeding Great Egrets are readily confirmed due to their large size and visibility. However, colonies in more remote drainages are harder to detect, and aerial survey effort has been non-existent since 2013.

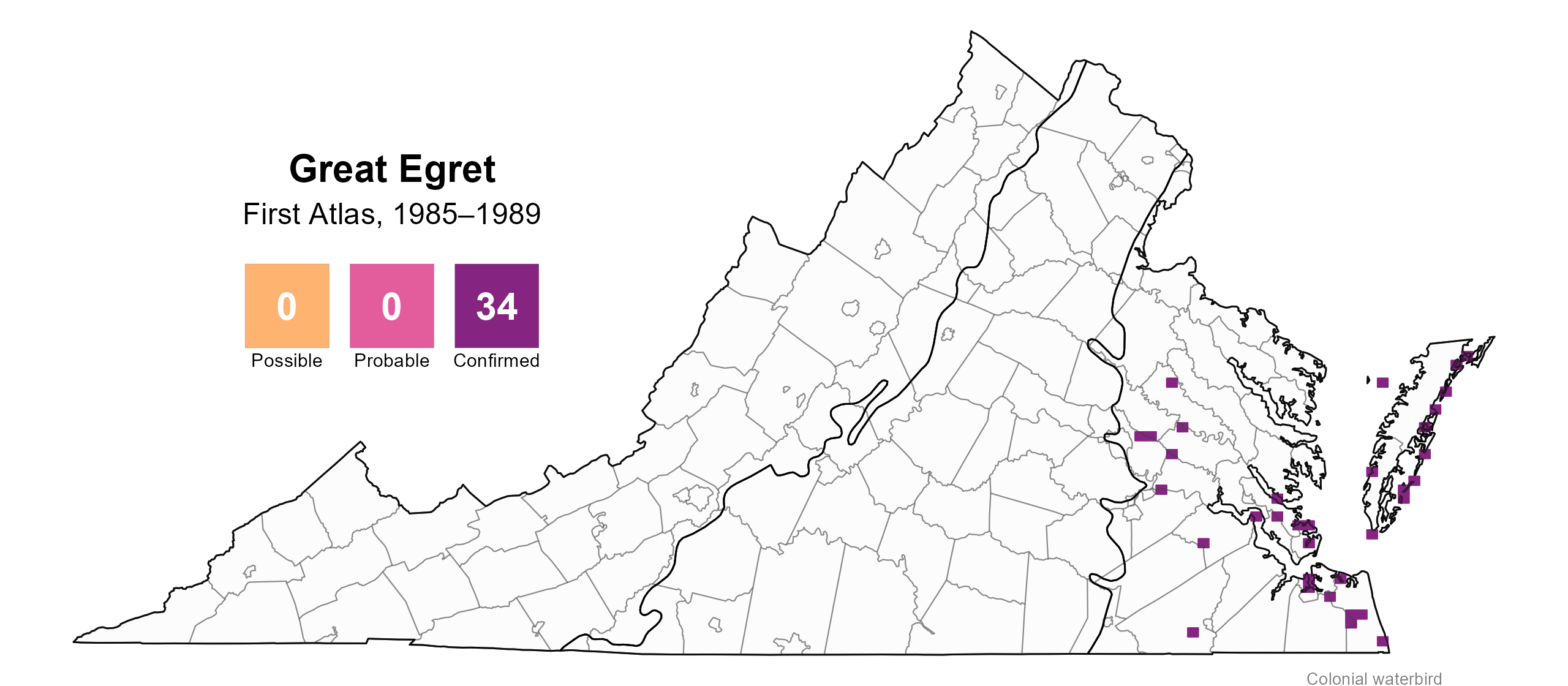

During the First Atlas, Great Egrets were also confirmed nesting with Great Blue Herons along major rivers, including at some inland sites where they were not confirmed during the Second Atlas (Figure 3). Colony sites of wading birds tend to move over time. Several Atlantic colonies with Great Egrets during the First Atlas were not present during the Second Atlas, for example. Despite local site turnover, the species’ distribution has expanded over the past 30 years and now extends into the Piedmont (Watts et al. 2024).

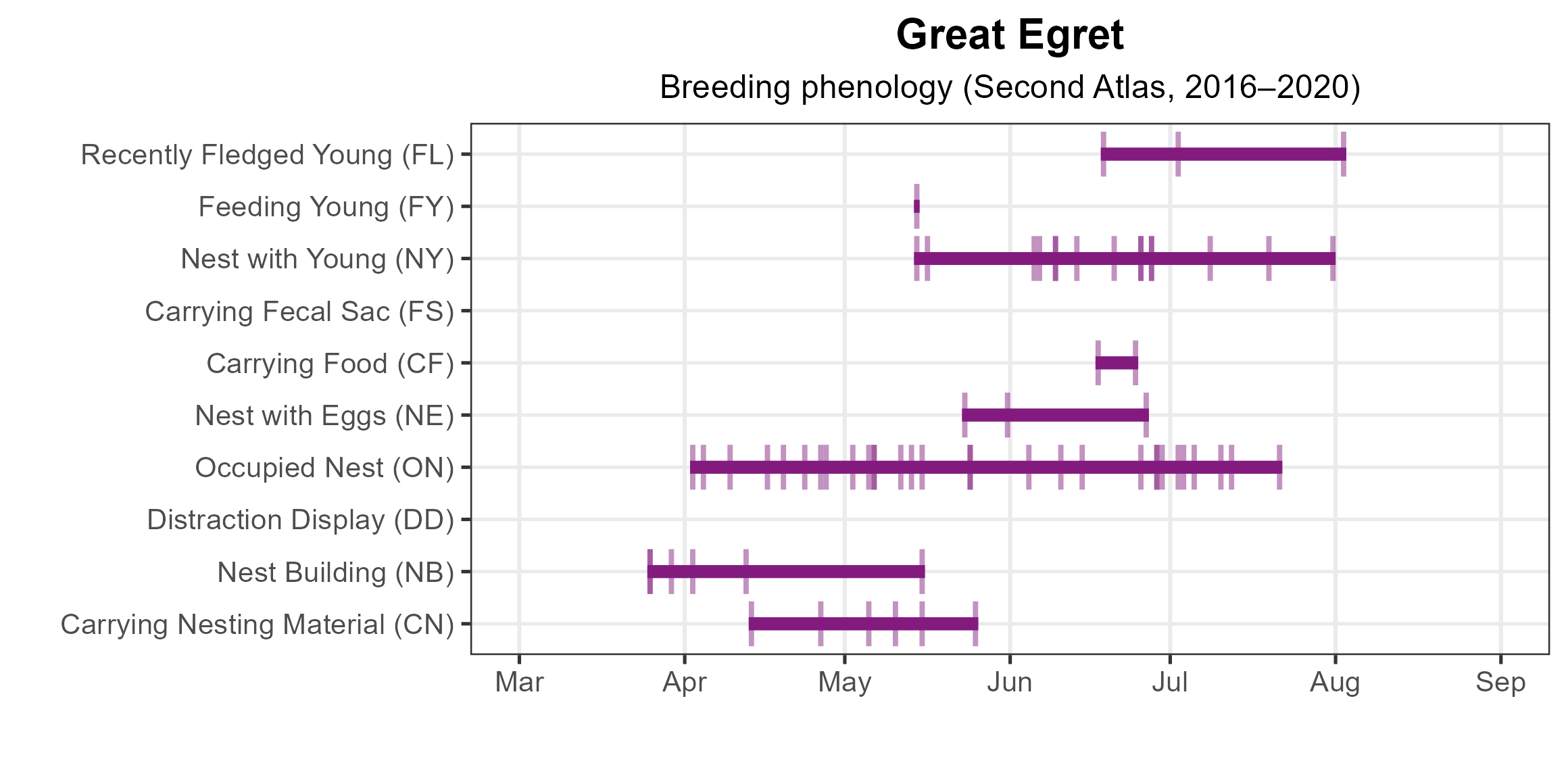

Observations of nest building were recorded from March 25 through May 15. Eggs were rarely visible, but nestlings were recorded between May 14 and July 31 (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Great Egret breeding observations from the (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Great Egret breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Great Egret phenology: confirmed breeding codes (Second Atlas). This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Great Egret had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Great Egret colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy, are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

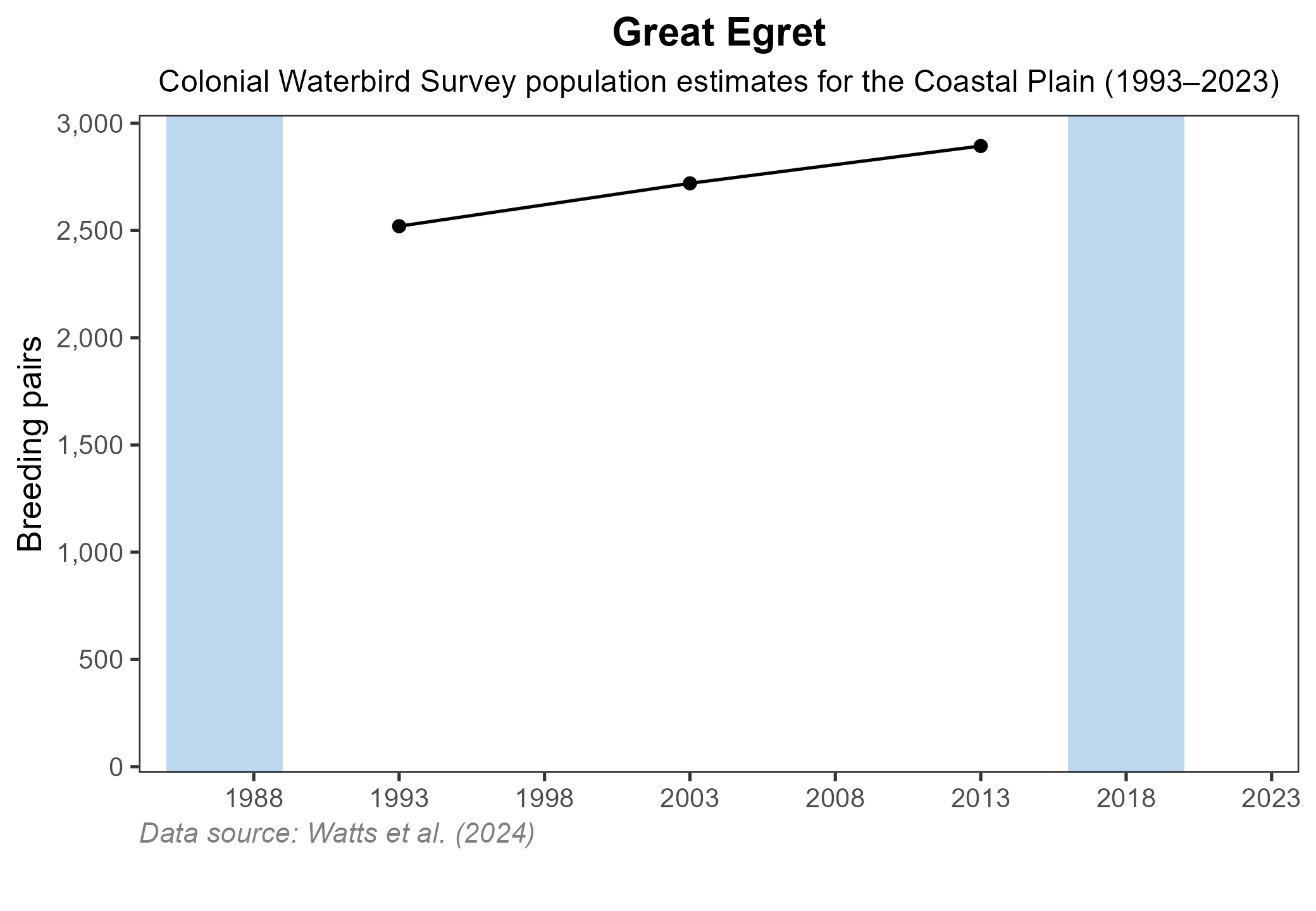

The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys show that by 1993, numbers had tripled since the early 1970s (Williams et al. 1998). From 1993 to 2013, the population rose modestly from 2,520 to 2,894 breeding pairs (Watts et al. 2019; Watts et al. 2024).

However, Great Egrets are no longer surveyed completely because the extent of their inland colonies, which they typically co-occupy alongside Great Blue Herons, are so extensive that it has become both logistically and financially infeasible. The statewide population is likely around 3,000 pairs as of 2024, with an increasing population in the Chowan drainage south of the James River, an area that is not surveyed (Bryan Watts, personal communication).

Figure 4: Great Egret population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Great Egret is not currently a conservation concern in Virginia, with expanding populations and continued range growth.

However, like all colonial waterbirds, they remain vulnerable to disturbance. While intentional disturbance is now rare, inadvertent disturbance from human activity can still pose a threat. The species appears to tolerate some level of human disturbance (McCrimmon et al. 2020) as evidenced by their presence of breeding colonies in urban residential areas. Protection of both breeding colonies and foraging sites is necessary.

Coastal populations face rising sea levels and marsh subsidence that threaten colonies. Nonetheless, current trends suggest the species is stable or increasing and likely to continue expanding its range in Virginia.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated, Lynchburg, VA, USA.

McCrimmon, D. A., Jr., J. C. Ogden, G. T. Bancroft, A. Martínez-Vilalta, A. Motis, G. M. Kirwan, and P. F. D. Boesman (2020). Great Egeret (Ardea alba), version 1.0. In Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.greegr.01

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. College of William & Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-19-06. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. Boettcher, and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. College of William & Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University CCBTR-24-12. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Williams, B., B. Akers, M. Beck, R. Beck, and J. Via (1998). The 1997 colonial and beach-nesting waterbirds survey of the Virginia barrier islands. The Raven 69:15–31.