Introduction

Weighing in at over four pounds, the Great Black-backed Gull is the largest gull in the world and carries itself accordingly. It possesses a striking black back contrasting with its snow-white head and bubblegum pink legs. This seafaring bird has earned a fearsome reputation as both scavenger and predator, yet beneath its imposing exterior, it is also a devoted parent. Additionally, individuals can live over 19 years in the wild.

In Virginia, Great Black-backed Gulls nest on barrier islands, often alongside Herring Gulls (Larus smithsonianus), and similar to Herring Gulls, breeding Great Black-backed Gulls in Virginia are a recent phenomenon. Birds of Virginia (Bailey 1913) makes no mention of the species at all, and the first documented breeding record did not occur until 1970 at Fisherman Island (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Today, it is a common to abundant permanent resident along the coast and is a locally uncommon migrant and winter visitor up tidal rivers and at landfills in the Piedmont (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Breeding Distribution

The Great Black-backed Gull was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Great Black-backed Gull only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Given the breeding biology of the species, the Great Black-backed Gull is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Confirmation of breeding was based on records generated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

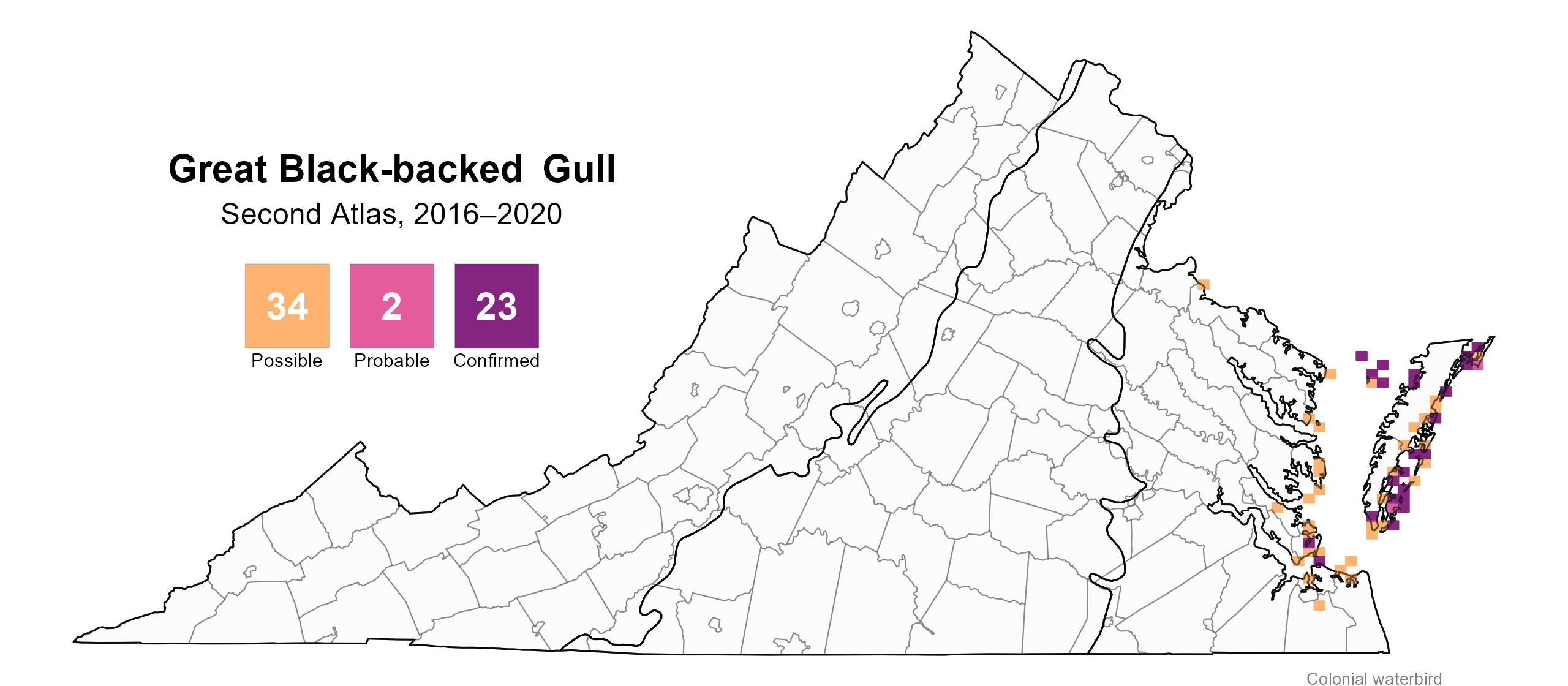

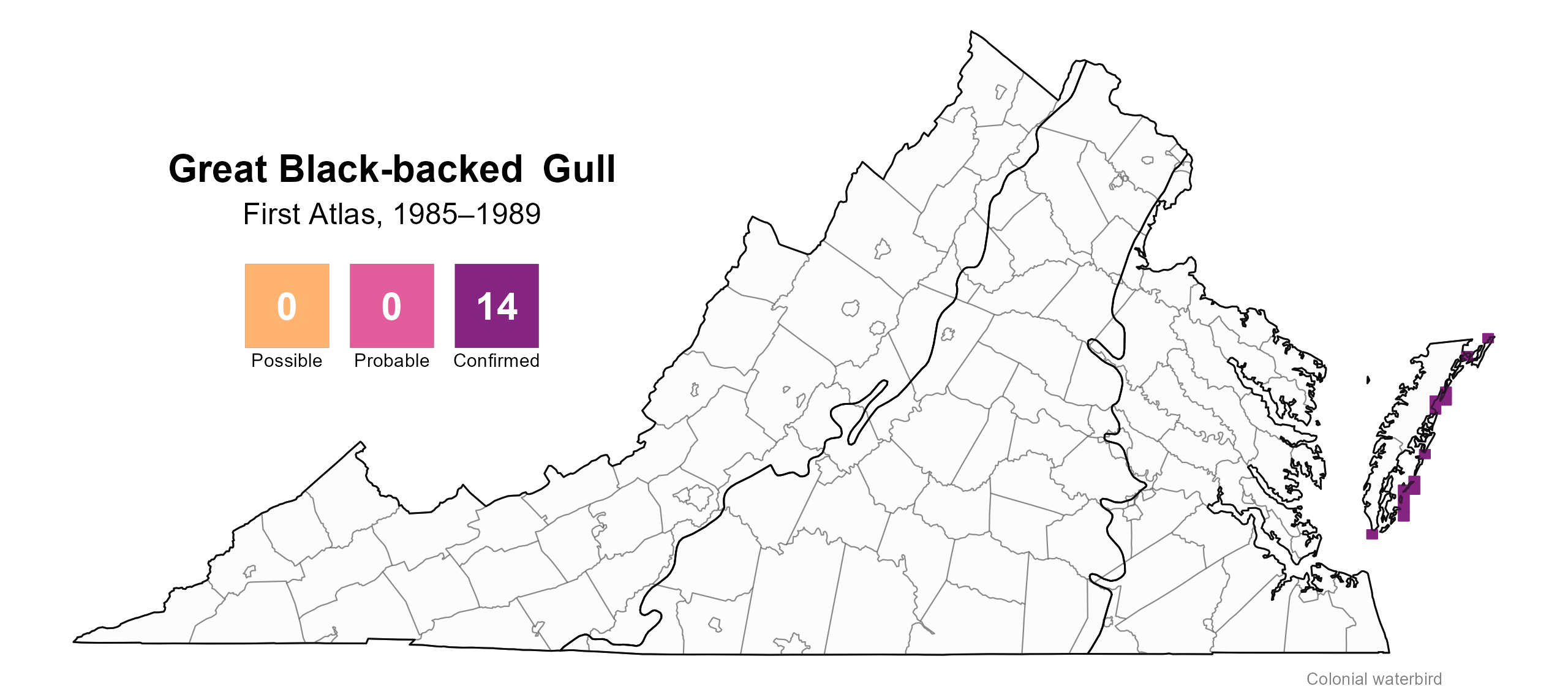

Great Black-backed Gulls were confirmed breeders in Atlantic and Chesapeake Bay marshes, as well as manmade sites at the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT) and the concrete ships off Kiptopeke State Park (Figure 1). Breeding was confirmed in 23 blocks in two counties and two cities (Accomack and Northampton and Hampton and Norfolk, respectively). The distribution of breeding sites was largely similar to that during the First Atlas (Figure 2). As the population expanded, they colonized new breeding sites in the Hampton Roads region and Chesapeake Bay islands and marshes in Tangier Sound.

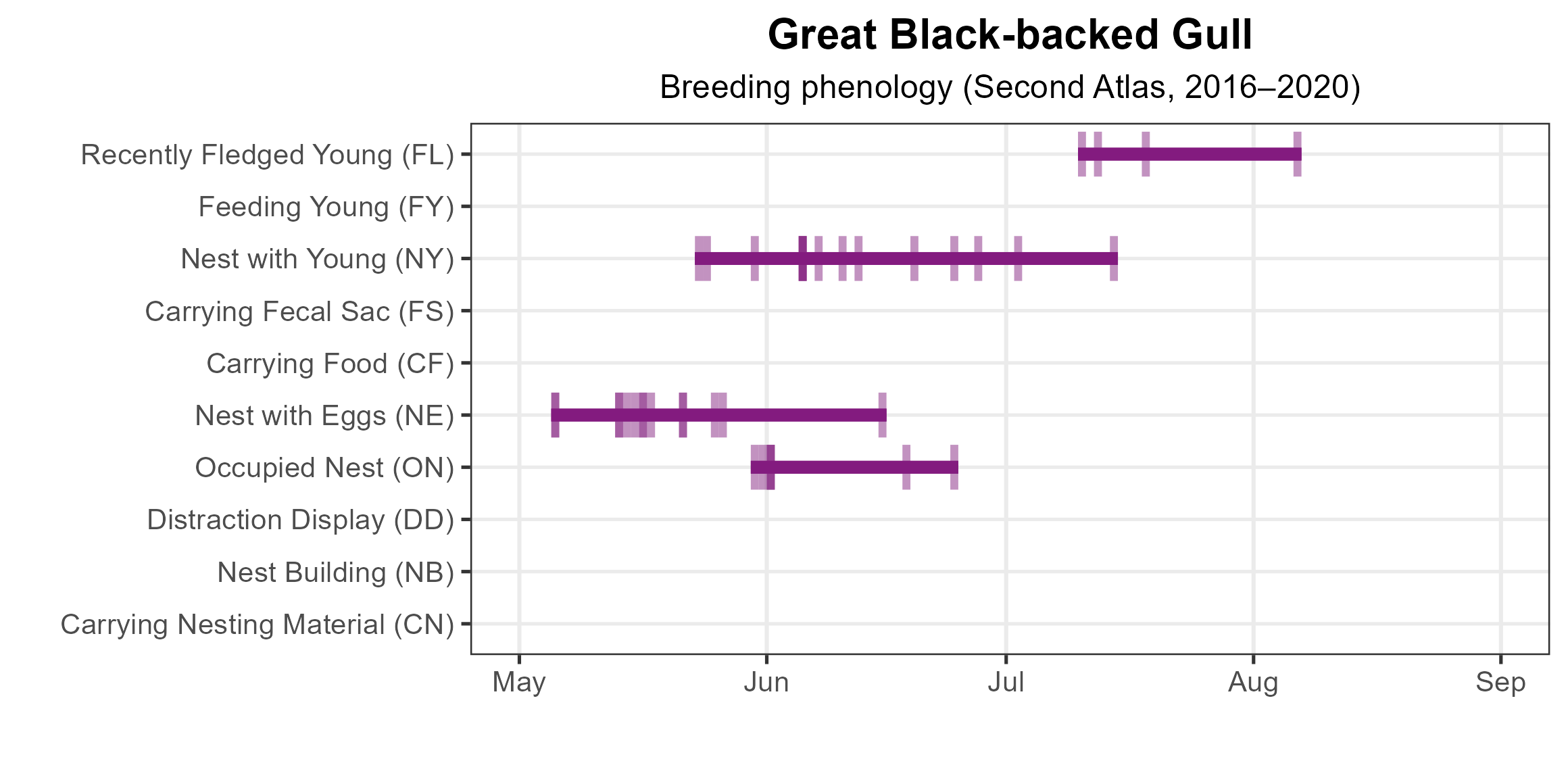

Great Black-backed Gulls were observed with eggs from May 5 to June 15 and with young in the nest until July 14 (Figure 3). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Great Black-backed Gull, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Great Black-backed Gull breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Great Black-backed Gull breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Great Black-backed Gull phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Great Black-backed Gulls had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Great Black-backed Gull colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey is displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

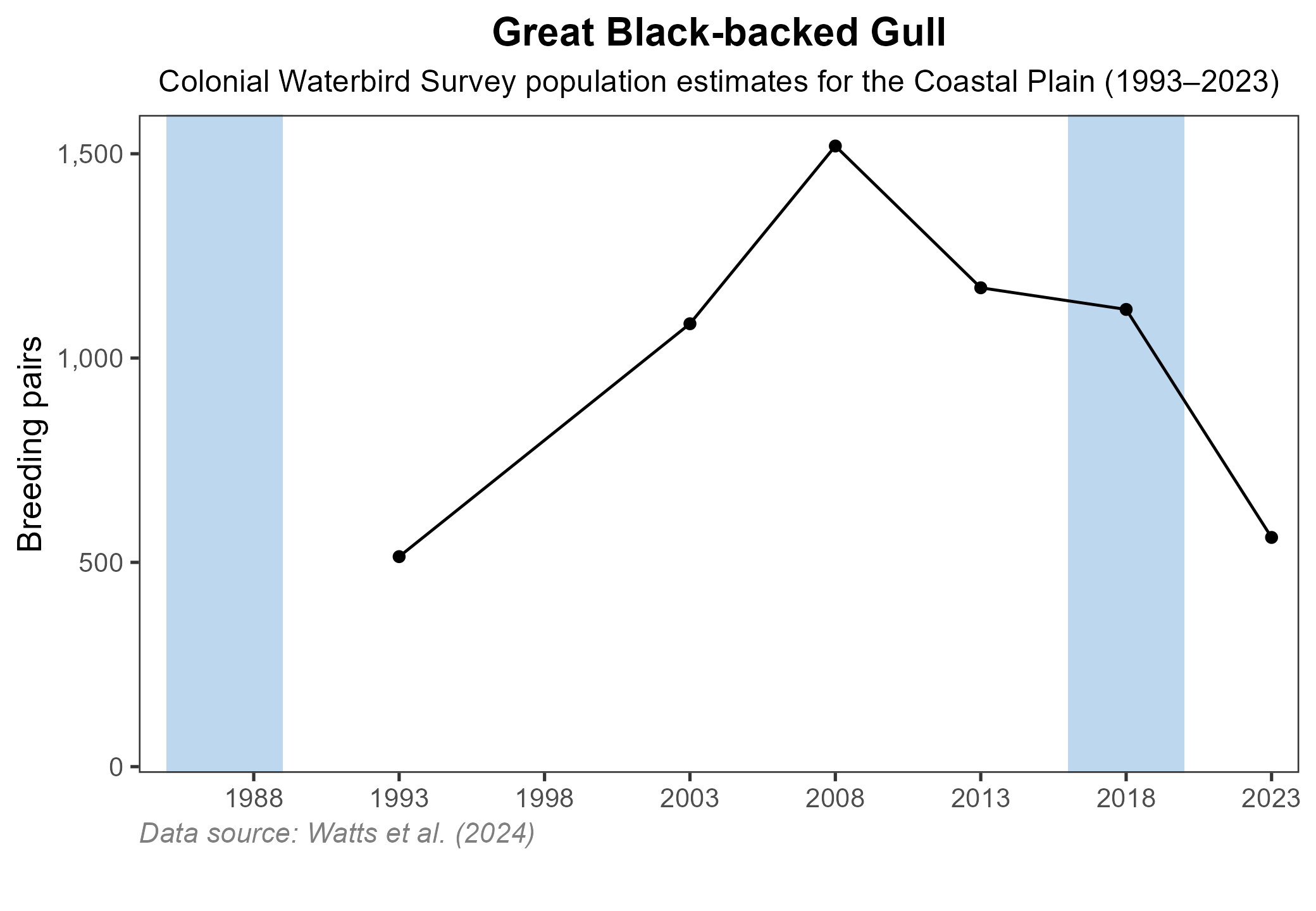

At the time of the First Atlas, annual counts of breeding Great Black-backed Gulls were increasing, riding the tide of their range expansion into Virginia (Williams et al. 1993). Based on the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, the species increased from 514 breeding pairs in 1993 to a high of 1,519 in 2008 (Watts et al. 2019, 2024). During the Second Atlas, populations had begun to slump, and by 2023, the Great Black-backed Gull breeding population sat nearly where it was in 1993, at 561 pairs (Watts et al. 2024; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Great Black-backed Gull population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Great Black-backed Gull is not currently considered a species of concern in Virginia. Overall, the species is undergoing a range expansion and should be expected to remain a common sight on Virginia’s shores, despite fluctuations in populations. However, like other marsh-nesting species, it is vulnerable to the loss of breeding sites to sea-level rise and marsh subsidence. Great Black-backed Gulls have sometimes been implicated in the decline in other barrier island nesting species in Virginia, particularly terns and skimmers, because Black-backs are nest predators and nest site competitors (O’Connell and Beck 2003). A relatively small number of Great Black-backed Gulls nested on the HRBT and were displaced in 2020 when the South Island HRBT expansion project paved over the former nesting site, and based on surveys of the area, they have successfully been drawn to Fort Wool (Rip-Rap Island) (Sweeney et al. 2024).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated, Lynchburg, VA, USA.

O’Connell, T. J., and R. A. Beck (2003). Gull predation limits nesting success of terns and skimmers on the Virginia barrier islands. Journal of Field Ornithology 74:66–73.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Sweeney, C., K. Hunt, J. Fraser, and S. Karpanty (2024). Assessing avian response to the relocation of Virginia’s largest seabird colony, 2024 annual report. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Williams, B., B. Akers, R. A. Beck, and J. Via (1993). The 1992 colonial and beach-nesting waterbird survey of the Virginia barrier islands. The Raven 64:24–29.