Introduction

The Golden-crowned Kinglet in Virginia is restricted as a breeder to high-elevation spruce-fir forests (Wilson and Watts 2012). However, they are common winter residents throughout the state and regularly join mixed-species flocks led by the species Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) and Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis).

These boldly marked little birds with a crest the color of butter nest high along the trunks of conifer trees, such as red spruce (Picea rubens). Given their small size (only slightly larger than a hummingbird) and tendency to remain high in the forest canopy, one of the best ways to find Golden-crowned Kinglets is to listen for their ascending and accelerating series of high-pitched tsee notes (Swanson et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

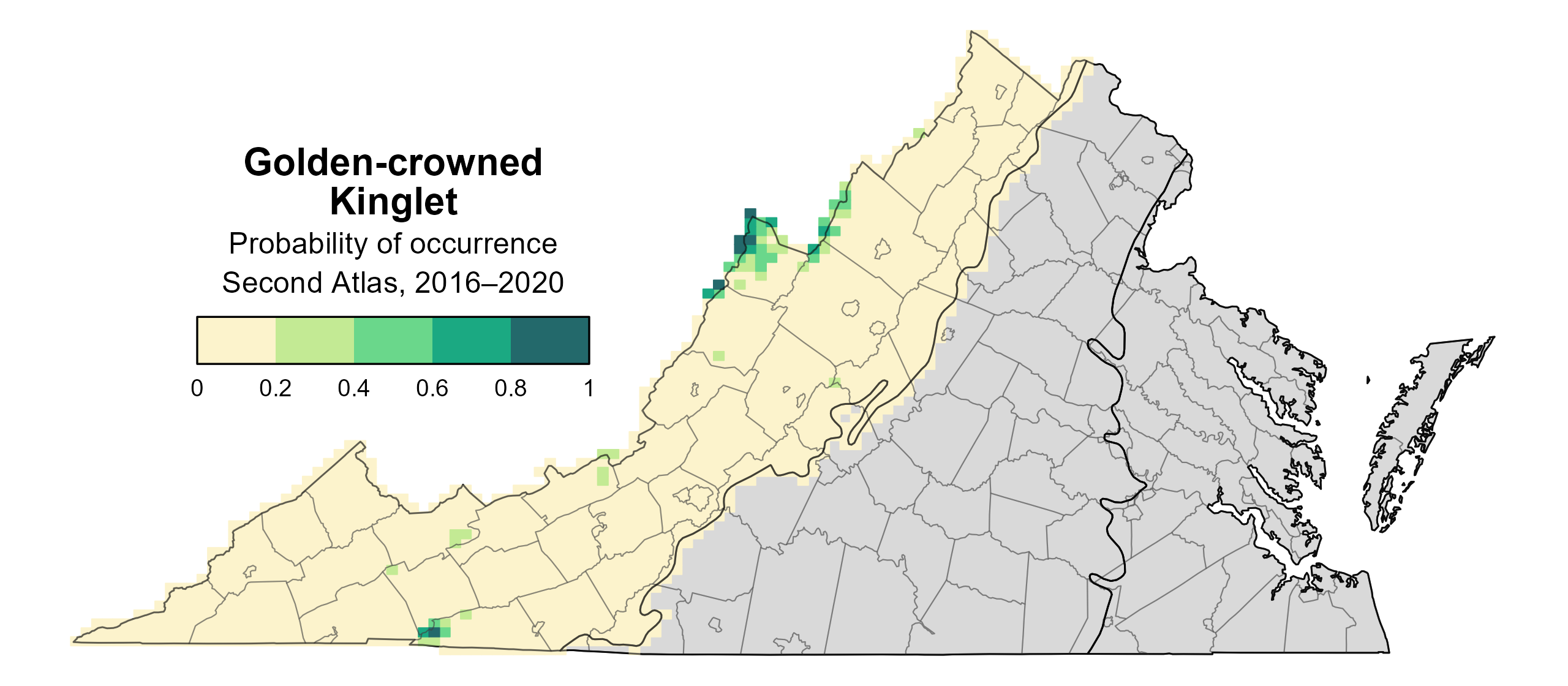

Virginia is near the southern end of the Golden-crowned Kinglet’s eastern breeding range, which extends southward into western North Carolina along the Appalachian Mountains (Swanson et al. 2020), and the species is confined to the Mountains and Valleys region within the Commonwealth. In this region, they are most likely to occur in a limited area consisting of isolated high-elevation forests in Augusta, Bath, Grayson, Highland, and Rockingham (Figure 1). Though typically associated with spruce forests, the species is also found in mixed areas of spruce and northern hardwood forests in Virginia based on data from the Second Atlas.

Due to data limitations, Golden-crowned Kinglet’s distribution during the First Atlas and its change between Atlas periods could not be modeled (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on where this species occurred during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Golden-crowned Kinglet breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

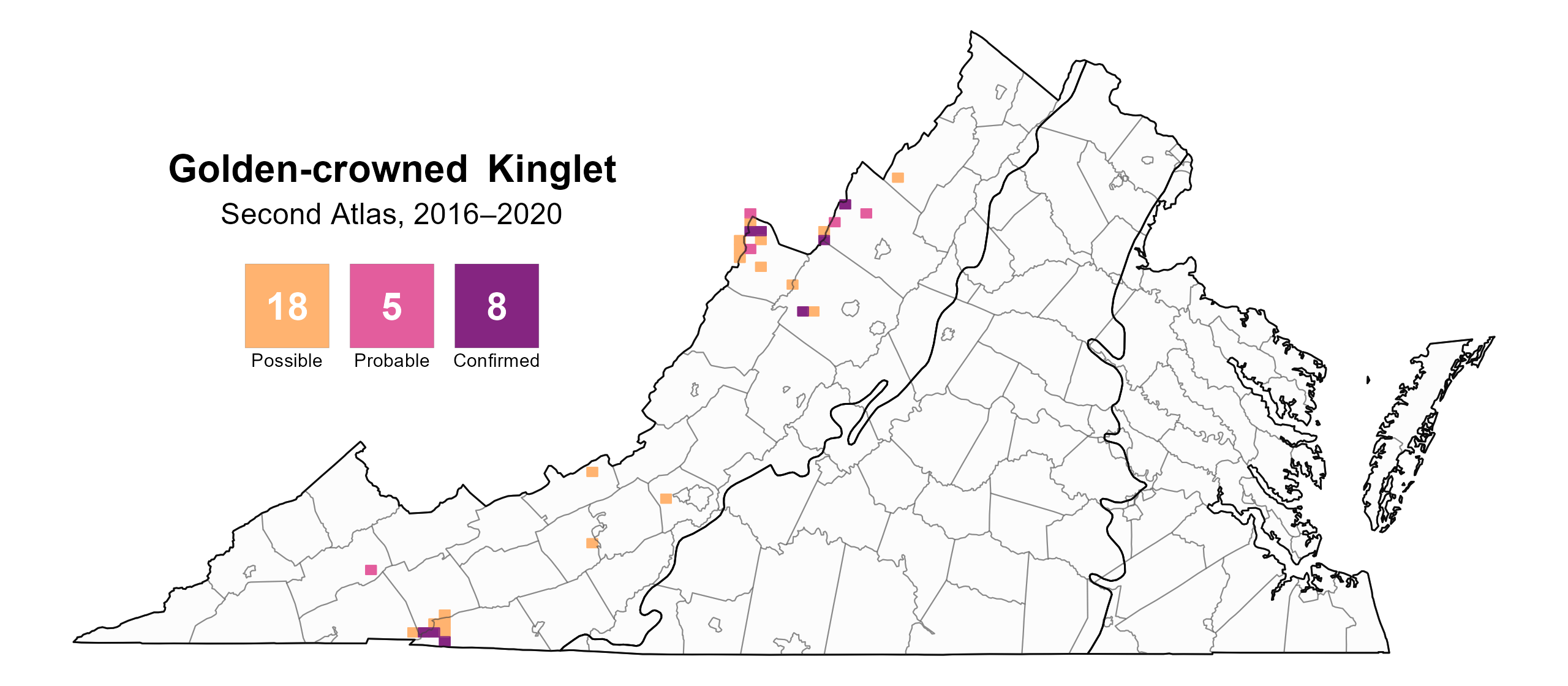

Golden-crowned Kinglets were confirmed breeders in eight blocks and four counties, including the Hall Spring area of Shenandoah Mountain in Rockingham County, Elliot Knob in Augusta County, Laurel Fork in Highland County, and Grayson Highlands State Park, Whitetop Mountain, and Mount Rogers in Grayson County. They were also documented as probable breeders on Beartown Mountain within the Clinch Wildlife Management Area in Russell County and on Whitetop Mountain and Mount Rogers in Smyth County (Figure 2). The number of blocks with breeding observations doubled during the Second Atlas relative to the First Atlas (Figures 2 and 3). This difference mirrors the positive population trend for the species in the Atlantic Flyway region during this period (see Population Status); however, it is also important to note that survey effort was considerably greater during the Second Atlas.

Although breeding was confirmed primarily through observations of recently fledged young (June 15 – August 10), there were two observations of adults feeding young and one each of adults carrying food and nesting material (Figure 4).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Golden-crowned Kinglet breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Golden-crowned Kinglet breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Golden-crowned Kinglet phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Abundance could not be modeled for Golden-crowned Kinglet due to the low number of detections of the species during Atlas point count surveys. Similarly, the species is not documented in Virginia through the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS); thus, a population trend could not be estimated for the state. However, at the Atlantic Flyway level, BBS data show that the Golden-crowned Kinglet experienced a significant 2.62% annual increase from 1966–2022, and between Atlases, its population increased by a significant 2.1% per year from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). This trend is consistent with a numerical increase in the number of breeding season records noted in Highland County between 1985 and 2003 and in the number of western counties where such records have been documented over time (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Figure 5: Golden-crowned Kinglet population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

In a study of breeding bird communities associated with high-elevation forests in Virginia, Lessig (2008) found the distribution of Golden-crowned Kinglets to range between 3,400 ft (1036 m) and 5,450 ft (1661 m). The species is but one of a suite of birds that is dependent on such forests for breeding in the Commonwealth (Wilson and Watts 2012). Given the narrow elevational ranges at which these “high-island” forests occur, they are found in relative isolation from one another across the landscape. As such, these forests are susceptible to the effects of climate change, which could lead to their replacement by plant communities typically found at lower elevations (Wilson and Watts 2012). Despite the vulnerability of the habitat on which they depend, Golden-crowned Kinglets currently appear to be faring well in Virginia and beyond, and they are likely benefitting from habitat conservation efforts by partnerships such as the Southern Appalachian Spruce Restoration Initiative.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Lessig, H. (2008). Species distribution and richness patterns of bird communities in the high elevation forests of Virginia. Master’s Thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s Birdlife: An Annotated Checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Swanson, D. L., J. L. Ingold, and R. Galati (2020). Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.gockin.01.

Wilson, M. and B. Watts (2012). The Virginia avian heritage project: a report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.