Introduction

The Common Raven is renowned worldwide for its intelligence and close association with humans. With such intelligence also comes a capacity for play, exemplified by its ability to manipulate objects and perform aerial acrobatics. With its broad wedge-shaped tail and shaggy black beard, the raven stands head and shoulders above its corvid cousins. At more than four times the weight of the American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), it is among the heaviest of all songbirds (Boarman and Heinrich 2020).

Although widespread across the western and northern parts of North America, Common Ravens in the eastern U.S. were historically restricted to the Appalachian Mountains. However, after widespread persecution and decline during European colonization, the species has recently expanded from its refuge in the Appalachian Mountains into lower elevations (Hackworth et al. 2019). In fact, in the mountains of Virginia and West Virginia, researchers found that Common Ravens were most likely to breed on large, exposed cliff faces and that nests at elevations below 1,900 ft (580 m) fledged more young than nests at higher elevations (Hooper et al. 1975; Hooper 1977; Hackworth et al. 2022), suggesting expansion to lower elevations could continue.

Breeding Distribution

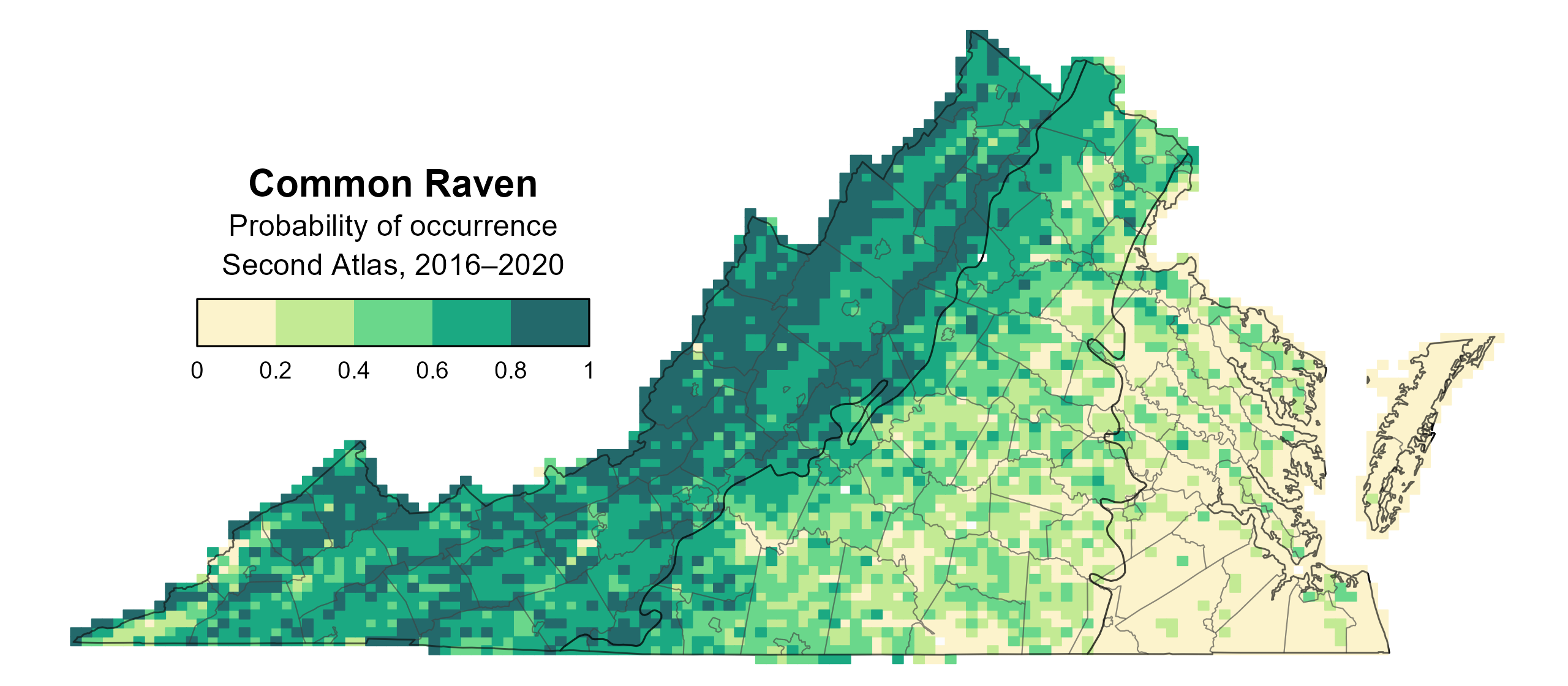

The Common Raven is primarily found in the Mountains and Valleys region, while it is moderately likely to occur in the Piedmont region and less likely to occur in the Coastal Plain region (Figure 1). The likelihood a Common Raven occurs in a block increases as the proportion of grassland/shrubland habitat, forests, agricultural lands, and developed land cover increases. Its occurrence is also positively associated with forest patch size.

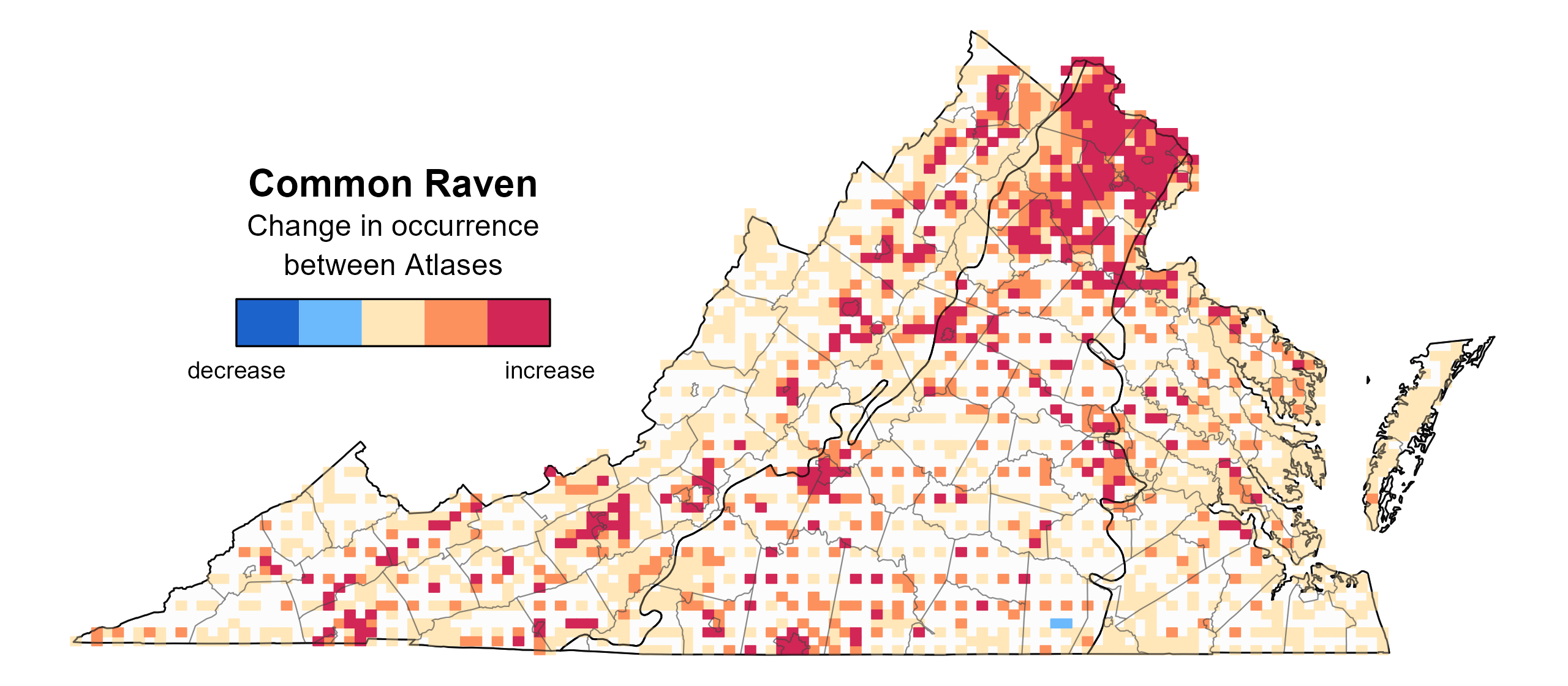

Between Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the Common Raven’s likelihood of occurrence increased substantially in urban areas across much of the Mountains and Valleys and Piedmont regions, especially in the Northern Virginia area (Figure 3). This increase is in line with its population increase in the state during this period (see Population Status).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Common Raven breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

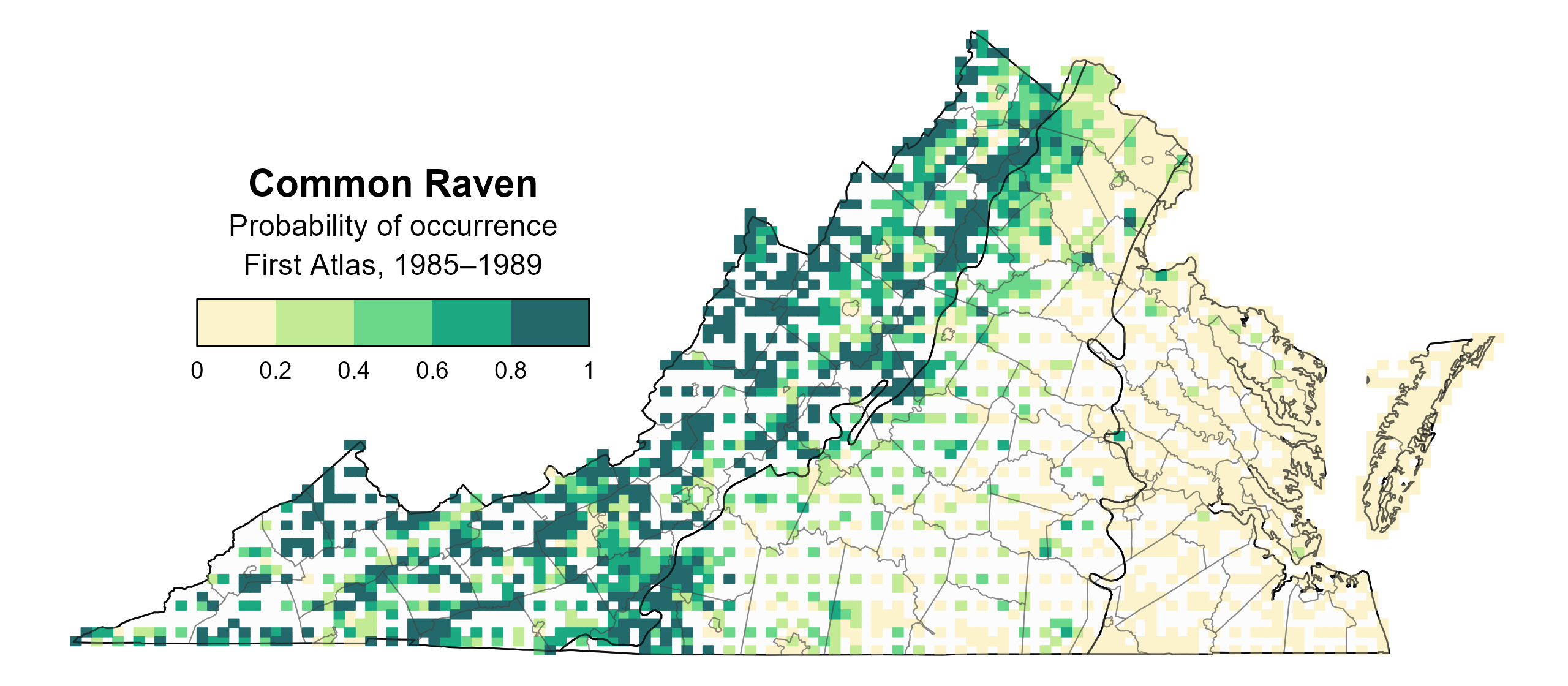

Figure 2: Common Raven breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Common Raven change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

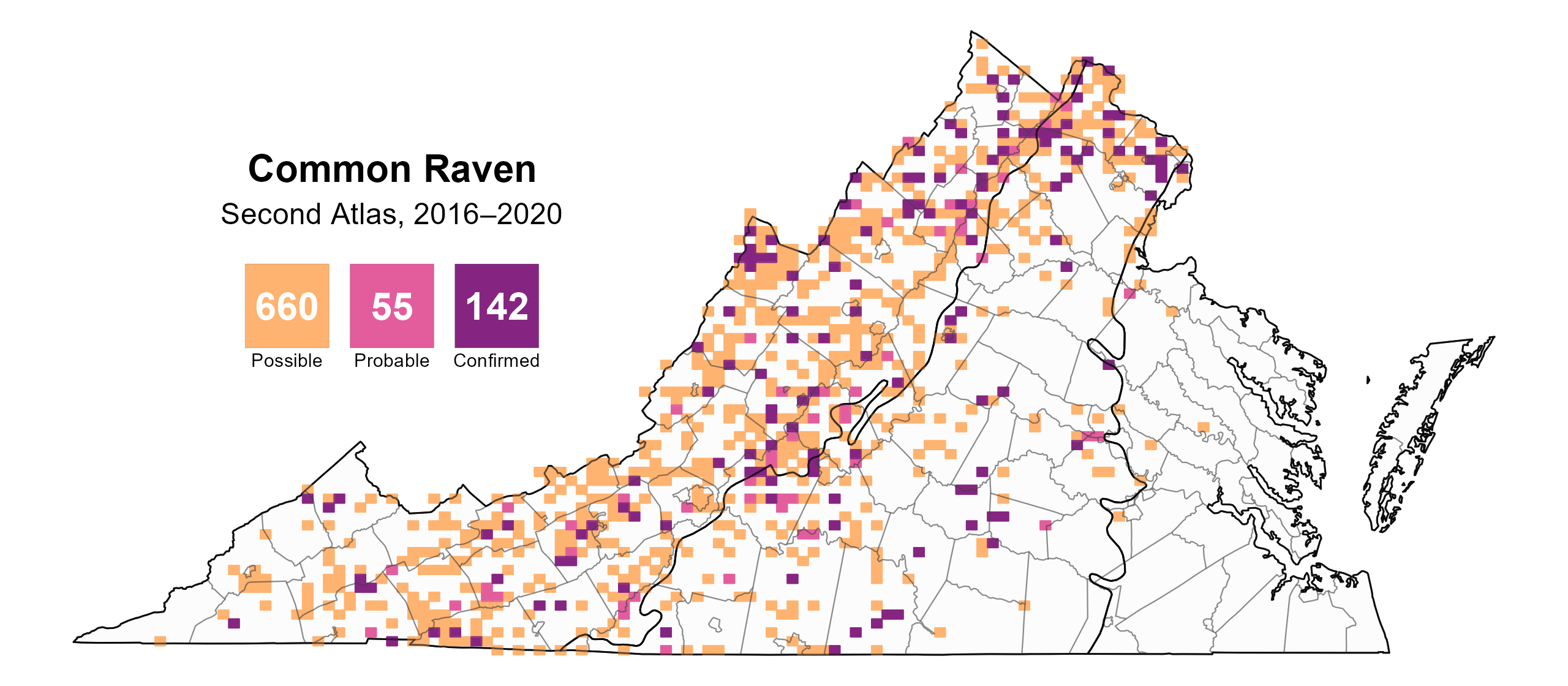

The Common Raven was a confirmed breeder in 142 blocks and 50 counties and a probable breeder in an additional seven counties (Figure 4). The Common Raven was formerly considered uncommon and local away from the Blue Ridge Mountains (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). During the First Atlas, it was only known to breed at a few sites in the Piedmont, the furthest east of which was in Henrico County (Figure 5).

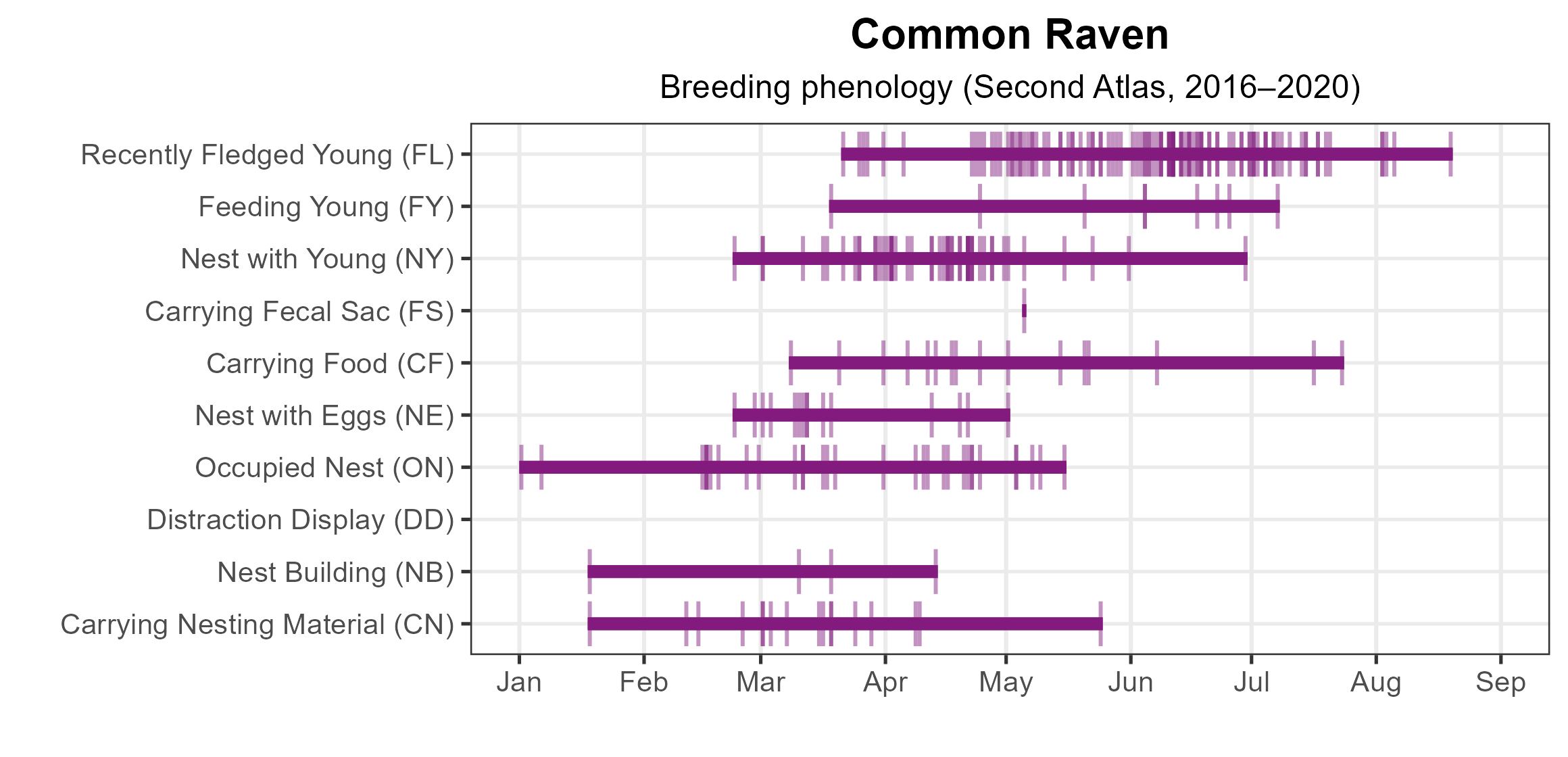

Ravens are early nesters; they were documented building or renovating nests throughout much of the year (Figure 6). Nest building began in earnest in January, with eggs documented starting February 23. Breeding continued to be recorded through late summer, with recently fledged young seen as late as August 19.

For more general information on the breeding habits of the Common Raven, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Common Raven breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Common Raven breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Common Raven phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

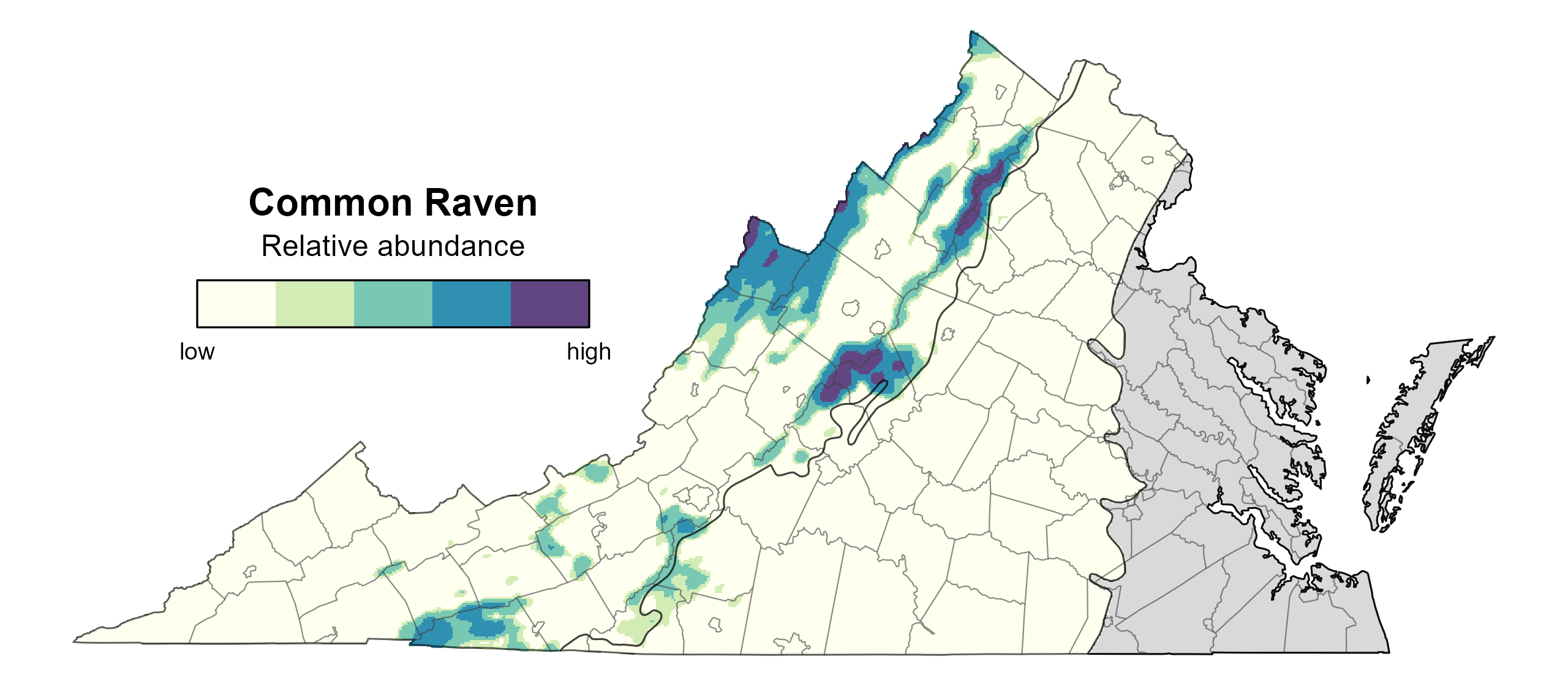

Common Raven relative abundance was estimated to be highest along the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains (Figure 7). Abundance was also predicted to be relatively high in the vicinities of Mount Rogers and Whitetop Mountain (Grayson and Smyth Counties).

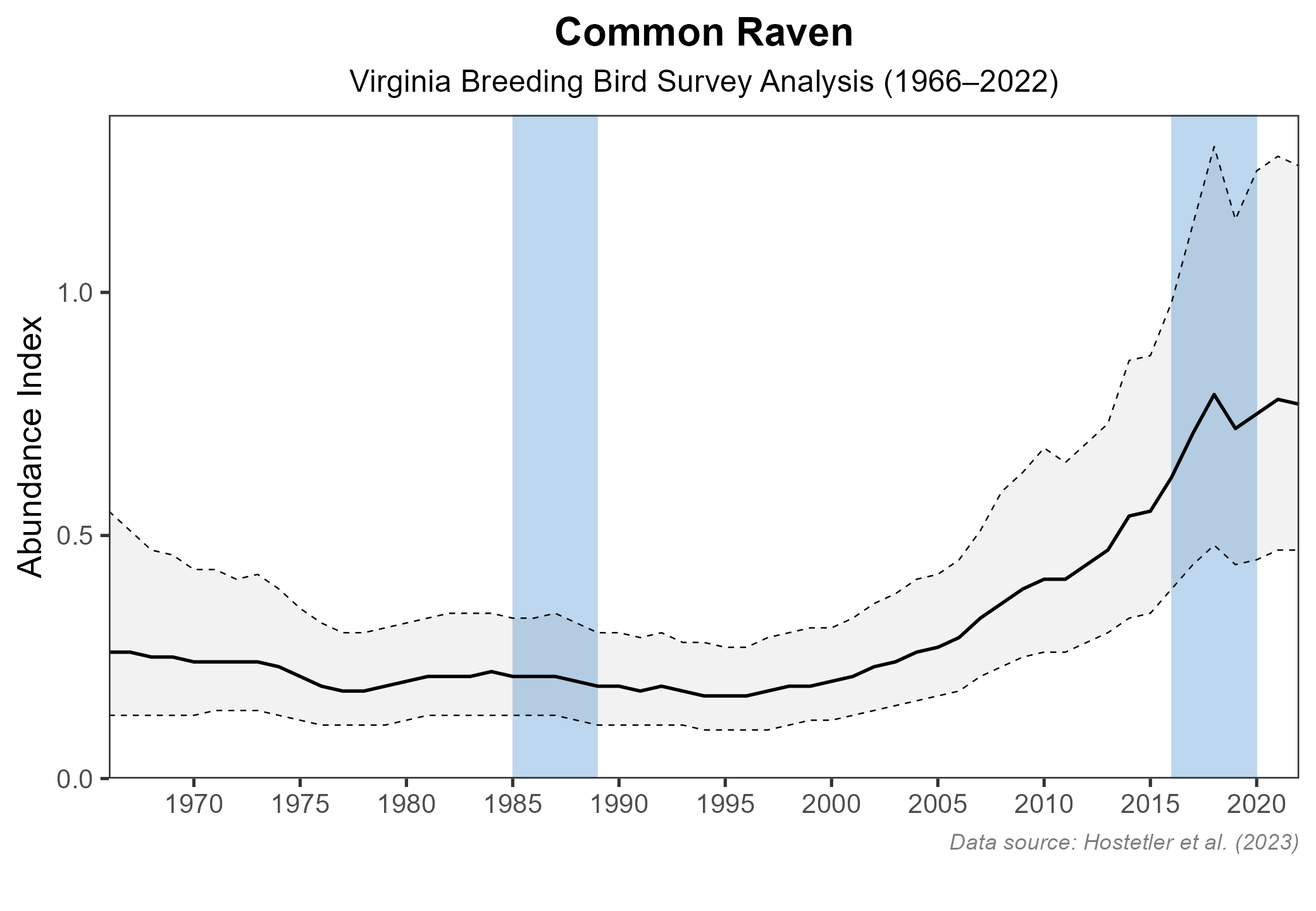

The total estimated Common Raven population in the state is approximately 28,000 individuals (with a range between 9,000 and 95,000). However, the abundance model was considered weak, hence the large confidence interval (see Analytical Methods). Population trends for the species are increasing in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data shows that the species experienced a significant increase of 2.13% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend for Virginia was even stronger, with a significant increase of 4.3% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Common Raven relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Common Raven population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Common Ravens are not currently the focus of any conservation efforts in Virginia. However, the species can be sensitive to human disturbance at the nest (Hooper 1977). Given its recent expansion into the urbanized I-95 corridor and densely populated areas of Northern Virginia, the Common Raven will likely face both opportunities and challenges as it spreads throughout the Commonwealth.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Boarman, W. I. and B. Heinrich (2020). Common Raven (Corvus corax), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.comrav.01.

Hackworth, Z. J., J. J. Cox, J. M. Felch, and M. D. Weegman (2019). A growing conspiracy: recolonization of Common Ravens (Corvus corax) in Central and Southern Appalachia, USA. Southeastern Naturalist 18:281–96. https://doi.org/10.1656/058.018.0208.

Hackworth, Z. J., J. M. Felch, S. M. Murphy, and J. J. Cox (2022). Detectability of Common Ravens (Corvus corax) in the Eastern USA: rapid assessment of a recolonizing species. Ecosphere 13:e4148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4148.

Hooper, R. G. (1977). Nesting habitat of Common Ravens in Virginia. The Wilson Bulletin 89:233–242.

Hooper, R. G., H. S. Crawford, D. R. Chamberlain, and R. F. Harlow (1975). Nesting density of Common Ravens in the Ridge-Valley Region of Virginia. American Birds 29:931–935.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.