Introduction

As the sun dips below the horizon in the Virginia countryside, residents are often treated to the call of a Chuck-will’s-Widow. In fact, with its loud, repetitive chuck-wills-widow, chuck-wills-widow, it is safe to say this species is among Virginia’s most vocal and identifiable nocturnal birds. Its small bill conceals a large mouth, which it uses to consume insects while flying low to the ground (Straight and Cooper 2020). A woodland bird, it tends to breed in slightly more open habitats than its close relative, the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus) (Straight and Cooper 2020).

Breeding Distribution

The Chuck-will’s-Widow is largely, but not completely, confined to areas east of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where it is most likely to be found in the central and southern Piedmont and the western Coastal Plain regions (limited data prevented development of a distribution model for the Mountains and Valleys region) (Figure 1). It is most likely to inhabit blocks with a diversity of habitat types, including open shrublands, grasslands, and forest edges. It is less likely to occur in areas with intensive agriculture, human development, or extensive forest cover.

Chuck-will’s-widow distribution during the First Atlas and the change between Atlas periods could not be modeled due to modeling limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Chuck-will’s-widow breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

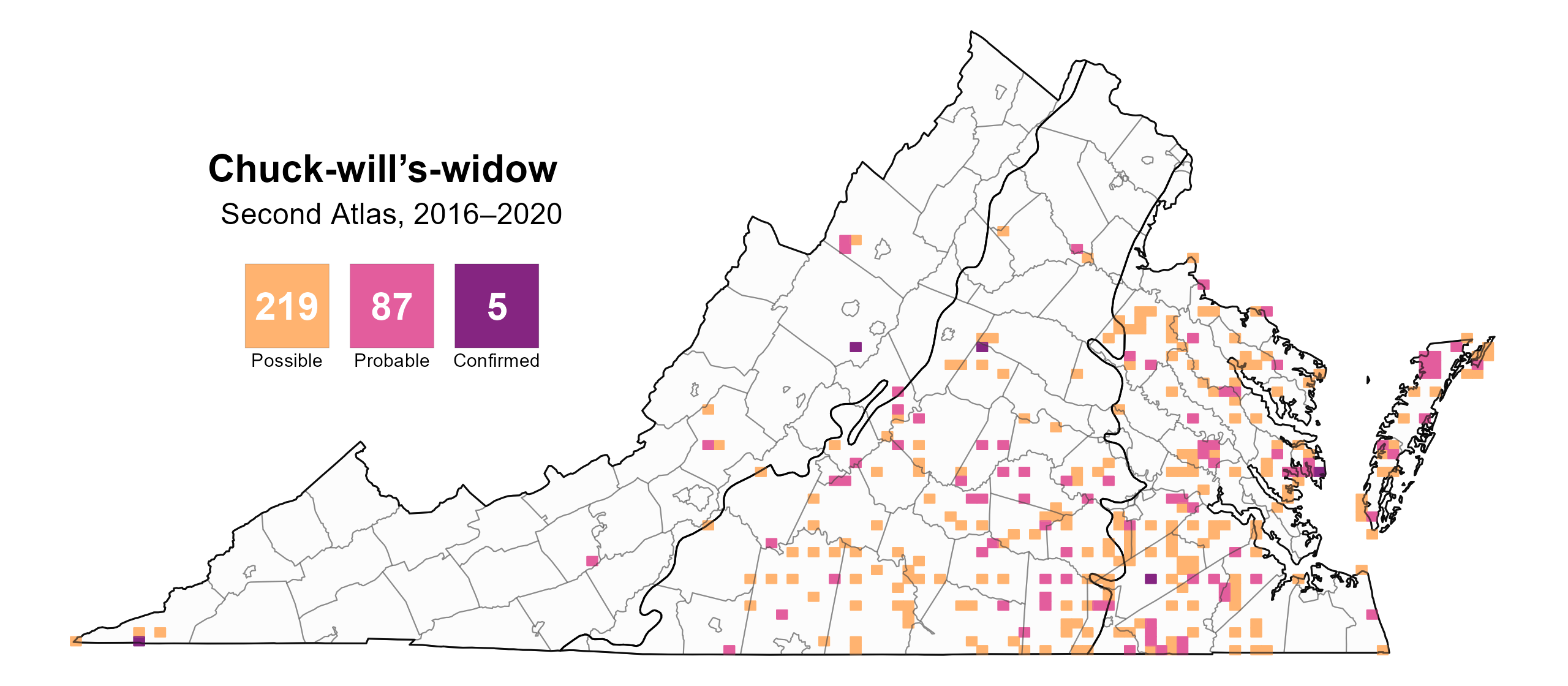

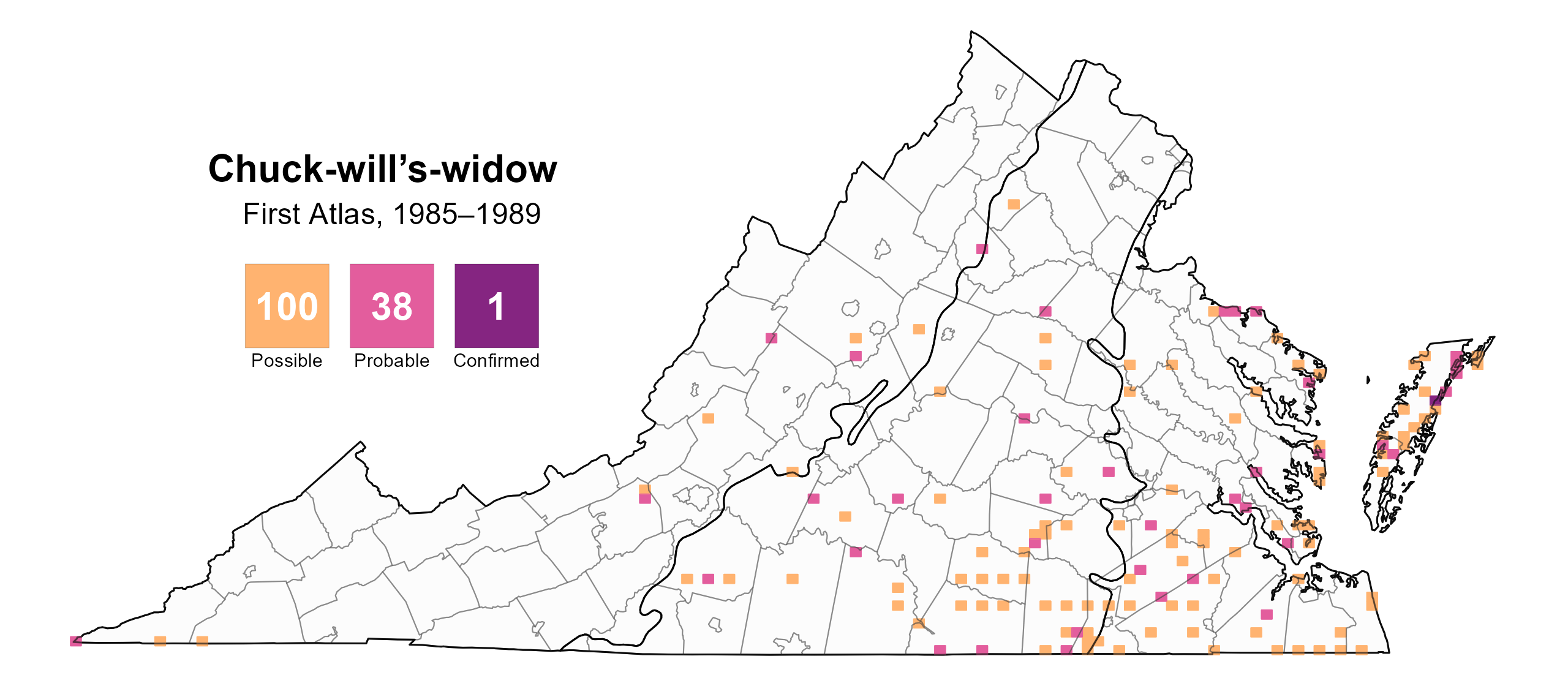

Chuck-will’s-Widow was a confirmed breeder in only five blocks and five counties (Augusta, Fluvanna, Lee, Mathews, and Sussex) across the state, and it was found to be a probable breeder in an additional 36 counties (Figure 2). Only 12 blocks with breeding evidence fall within the Mountains and Valleys region, where the species is considered locally uncommon to rare (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). The large difference in the number of blocks where breeding was confirmed versus probable was related to the Chuck-will’s-Widow’s nocturnal nature and well-camouflaged nests, which make it difficult to confirm breeding. The species was recorded in nearly three times as many blocks during the Second Atlas than during the First Atlas (Figure 3), despite its decreasing population trend (see Population Status section). This result is likely due to substantially greater survey effort during the Second Atlas.

As noted above, breeding was difficult to confirm with only five documented breeding observations. The earliest breeding confirmation is from early May when a distraction display was observed (Figure 4). Other breeding behaviors included observations of a nest with eggs (May 14), an occupied nest (June 9), and adults carrying food (June 21).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Chuck-will’s-widow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Chuck-will’s-widow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Chuck-will’s-widow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

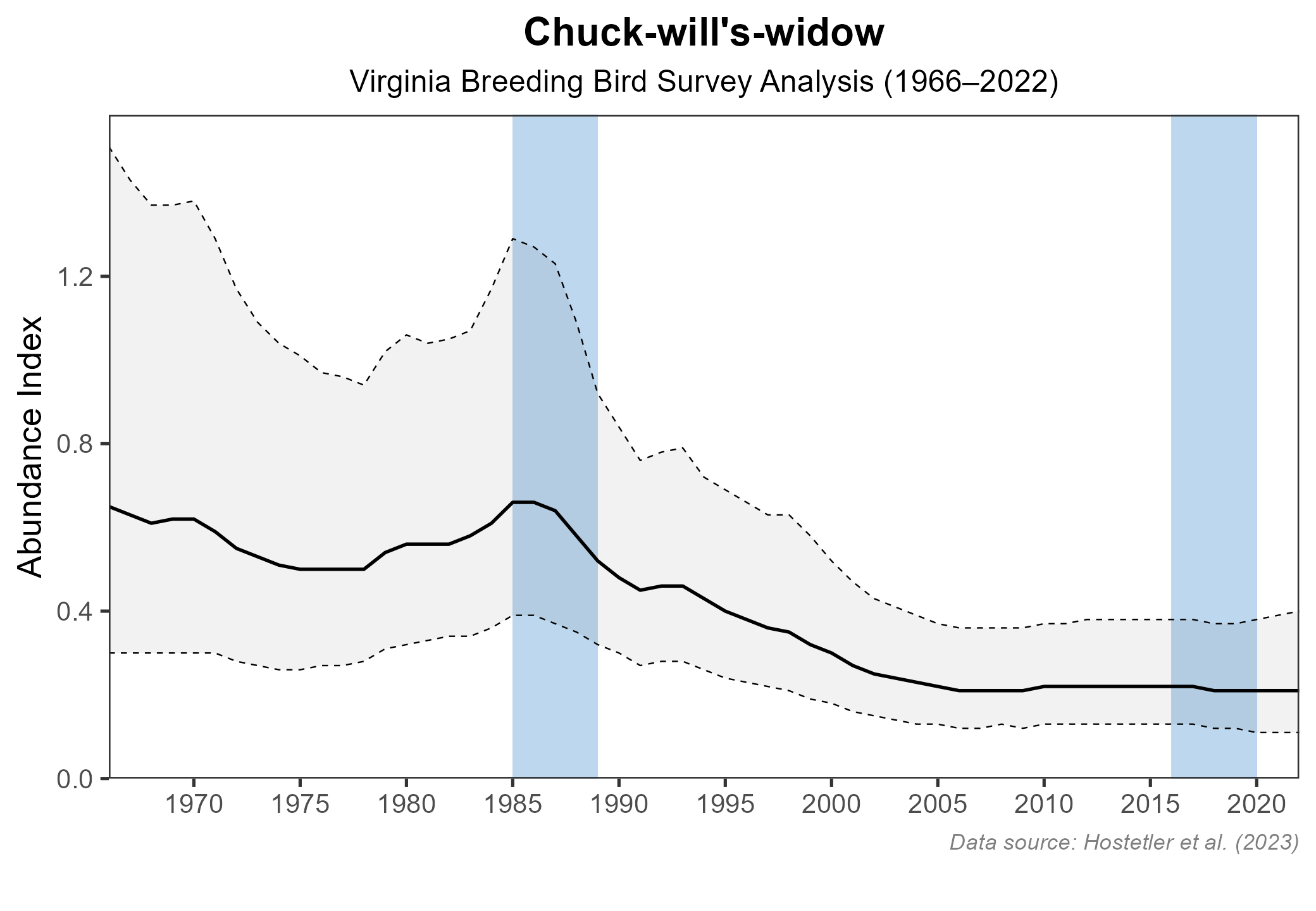

A low number of detections during Atlas point count surveys prevented the development of an abundance model for the Chuck-will’s-widow. Based on the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), the species’ population decreased by a significant 2.01% annually from 1966–2022 in Virginia, and the rate of decrease in the population between Atlas periods was even higher at a significant 3.52% per year from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5).

Figure 5: Chuck-will’s-widow population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Given the Chuck-will’s-widow’s decline in the state, the Virginia 2025 Wildlife Action Plan classifies it as a Tier III Species of Greatest Conservation Need, indicating it is of high conservation need (VDWR 2025). The reasons for this decline, which extends across its breeding range in the southeastern U.S., are not well understood for this poorly studied species.

A bird of forested systems, including open pine woods and mixed and deciduous forests (Straight and Cooper 2020), Chuck-will’s-widow requires open areas for foraging and cover for nesting and roosting (Tringali and Roberts 2024). In the absence of natural disturbances to forested habitats, it may benefit from timber management and prescribed fire to create these conditions (Tringali and Roberts 2024). Further studies are needed to better understand its habitat requirements and response to management. Outright habitat loss, direct mortality through collisions with vehicles and window strikes, and climate change impacts are additional threats whose role in the species’ population declines are undetermined (Tosa et al. 2025). Studies of insect prey availability and its impact on reproductive success are also needed. Renewed attention toward nightjars by the Atlantic Flyway Council may encourage collaborative studies to address some of these research needs.

The Nightjar Survey Network established by the Center for Conservation Biology at William and Mary in the mid-2000s (Wilson 2008) is being reinvigorated by the Maine Natural History Observatory and Birds Canada in collaboration with state wildlife agencies. This volunteer-based program will work to improve estimates of regional trends for the three eastern nightjar species.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Straight, C. A. and R. J. Cooper (2020). Chuck-will’s-widow (Antrostomus carolinensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.chwwid.01.

Tosa, M. I., A. J. Roberts, A. K. Tegeler, P. K. Devers, L. A. M. Parker, P. D. Hunt, B. D. Watts, M. Huang, A. C. Vitz, S. H. Schweitzer, et al. (2025). Design of a monitoring program to advance nightjar conservation along the Atlantic Flyway. Wildlife Society Bulletin e1581. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.1581.

Tringali, A. and T. Roberts. 2024. Nightjars in the Atlantic Flyway: Gap analysis, habitat associations, and best management practices. Atlantic Flyway Council. 11 pp.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M. D. (2008). The Nightjar survey network: program construction and 2007 Southeastern Nightjar survey results. CCBTR-08-01. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 11 pp.