Introduction

The Cedar Waxwing is a handsome bird with a muted color palette and is distinguished by its highly frugivorous (fruit-eating) diet. This species, named for the red wax tips of its secondary feathers, is easily located through the soft hisses of a whistling flock stripping berries from an ornamental plant. In fact, the Cedar Waxwing exhibits such a strong preference for fruit that Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) nest parasites have not been documented surviving in a waxwing nest, as the high-fruit content diet provided to waxwing nestlings is fatal to cowbirds (Rothstein 1976; Witmer et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

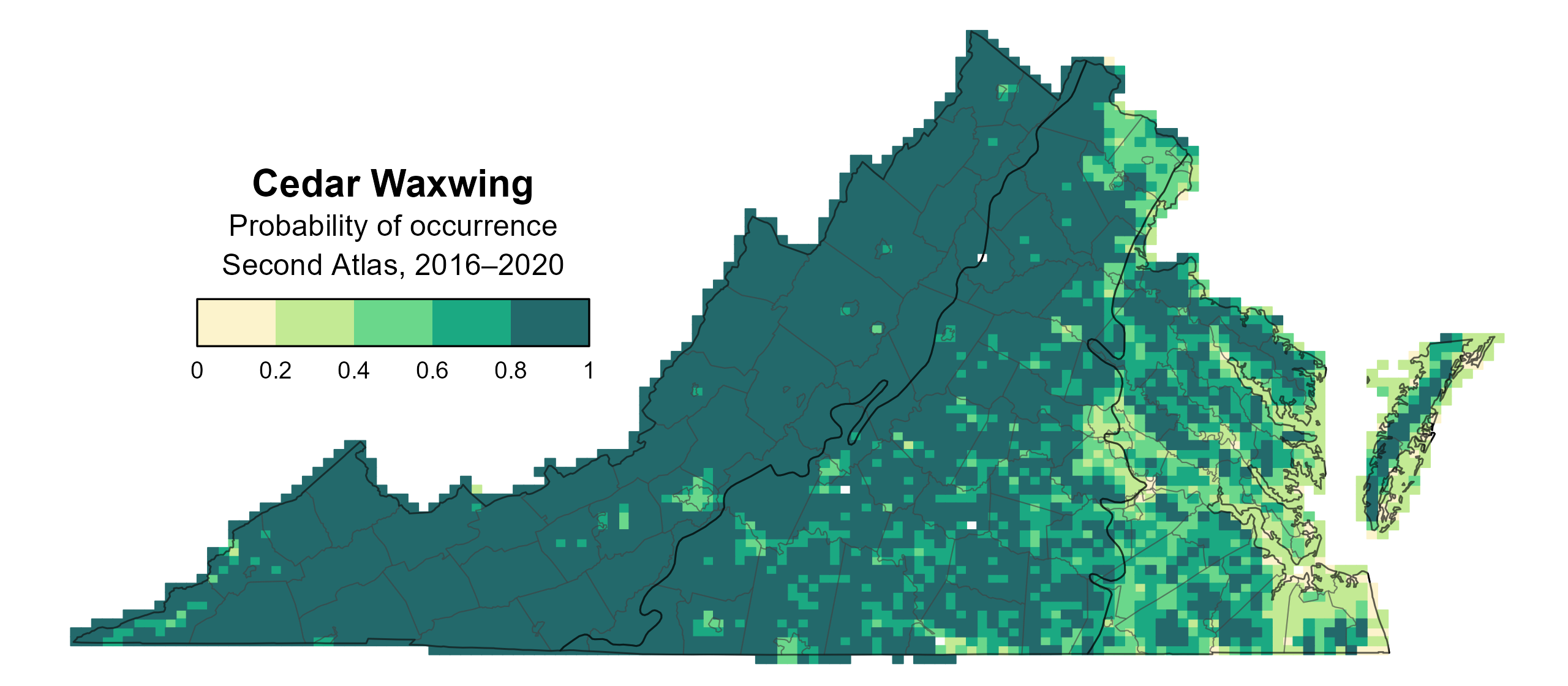

Virginia is near the southern extent of the Cedar Waxwing’s breeding range, but this species occurs in all three regions. It is most likely to occur in the Mountains and Valleys and northern Piedmont, particularly along the Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 1). However, this species is predicted to be absent as a breeder from the Hampton Roads area and some patches in the southern Piedmont region.

The likelihood of Cedar Waxwing occurrence increases with the proportion of forest and agricultural cover in a block. These habitat types are likely to contain sufficient fruiting plants, which the species often breeds near (Witmer et al. 2020). They are also slightly more likely to occur where there are larger forest patches, while they are less likely to occur in blocks with many different habitat types.

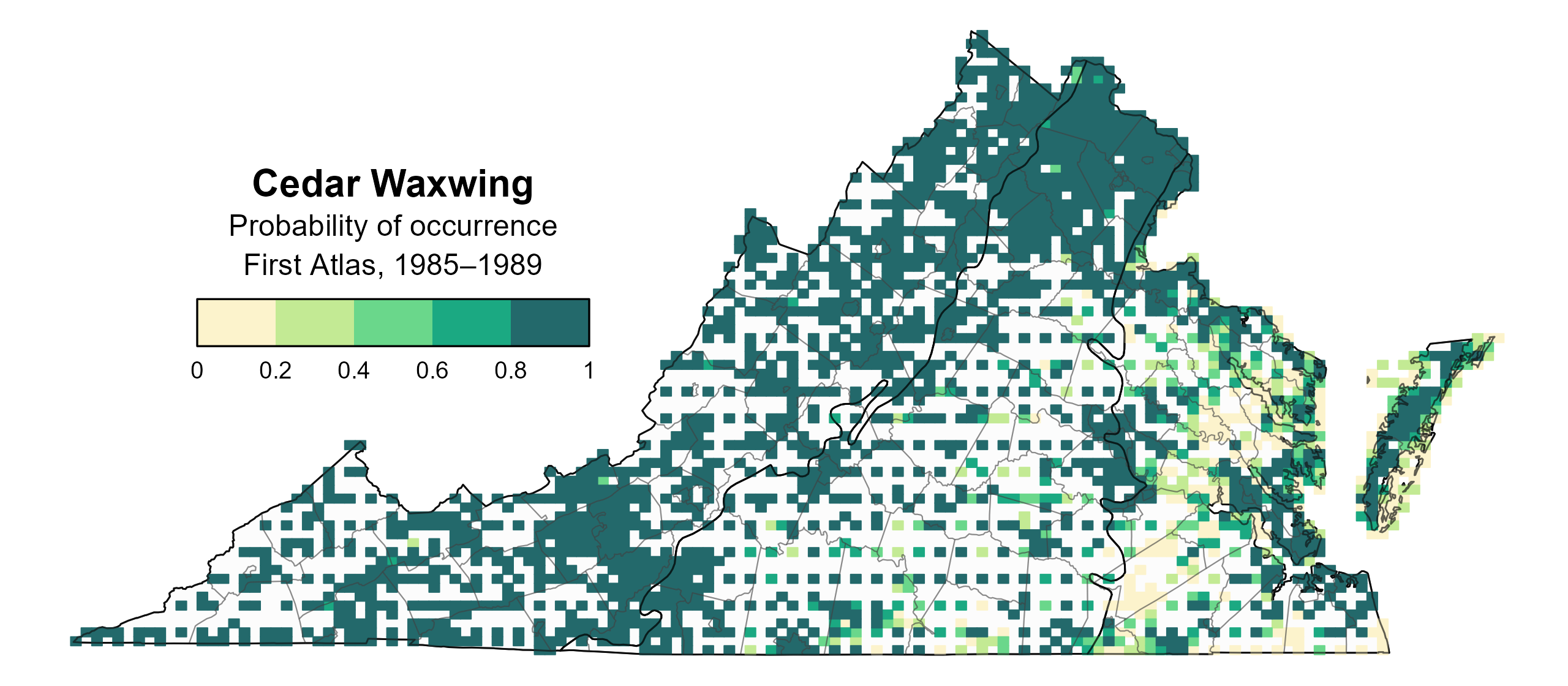

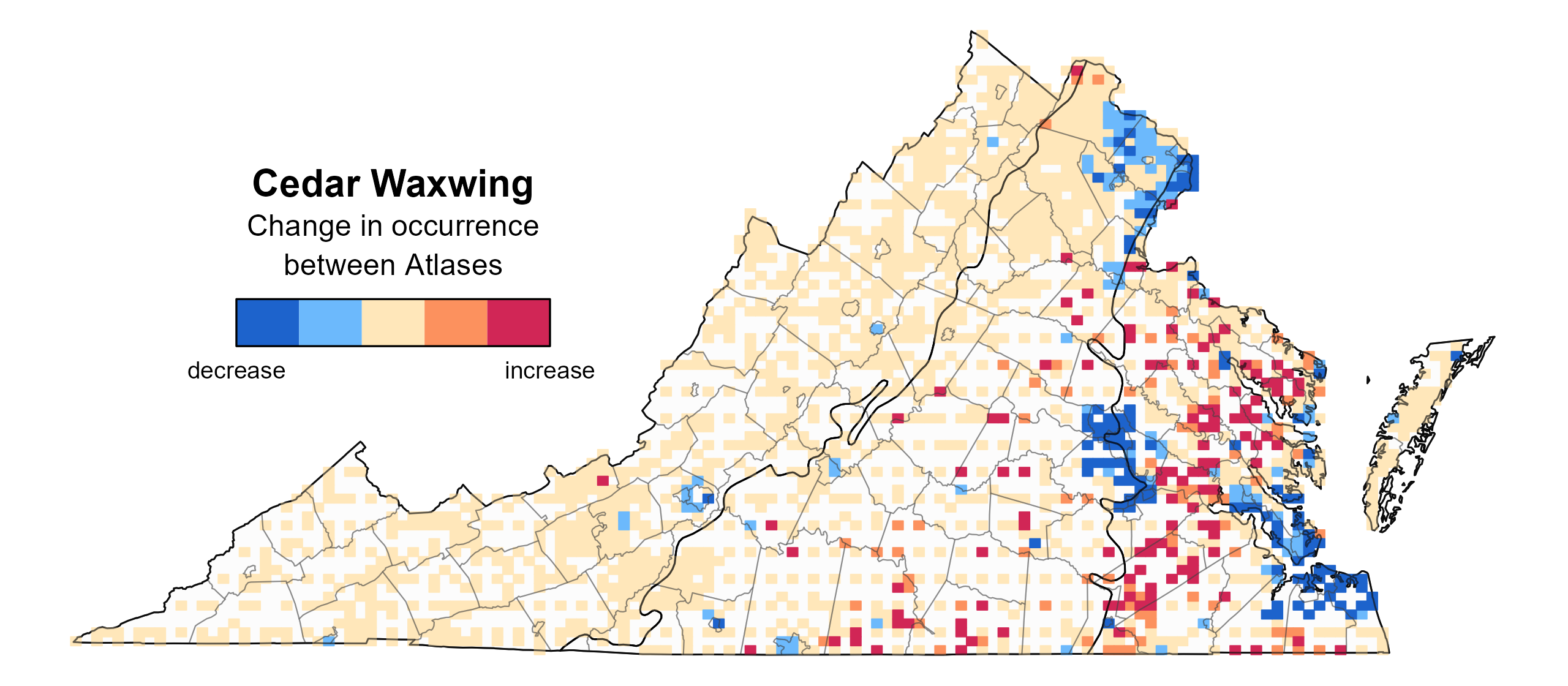

The Cedar Waxwing’s likelihood of occurring in the Second Atlas was mostly like that in the First Atlas (Figures 1 to 3). However, its probable occurrence decreased in urbanized areas such as Northern Virginia, the greater Richmond area, and the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area, while it increased in some areas of the Coastal Plain region. Otherwise, it was stable throughout the remainder of the state.

Figure 1: Cedar Waxwing breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Cedar Waxwing breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Cedar Waxwing change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

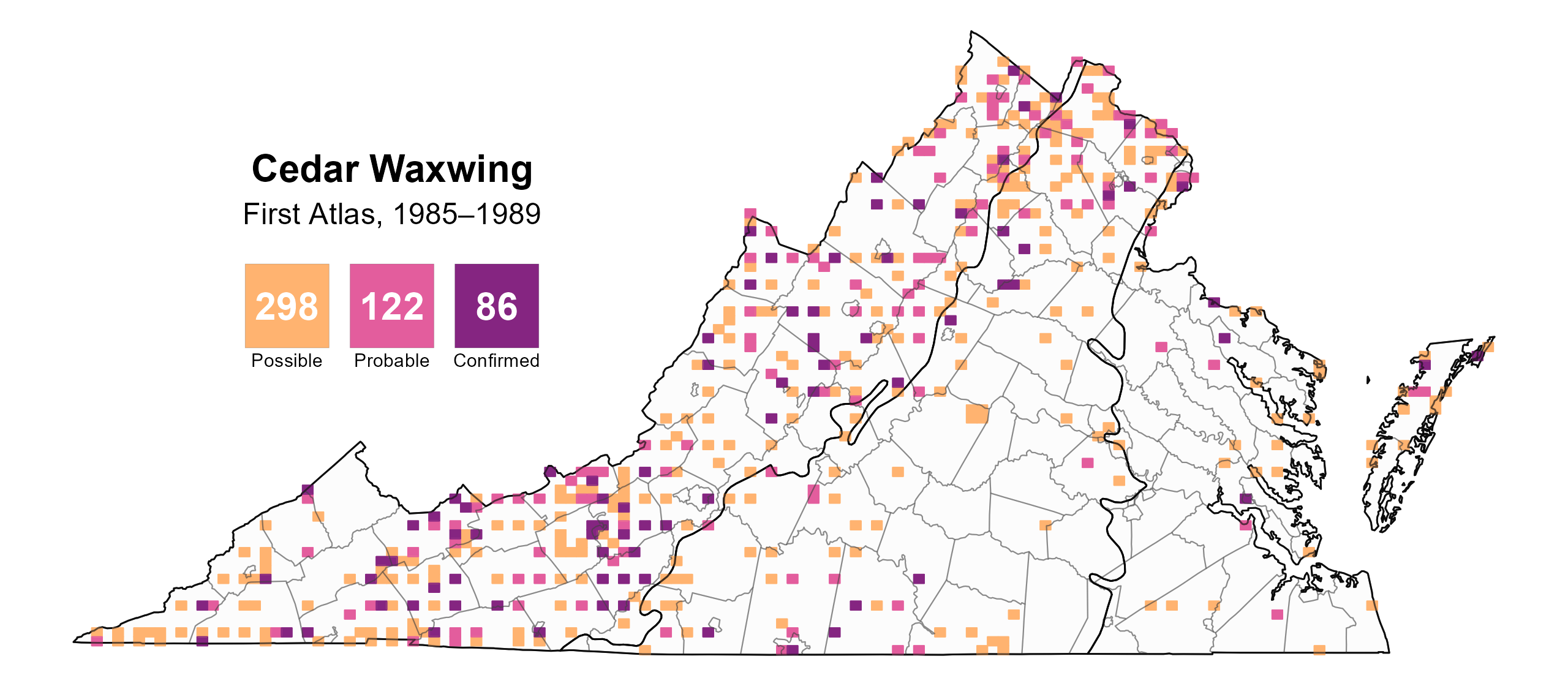

Cedar Waxwings were confirmed breeders in 276 blocks and 83 counties and probable breeders in an additional four counties (Figure 4). Cedar Waxwings were confirmed breeders in all regions of the state during both Atlas periods (Figures 4 and 5), although more confirmations were recorded during the Second Atlas.

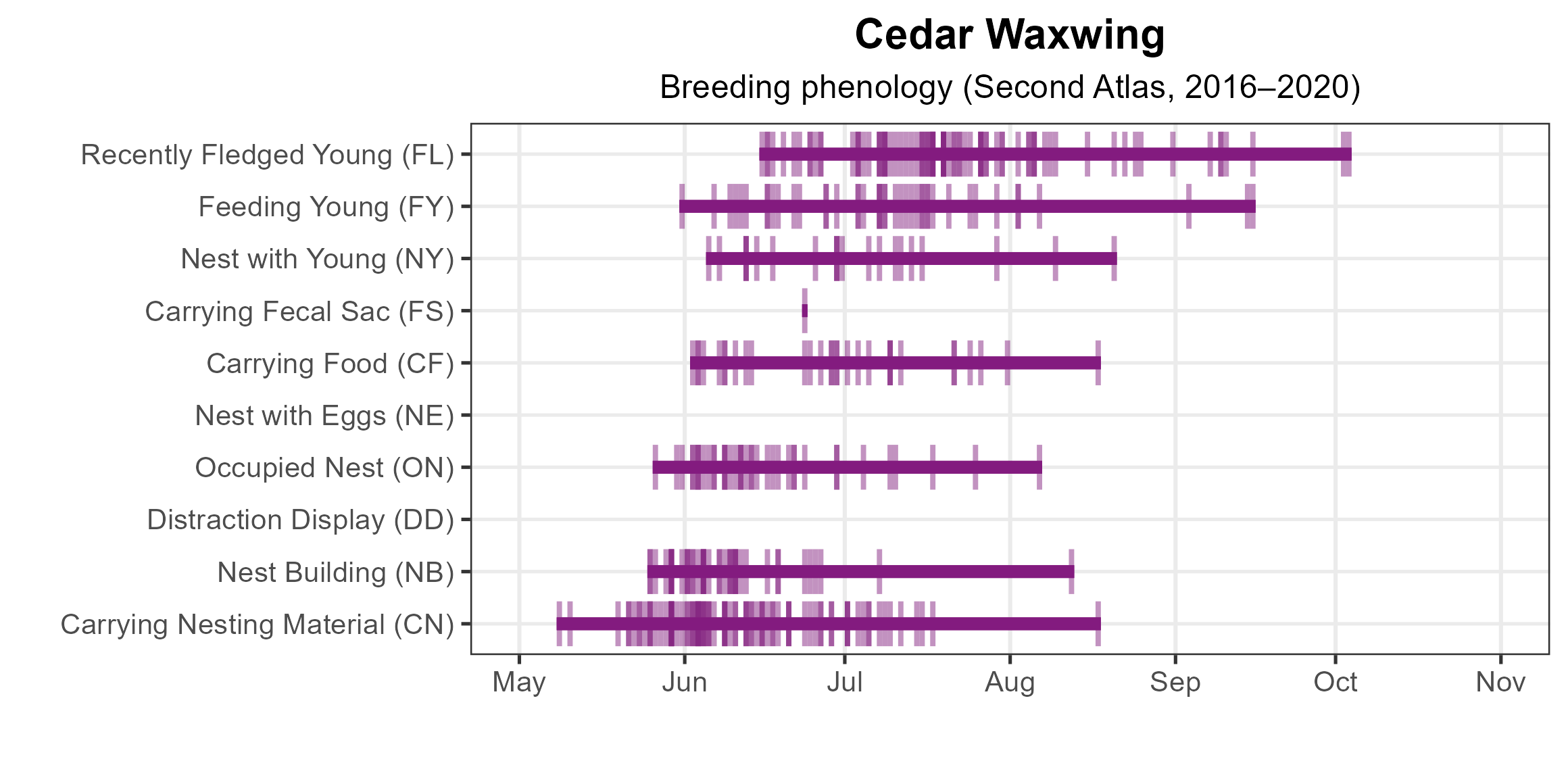

Nest building began in May, with birds observed carrying nesting material starting on May 8 (Figure 6). Breeding was confirmed from May 26 (occupied nest) through October 3 (recently fledged young). These exceptionally late records came from Grayson and Bedford Counties and may represent second broods. Cedar Waxwings nest later than most North American songbirds, switching from fruit to arthropod prey from May to late summer, when new fruit crops begin to ripen (Witmer et al. 2020).

For more general information on the breeding habits of the Cedar Waxwing, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Cedar Waxwing breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Cedar Waxwing breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Cedar Waxwing phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

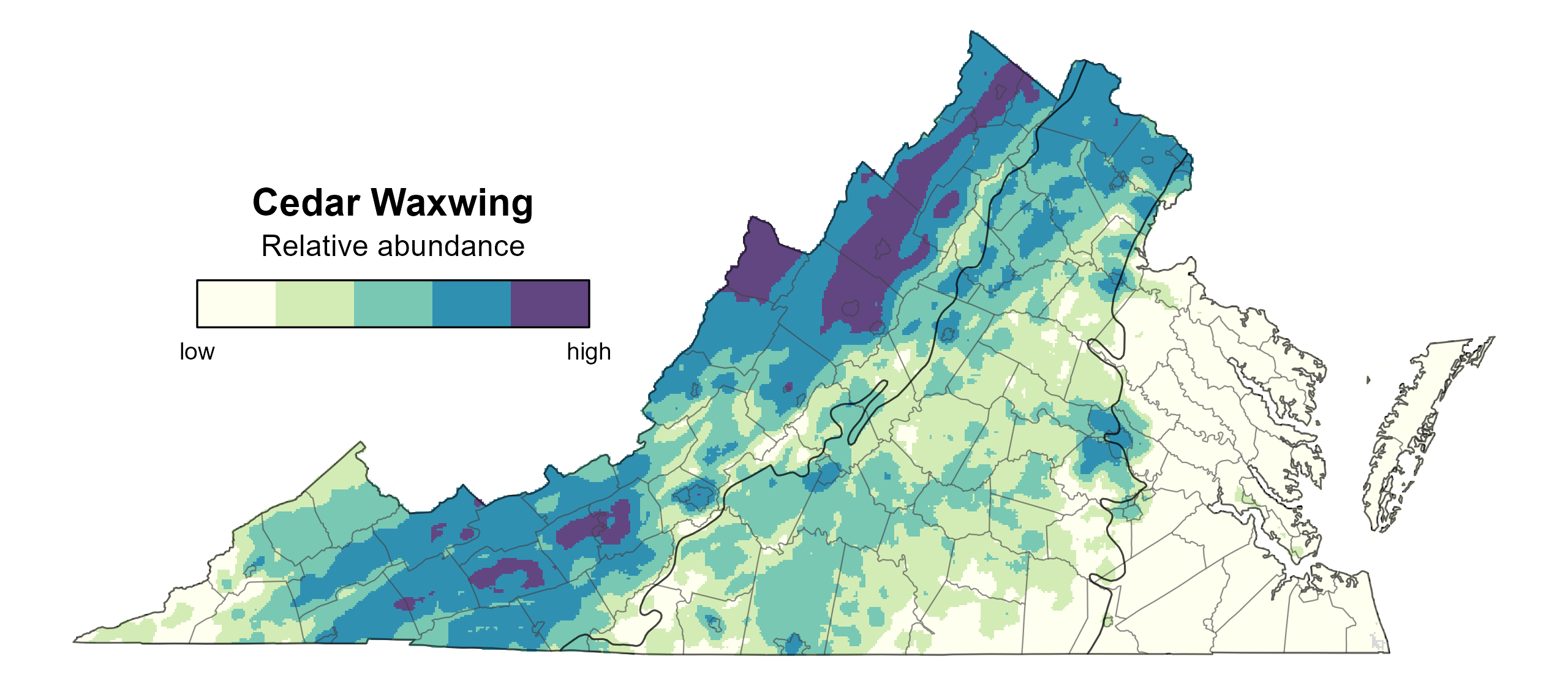

Cedar Waxwing relative abundance was estimated to be highest west of the Blue Ridge mountains in the Shenandoah Valley and southwestern Virginia (Figure 7). Abundance was lowest in the Coastal Plain region.

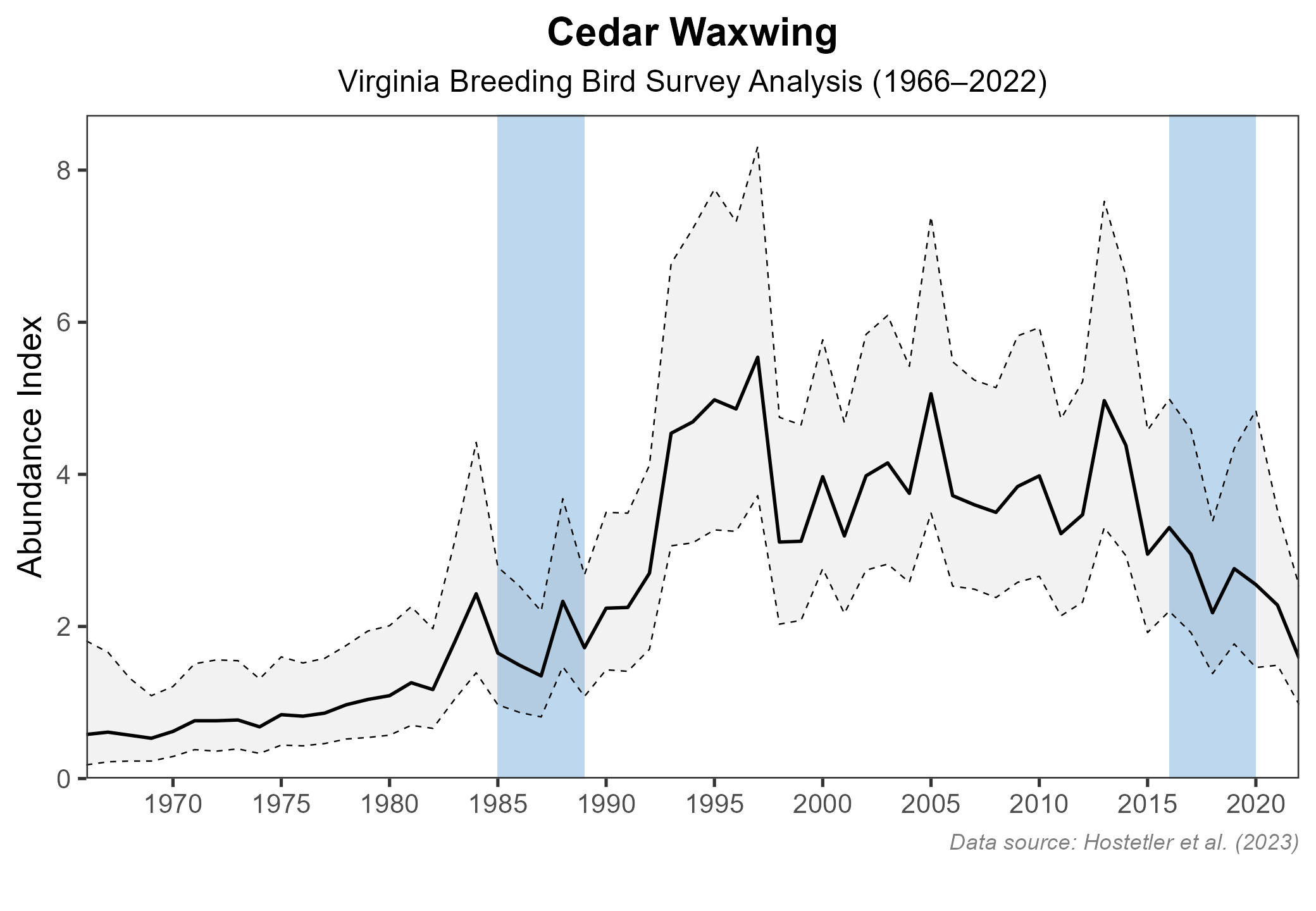

The total estimated Cedar Waxwing population in the state is approximately 1,255,000 individuals (with a range between 797,000 and 1,976,000). However, the abundance model was considered weak, hence the large confidence interval (see Analytical Methods). The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) population trend for Virginia showed a nonsignificant increase of 1.75% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend for Virginia showed a nonsignificant increase of 1.55% per year from 1987–2018. Because of the species’ nomadic nature and late breeding season, Cedar Waxwings are inconsistent on BBS surveys as seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Cedar Waxwing relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Cedar Waxwing population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because Cedar Waxwing populations are stable, the species is not the focus of any specific conservation efforts in Virginia. Despite their stability at the population level, individual Cedar Waxwings are at risk of collisions with human structures and vehicles when large flocks gather in ornamental plants near buildings and roadways. They are also vulnerable to intoxication and poisoning from fermenting fruit and pesticides (Witmer et al. 2020). Nonetheless, the high availability of fruiting trees and suitable habitat indicate the Cedar Waxwing is secure in Virginia, allowing them to continue their important role as seed-dispersers for plants (Meyer and Witmer 1998).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Meyer, G. A., and M. C. Witmer (1998). Influence of seed processing by frugivorous birds on germination success of three North American shrubs. The American Midland Naturalist 140:129-139. https://doi.org/10.1674/0003-0031(1998)140[0129:IOSPBF]2.0.CO;2.

Rothstein, S. I. (1976a). Cowbird parasitism of the Cedar Waxwing and its evolutionary implications. The Auk 93:498-509.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Witmer, M. C., D. J. Mountjoy, and L. Elliott (2020). Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.cedwax.01.