Introduction

If you are lucky enough to witness it, one of nature’s most spectacular sights is seeing a brood of Wood Duck fledglings leap, one after another, from their nesting cavity, which can be up to 50 ft (15 m) high in a tree. After bouncing their way to a safe landing, the young, still flightless birds, follow their mother up to 5 mi (8 km) to reach water (Hep and Bellrose 2020).

With their iridescent green and chestnut plumage framed by bold white stripes, male Wood Ducks are considered among the most beautiful of Virginia’s birds. In general, Wood Ducks can be found throughout the state in areas with bottomland forests, wooded swamps, freshwater marshes, and beaver ponds. They are also common along forested creeks and rivers. Wood ducks will use man-made nest boxes placed in appropriate wetland habitats and can be a joy to watch during the breeding season.

Breeding Distribution

During the Second Breeding Bird Atlas, model limitations prevented development of distribution models for Wood Ducks (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For information on where they occur in the state, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

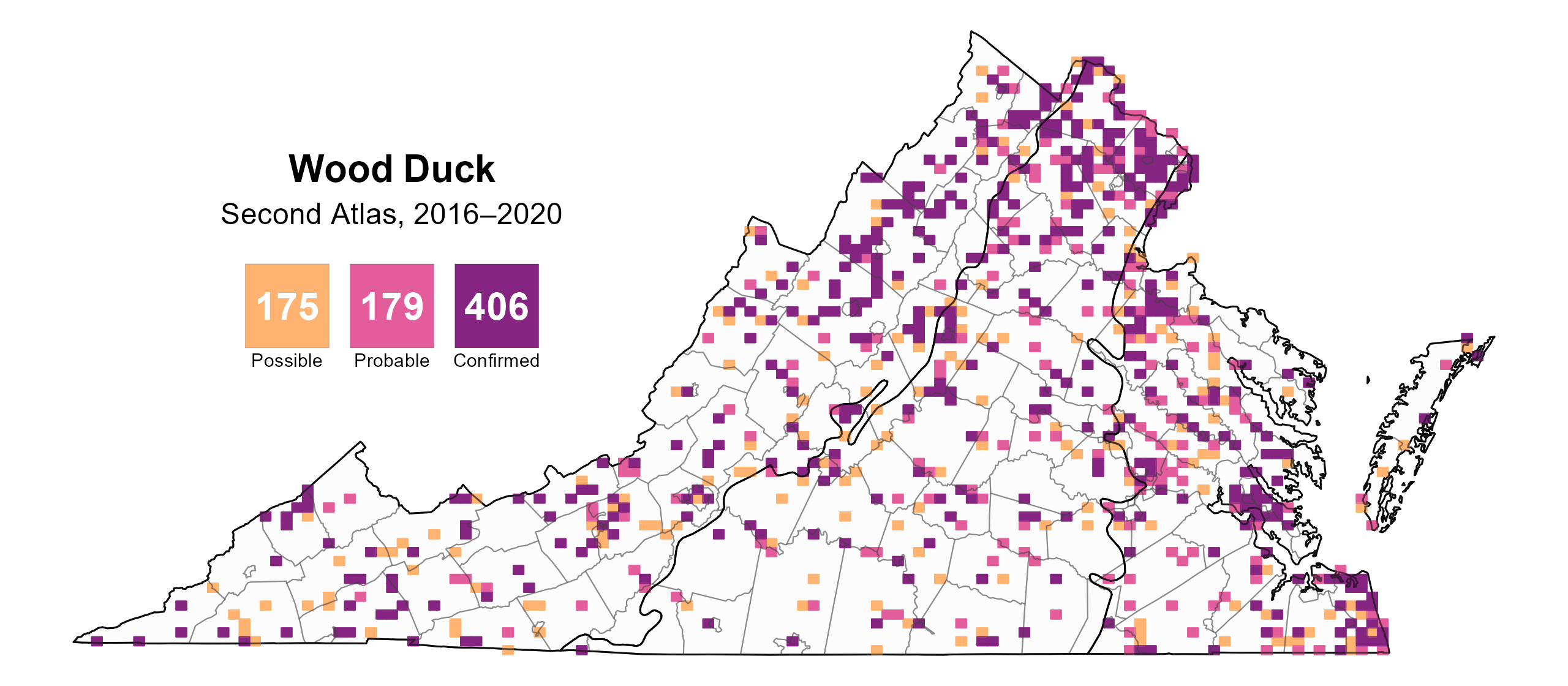

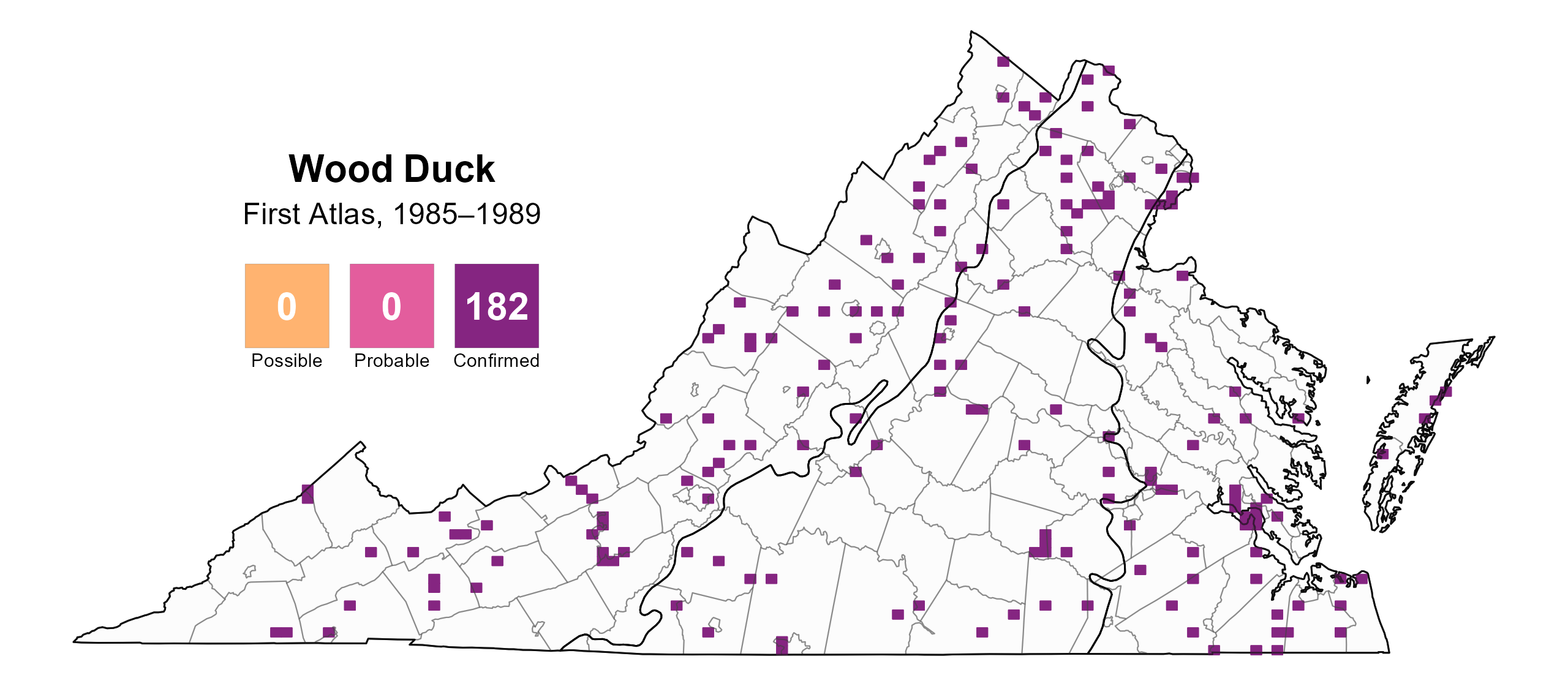

Wood Ducks were confirmed breeders in 406 blocks and 108 counties and considered to be probable breeders in an additional six counties (Figure 1). While Wood Ducks were confirmed breeders in all regions of the state, the highest concentrations of breeding activity were observed within the eastern Coastal Plain’s system of rivers, marshes, and estuaries and in the northern Piedmont region, especially in Fairfax, Fauquier, and Loudon Counties. Fewer breeding observations were recorded during the First Atlas, though this may have been due to the difference in survey effort between Atlases (Figure 2).

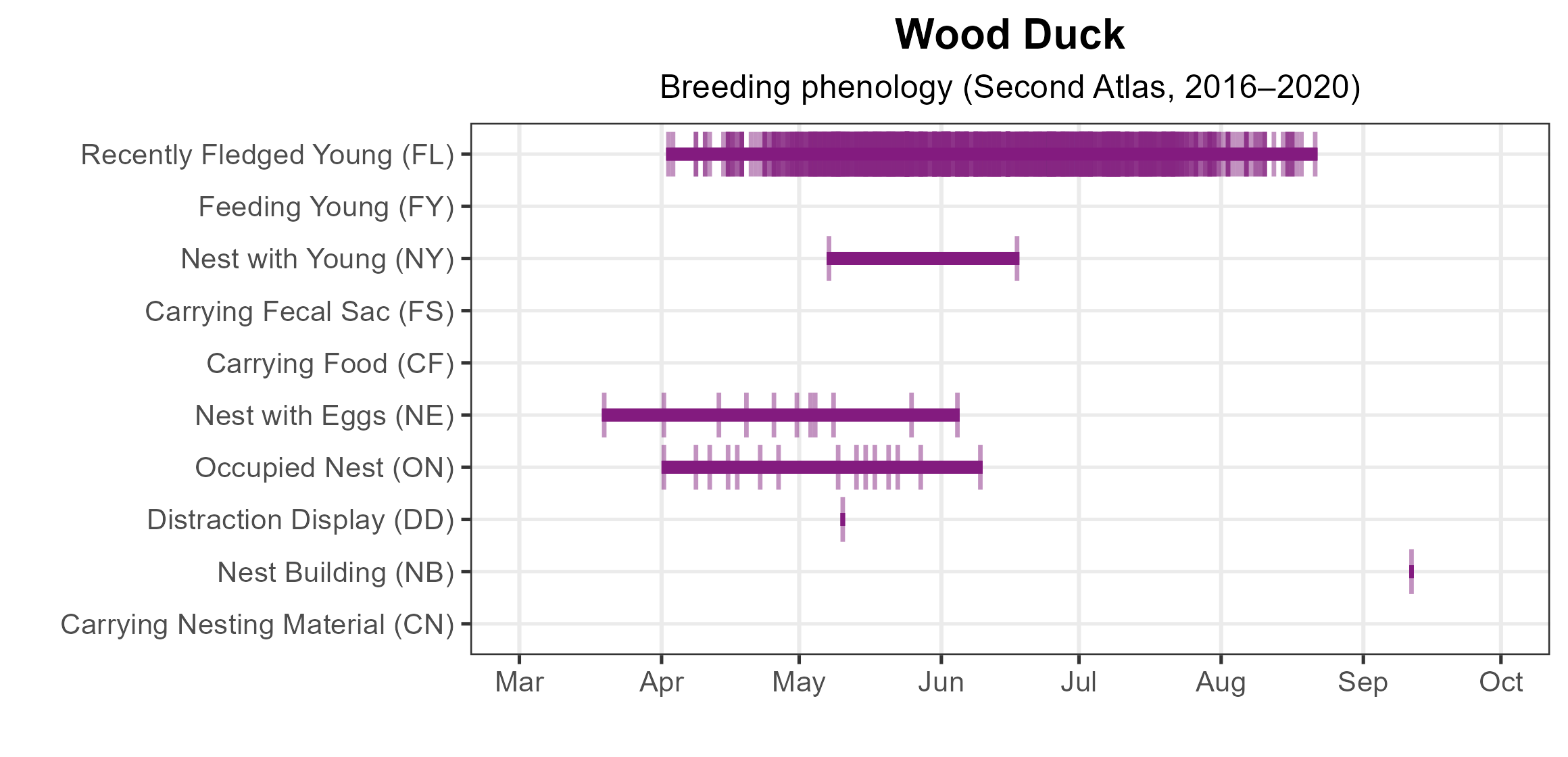

The earliest signs of breeding were recorded in mid-March by observing nests with eggs, and nests with young were observed through June 17 (Figure 3). The latest breeding activity observed was nest building in early September, but observations of recently fledged young were the most frequently documented breeding behavior.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Wood Duck breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Wood Duck breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Wood Duck phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Atlantic Flyway Breeding Waterfowl Plot Survey 1993–2019 showed an increasing Wood Duck population trend during that period (Roberts 2019), indicating that the declines in the 1930s and 1940s have been reversed by cooperative management programs including wetland habitat enhancements and nest box programs (Gary Costanzo, personal communication).

Conservation

Wood Ducks in Virginia, and throughout their range, declined precipitously from the late 1800s through the 1950s because of commercial hunting and removal of large cavity trees that are required for successful nesting. Regulated hunting and the use of artificial nesting boxes have helped restore populations (Costanzo and Hindman 2007). Information on how to build and place Wood Duck nesting boxes can be found at the Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative website, and nesting data can be submitted to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s NestWatch program. Finally, although their numbers have rebounded, increases in human development and loss of forested wetlands could threaten their populations in the region (Costanzo and Hindman 2007).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Costanzo, G. R., and L. J. Hindman (2007). Chesapeake Bay breeding waterfowl populations. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 30:17–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25148273.

Hepp, G. R. and F. C. Bellrose (2020). Wood Duck (Aix sponsa), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wooduc.01.

Roberts, A. (2019). Atlantic Flyway breeding waterfowl plot survey, 2019. https://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/documents/2019_afc_plotsurvey.pdf.