Introduction

The Wild Turkey is one of the most recognizable birds in Virginia and the U.S., as they are found in every state but Alaska. It is the only large, mostly ground-dwelling gamebird in the state. In fact, it rarely flies, and when it does, it does not go far (McRoberts et al. 2020). Wild Turkeys inhabit forests stands that can range in age; however, for breeding, they often nest in younger forests that provide thick herbaceous and shrub cover or in old fields and pastures or newly cut timber stands (VDWR 2025).

The species has an interesting history and is often utilized as an example of conservation success (McRoberts et al. 2020). By the early 1900s, it was estimated that Wild Turkeys no longer occurred in two-thirds of the Commonwealth, owing to habitat loss and market hunting (VDWR 2025). However, due to extensive restocking and management efforts, its population rebounded, and today, they are found across the state (for more information on conservation efforts, see Conservation section).

Breeding Distribution

During the Second Virginia Breeding Bird Atlas, a distribution model for the Wild Turkey could not be developed due to modeling limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

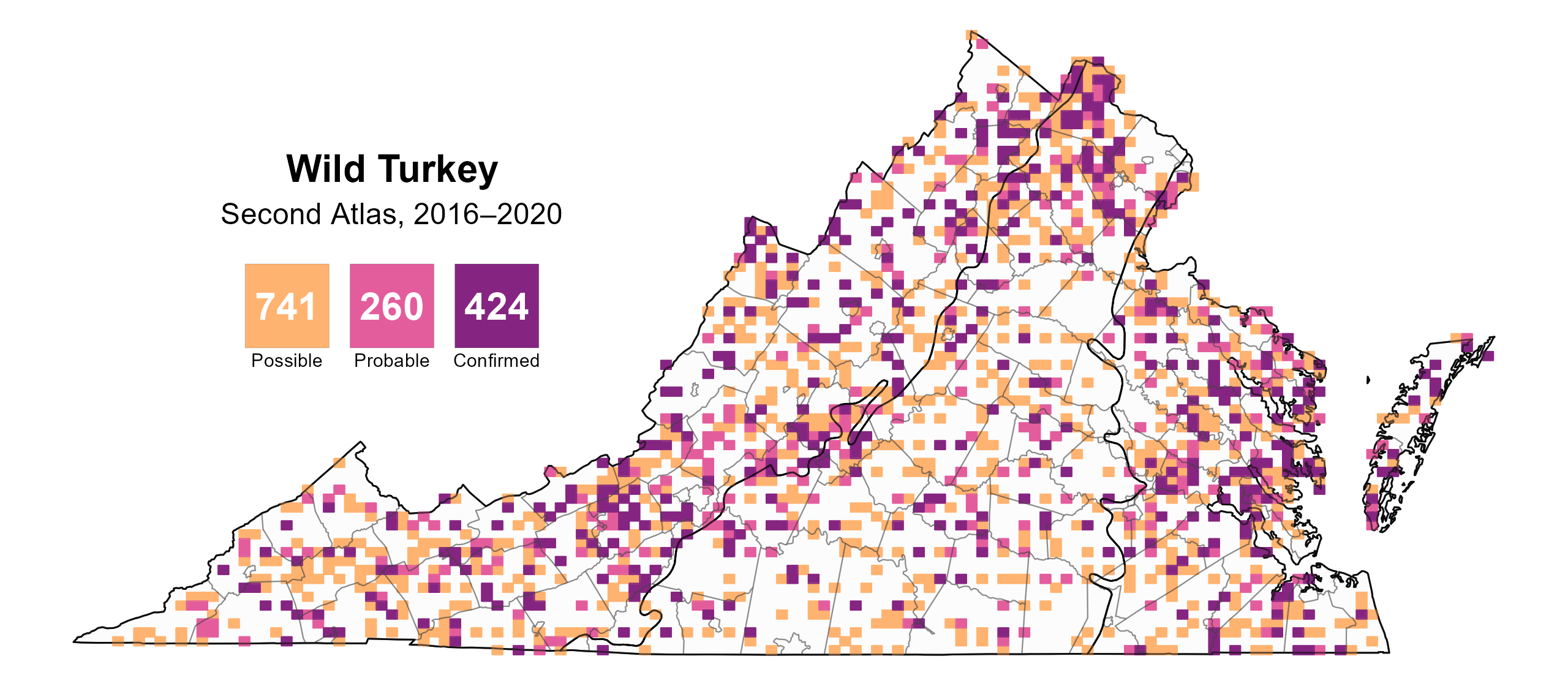

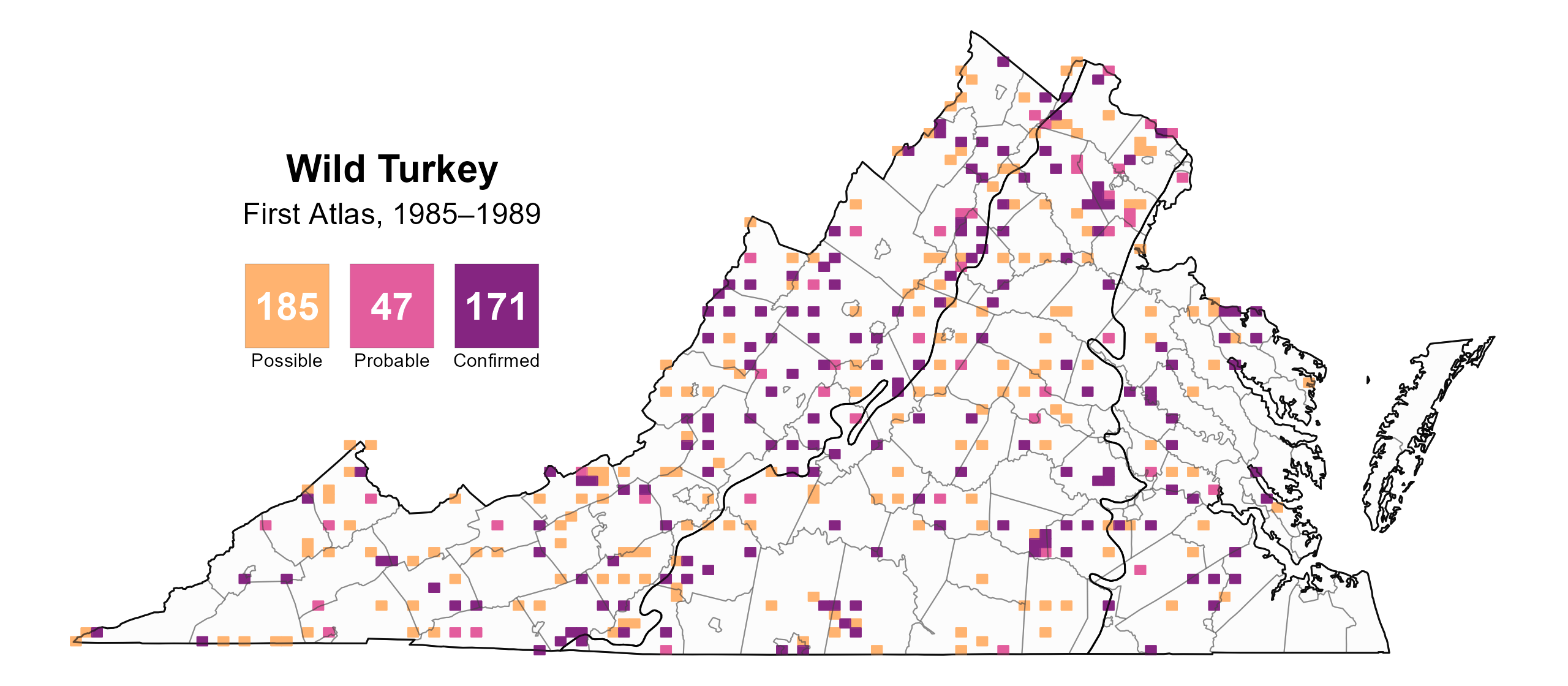

Wild Turkeys were confirmed breeders in 424 blocks and 95 counties and found to be probable breeders in an additional nine counties (Figure 1). They were detected throughout the state during the First Atlas as well (Figure 2). However, fewer confirmed breeders were observed during the First Atlas than during the Second Atlas. This result was likely due to increased effort during the Second Atlas as well as its population increase in the state (see Population Status).

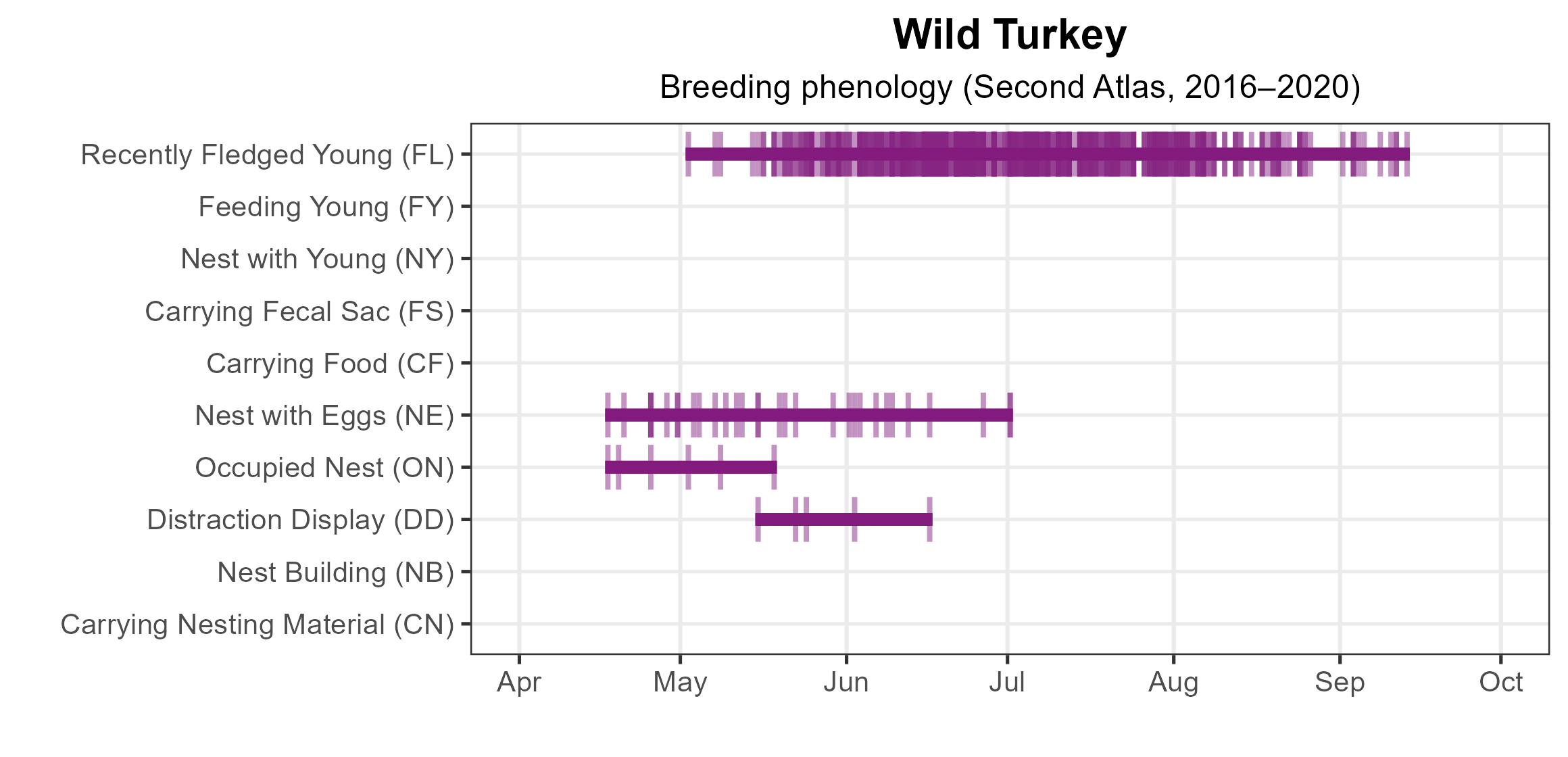

The earliest confirmed breeding behavior was documented in early April when occupied nests (April 17 – May 18) and nests with eggs (April 17 – July 1) were observed (Figure 3). Breeding was primarily confirmed through observations of recently fledged young (May 2 – September 13). For more information about the breeding phenology of this species, please see All About Birds.

Figure 1: Wild Turkey breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Wild Turkey breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Wild Turkey phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

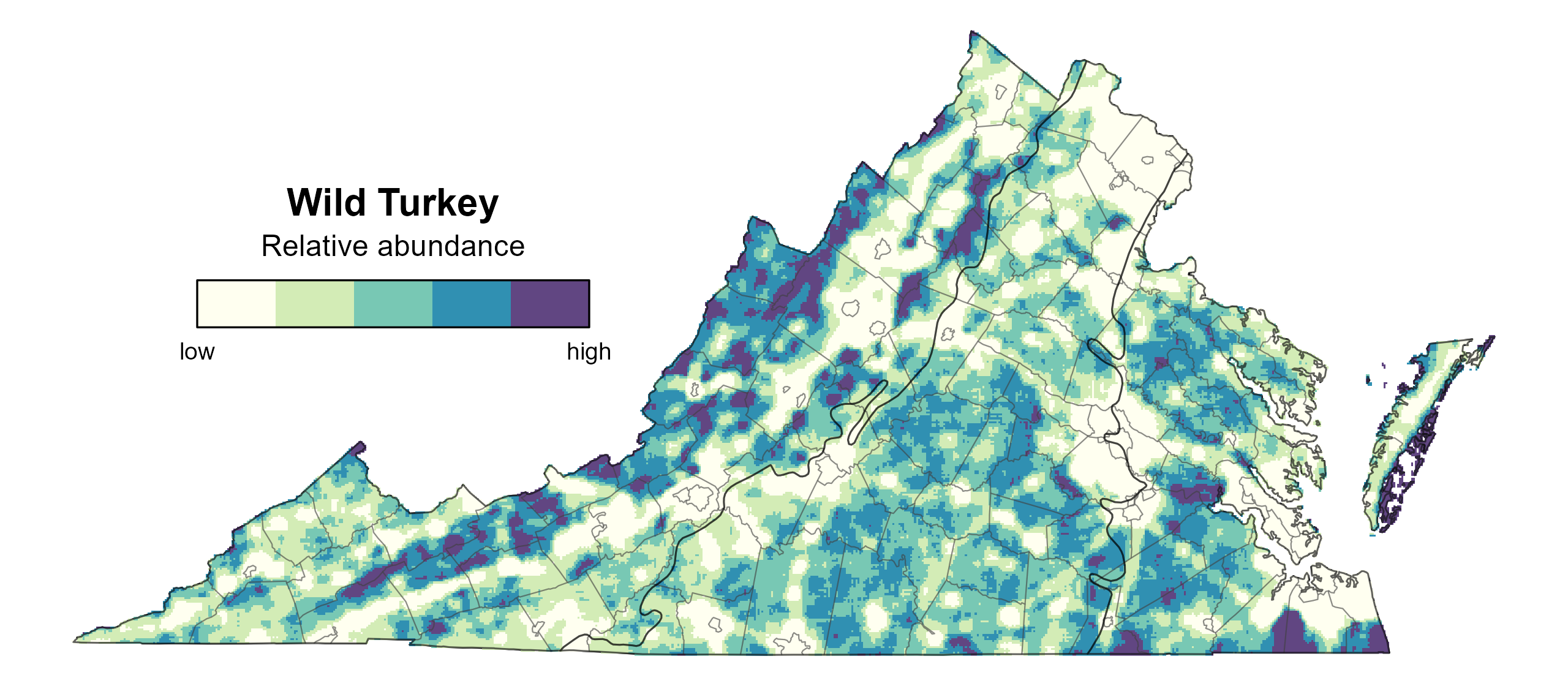

Wild Turkey relative abundance was estimated to be moderate to high across much of the state except for large urban areas, such as Northern Virginia, Richmond, and the Norfolk-Hampton Roads area, and the valleys of the Mountains and Valley region (Figure 3).

The total estimated Wild Turkey population in Virginia is approximately 57,000 individuals (with a range between 22,000 and 147,000). Trend data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) for Virginia show the Wild Turkey population experienced a significant annual increase of 4.62% from 1966–2022, and between Atlas periods, the population grew by an average of 5.35% per year from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Wild Turkey relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 5: Wild Turkey population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The first step toward conservation of turkeys in Virginia was passage of the 1912 “Robin Bill,” which prohibited the sale of turkeys and other wildlife species. The restoration of Virginia’s turkey population began in 1929 with the introduction of game farmed turkeys. From 1929 to 1960, biologists with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) stocked over 21,000 turkeys across Virginia; however, most of these stockings did not produce meaningful populations. It was not until 1955 when the VDWR began capturing wild turkeys from established populations to restock in other locations that populations began to thrive (VDWR 2025). Virginia’s turkey population was considered fully restored after successful stockings on Virginia’s Eastern Shore in 1993.

Today, management and conservation of wild turkey in Virginia is guided by a management plan developed and implemented through the VDWR (VDWR 2025). Regulated hunting of wild turkeys allows use of the resource while ensuring long-term viability of the population, and hunting-focused conservation organizations conduct multiple management activities focused on Wild Turkey.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

McRoberts, J. T., M. C. Wallace, and S. W. Eaton (2020). Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wiltur.01.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia Wild Turkey management plan (2025-2034). Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA.