Introduction

Royal Terns are among the most abundant large terns in Virginia, second only to Caspian Terns (Hydroprogne caspia) in size. Their striking black crests and bright orange bills make them a conspicuous presence along the coast and around the Chesapeake Bay. Though their nesting colonies are few, they exhibit extremely high densities (Buckley et al. 2021). These colonies are a cacophonous din, with the Royal Tern’s keerik call being one of the loudest voices. Shortly after hatching, juveniles move into crèches with other Royal and Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis), where they are attended by their parents (Buckley et al. 2021).

Breeding Distribution

The Royal Tern was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Royal Tern only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Given the breeding biology of the species, the Royal Tern is unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Confirmation of breeding was based on records generated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

Royal Terns were confirmed breeders in 5 blocks (Figure 1). The species breeds on Smith Island/Ship Shoal Inlet and Cobb Island (Northampton County), Wire Narrows Marsh along the Chincoteague Causeway (Accomack County), and in the urban colony around the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT) in Hampton.

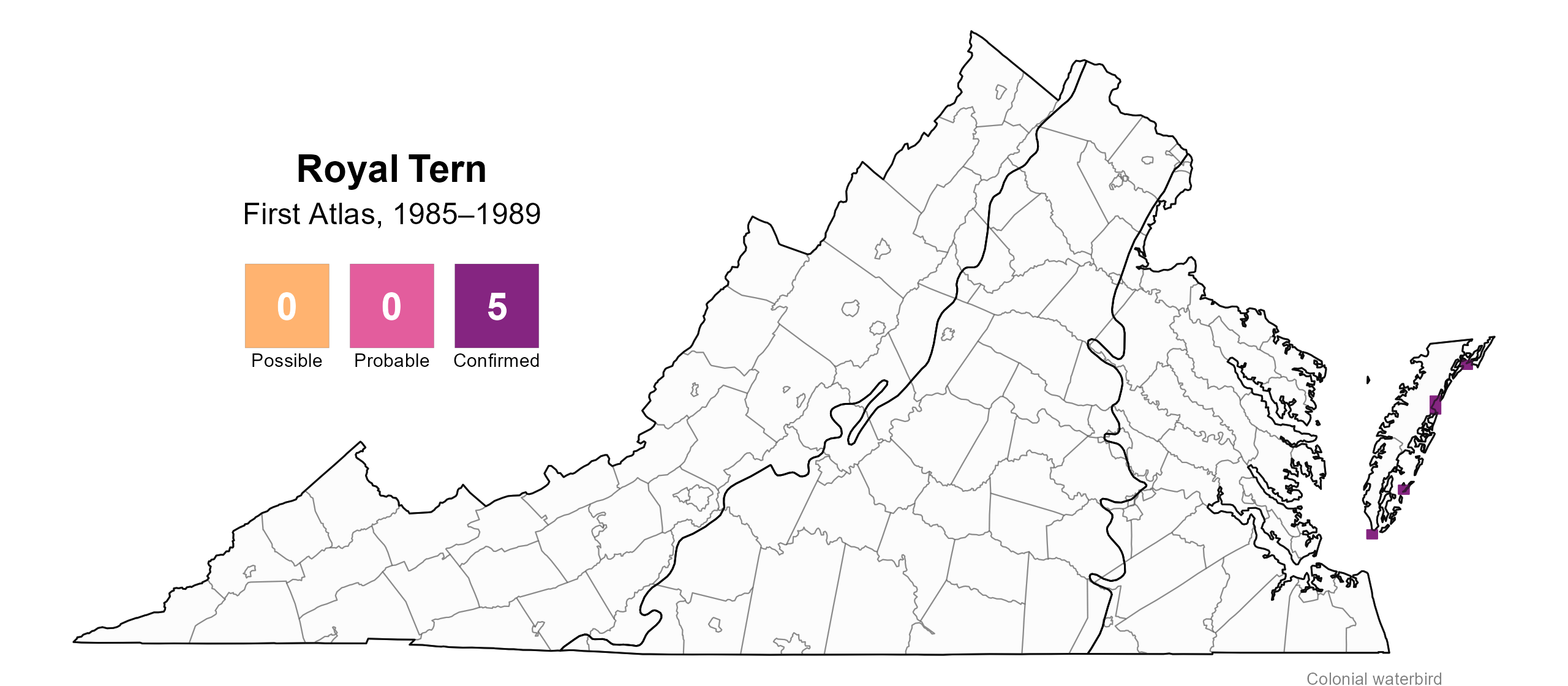

During the First Atlas, Royal Terns were confirmed at a few additional barrier island sites, but they were not yet present at the HRBT (Figure 2).

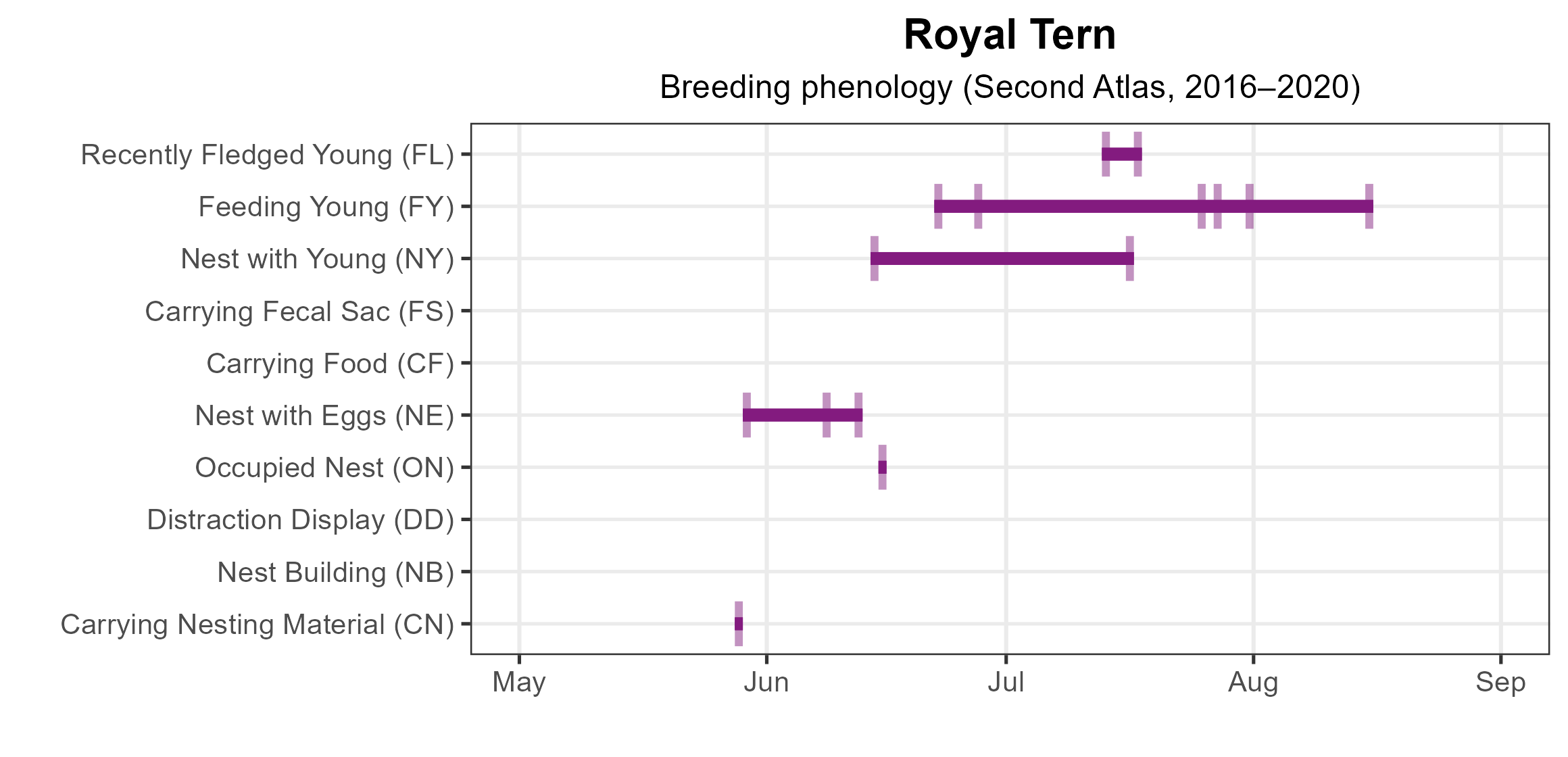

Royal Terns were on nests by May 29, and young were at the nest through July 16 (Figure 3). They were seen being fed by adults through August 15. Confirmations of recently fledged young, adults carrying food, and adults feeding young away from their few seaside colonies should be disregarded; young can be dependent on parents for months after they leave their breeding colonies (Buckley et al. 2021). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Royal Tern, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Royal Tern breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Royal Tern breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Royal Tern phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The Royal Tern had too few detections during the Atlas point count surveys to develop an abundance model. However, the distribution and size of Royal Tern colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

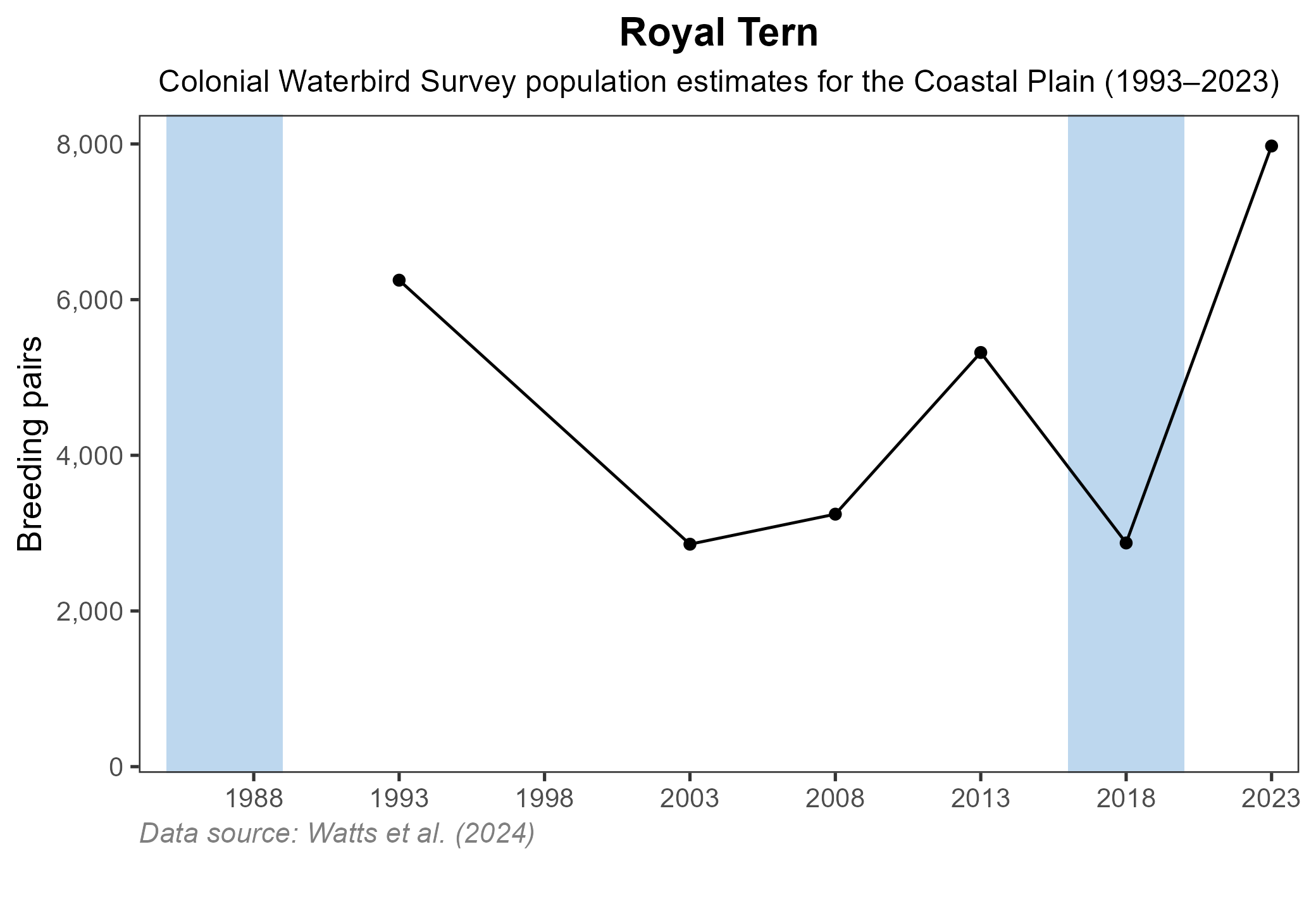

The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys recorded a moderate increase in the number of breeding pairs from 6,250 in 1993 to 7,974 in 2023, representing a 19% increase (Watts et al. 2024; Figure 4). Despite this increase, populations have fluctuated widely over the years. For example, in 2018, the number of breeding pairs was down to 2,874 (Watts et al. 2019). Strong interannual variation may reflect movement rather than population changes (Buckley et al. 2021).

Figure 4: Royal Tern population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

Despite modest population increases, Royal Tern populations are vulnerable to disturbance and loss of its limited number of nesting sites. Over 80% of Royal Tern and Sandwich Tern nesting in Virginia occurred on South Island near the HRBT, a colony that was displaced when the Virginia Department of Transportation began a project to expand the tunnel. VDWR and partners were able to provide alternative habitat on the historic Fort Wool (also known as Rip Raps Island) and floating barges, which now provide replacement habitat for multiple nesting seabird species, including Royal Tern (Sweeney et al. 2024).

Royal Tern juvenile survival has also been shown to be impacted by interactions between warming sea temperatures, fishery pressure, and fishery production, and these climate and anthropogenic threats will likely continue to be a threat to Virginia’s Royal Tern population persistence without management (Gibson et al. 2022). As with other beach-nesting species, Royal Terns can be protected by restricting disturbance and promoting public awareness around their nesting sites in addition to policy actions regarding climate and fishery threats.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Buckley, P. A., F. G. Buckley, and S. G. Mlodinow (2021). Royal Tern (Thalasseus maximus), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.royter1.01.1.

Gibson, D., Riecke, T. V., Catlin, D. H., Hunt, K. L., Weithman, C. E., Koons, D. N., Karpanty, S. M., & Fraser, J. D. (2023). Climate change and commercial fishing practices codetermine survival of a long-lived seabird. Global Change Biology 29:324–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16482.

Sweeney, C., K. Hunt, J. Fraser, and S. Karpanty (2024). Assessing avian response to the relocation of Virginia’s largest seabird colony, 2024 annual report. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L. Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L. Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.