Introduction

The Red-eyed Vireo is one of the most commonly heard birds in Virginia’s forests, delivering unending repetitions of its song, even in peak summer heat. One needs only to step outside near a patch of forest to hear one or two Red-eyed Vireos’ tireless efforts before they fade from attention into the background hum of noise. They can nest in deciduous or mixed woodlots as well as residential or urban areas with large trees (Cimprich et al. 2020), making them nearly ubiquitous during the breeding season. In the mountains of Virginia, the Red-eyed Vireo can coexist with the related Blue-headed Vireo (Vireo solitarius) in overlapping territories in the same forested habitat, a pattern that is not seen in the northeastern states and Canada, where the two species use distinct forest types (Hudman and Chandler 2002).

Breeding Distribution

The Red-eyed Vireo is found throughout the Commonwealth (Figure 1). The species is slightly less likely to occur in treeless areas of the Shenandoah Valley and Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area or on the fringes of the Eastern Shore. The likelihood of Red-eyed Vireos occurring in a block increases dramatically in areas with more forest cover.

Its distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled due to modeling limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on where the species occurred during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence Section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Red-eyed Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

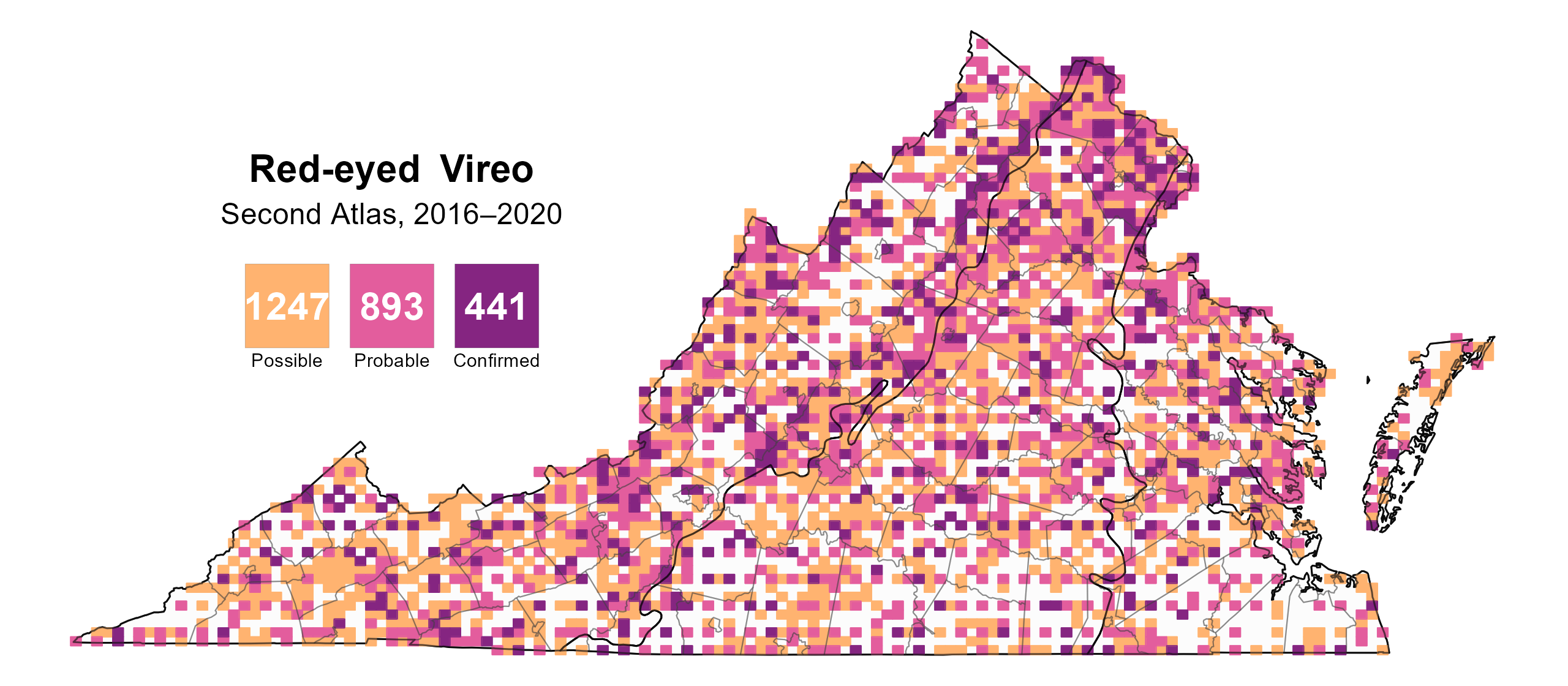

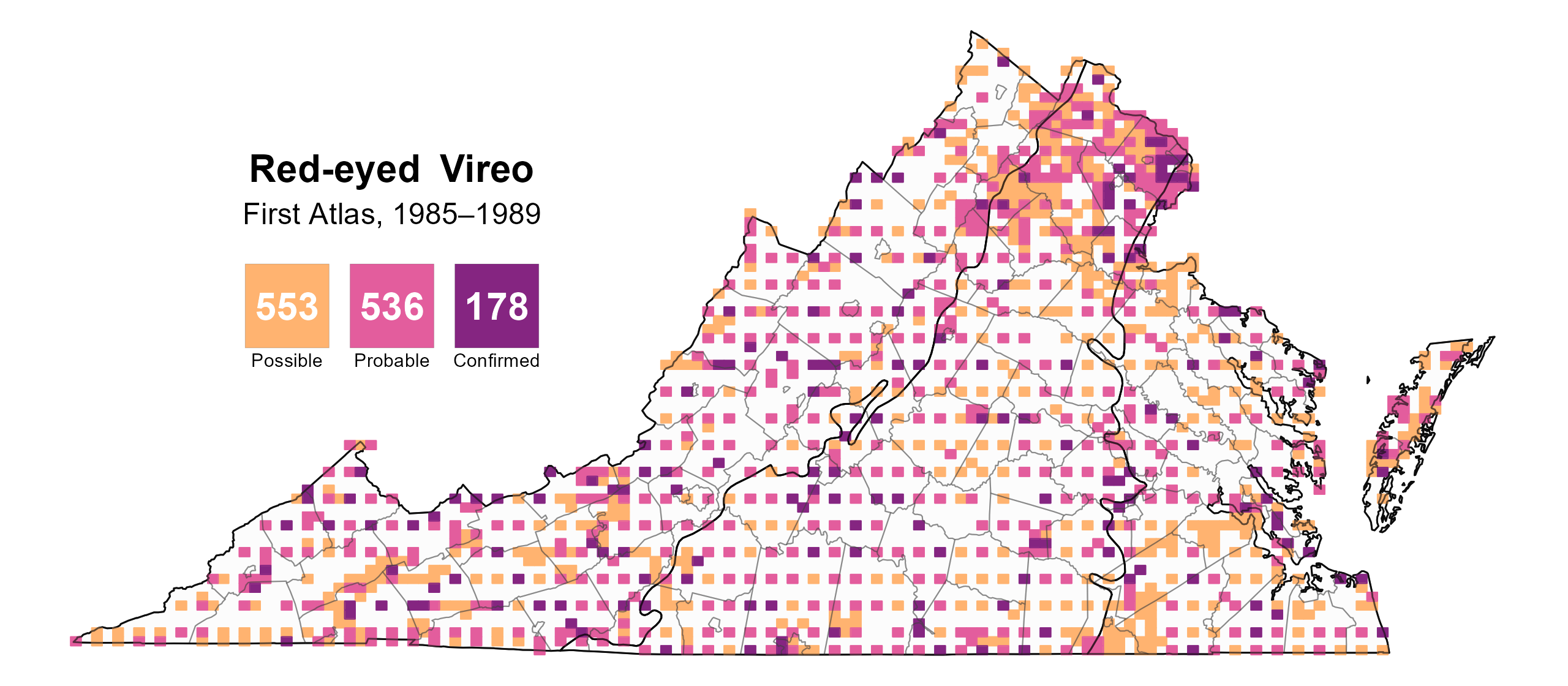

Red-eyed Vireos were confirmed breeders in 441 blocks and 93 counties and probable breeders in an additional 23 counties (Figure 2). Areas lacking breeding confirmations were mostly smaller independent cities such as Buena Vista, Salem, and Williamsburg, where the species was nonetheless still observed. Red-eyed Vireos were also confirmed breeders across the state during the First Atlas (Figure 3).

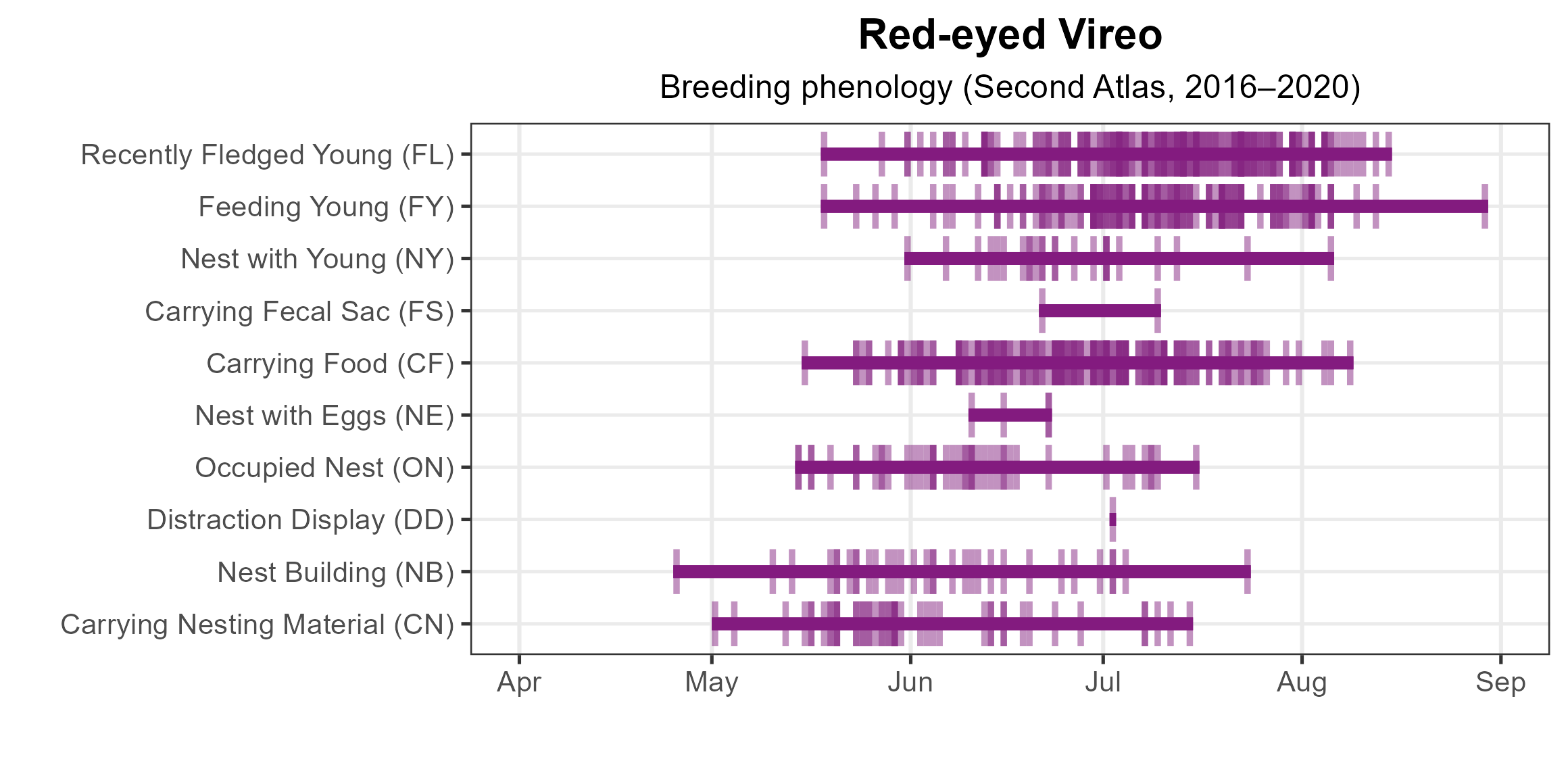

The earliest documentation of breeding was April 25 (nest building). The breeding season for Red-eyed Vireos extends late for a neotropical migrant. Dependent fledglings were observed through August 14 and feed young through August 29 (Figure 4). Observers documented Red-eyed Vireos performing every type of breeding activity, although most confirmations came from observations of recently fledged young, adults carrying food, and adults feeding young. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Red-eyed Vireo, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Red-eyed Vireo breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Red-eyed Vireo breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Red-eyed Vireo phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

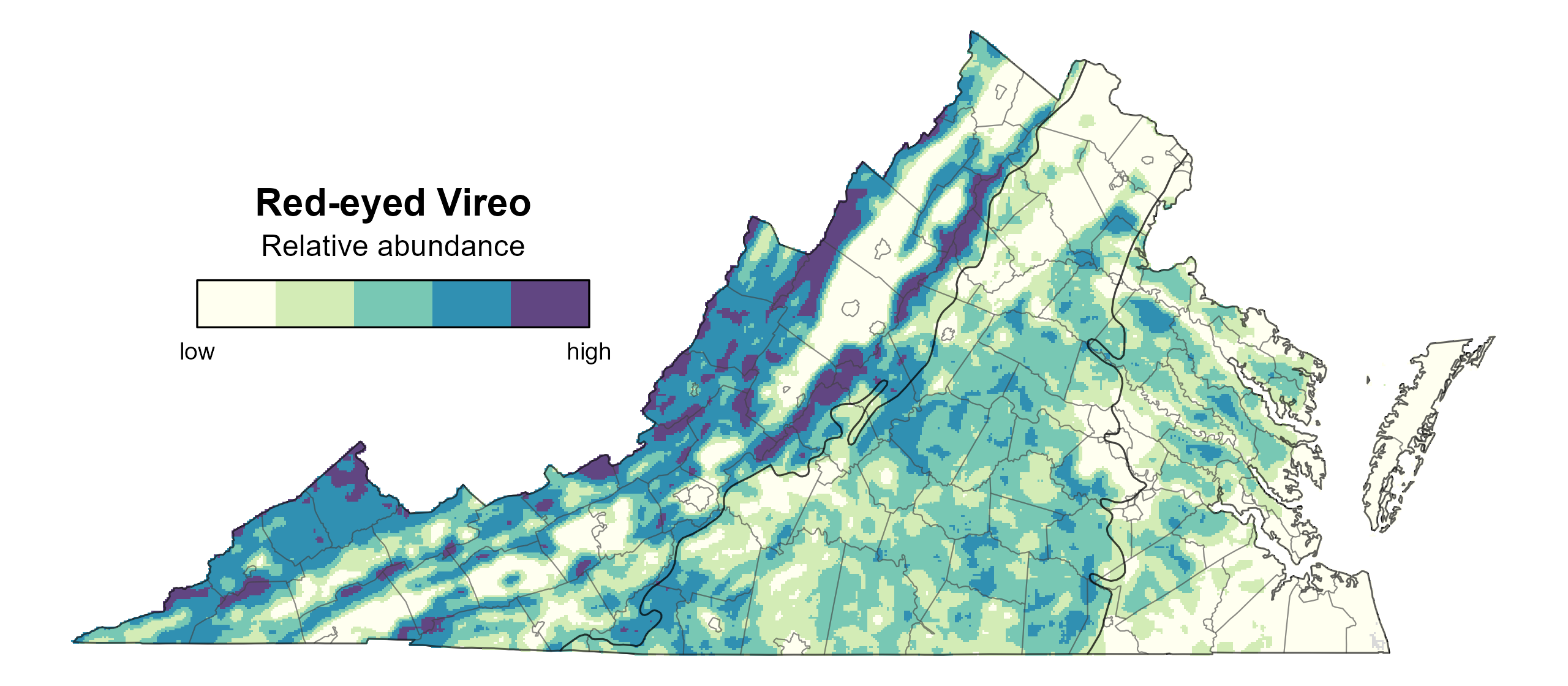

Although the Red-eyed Vireo is present statewide in the appropriate habitat, its relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the western portion of the Mountains and Valleys region and along the Blue Ridge Mountains and moderate in the central and southern Piedmont region and in areas of the Coastal Plain mostly north of the James River (Figure 5). Its abundance was predicted to be lower in the Shenandoah Valley, the northern Piedmont, the greater Richmond area, the Tidewater area, as well as the outer Western Shore and the entirety of the Eastern Shore.

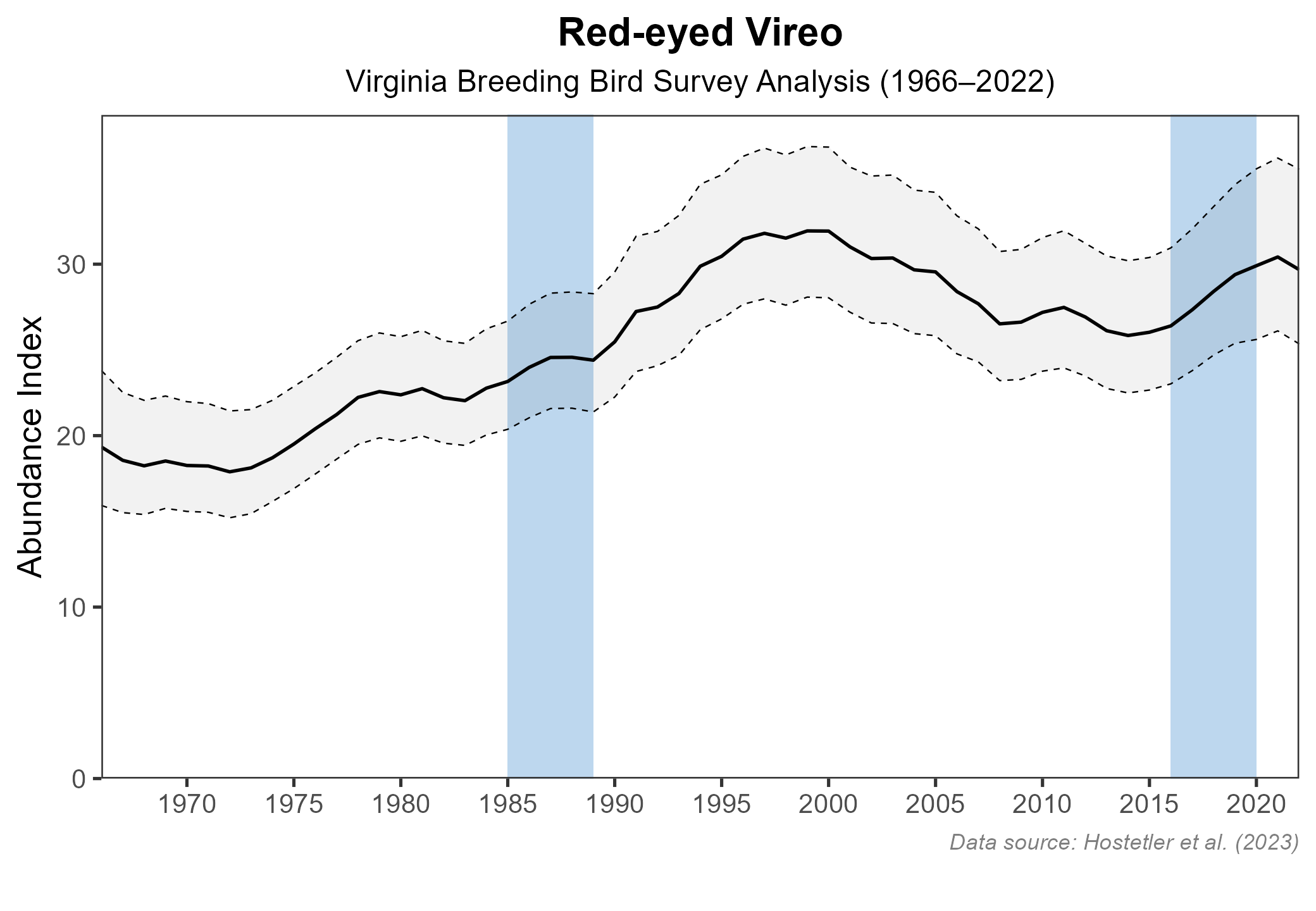

The total estimated population of Red-eyed Vireos in the state is 1,863,000 detectable individuals (with a range between 1,751,000 and 1,984,000). This makes the species the sixth most abundant breeder in the state (among those species for which abundance could be modeled) and the most abundant neotropical migrant. Red-eyed Vireo populations are increasing in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) reported a significant increase of 0.77% in its population per year from 1966–2022 in the state and a similar significant increase of 0.47% per year from 1966–2022 between the Atlases (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6).

Figure 5: Red-eyed Vireo relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Red-eyed Vireo population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Common, widespread, and abundant across Virginia and beyond, and with a population that continues to slowly grow, the Red-eyed Vireo is a species that is expected to continue thriving into the future. Although breeding has been reported in forest fragments as small as 1.2 acres (0.5 hectares) in its Mid-Atlantic range (Cimprich et al. 2020), it may do less well in fragments that are isolated (Cimprich et al. 2020), in that it may be susceptible to conversion of forests to other land uses. As a family, vireos have done well over the past 60 years, with populations continuing to increase in contrast to other songbirds, such as warblers, whose populations are declining as a group (Rosenberg et al. 2019).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Cimprich, D. A., F. R. Moore, and M. P. Guilfoyle (2020). Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald). Cornell Lab of Ornithology Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.reevir1.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Hudman, S. P., and C. R. Chandler (2002). Spatial and habitat relationships of Red-Eyed and Blue-Headed Vireos in the Southern Appalachians. The Wilson Bulletin 114:227–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4164445.

Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, et al. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366:120–24.