Introduction

The Northern Flicker’s piercing kleew call is often heard far before it is seen. This species is a ground-foraging bird equally at home on decaying logs as it is on anthills in an urban park or lawn. Flickers nest in forest edges, woodlots, and in Virginia, young clear-cuts with retained standing dead trees, where they have access to open ground for foraging (Conner et al. 1975). They are also associated with open pine savannas such as those found in Piney Grove Preserve, where on one occasion they were documented nesting in an enlarged cavity excavated by Red-cockaded Woodpeckers (Dryobates borealis) (Wilson et al. 2014). They require dead or diseased trees or snags or trees softened by fungal pathogens for cavity excavation (Conner et al. 1975). They excavate in softer wood than other woodpeckers (Lorenz et al. 2015).

The subspecies present in Virginia is the Yellow-shafted Flicker (Colaptes auratus auratus), which was lumped with the western subspecies Red-shafted Flicker (C. a. cafer) in 1982 (Eisenmann et al. 1982). There are some autumn records of intergrades in Virginia but only one pure Red-shafted Flicker (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). In addition to the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius), this is our most migratory woodpecker. Despite their familiarity, Northern Flickers are experiencing population declines, and much remains unknown about their ecology and behavior.

Breeding Distribution

Due to model limitations, the occurrence of Northern Flickers could not be modeled (see Interpreting Species Account). For information on where Northern Flickers occur in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

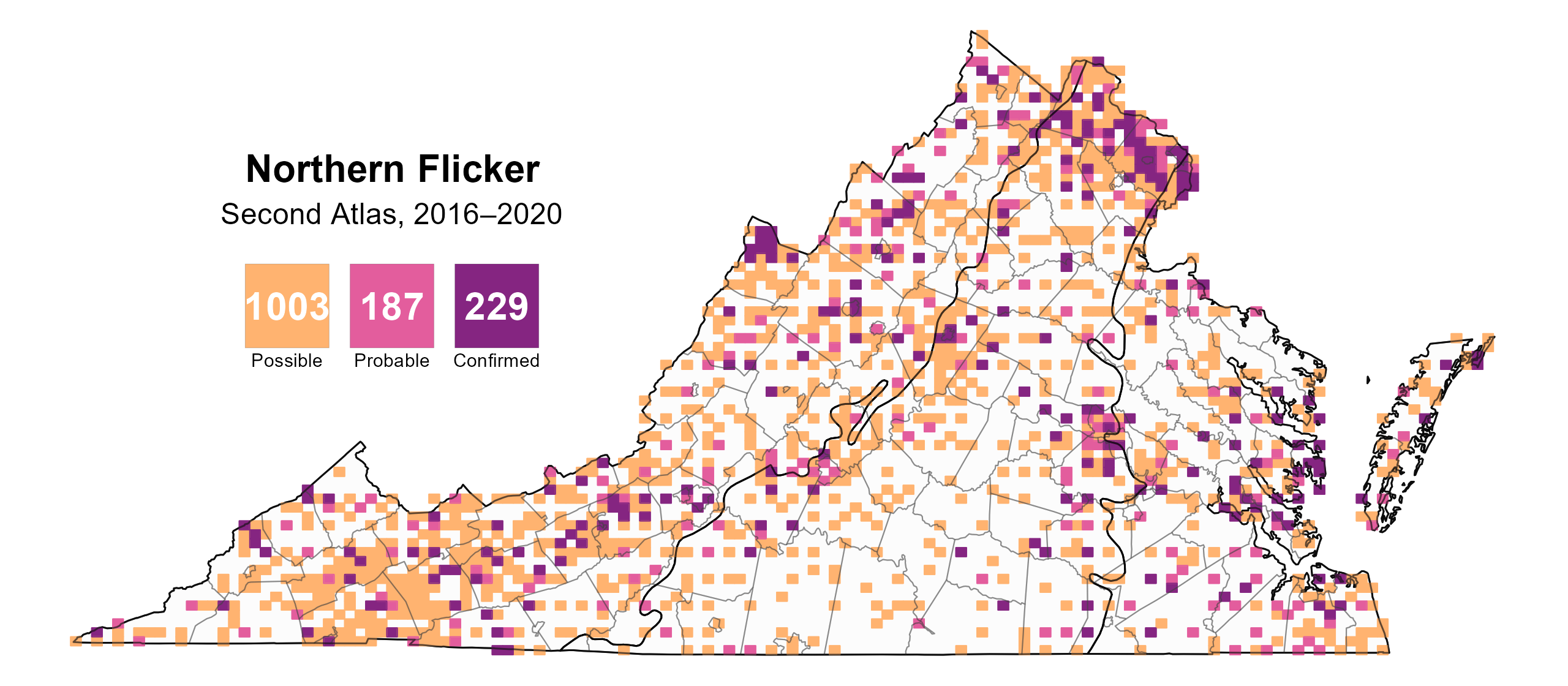

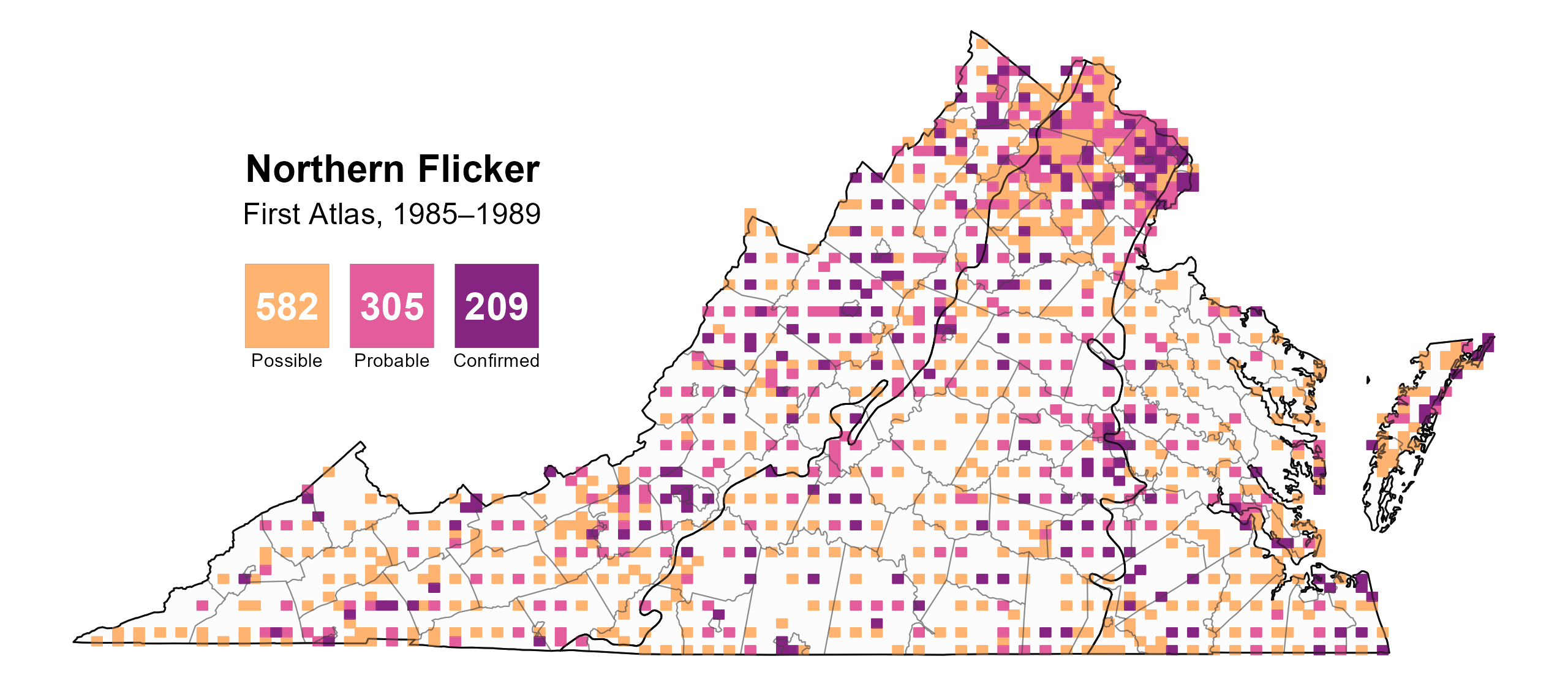

Northern Flickers were confirmed breeders in 229 blocks and 88 counties and probable breeders in an additional 19 counties (Figure 1). Like Pileated Woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus), they were difficult to track to their nests for confirmation and thus were considered only possible breeders in many additional blocks. Despite a declining population trend (see Population Status), its breeding evidence distribution during the Second Atlas was largely similar to that during the First Atlas (Figure 2), suggesting stability in overall distribution between Atlases.

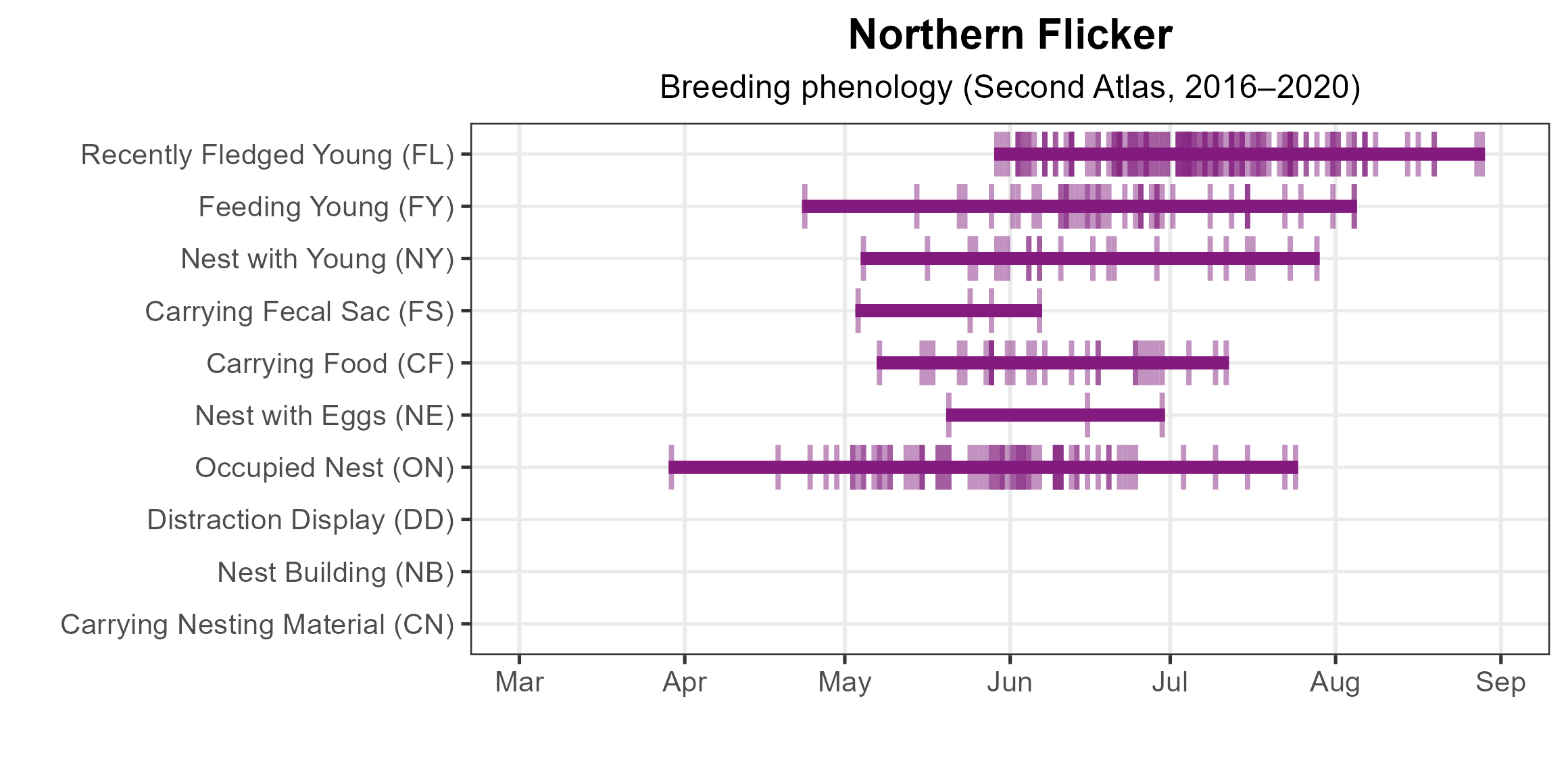

Flickers were observed occupying nests from March 29 onward, including reports from Atlas volunteers of nests in woodpecker and American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) nest boxes, utility poles, and a dead pine tree (Figure 3). First evidence of young was documented on April 23. Breeding continued through August, with recent fledglings seen as late as August 28. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Northern Flicker, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Northern Flicker breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Northern Flicker breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Northern Flicker phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

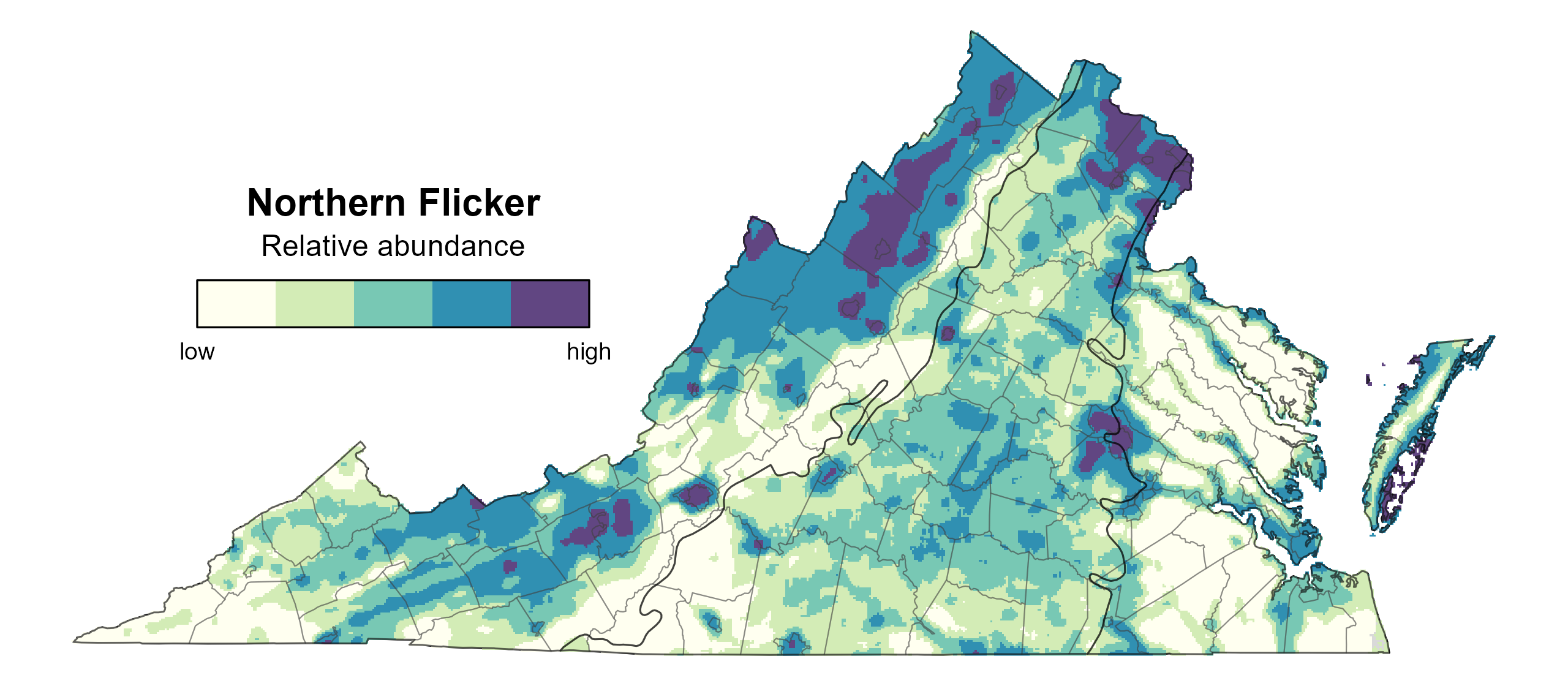

Northern Flicker relative abundance was estimated to be highest in broad areas of the Mountains and Valley region, including the Shenandoah Valley, Alleghany Mountains, and a broad swath of southwestern Virginia, as well as in the northern and southern-central Piedmont and the river corridors of the Coastal Plain, the Eastern Shore, and the Newport News/northern Tidewater area (Figure 4).

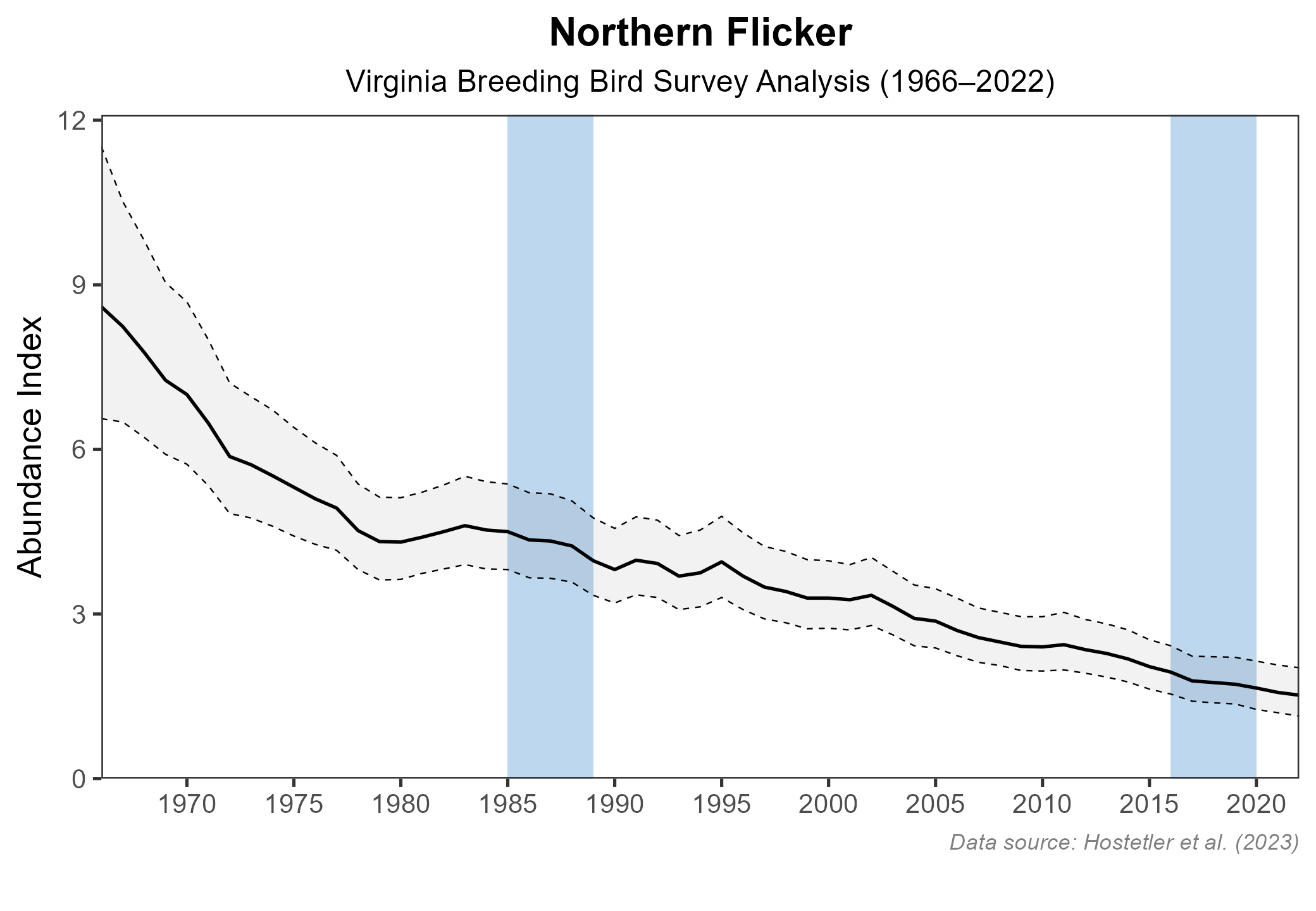

The estimated Northern Flicker population in the state is approximately 202,000 individuals (with a range between 112,000 and 368,000). Although they are a relatively abundant species, Northern Flicker populations are declining in Virginia. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed a significant decline of 3.03% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between Atlases, its population decreased by a significant 2.87% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 4: Northern Flicker relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 5: Northern Flicker population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The Northern Flicker is declining in the eastern portion of its range, including the Commonwealth. Given this decline, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan includes this species as a Tier III Species of Greatest Conservation Need (High Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025). The reasons for its decline are unclear. The species is flexible in its selection of nesting habitat, much of it altered by humans and in seemingly ample supply as it includes suburban areas, parks, open fields with scattered trees, forest edges, and even clearcuts. It is hypothesized that a declining availability of microhabitat in the form of dead or dying nest trees may be in play. Removal of dead and diseased trees or parts of trees from urban/suburban areas (Wiebe and Moore 2023) or from areas where they may pose a danger to humans could be factors contributing to population losses. Increased pesticide use at Northern Flicker foraging sites, including in golf courses, agricultural fields, and yards, could also play a role (Wiebe and Moore 2023). Competition with European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) for nest cavities has also been suggested as a potential cause (Wiebe and Moore 2023). Investigating and identifying factors limiting Flicker populations is an important first step toward effective conservation for the species.

Suggested conservation actions for Northern Flickers are otherwise similar to those for other woodpecker species. For example, this species benefits from landowners and land managers leaving large trees for nesting and stumps and fallen logs for foraging. Flickers are 20 times more likely than the average species to collide with residential buildings that are one to three stories tall (Loss et al. 2014). While it is unclear whether this is having population-level impacts, measures taken to reduce collisions, such as the installation or retrofitting of bird friendly glass, can be of benefit.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Conner, R. N., R. G. Hooper, H. S. Crawford, and H. S. Mosby (1975). Woodpecker nesting habitat in cut and uncut woodlands in Virginia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 39:144–150. https://doi.org/10.2307/3800477.

Eisenmann, E., B. L. Monroe Jr., K. C. Parkes, L. L. Short, R. C. Banks, T. R. Howell, N. K. Johnson, and R. W. Storer (1982). Thirty-fourth supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union’s check-list of North American birds. The Auk 99:1CC–16CC.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Lorenz, T. J., K. T. Vierling, T. R. Johnson, and P. C. Fischer (2015). The role of wood hardness in limiting nest site selection in avian cavity excavators. Ecological Applications 25:1016–1033. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-1042.1.

Loss, S. R., T. Will, S. S. Loss, and P. P. Marra (2014). Bird–building collisions in the United States: estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. Condor 116:8–23.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, Virginia, USA. 506 pp.

Wiebe, K. L., and W. S. Moore (2023). Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.norfli.02.

Wilson, M. D., B. D. Watts, C. Lotts, F. M. Smith, and B. J. Paxton (2014). Investigation of Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in Virginia: year 2013 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-14-002. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 17 pp.