Introduction

The Hairy Woodpecker is an uncommon, permanent resident in Virginia. Their strident, harsh peek calls signal a shakeup at the birdfeeder, where they are highly dominant to other species (Miller et al. 2017). They use a variety of wooded habitats, nesting over a wide range of basal areas, canopy heights, stem densities, and distances to clearings (Conner and Adkisson 1977). This species’ scientific epithet “villosus” and common name “hairy” refer to the shaggy, hairlike texture of their white back feathers, a contrast to the soft, downlike feathers in the same place on the Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) (Jackson and Ouellet 2020). Hairy Woodpeckers and Downy Woodpeckers share very similar plumage despite the two species not being closely related. This convergence may allow Downy Woodpeckers to take advantage of the larger size and aggressive nature of Hairy Woodpeckers in a form of interspecific social dominance mimicry (Prum and Samuelson 2012).

Breeding Distribution

Hairy Woodpeckers occur in all regions of the state, but they are more likely to occur in the western areas of the Mountains and Valleys region than in the Coastal Plain (Figure 1). The likelihood of this species occurring in a block increases as the proportion of forest cover increases and is positively associated with forest edge habitat, forest patch size, and agricultural lands. It is less likely to occur in blocks with a greater number of habitat types.

Hairy Woodpecker distribution during the First Atlas and the ensuing change between Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Hairy Woodpecker breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

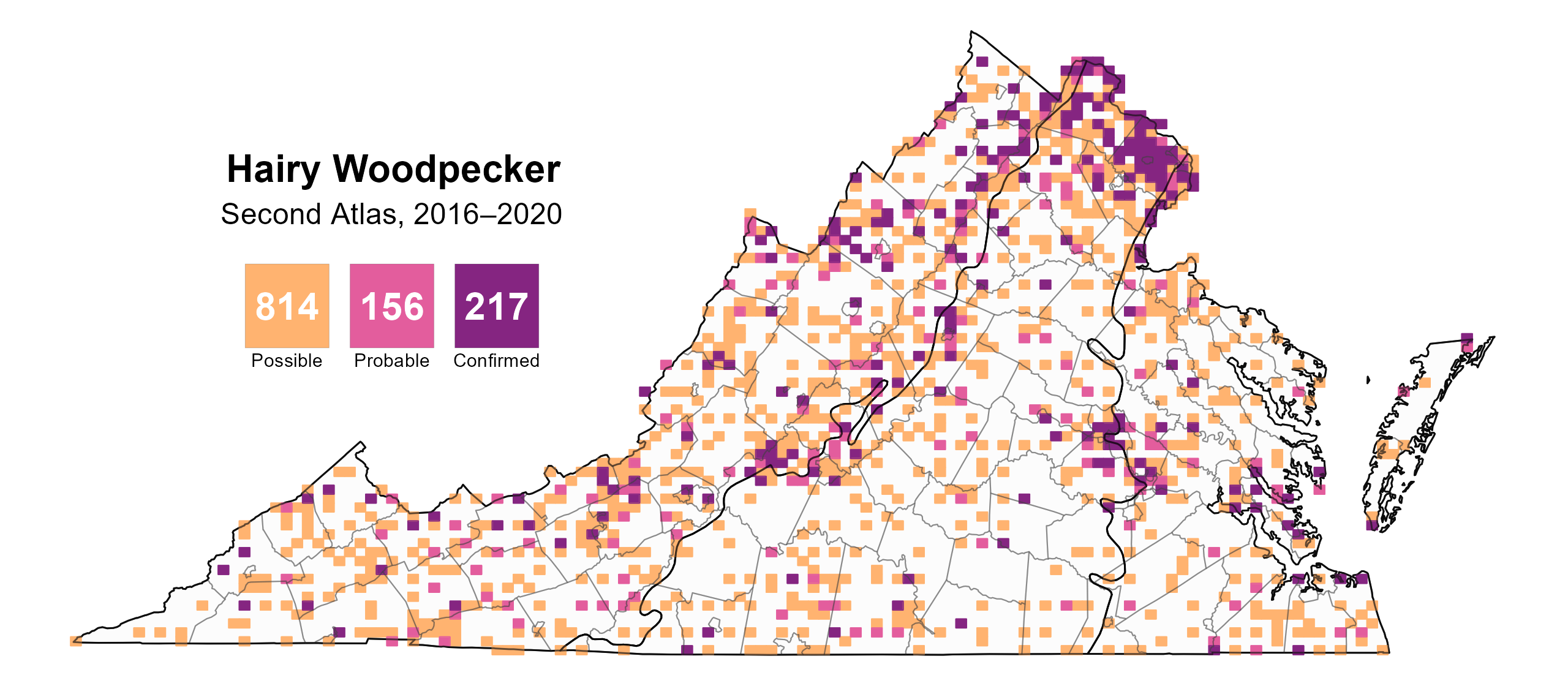

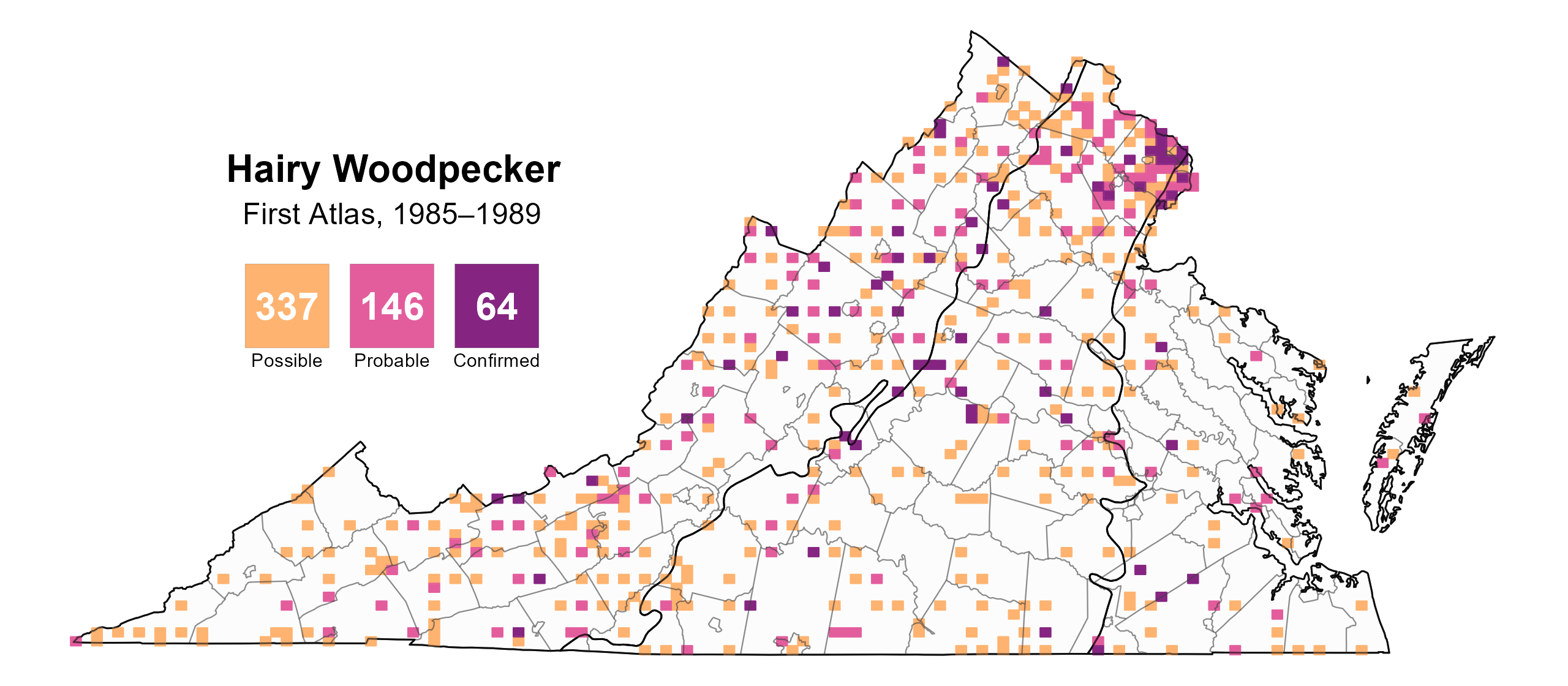

Hairy Woodpeckers were confirmed breeders in 217 blocks and 73 counties and were probable breeders 25 additional counties (Figure 2). Volunteers observed Hairy Woodpeckers breeding in all regions of the state in the First Atlas as well, although there were fewer overall breeding observations (Figure 3). This result is likely indicative of their increase between Atlases (see Population Status section), but it also may partially reflect the increased survey effort during the Second Atlas.

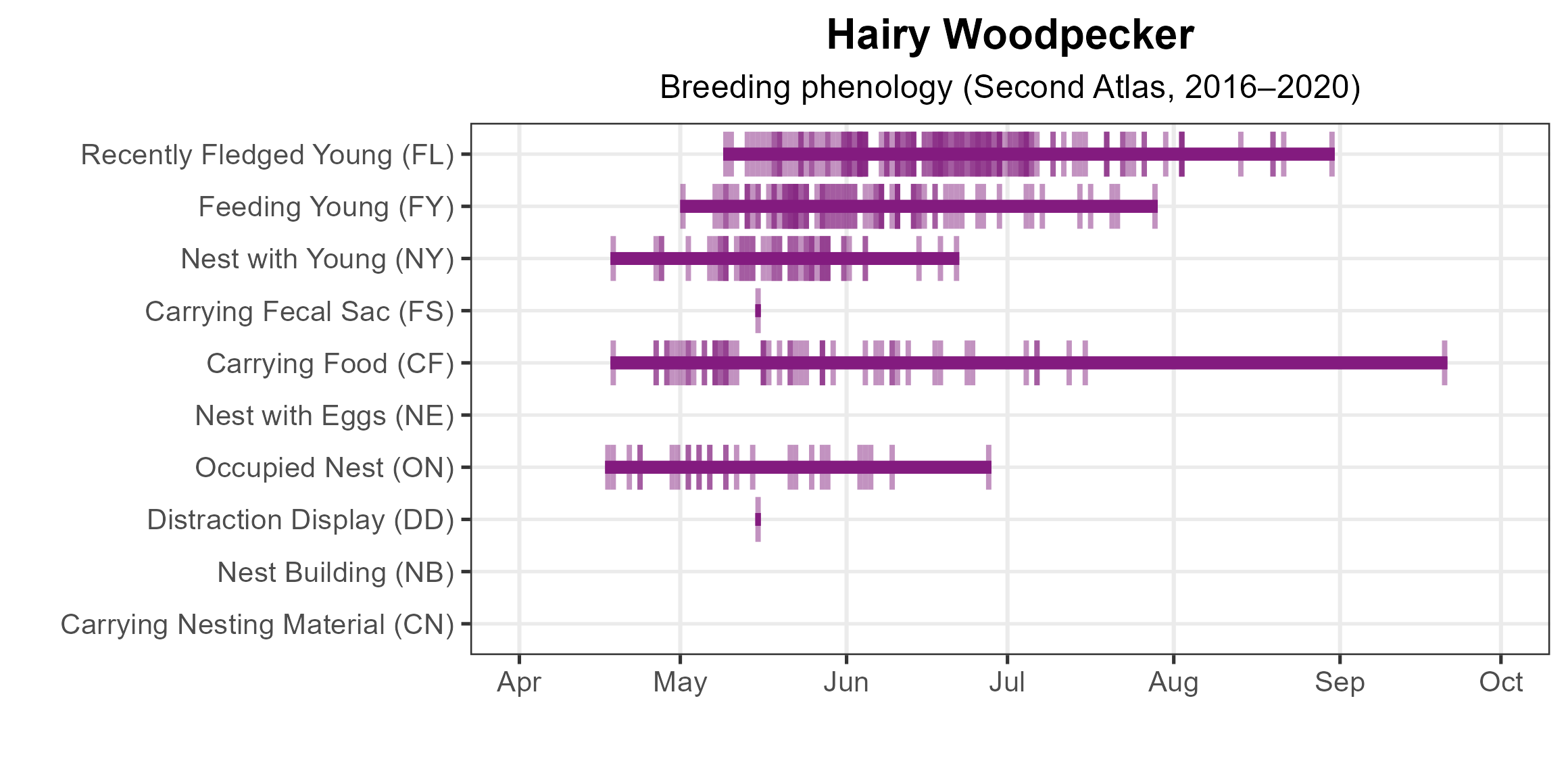

Hairy Woodpeckers were observed nesting by April 17, and breeding continued to be observed through August, with the last fledglings seen on August 30 (Figure 4). Most observations were of fledglings. Hairy Woodpeckers can become remarkably shy during the breeding season. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Hairy Woodpecker, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Hairy Woodpecker breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Hairy Woodpecker breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Hairy Woodpecker phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Hairy Woodpecker relative abundance was estimated to be highest in forested, high-elevation mountains, particularly around Bath and Highland Counties. Abundance was lower in surrounding areas where the amount of agricultural habitat likely increases (Figure 5).

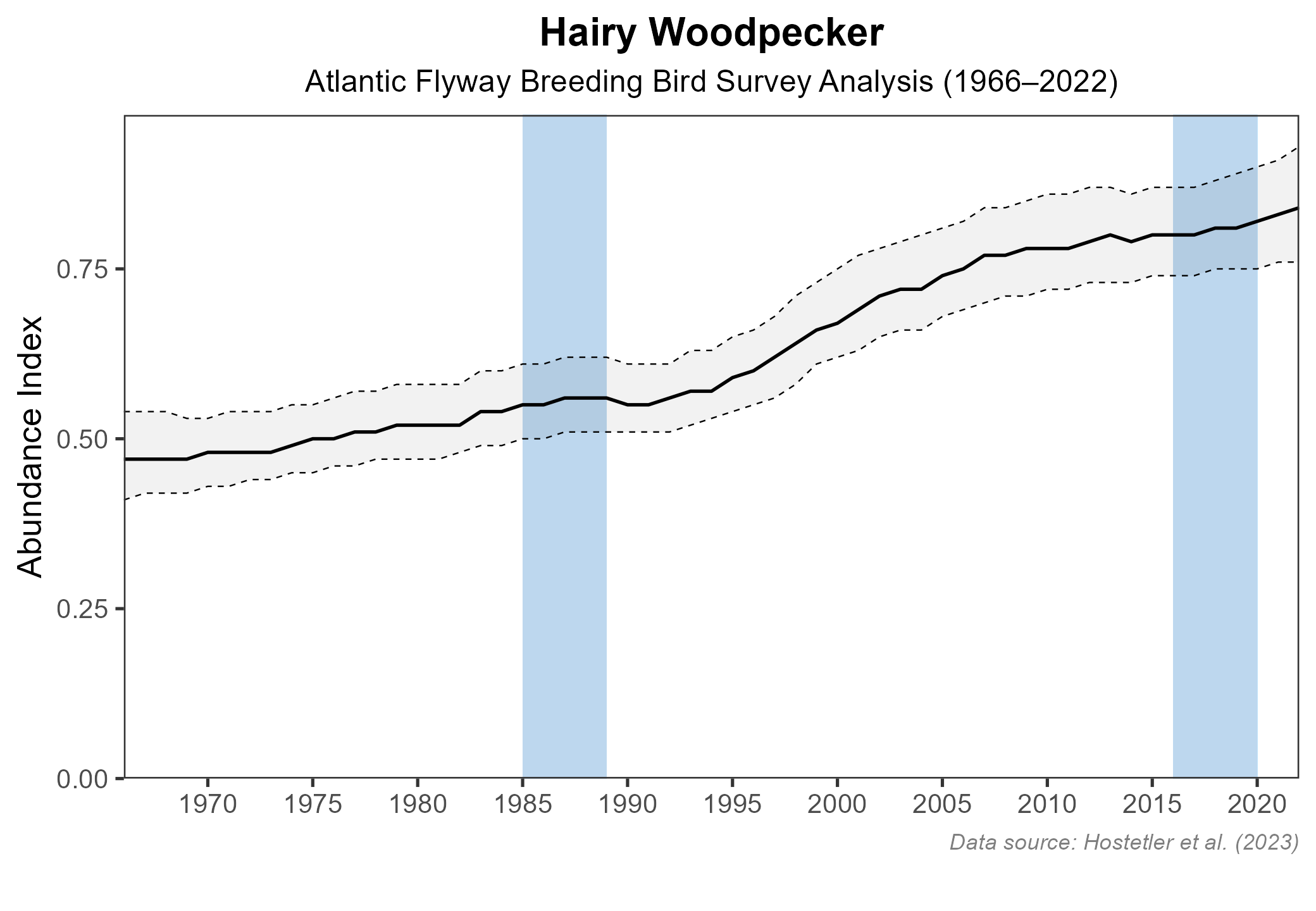

The total estimated Hairy Woodpecker population in the state is approximately 213,000 individuals (with a range between 82,000 and 550,000). North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data show that population trends for Hairy Woodpecker are positive in the Atlantic Flyway region (BBS data at the Virginia-scale do not produce credible trends) with a significant increase of 1.03% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6). Between Atlases, Atlantic Flyway BBS trend data showed a similar significant increase of 1.21% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Hairy Woodpecker relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Hairy Woodpecker population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Hairy Woodpeckers populations are secure in the Commonwealth, and they are not a species of concern. Because they are typically found in forest interiors, leaving stands larger than approximately 10 acres (4 hectares) can help maintain their populations (Jackson et al. 2020).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Conner, R. N., and C. S. Adkisson (1977). Principal component analysis of woodpecker nesting habitat. The Wilson Bulletin 89:122–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4160877.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Jackson, J. A., and H. R. Ouellet (2020). Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.dowwoo.01.

Jackson, J. A., H. R. Ouellet, and B. J. Jackson (2020). Hairy Woodpecker (Dryobates villosus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.haiwoo.01.

Miller, E. T., D. N. Bonter, C. Eldermire, B. G. Freeman, E. I. Greig, L. J. Harmon, C. L., and W. M. Hochachka (2017). Fighting over food unites the birds of North America in a continental dominance hierarchy. Behavioral Ecology 28:1454–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arx108.

Prum, R. O., and L. Samuelson (2012). The hairy–downy game: a model of interspecific social dominance mimicry. Journal of Theoretical Biology 313:42–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.07.019.