Introduction

Cliff Swallows are relatively uncommon in the state and were first documented as breeding in Virginia in 1969 (Grant and Quay 1977; Brown and Brown 2020). In the Commonwealth, they breed in colonies and build their nests exclusively on artificial structures, such as bridges and buildings, while in other areas, they may also build them on cliff faces, under large tree limbs, or at the entrance of caves (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; Brown et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Limitations imposed by the data and model prevented the development of occupancy models for the Cliff Swallow (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on their breeding distribution, see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

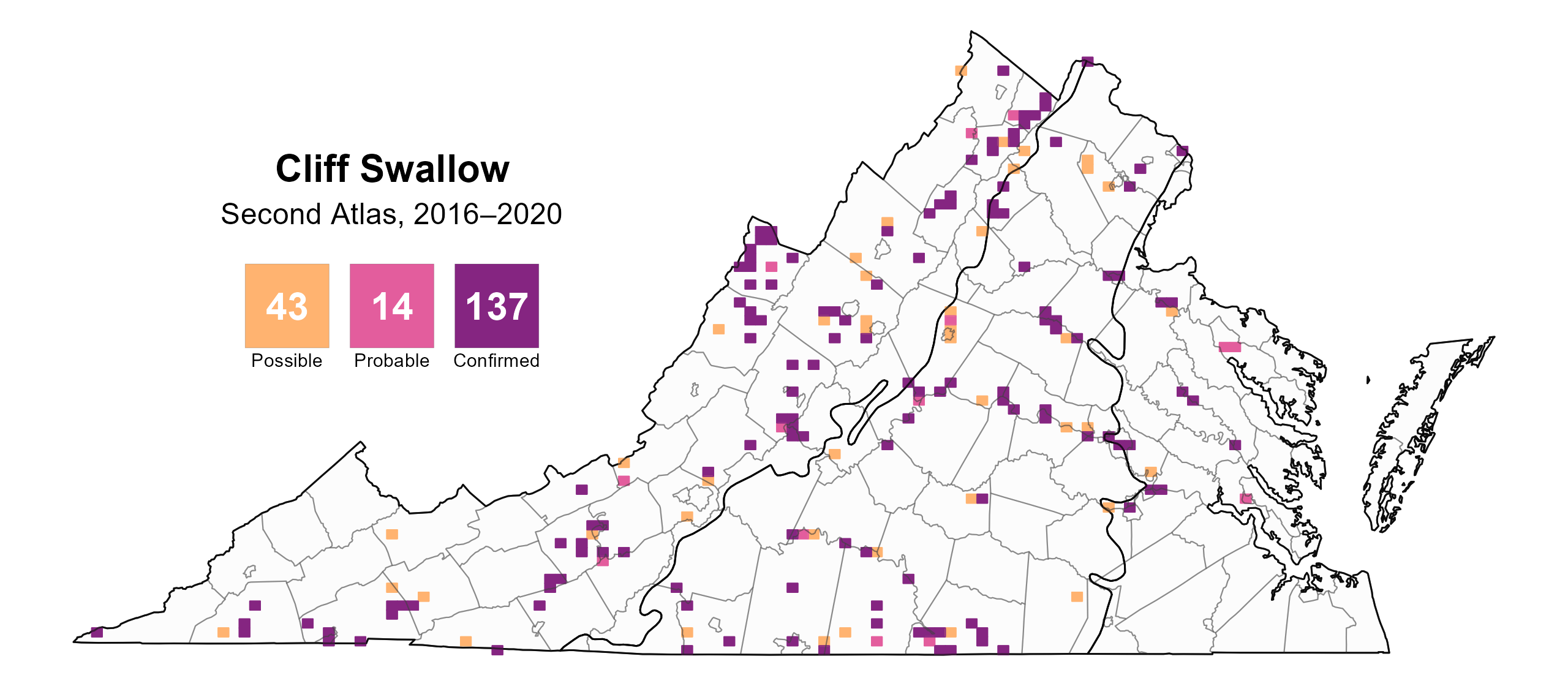

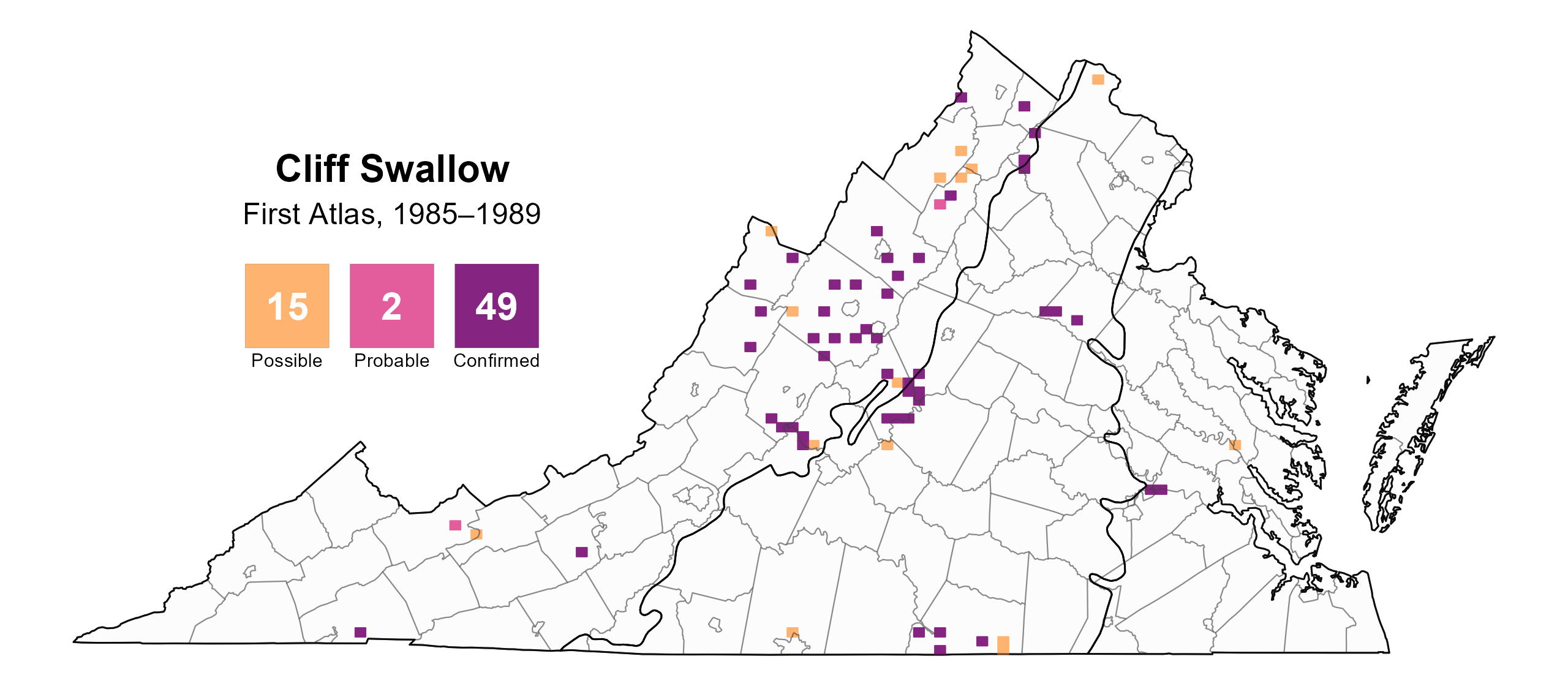

Cliff Swallows were confirmed breeders in 137 blocks and 61 counties and found to be probable breeders in three additional counties (Albemarle, Craig, and Richmond) and the city of Williamsburg (Figure 1). As expected, given the Cliff Swallow’s more westerly distribution within the state, the bulk of breeding confirmations were in the Mountains and Valleys and Piedmont regions. In some cases, colonies were discovered dotting the courses of major rivers systems, such as the Shenandoah, James, and Roanoke. During the First Atlas, fewer breeding confirmations were recorded; however, this difference may also have been due to less volunteer effort (Figure 2).

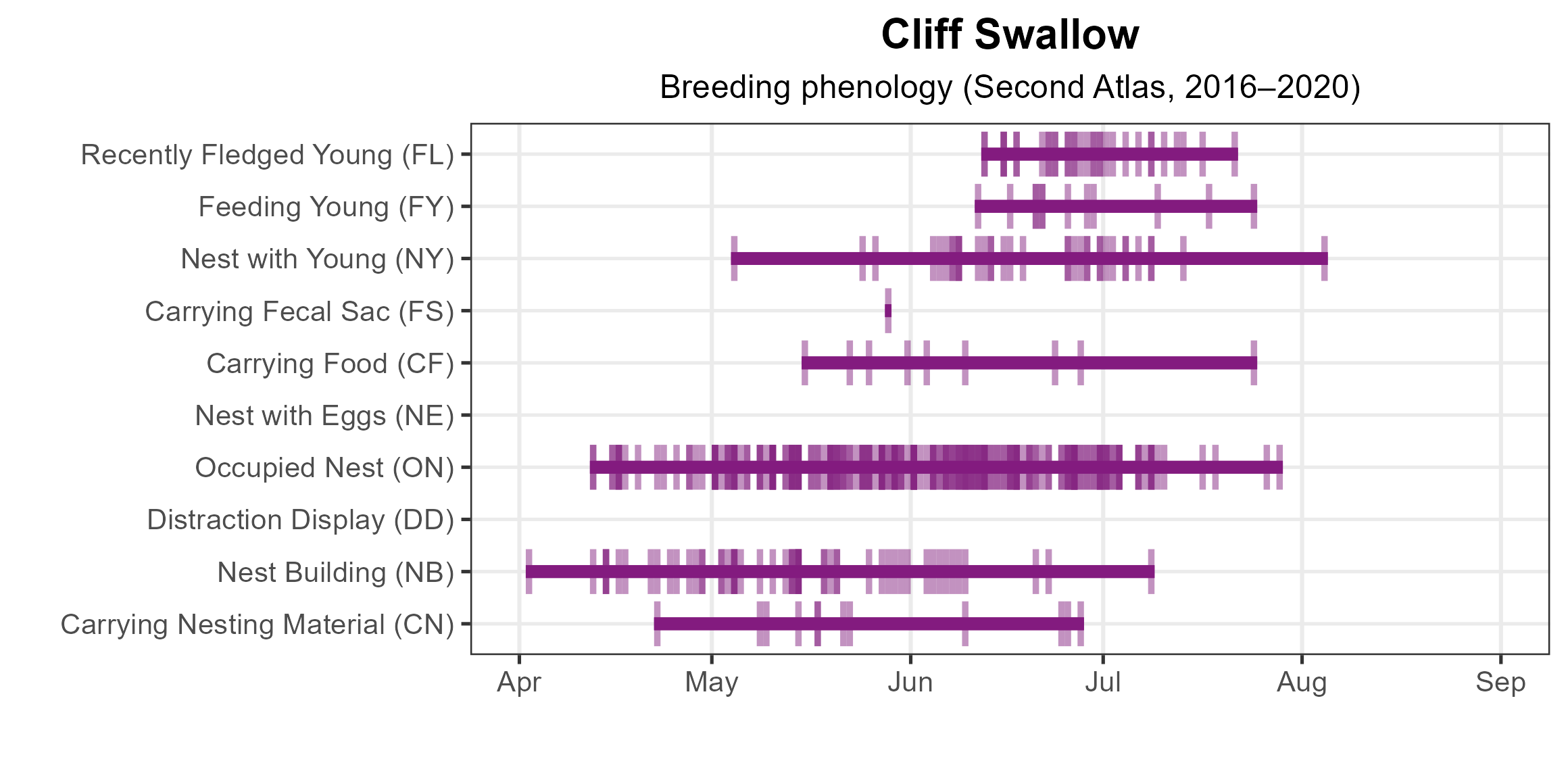

Nest building was the earliest breeding behavior recorded (April 2) (Figure 3). The most frequent breeding observation was occupied nests (April 12 – July 28), and nests with young were documented until August 4. For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Cliff Swallow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Cliff Swallow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Cliff Swallow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

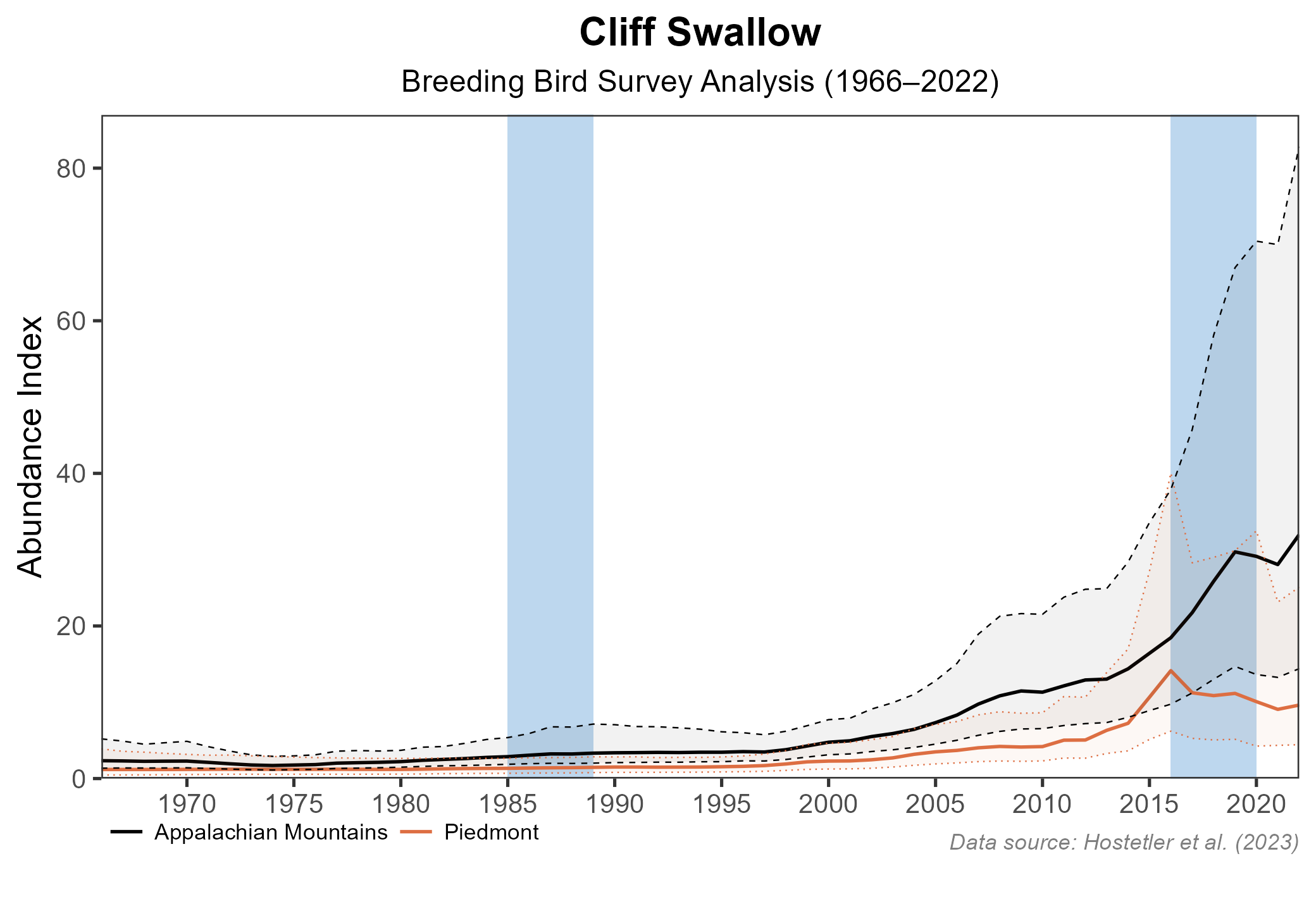

Limited detections during the point count surveys prevented the development of an abundance model for the Cliff Swallow. Additionally, the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data do not produce a credible population trend for Virginia. However, based on the Piedmont and Appalachian Region BBS population trend data, the Cliff Swallow population trend increased annually by a significant 3.78% and 4.76% in those regions, respectively, between 1961 and 2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 4). Between Atlases (from 1987 to 2018), the Piedmont region BBS data showed that its population trend experienced a significant increase of 6.78% per year, and the Appalachian BBS data showed it experienced a similar significant 6.89% increase per year.

Figure 4: Cliff Swallow population trend for the Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Cliff Swallows are relatively uncommon in the state, but their populations are increasing within the Coastal Plain region and in the other two-thirds of the state. Thus, they are not considered to be a species of conservation concern in Virginia, and no dedicated conservation projects underway.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Brown, C. R., M. B. Brown, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.cliswa.01.

Grant, G. S., and Quay, T. L. (1977). Breeding biology of Cliff Swallows in Virginia. The Wilson Bulletin 89:286–290.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Watts, B. (2017). Cliff Swallow population explosion continues in coastal Virginia. Center for Conservation Biology, Williamsburg, VA, USA. https://ccbbirds.org/2017/07/05/cliff-swallow-population-explosion-continues-in-coastal-virginia.