Introduction

The Caspian Tern is king among terns as the largest species in the world. In Virginia, it is a common migrant in the Coastal Plain but rare in winter and breeding seasons (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). This species’ breeding history in the Commonwealth is patchy. Pre-1900, it was apparently more common than now, but like many other terns, it was hunted for the millinery trade (Bailey 1913). It was absent as a breeder until a single nest was discovered in 1974 (Weske et al. 1977). Although the species is primarily a breeder in the interior of the continent, the Caspian Tern has expanded to a number of new sites in the coastal southeastern United States. All of these southeastern breeders have used new sites created from dredged material, with Virginia as a notable exception where the species is only known to inhabit natural estuarine islands and marshes (McNair 2000).

Breeding Distribution

The Caspian Tern was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Caspian Tern only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

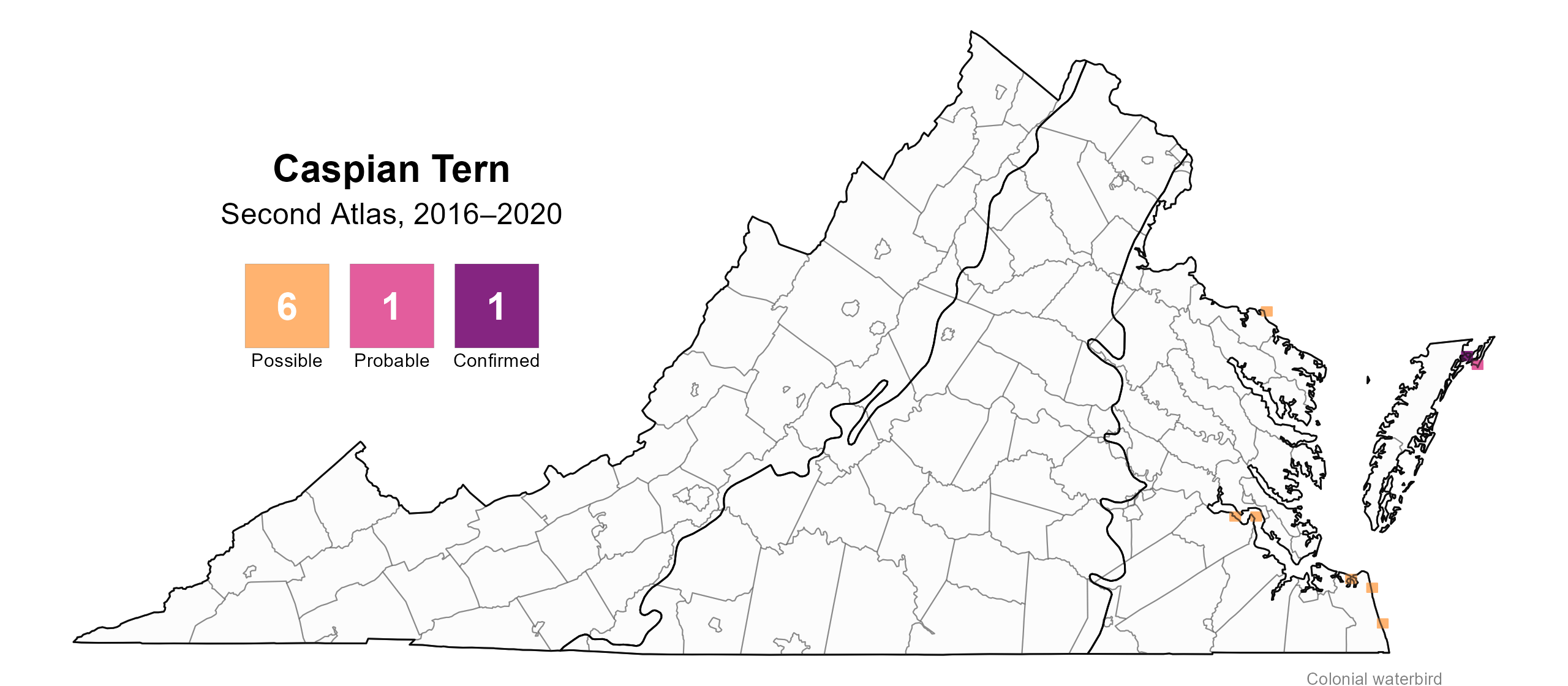

Given the breeding biology of the species, Caspian Terns are unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Confirmation of breeding was based on records generated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

Caspian Terns breed exclusively in the Coastal Plain region of Virginia. Breeding was confirmed in just one block in Accomack County, near Chincoteague (Figure 1).

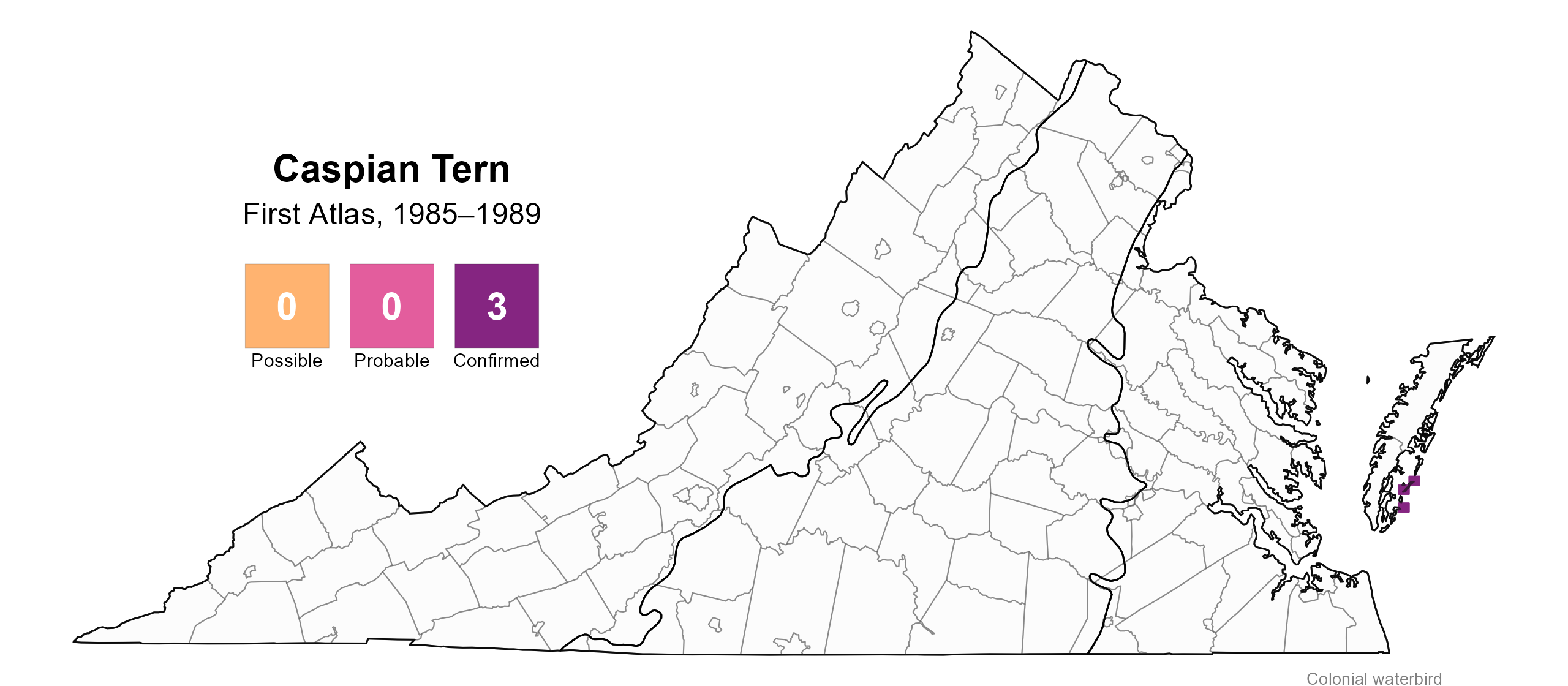

During the First Atlas, breeding was confirmed in three blocks on barrier islands in Northampton County (Figure 2), but no Caspian Terns were found breeding in these locations during the Second Atlas.

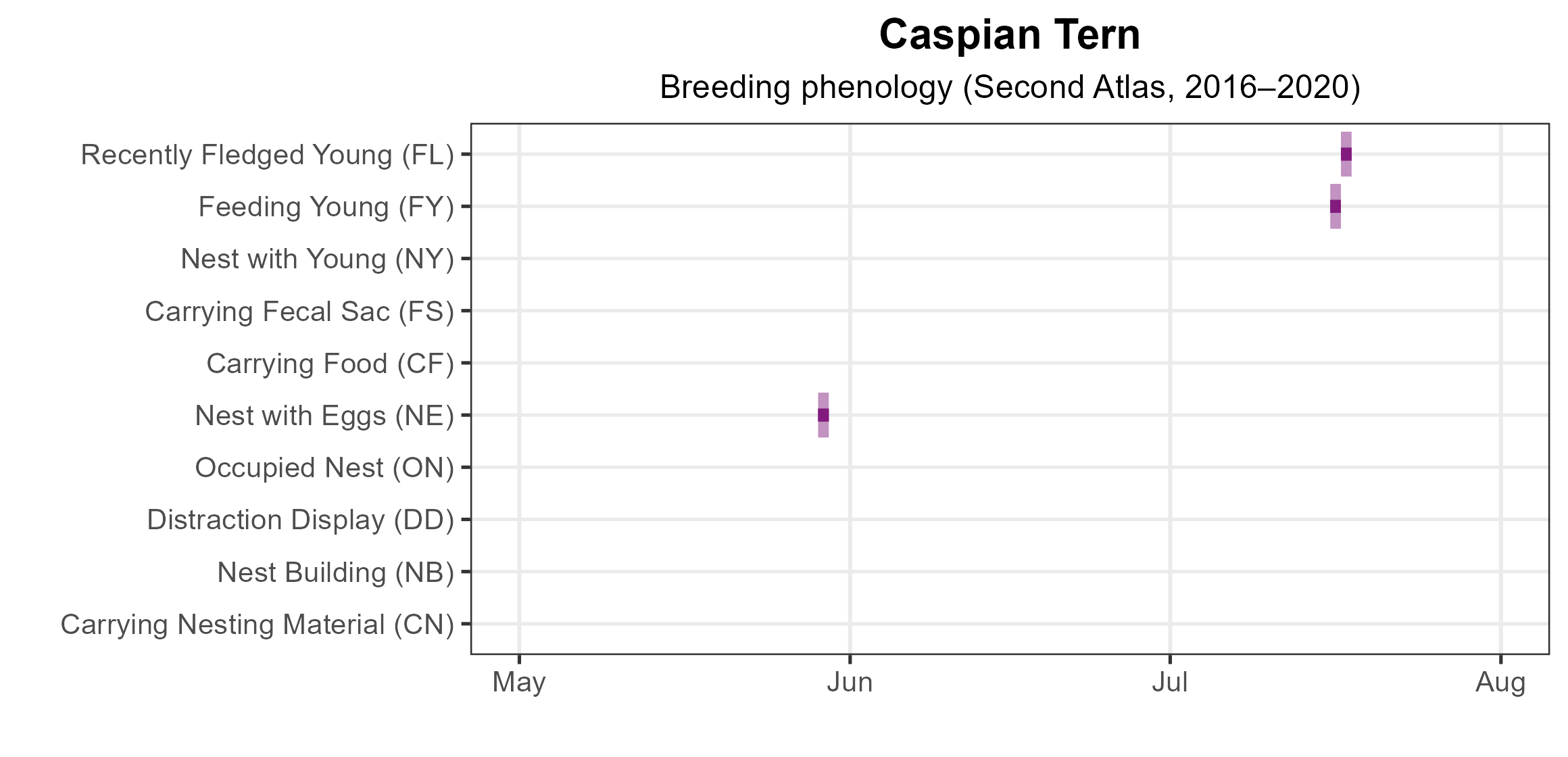

There were few observations of this rare species’ breeding behaviors. One nest with eggs was observed on May 29, and young were observed on July 16 and 17 (Figure 3). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Caspian Tern, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Caspian Tern breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Caspian Tern breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Caspian Tern phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

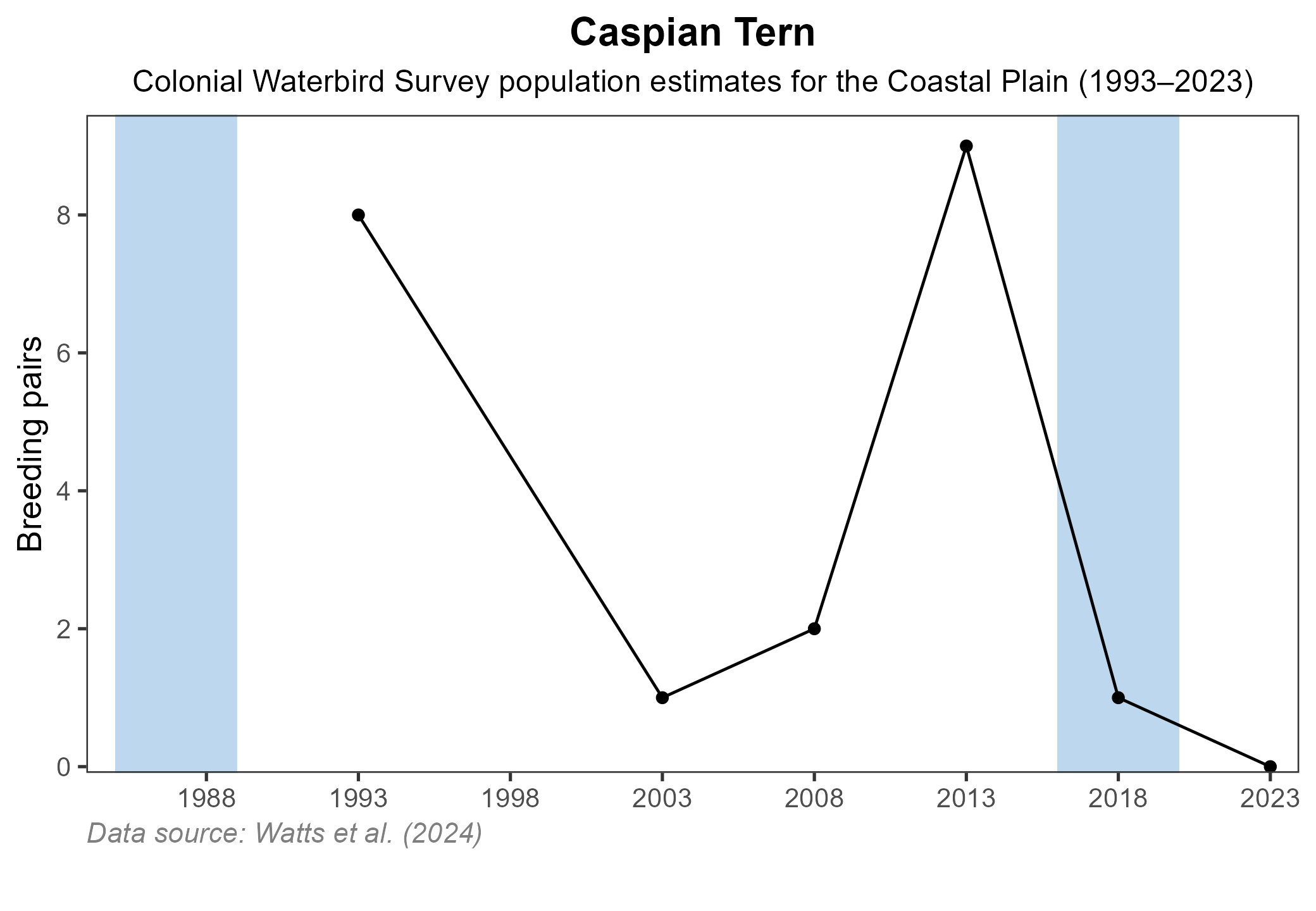

The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys show that the known breeding population has remained fewer than 10 pairs since 1993, and only one pair was observed on surveys in 2018 (Watts et al. 2019). No breeders were found in 2023 (Watts et al. 2024; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Caspian Tern population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Caspian Tern has a minimal presence as a breeding bird in Virginia and may be declining in the state. Nonetheless, it is not a species of concern in Virginia. As a colonial-nesting species, its populations are vulnerable to disturbance and loss of nesting sites. Its shoreline habitat can be lost to rising sea levels or human activity. Caspian Terns can be protected by restricting disturbance and promoting public awareness around their nesting sites.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Inc. Lynchburg, VA.

McNair, D. B. (2000). The breeding status of Caspian Terns in the Southeastern United States (Mississippi to Virginia). Florida Field Naturalist 28: 12–21.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2014). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Weske, J. S., R. B. Clapp, and J. M. Sheppard (1977). Breeding records of Sandwich and Caspian Terns in Virginia and Maryland. The Raven 48.