Introduction

The Brown-headed Nuthatch, known for its distinctive calls reminiscent of a squeaky toy or rubber ducky, is a diminutive cavity-dwelling bird that inhabits pine woodlands. This species is one of few songbirds totally endemic to the United States. Its presence is closely tied to pine savanna with an open understory, where it relies on mature pines and snags for nesting (Slater et al. 2021). In Virginia, they are associated with eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), shortleaf pine (Pinus echinate), and Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) (Shoch et al. 2020) and are often found in the pine component of mixed-pine hardwood forests (Jeffrey Walters, personal communication).

The Brown-headed Nuthatch population in Virginia is also almost at the northern edge of its range, which encompasses pine woodlands in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions of the southeastern U.S. from Texas east to Florida and north to Delaware. Within the Commonwealth, the species has expanded its range in Virginia since the 1960s, gradually colonizing new habitats in the Piedmont and Mountains and Valleys regions (Shoch et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Brown-headed Nuthatches are most likely to occur in the Coastal Plain region and more so along coastlines (Figure 1). These areas have a high concentration of loblolly pine, one of the pine species on which this bird relies. In Virginia, they prefer nest sites close to mature pines with fewer oaks (Weiss 1999). They are also highly likely to occur in the Great Dismal Swamp (cities of Chesapeake and Suffolk) and in scattered areas throughout the central and southern Piedmont region.

The species is more likely to occur in a block as the amount of shrubland cover (young forest) increases, but predicted occurrence is also slightly positively associated with the number of different habitat types in a block. In contrast, the species is slightly negatively associated with agricultural and developed lands. Based on the model, it is also less likely to occur in a block as the amount of forest cover increases; however, it is important to note that “forest” in this model encompasses all forest types within the state, not specifically the pine forests Brown-headed Nuthatches inhabit. Thus, this relationship may be influenced by the environmental variables that could be included in the model.

Additionally, the distribution of this species during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Brown-headed Nuthatch breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

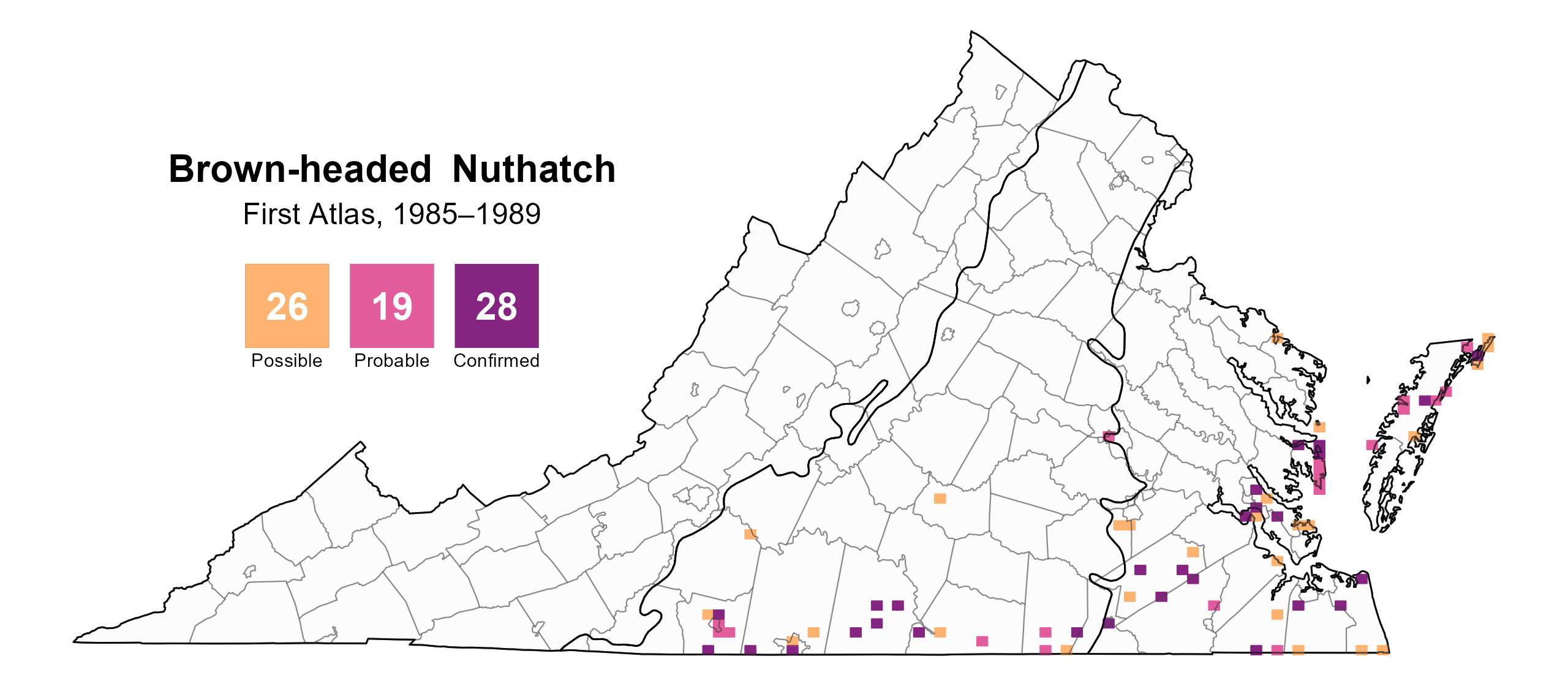

Brown-headed Nuthatches were confirmed breeders in 102 blocks and 42 counties (Figure 2). Although primarily found in the Coastal Plain region prior to the 1960s (Shoch et al. 2020), during the Second Atlas, the species was observed at more than 26 sites in the Piedmont region and 12 sites in the Mountains and Valleys region, mostly in recreational and residential areas with Virginia pine and eastern white pine (based on additional evidence outside the Atlas; see Shoch et al. 2020). The increase in observations of confirmed and probable breeders from the First Atlas to the Second Atlas is indicative of the species’ expansion within the Piedmont region and into the Mountains and Valleys region (Figures 2 and 3; Shoch et al. 2020).

The populations observed in the Mountains and Valleys region include those at South Holston Lake (Washington County), near Radford (Pulaski County), near Blacksburg (Montgomery County), and in Roanoke city. Breeding was confirmed in the Piedmont region as far north and inland as Fort Walker (Caroline County). In 2020, a single bird was discovered at Mountain Run Lake Park (Culpeper County), although breeding could not be confirmed.

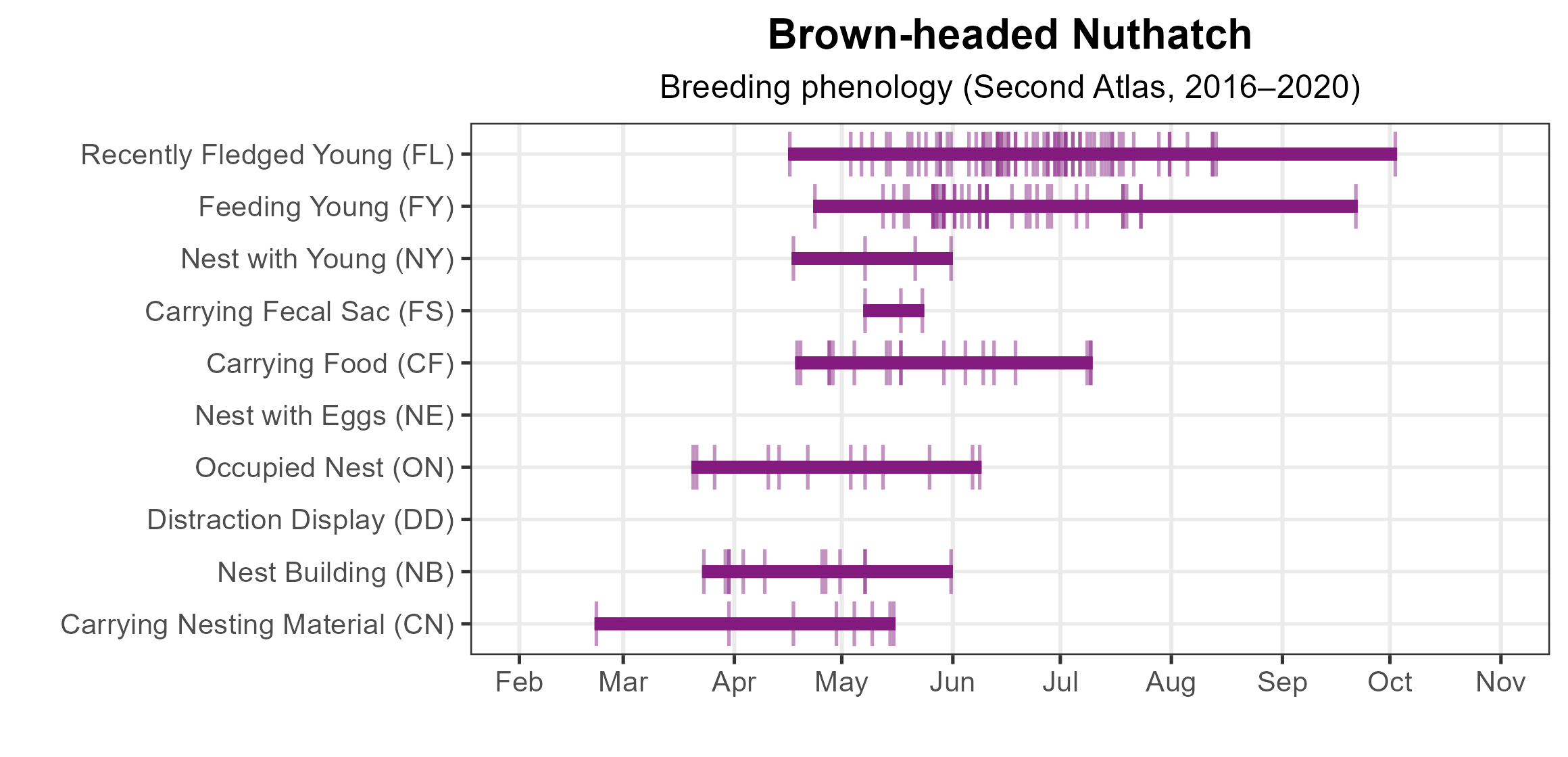

Notably, nest building was observed as early as February (Figure 4). However, Brown-headed Nuthatches will excavate cavities at any time of year (Slater et al. 2021), so this may not indicate a true expansion of their breeding activity period. Confirmed breeding was documented from March 20 (occupied nests) to October 2 (recently fledged young).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Brown-headed Nuthatch breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Brown-headed Nuthatch breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Brown-headed Nuthatch phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Brown-headed Nuthatch relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area, but it was generally high throughout most of the Coastal Plain region (Figure 5). However, the extremely local and pine-dependent nature of the species means that different modeling approaches involving more specific habitat data that include prevalence of pines and midstory and canopy densities may be necessary to capture its true abundance.

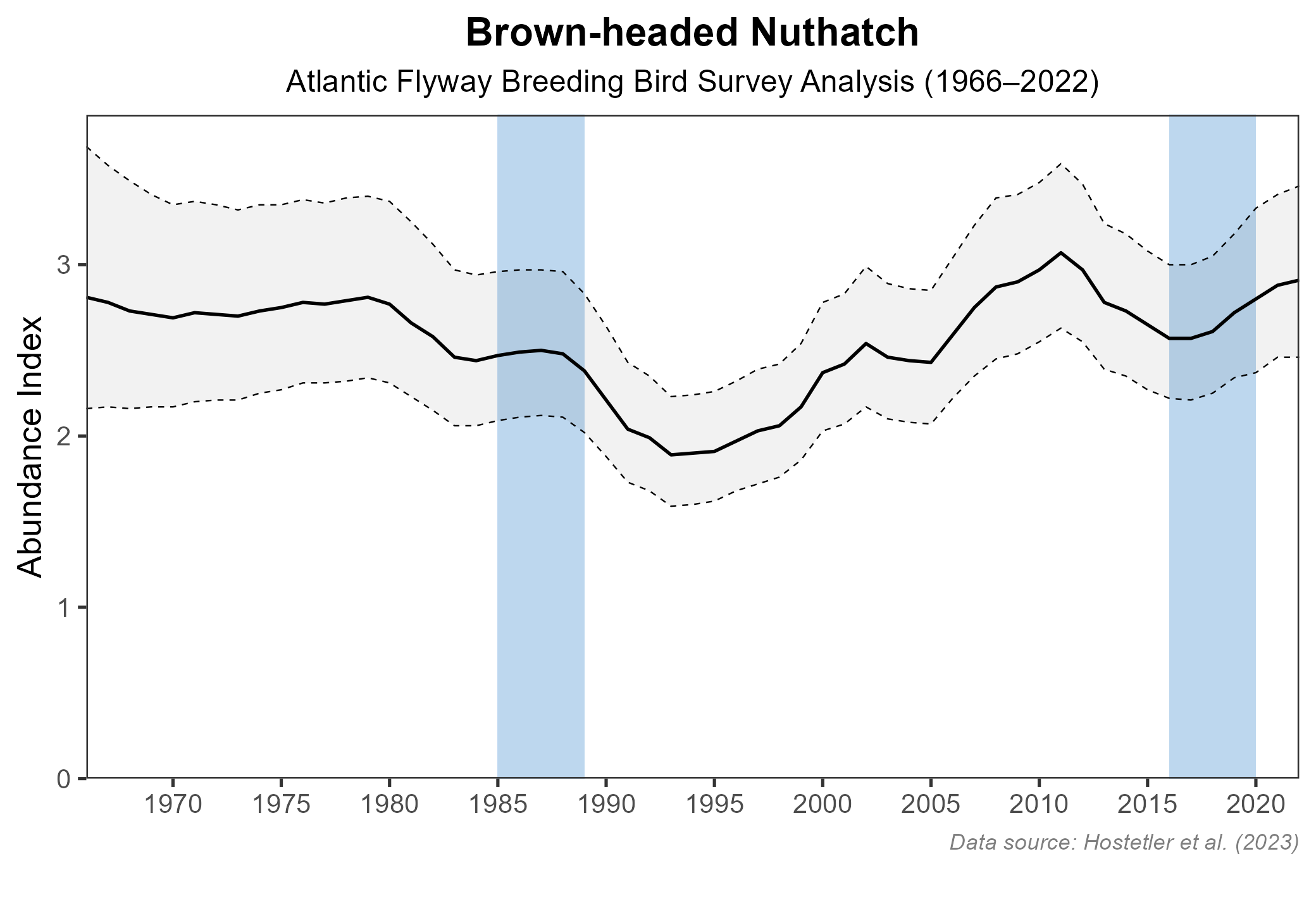

The total estimated population of Brown-headed Nuthatches in the state is approximately 67,000 individuals (with a range between 30,000 and 151,000). Although the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) population data for Virginia do not provide a credible trend, at the Atlantic Flyway scale, BBS data showed a nonsignificant increase of 0.08% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6). Between Atlas periods, at this regional scale, the BBS data showed a nonsignificant increase of 0.15% per year from 1987–2018. The range expansion of the Brown-headed Nuthatch within Virginia is likely tied to an increasing population size, which may not be captured within the broader Atlantic Flyway trend.

Figure 5: Brown-headed Nuthatch relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Brown-headed Nuthatch population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Although the Brown-headed Nuthatch’s population has expanded within the state, it can be vulnerable to local extirpation. Other states have reintroduced the species with success in areas where it was historically present (Heath-Acre et al. 2023).

In the core of its range, the Brown-headed Nuthatch is associated with the same habitats as Bachman’s Sparrow (Peucaea aestivalis) and Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis) (Engstrom 1993). Bachman’s Sparrow has not been documented in Virginia since 2002, and the Red-cockaded Woodpecker currently inhabits a small area in Virginia; management for either of these species, particularly by maintaining mature pine stands with prescribed fire, can also benefit Brown-headed Nuthatches (Wilson et al. 1995).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Cox, J. A., and G. L. Slater (2007). Cooperative breeding in the Brown-headed Nuthatch. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1676/06-006.1.

Engstrom, R. T. (1993). Characteristic mammals and birds of longleaf pine forests. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 18:127–138. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL, USA.

Heath-Acre, K. M., S. W. Kendrick, F. R. Thompson III, T. W. Bonnot, B. Davidson, and J. A. Cox (2023). Survival and movements of Brown-headed Nuthatches after translocation to the Missouri Ozarks. Wildlife Society Bulletin 47:e1475. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.1475.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Shoch, D.T., C. Kessler, B. Becker, R. Dickson, and D. Bedarf (2020). Breeding range expansion of Sitta pusilla Latham (Brown-headed Nuthatch) in Virginia. Southeastern Naturalist 19:283–96. https://doi.org/10.1656/058.019.0208.

Slater, G. L., J. D. Lloyd, J. H. Withgott, and K. G. Smith (2021). Brown-headed Nuthatch (Sitta pusilla), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Weiss, V. A. (1999). Nest site selection of the Brown-headed Nuthatch in Virginia. Master’s Thesis, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. https://doi.org/10.21220/s2-hpag-fg47.

Wilson, C. W., R. E. Masters, and G. A. Bukenhofer (1995). Breeding bird response to pine-grassland community restoration for Red-cockaded Woodpeckers.” The Journal of Wildlife Management 59:56–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/3809116.