Introduction

A trip to nearly any waterway at any time of year in Virginia may produce an encounter with a Belted Kingfisher, fondly referred to as “Becky” by researchers who study this species. They are frequently heard giving their emphatic rattling call, while zipping along the water’s edge in search of aquatic prey, such as small fish, crayfish, and sometimes frogs. In riparian forest habitat, they tend to nest in earthen burrows that they excavate in eroded creek banks, pond edges, and even sandbanks so that they are close to open water for feeding (White 2007; Kelly et al. 2020). Interestingly, they have also been documented using man-made structures, such as saw dust piles and sand and gravel pits, when adequate nesting sites are not available (Prose 1985).

Breeding Distribution

Modeling limitations prevented the development of distribution models for the Belted Kingfisher (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

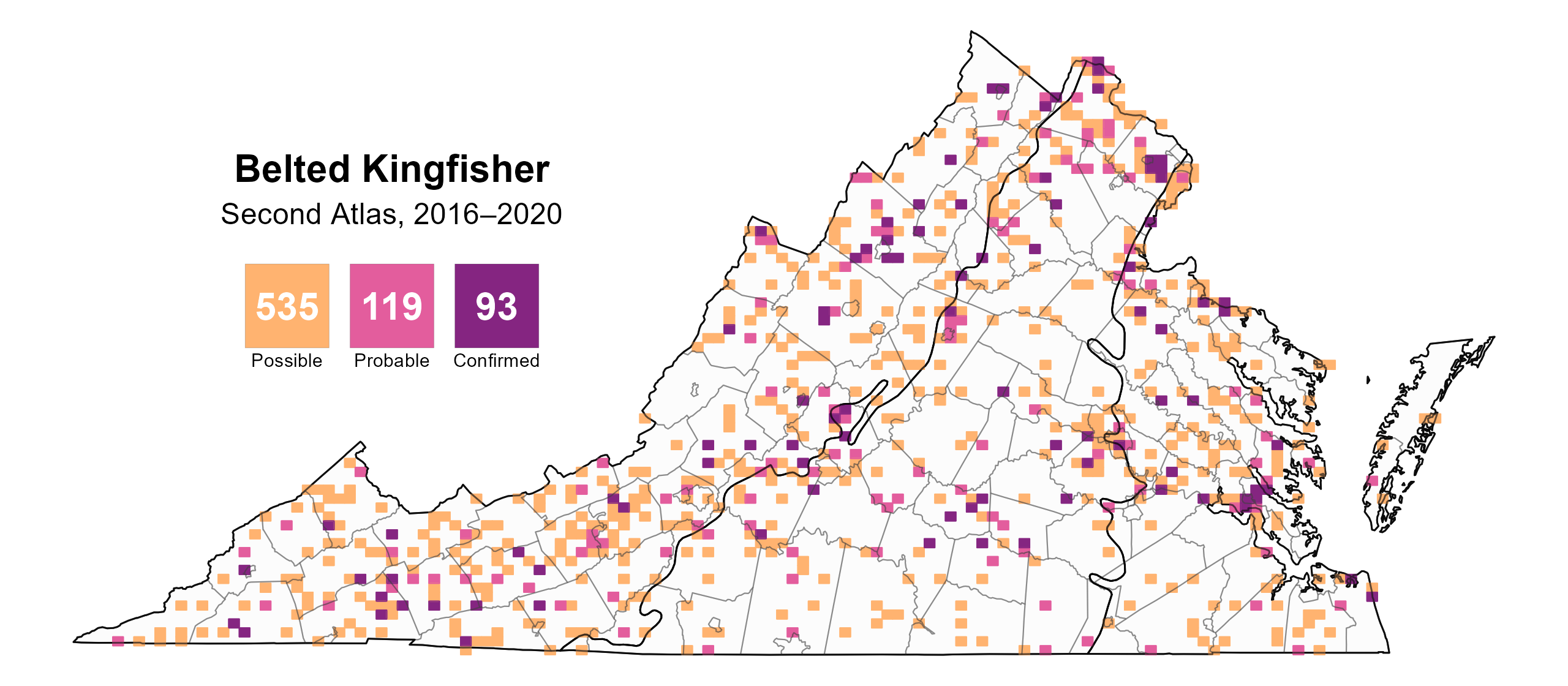

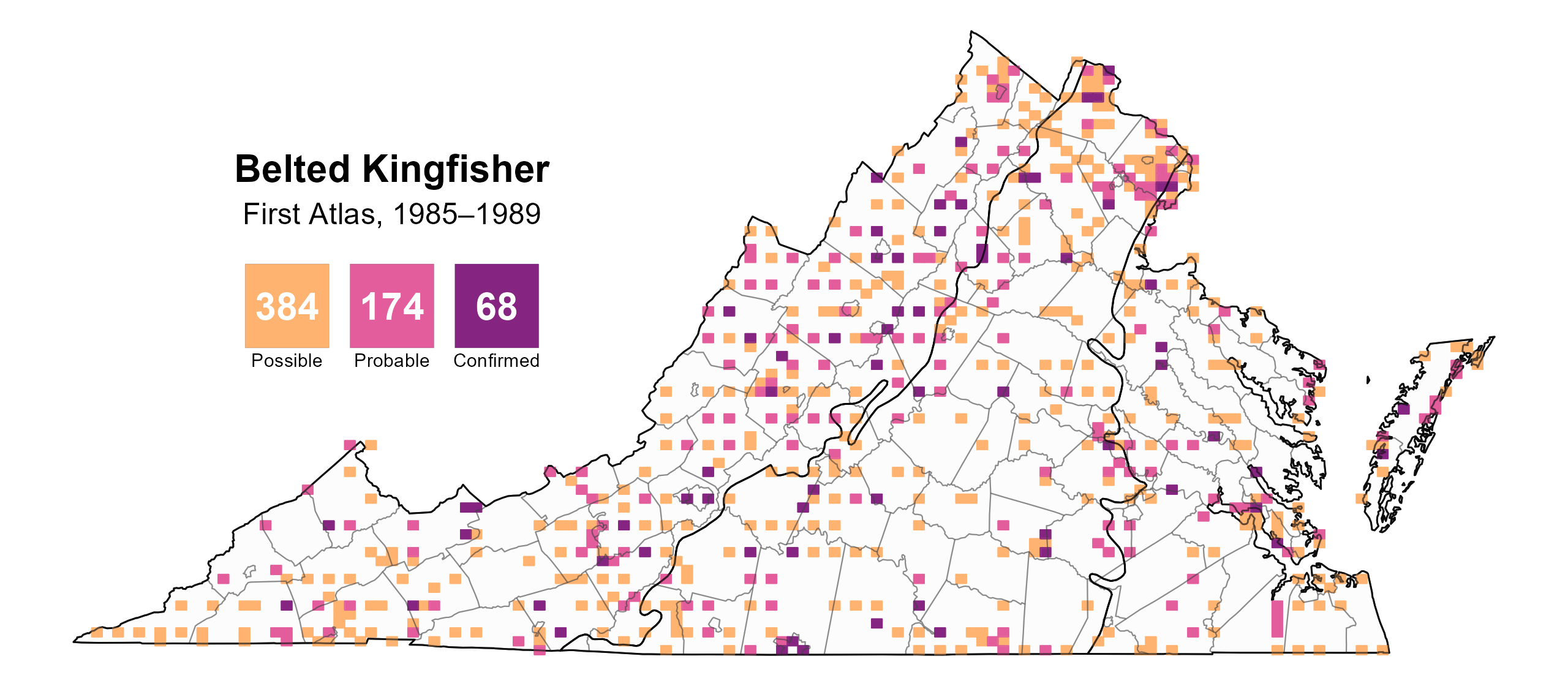

Belted Kingfishers were confirmed in 93 blocks and 54 counties and determined to be probable breeders in an additional 29 counties (Figure 1). This species was found throughout the state, although nearly 80% of the blocks it occupied were in the Mountains and Valleys and Piedmont regions. The distribution of breeding observations was generally similar between Atlas periods, with kingfishers being reported in roughly 20% more blocks during the Second Atlas (Figures 1 and 2) despite a negative population trend (see Conservation section). This uptick was likely due to greater survey effort during the more recent Atlas.

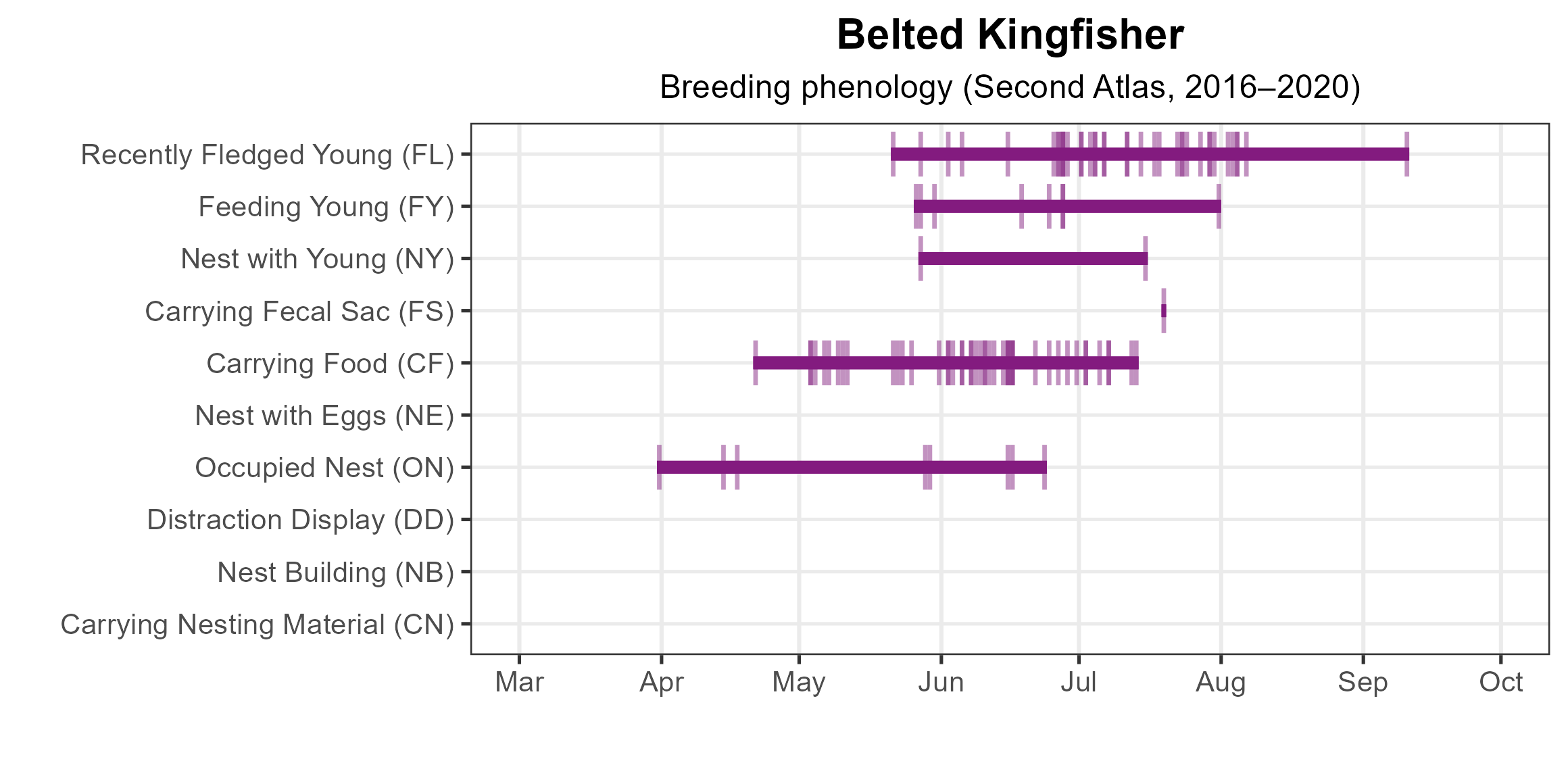

Occupied nests were the earliest observed evidence of breeding (March 31), while recently fledged young were observed between May 21 and September 10 (Figure 3). Carrying food was the most frequently documented breeding behavior throughout much of the season (April 21 – July 13). Atlas volunteers documented a small number of nest burrows in the banks of rivers, creeks, lakes and ponds, as well as within a quarry and even in a large pile of dirt near a pond (Rockingham County).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Belted Kingfisher breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Belted Kingfisher breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Belted Kingfisher phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

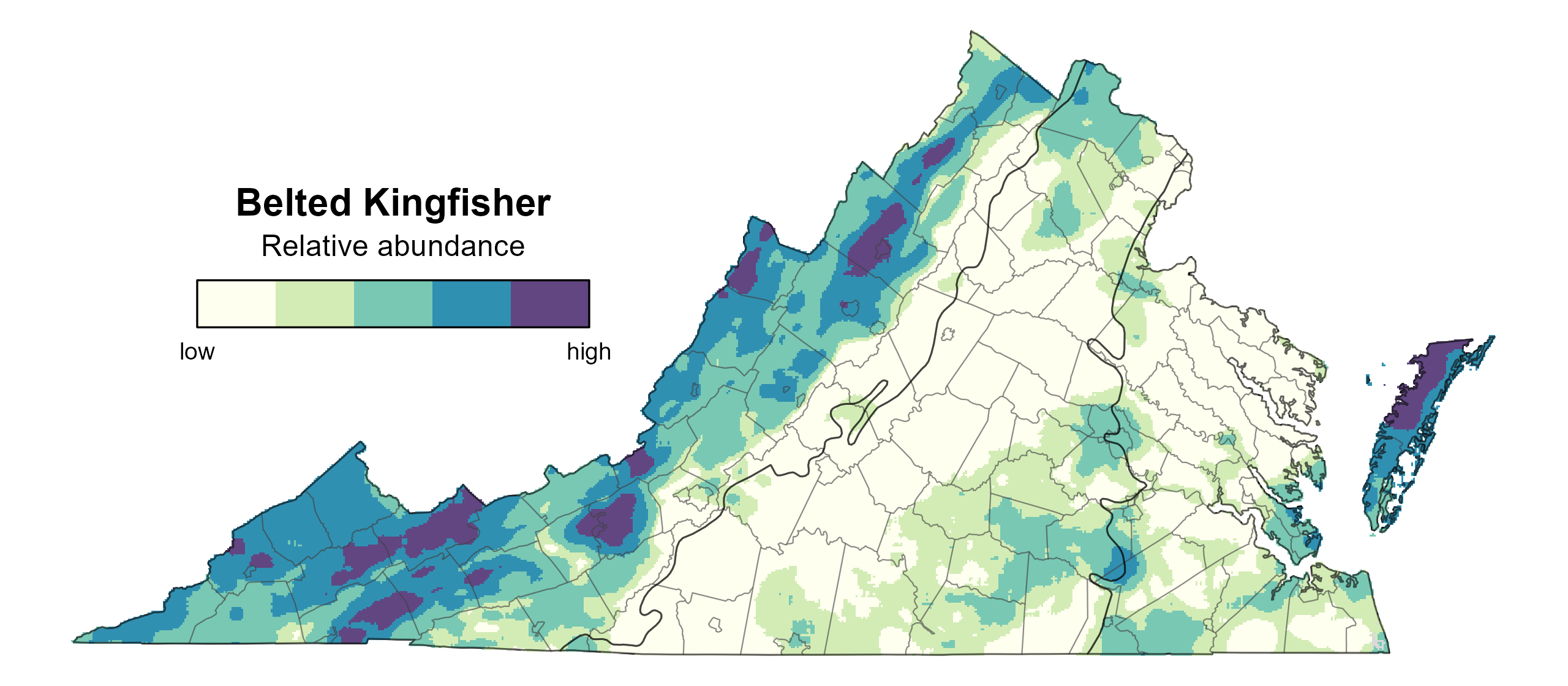

Belted Kingfisher relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the Mountains and Valleys region and on the Eastern Shore (Figure 4). It was predicted to be moderately high in areas of the northern and southeastern Piedmont region and the southeastern Coastal Plain but was otherwise low in the two regions.

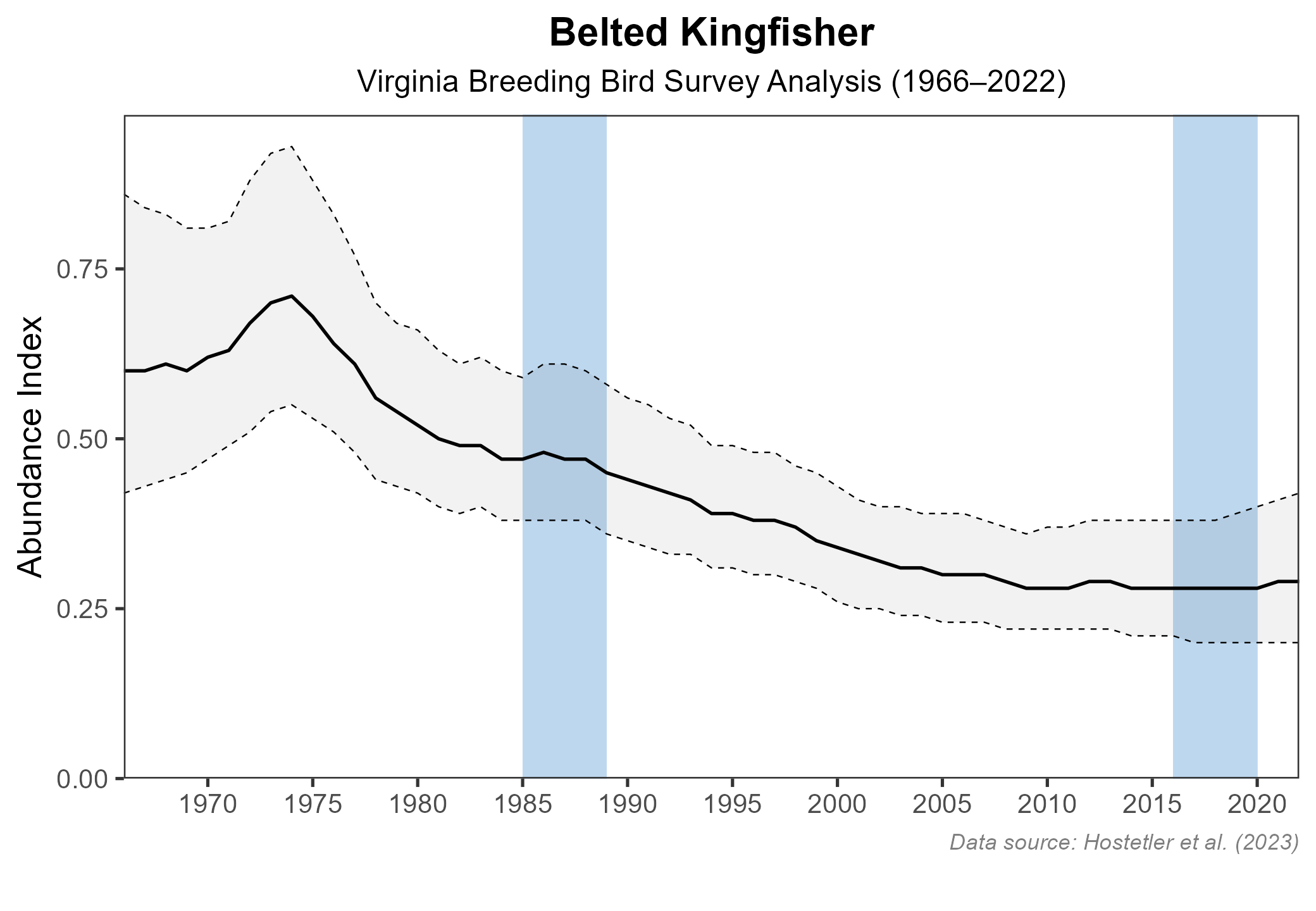

The total estimated Belted Kingfisher population in the state is approximately 13,000 individuals (with a range between 7,000 and 26,000). Based on the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), the Belted Kingfisher population declined by a significant 1.28% annually from 1966–2022 in Virginia, and between Atlas periods, its population decreased by a similar significant rate of 1.73% per year from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5).

Figure 4: Belted Kingfisher relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 5: Belted Kingfisher population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Belted Kingfishers are exhibiting steady population declines in Virginia and throughout their range (Kelly et al. 2020; Hostetler et al. 2023), prompting their inclusion in the Virginia 2025 Wildlife Action Plan as a Tier III (High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need (VDWR 2025).

Although the reasons for this decline are not clear, the species’ dependence on waterbodies as a foraging source draws a connection to water quality as a clear line of investigation. A study along the South River in Augusta and Rockingham Counties found no impact of mercury contamination on their reproductive success (White 2007). However, mounting evidence shows that kingfisher species may be sensitive to microplastics contamination in rivers and streams (Wayman et al. 2024), suggesting an important direction for future conservation research and assessment in Virginia.

Like the Northern Rough-winged Swallow (Stelgidopteryx serripennis) and Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia), the Belted Kingfisher is a bank-dependent species that has also adapted to nesting in habitats created by humans (Kelly et al. 2020). A mid-1990s survey of exposed banks along tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay found the species to be widely distributed among the major rivers in Virginia, albeit in low densities totaling 151 pairs (Bryan Watts, unpublished data). This survey by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) at the College of William and Mary provides a baseline for comparison against future surveys. A repeat of the survey would enable evaluation of changes to this segment of the kingfisher population and to its habitat supply, as river and stream banks are susceptible to development, erosion and erosion control efforts. A 2022 CCB survey of a small sample of quarries in the Piedmont region and northwestern Virginia also documented nesting kingfishers (Bryan Watts, unpublished data). A broader evaluation of the species’ use of quarries in Virginia is warranted to assess their importance and whether they support successful breeding.

Because population declines may be driven by factors outside of the breeding season, investigation of the Belted Kingfisher’s wintering ecology, with a focus on identifying resources necessary for its overwinter survival, could be important (VDWR 2025). The species is present year-round in the Commonwealth (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), but most U.S. populations are partial migrants (Kelly et al. 2020). Investigating the migratory status of Virginia’s Belted Kingfishers would clarify whether research during the winter season should take place beyond the Commonwealth (VDWR 2025).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Kelly, J. F., E. S. Bridge, and M. J. Hamas (2020). Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.belkin1.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Prose, B. L. (1985). Habitat suitability index models: Belted Kingfisher. Biological Report 82(10.87). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C., USA. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-I49-PURL-LPS101740/pdf/GOVPUB- I49-PURL-LPS101740.pdf.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wayman, C., M. González-Pleiter, F. Fernández-Piñas, E. L. Sorribes, R. Fernández-Valeriano, I. López-Márquez, F. González-González, and R. Rosal (2024). Accumulation of microplastics in predatory birds near a densely populated urban area. Science of the Total Environment 917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170604.

White, A. E. (2007). Effects of mercury on condition and coloration of Belted Kingfishers. Master’s Thesis. Paper 1539626860. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0956-qp64.