Introduction

The enigmatic American Woodcock is a shorebird that breeds in forested landscapes, where it is found in young forests and overgrown shrubby fields. It goes largely unnoticed by most Virginians, nesting directly on the ground and using its mottled brown and black plumage to hide from predators and human eyes. American Woodcocks are seen and heard most often during spring evenings, when males give spectacular breeding displays that include a characteristic peent vocalization and flying high into the air and floating to the ground like a leaf on the wind (McAuley et al. 2020; Seamans and Rau 2024).

Breeding Distribution

Modeling limitations prevented the development of occupancy models for the American Woodcock (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Please see the Breeding Evidence section for information on breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

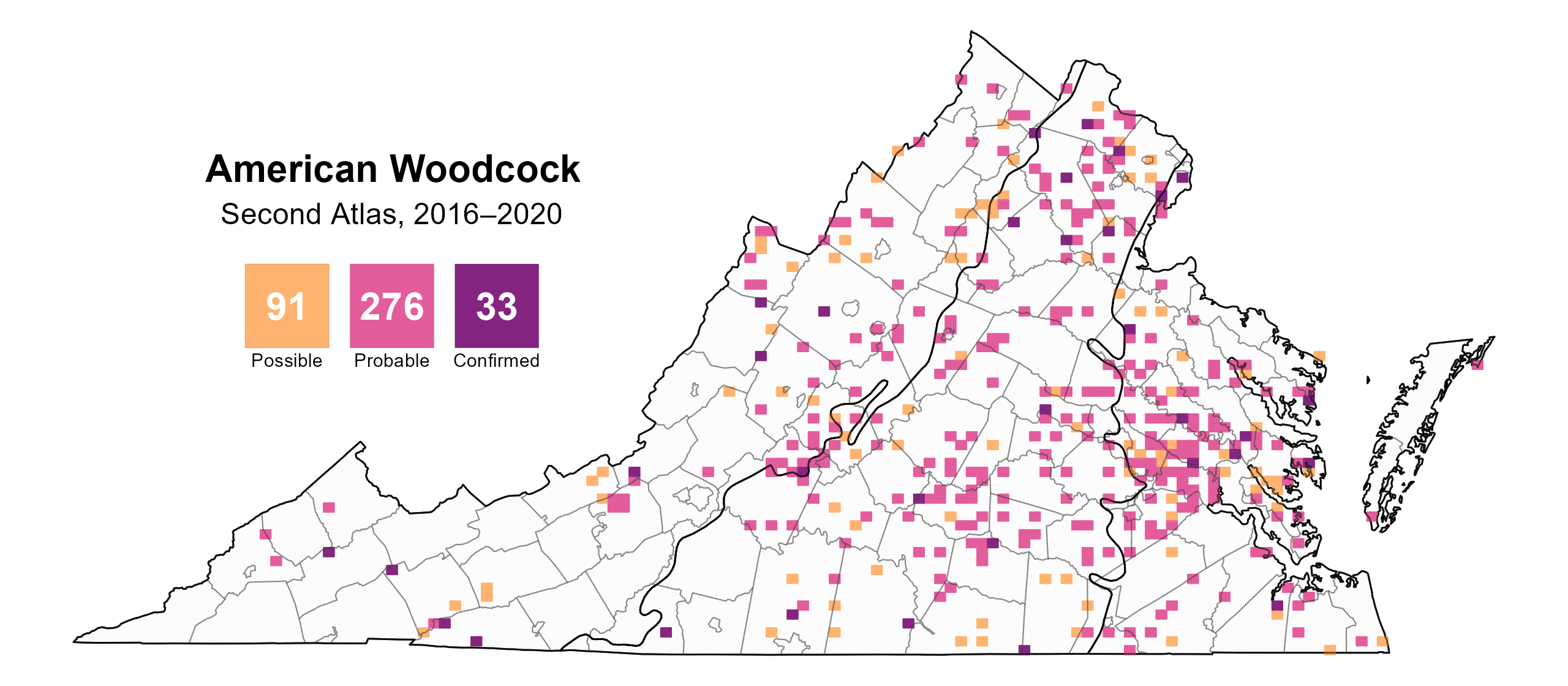

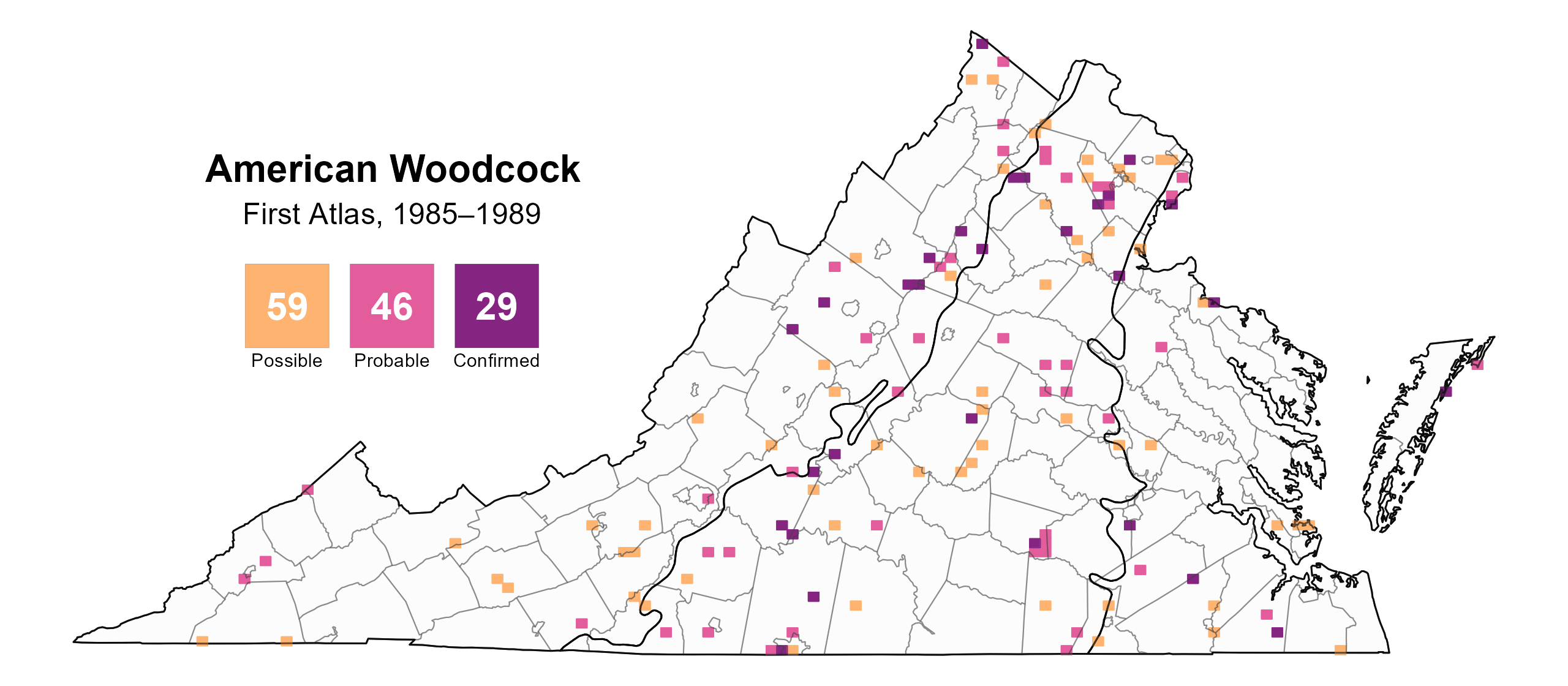

American Woodcocks were distributed across the state as confirmed breeders in 33 blocks and 27 counties and as probable breeders in 52 additional counties (Figure 1). The large number of probable breeding records is a function of this species being most easily detected by both sight and sound during its conspicuous courtship displays. Breeding confirmations are hard to obtain, given the placement of nests in the leaf litter and difficulty in detecting fledged young. Breeding observations were generally greater in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions and were scattered in the Mountains and Valleys region. Although more breeding observations were recorded during the Second Atlas than during the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2), this is not indicative of an increase in its population, which is in decline in the state (see the Population Status section). This difference was instead likely due to greater survey effort during the Second Atlas.

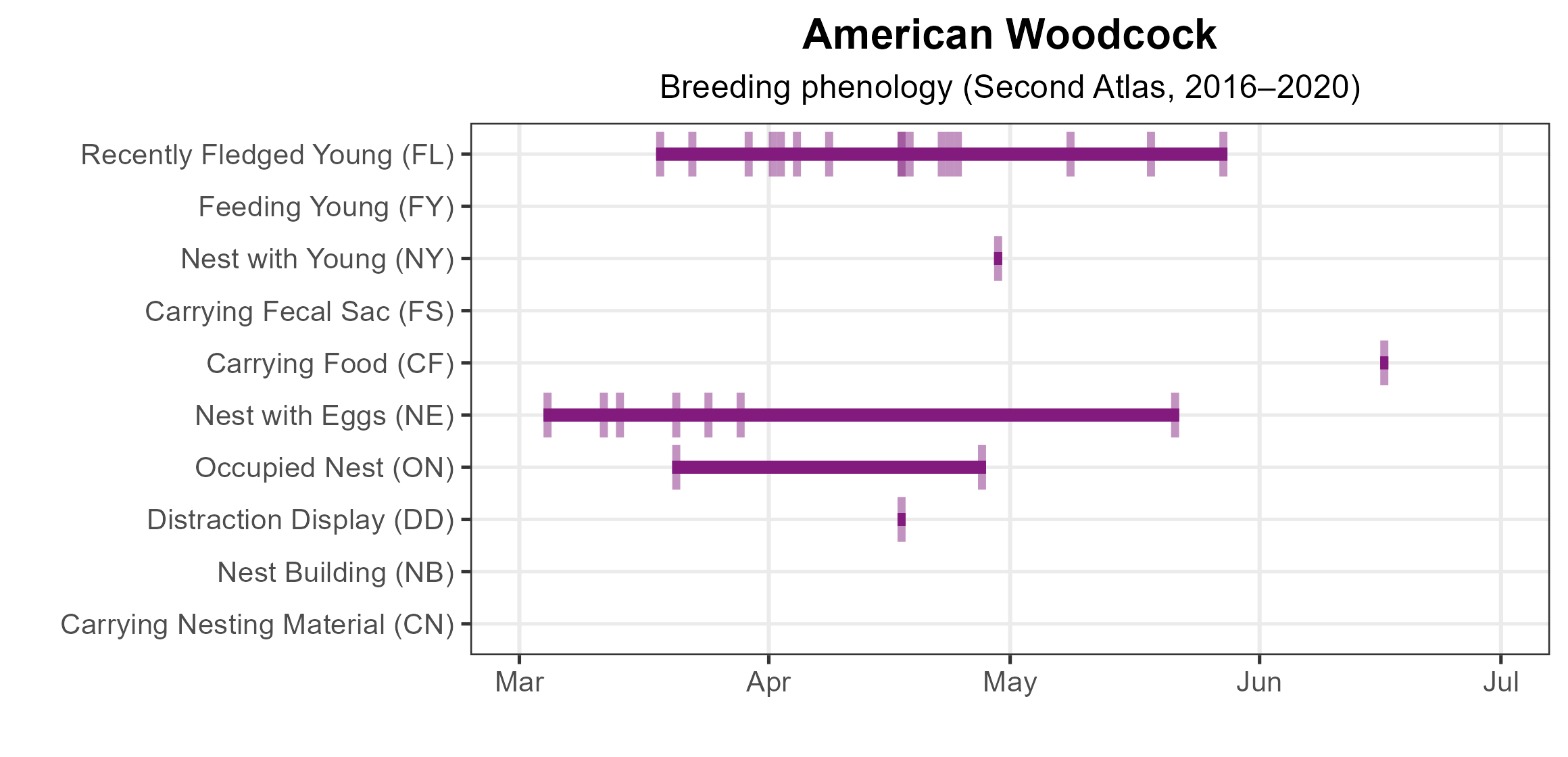

The earliest confirmation of breeding was of a nest with eggs observed on March 4; however, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) observed several radio-equipped American Woodcocks on nests with eggs in mid- to late-February during a migration study from 2019 to 2022 (Gary Costanzo, personal communication). Atlas volunteers reported nests with eggs through May 21. Recently fledged young were reported between March 18 – May 27.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: American Woodcock breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: American Woodcock breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: American Woodcock phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

A low number of detections in the Atlas point count data prevented the development of abundance models for the American Woodcock. Additionally, given that American Woodcocks are semi-nocturnal and not regularly observed during the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), credible BBS population trends could not be calculated. Since the late 1960s, American Woodcock population status has been monitored by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, using specialized singing ground surveys. Seamans and Rau (2024) reported that the 10-year average American Woodcock singing ground count for Virginia declined by a significant 4.12% from 1968 to 2022.

Conservation

The 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan includes this species as a Tier I (Critical Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need based on its declining trend and small Virginia population (VDWR 2025). Although the American Woodcock has a broad distribution in the state, difficulty in differentiating migrants from breeding birds may mask the actual size of its breeding population because courtship behaviors can be displayed while individuals are migrating northward between January and March (Gary Costanzo, personal communication). As 82% of all courtship observations during the Second Atlas took place during this migratory period, the breeding population may be less widely distributed (and therefore smaller) within Virginia than it appears in Figure 1. In fact, the VDWR estimates that there are currently fewer than 1,000 breeding pairs within the Commonwealth (Gary Costanzo, personal communication).

American Woodcock population declines may be driven by loss of breeding habitat, such as shrubby fields and young forests; thus, focusing on managing and maintaining these early and mid-successional habitats in the state will be important for its conservation (Kelley et al. 2008; McAuley et al. 2020; Seamans and Rau 2024). Timber management that results in early to mid-successional forest stages interspersed with other successional stages is critical to providing the range of habitat conditions necessary to support breeding (VDWR 2025). Public lands have a role to play in such forest management. Low recruitment of new birds into the American Woodcock population may be contributing to its decline in Virginia (VDWR 2025). Factors affecting recruitment such as nest survival (including nest predation rates and nest predators), as well as potential ways to improve nest survival, merit further study (VDWR 2025).

The conservation outlook for American Woodcock is benefiting from regional approaches that have resulted in a Conservation Plan (Kelley et al. 2008), collaborative multi-state research projects, and a Young Forest Initiative working to protect, restore, and enhance young forest and shrubland.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Kelley, J., S. Williamson, and T. R. Cooper (Editors) (2008). American Woodcock conservation plan: a summary of and recommendations for woodcock conservation in North America. Wildlife Management Institute. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/woodcock-conservation-plan-migratory-birds.pdf.

McAuley, D. G., D. M. Keppie, and R. M. Whiting Jr. (2020). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amewoo.01.

Seamans, M.E., and R.D. Rau. 2024. American woodcock population status, 2024. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, MD, USA.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.