Introduction

The Downy Woodpecker, Virginia’s smallest woodpecker, is an abundant permanent resident in the Commonwealth. A high pik precedes their arrival at backyard feeders, where they are a common sight. They are an adaptable bird at home in nearly any tree habitat. Of the breeding woodpeckers in Virginia, Downy Woodpeckers use the least mature forests for nesting (Conner and Adkisson 1977).

Their scientific epithet pubescens and common name “downy” refer to soft texture of their white back feathers, a contrast to the hairlike feathers in the same place on the Hairy Woodpecker (Dryobates villosus) (Jackson and Ouellet 2020). The plumage of the Downy Woodpecker mimics that of the Hairy Woodpecker despite the two species not being closely related. This convergence may allow Downy Woodpeckers to take advantage of the larger size and aggressive nature of Hairy Woodpeckers in a form of interspecific social dominance mimicry (Prum and Samuelson 2012).

Breeding Distribution

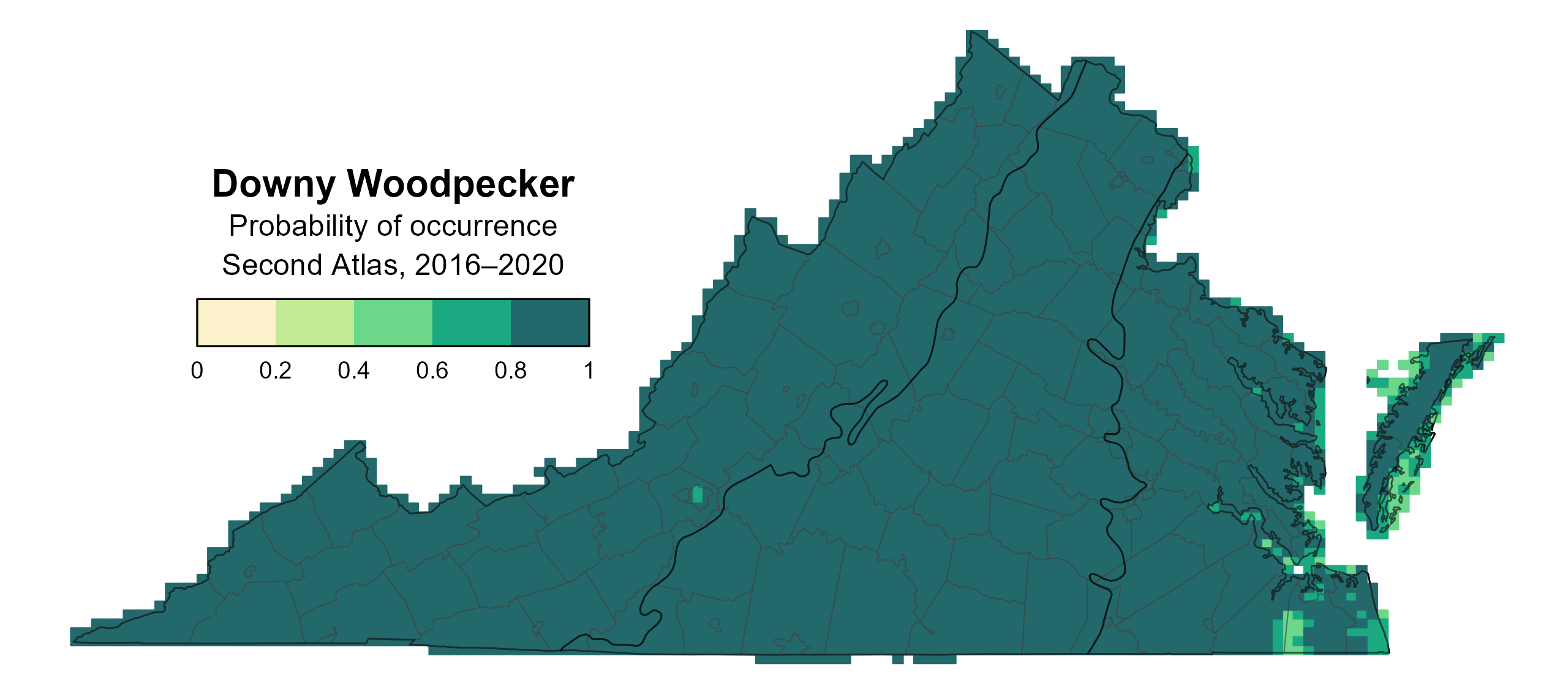

Downy Woodpeckers occur uniformly across all regions of the state (Figure 1). Anywhere there is a patch of trees, they are likely to be found. The likelihood of this species occurring in a block increases with the amount of forest edge habitat, and their occurrence is slightly positively associated with forest cover as well. Downy Woodpeckers are generalists with a broad range and use of habitats, from urban woodlots to deep forests (Jackson and Ouellet 2020).

Their distribution during the First Atlas and the ensuing change in distribution between Atlas periods could not be modeled due to model limitations (see Interpreting Species Accounts). For more information on their distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Figure 1: Downy Woodpecker breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Breeding Evidence

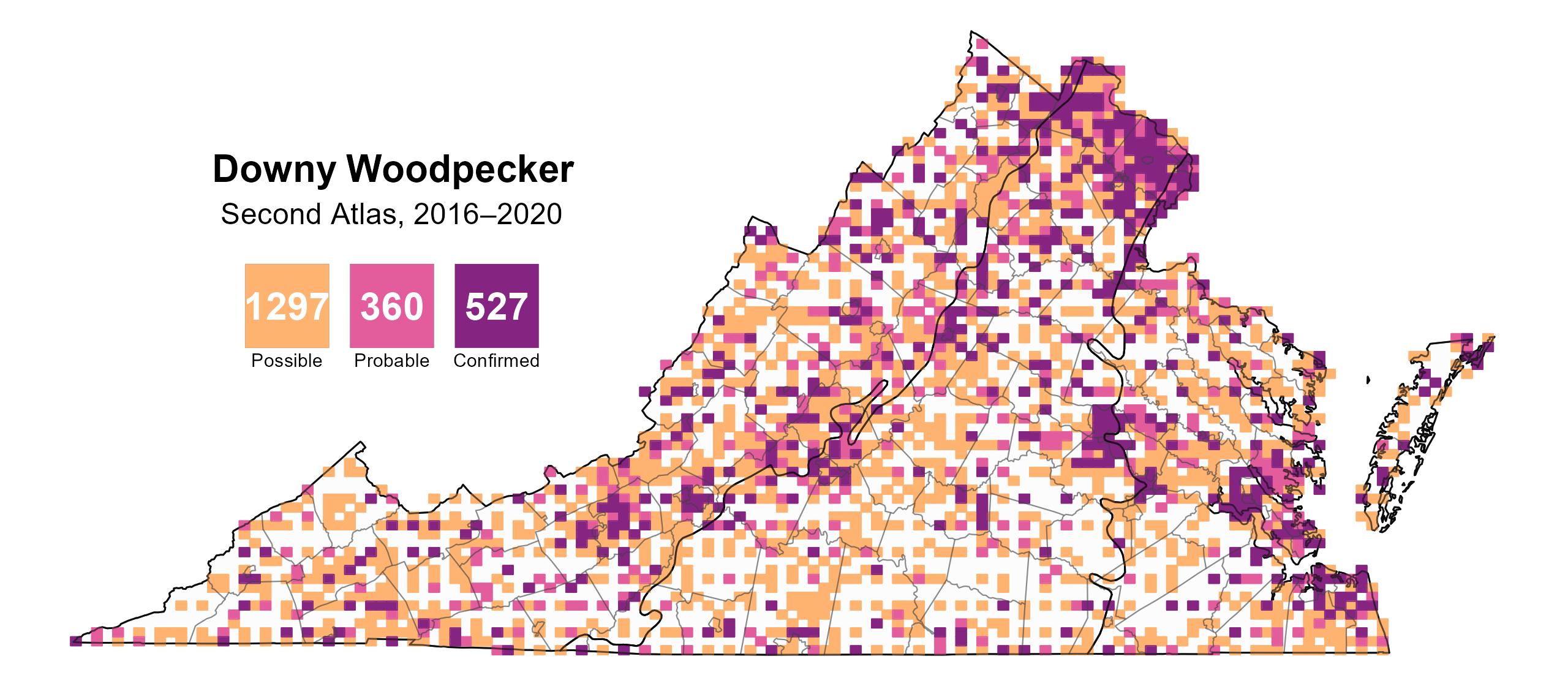

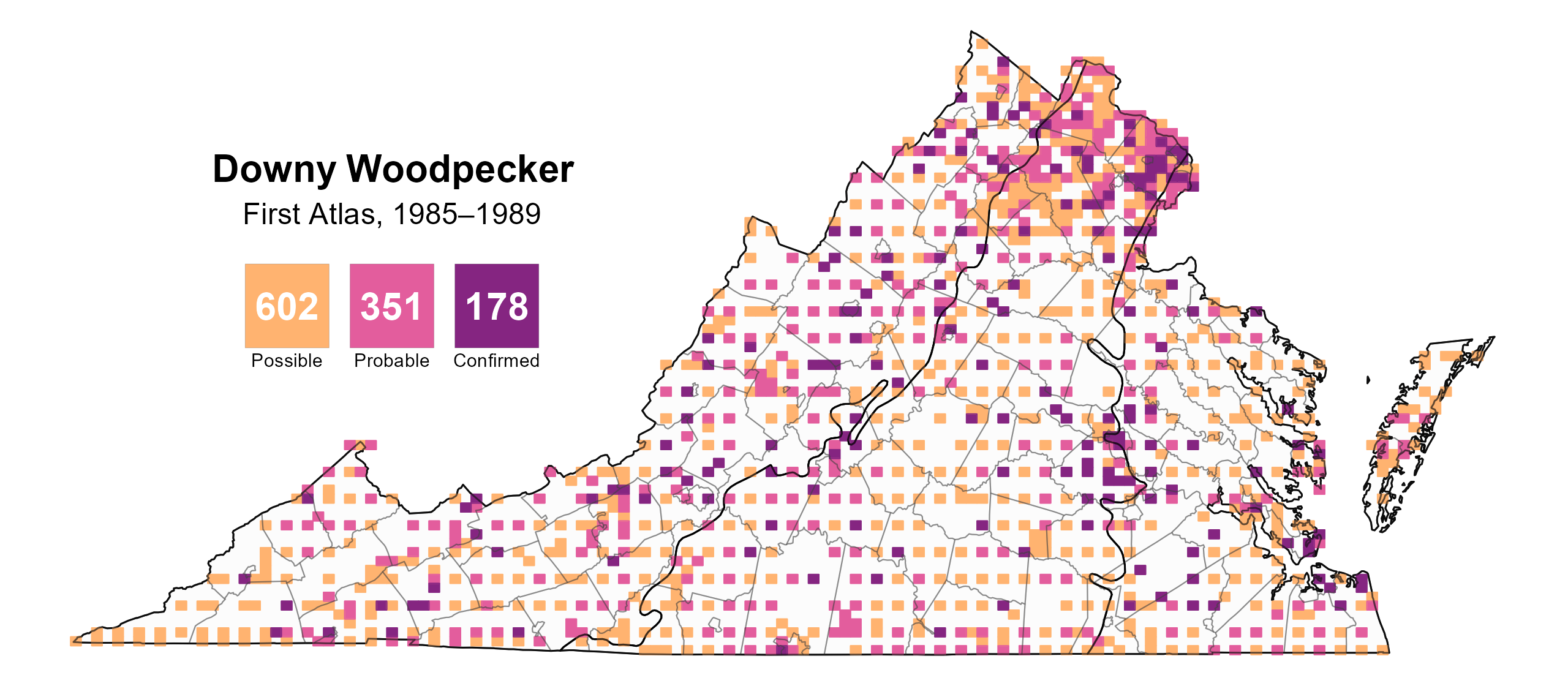

Downy Woodpeckers were confirmed breeders in 527 blocks and 109 counties and probable breeders in an additional 12 counties (Figure 2). Most of the counties missing confirmations were smaller independent cities. Breeding observations were also recorded across the state during the First Atlas (Figure 3).

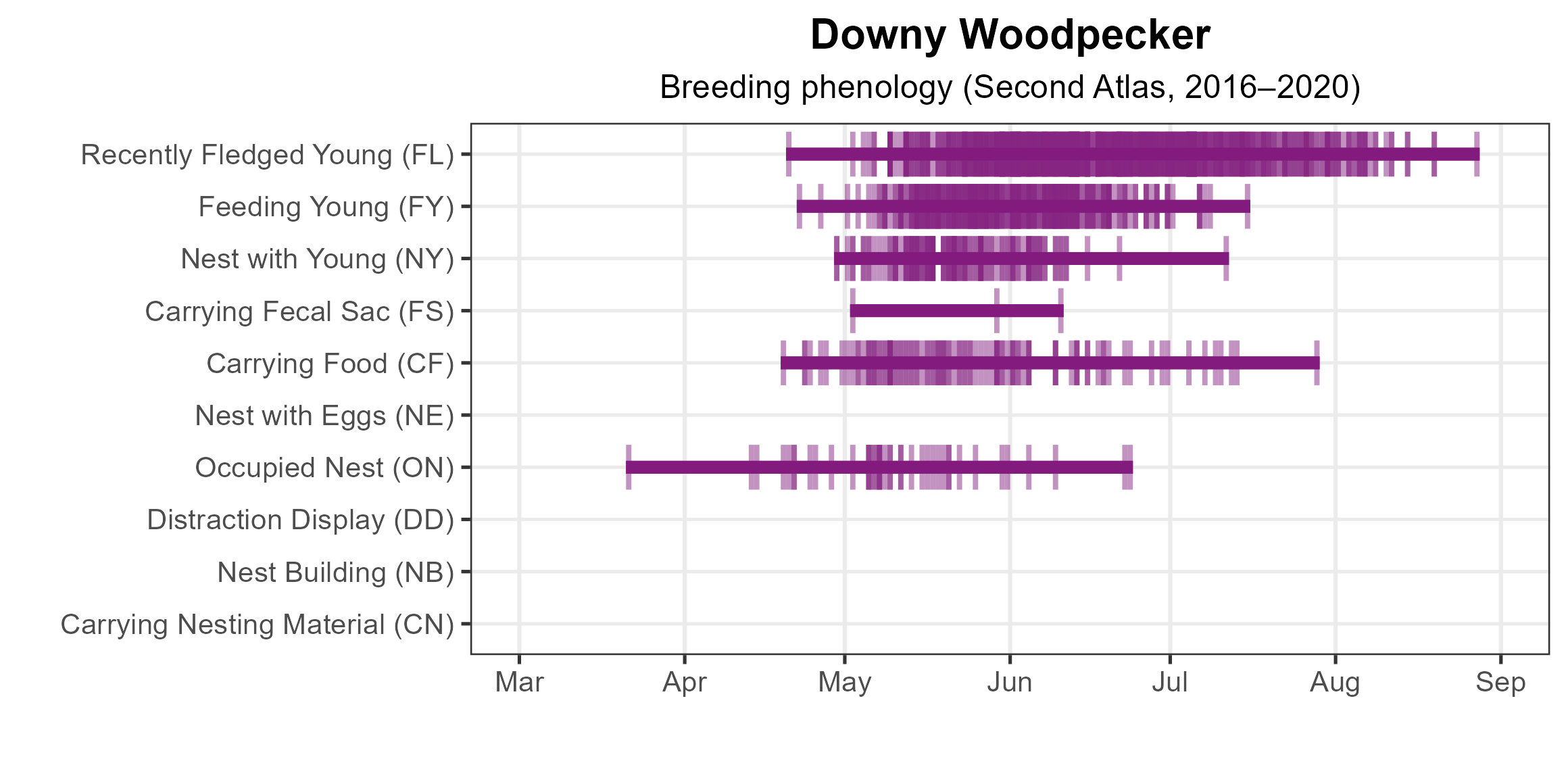

Downy Woodpeckers began occupying nests on in January 8, and fledglings appeared starting April 20 (Figure 4). Breeding continued through late August, with fledglings observed through August 27. The majority of observations were of fledglings, followed by adults feeding young. Downy Woodpecker nests can be difficult to locate in small cavities, and adults often bring young to feeders, making birdfeeders a prime location to confirm breeding.

For more general information on the breeding habits of the Downy Woodpecker, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Downy Woodpecker breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Downy Woodpecker breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Downy Woodpecker phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

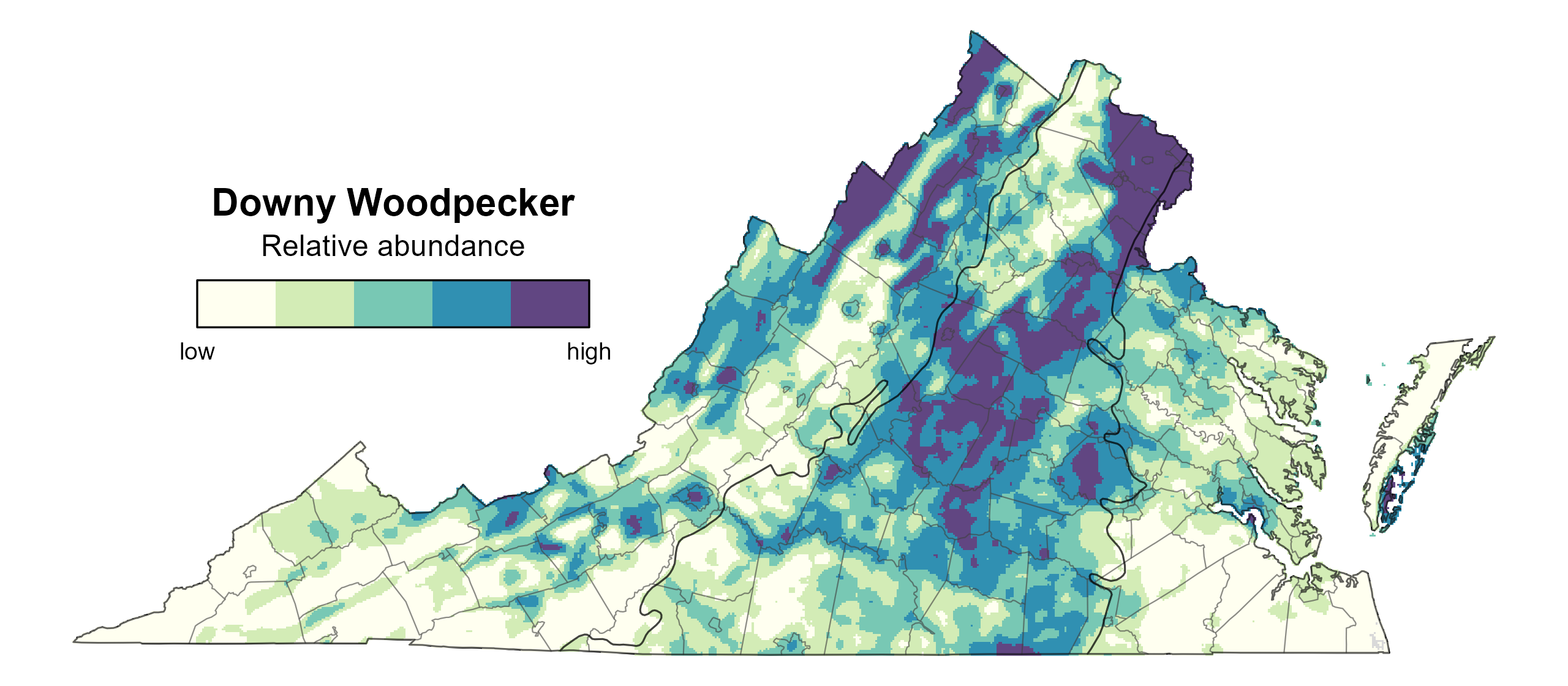

Downy Woodpecker relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the northwestern Mountains and Valleys region, the Northern Virginia area, and the central Piedmont region (Figure 5). It was projected to be lowest in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area, Eastern Shore, and southwestern portion of the Mountains and Valleys region.

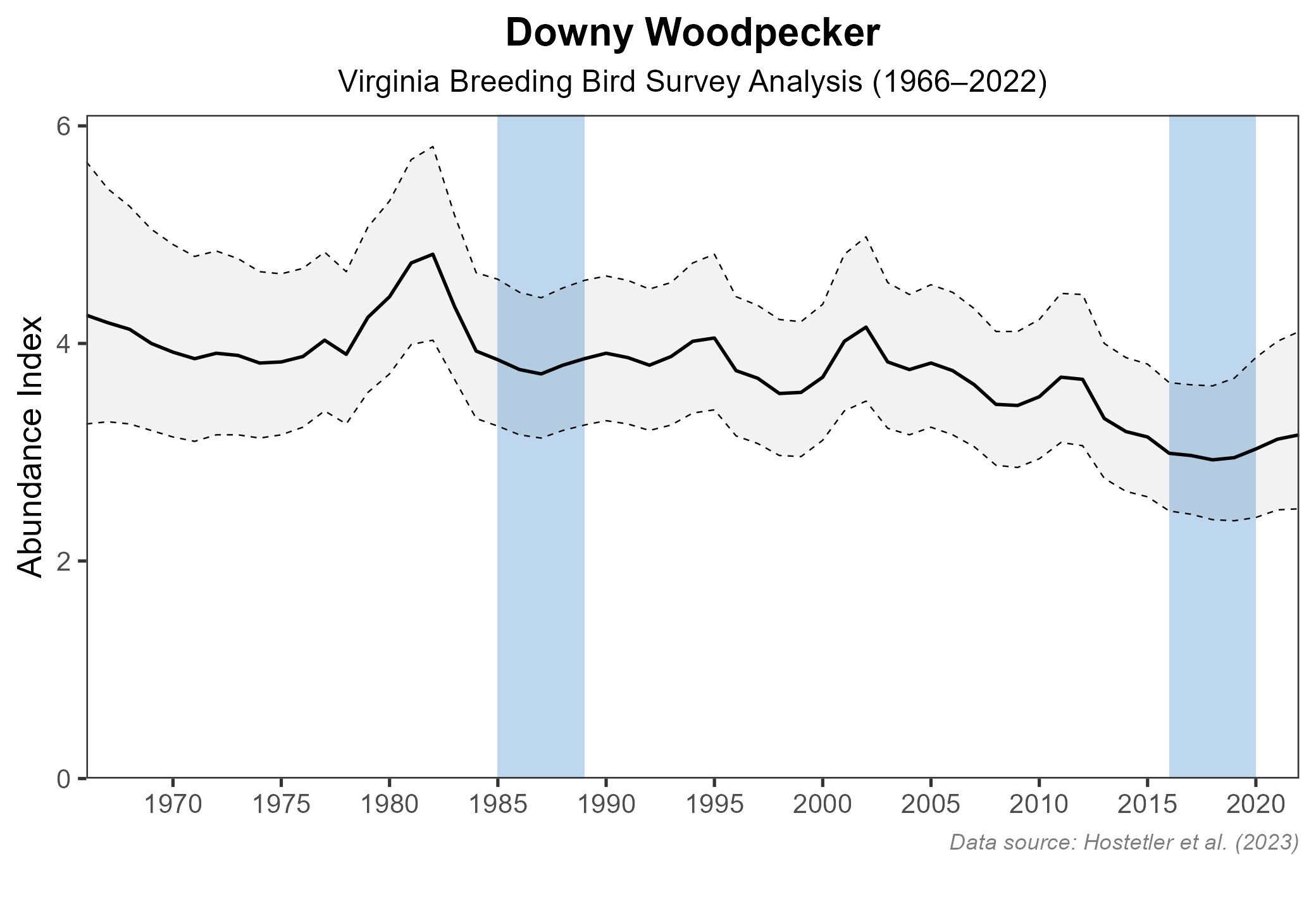

The total estimated Downy Woodpecker population in the state is approximately 1,126,000 individuals (with a range between 613,000 and 2,067,000). For the woodpecker’s population trend in the state, the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) showed a nonsignificant decrease of 0.54% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 6). Between Atlases, BBS trend data showed a significant decrease of 0.76% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Downy Woodpecker relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 6: Downy Woodpecker population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Downy Woodpeckers are widespread and abundant in the Commonwealth, and they are not a species of concern. Their ability to adapt to human-modified habitats, including nesting in wooded fenceposts in cleared agricultural lands, has made them one of the hardiest and most familiar species (Jackson and Ouellet 2020). Like many woodpeckers, this species benefits when landowners leave standing dead trees and branches that they can use for nest sites.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Conner, R. N., and C. S. Adkisson (1977). Principal component analysis of woodpecker nesting habitat. Wilson Bulletin 89:122–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4160877.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Jackson, J. A., and H. R. Ouellet (2020). Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.dowwoo.01.

Prum, R. O., and L. S. (2012). The hairy-downy game: a model of interspecific social dominance mimicry. Journal of Theoretical Biology 313:42–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.07.019.