Introduction

While drab in comparison to other forest dwellers such as the Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea), the Wood Thrush makes up for its subdued plumage with a rich, melodic song that is often compared to a flute’s tone. For many who live in Virginia’s more forested regions, the Wood Thrush’s easily recognized ee-oh-lay signals a welcome beginning to warmer temperatures and woodland hikes. Wood Thrush are most successful in mature tracts of forest and large woodlots that are set within a landscape of contiguous forest, lacking extensive forest fragmentation (Evans et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

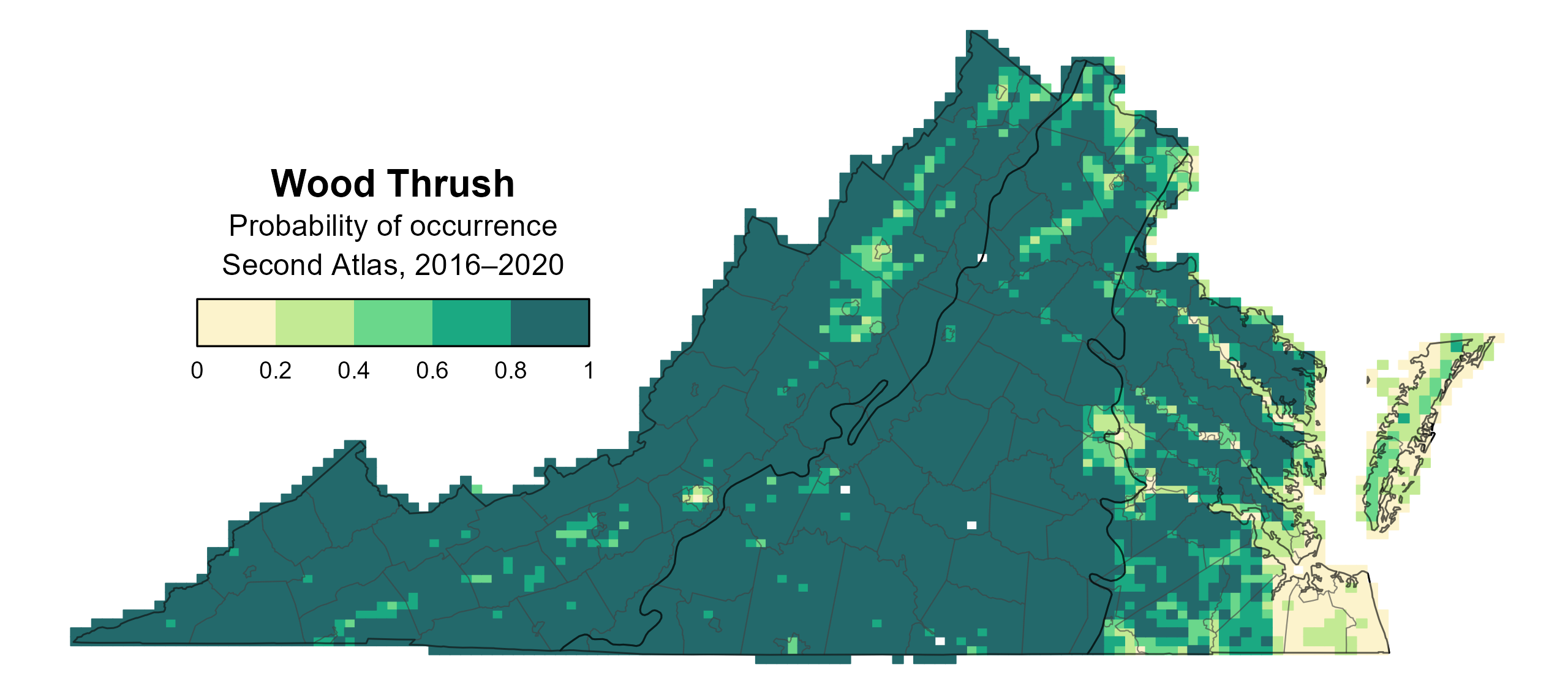

Wood Thrushes are found in all regions of Virginia, although they are most likely to occur in the Mountains and Valleys region, especially in this region’s heavily forested reaches, and in the central and southern Piedmont (Figure 1). They are less likely to occur in the sparsely forested areas of the Coastal Plain and in the state’s highly urbanized areas. Their likelihood of occurrence is slightly negatively associated the number of habitat types in a block. Forest cover is the greatest predictor of whether Wood Thrush will be found in a block, and the species will breed at almost any elevation.

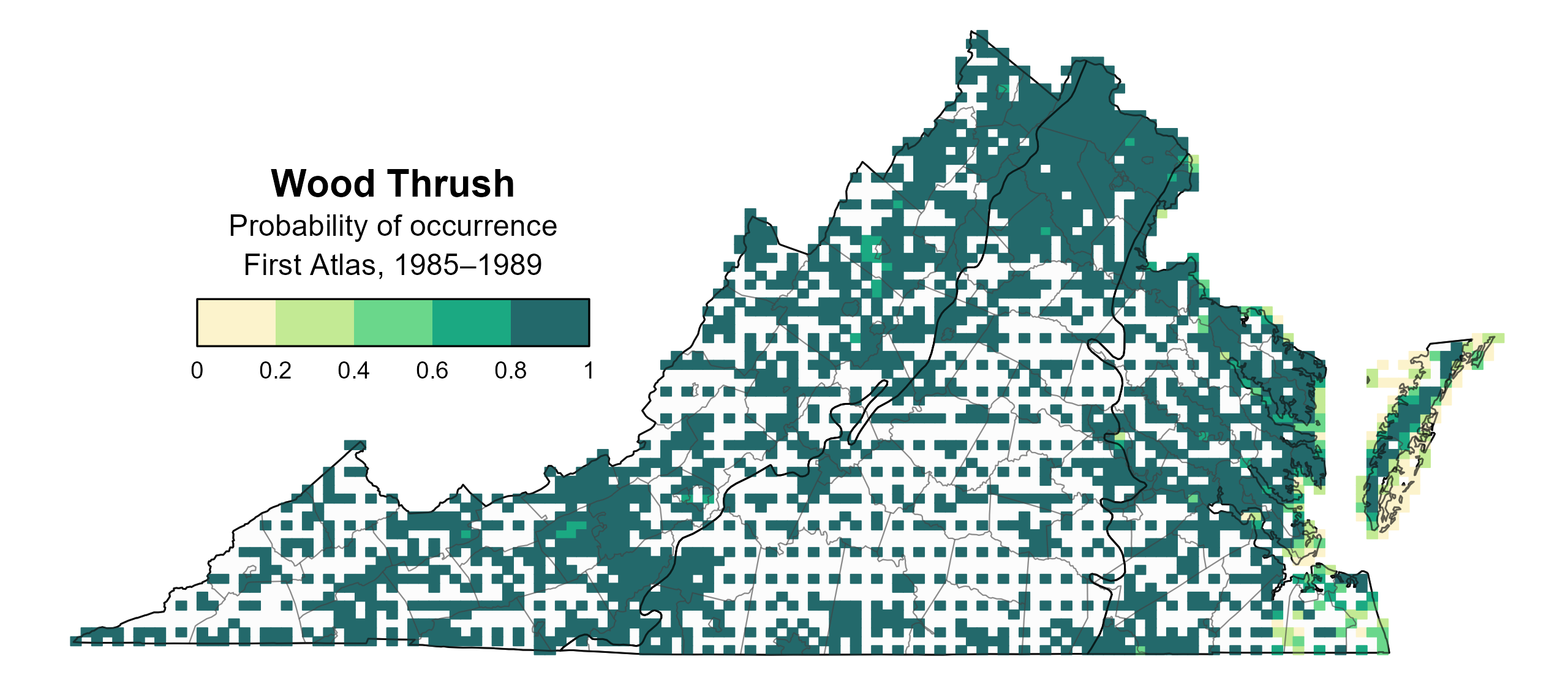

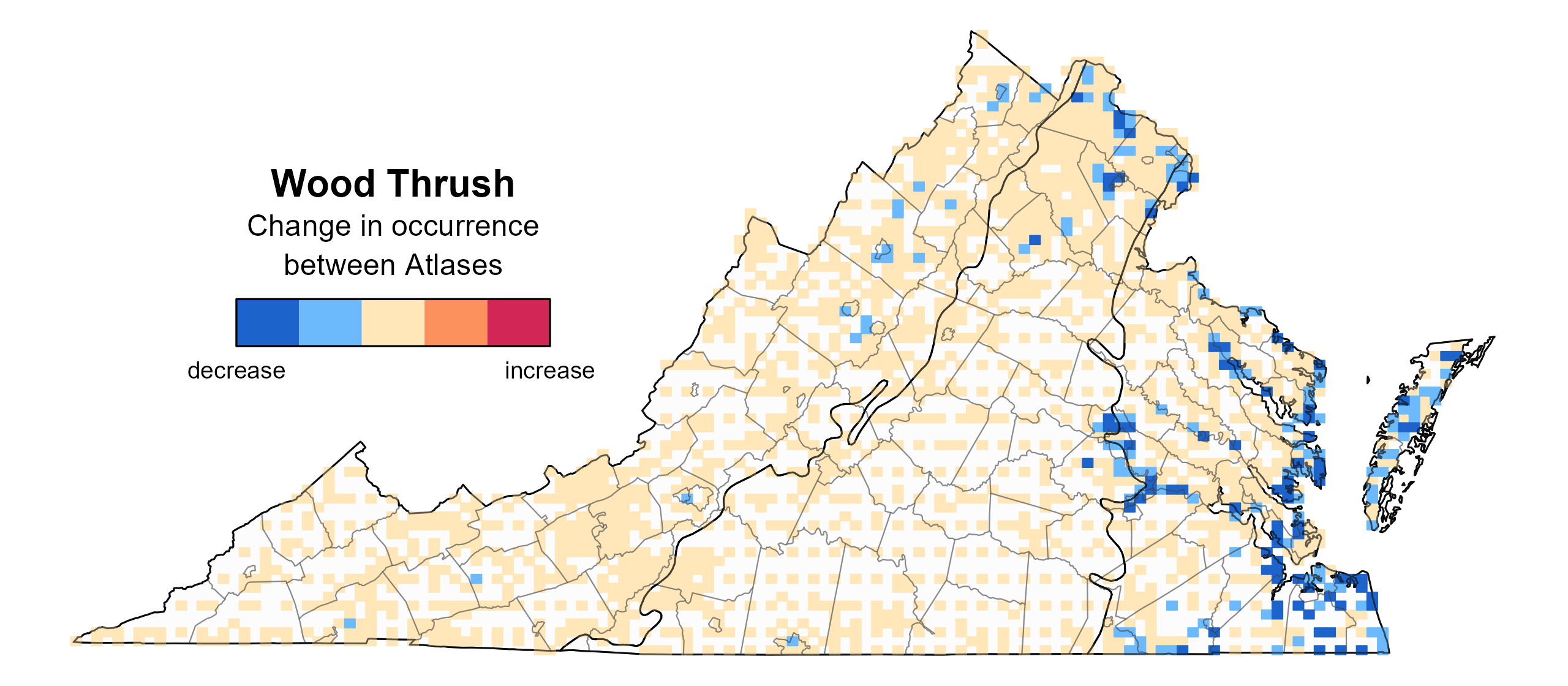

Despite a steadily declining population trend (see Population Status), Wood Thrush predicted occurrence across the state remained mostly constant from the First to Second Atlas (Figures 1 and 2). Some decreases in likelihood of occurrence took place in the northern Piedmont region, in highly urbanized areas near Richmond, along the Eastern Shore, and in marginal habitat of the Coastal Plain (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Wood Thrush breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Wood Thrush breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Wood Thrush change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

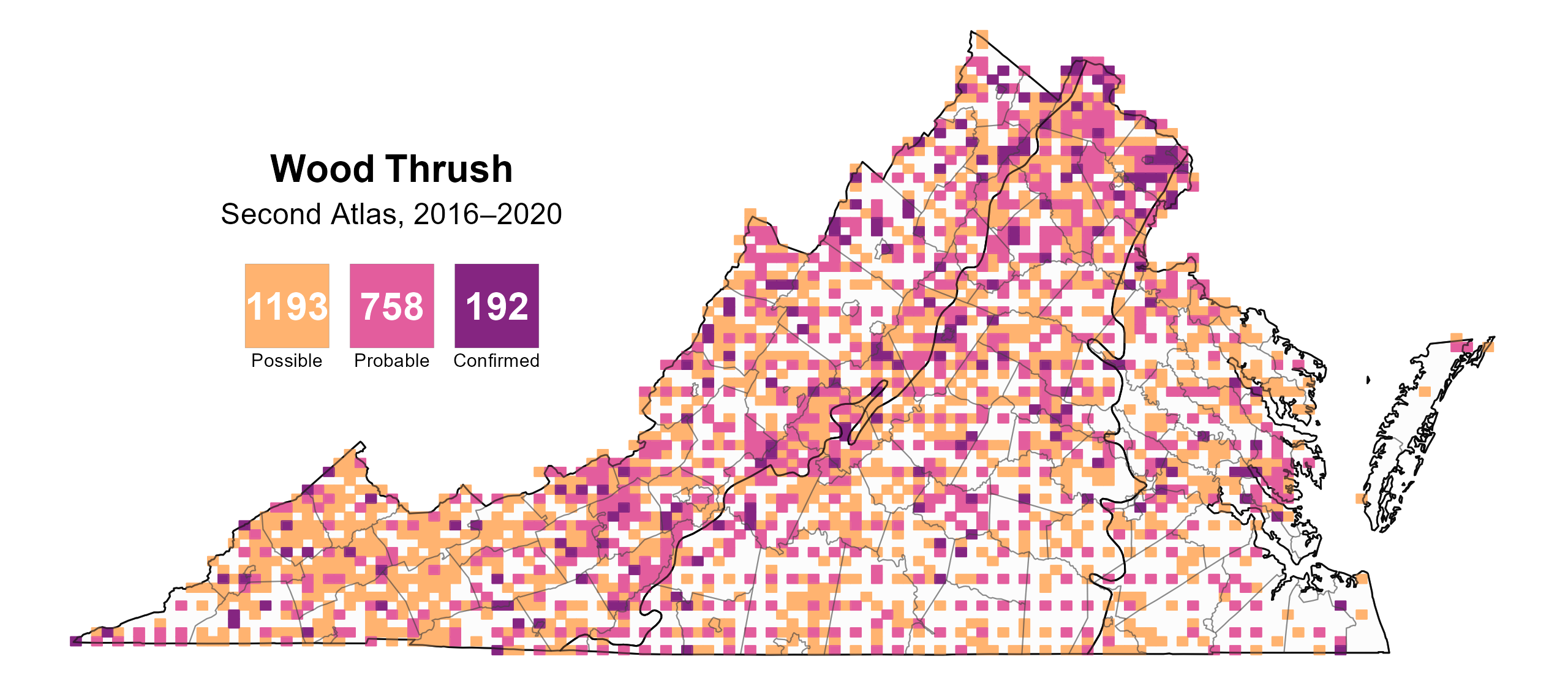

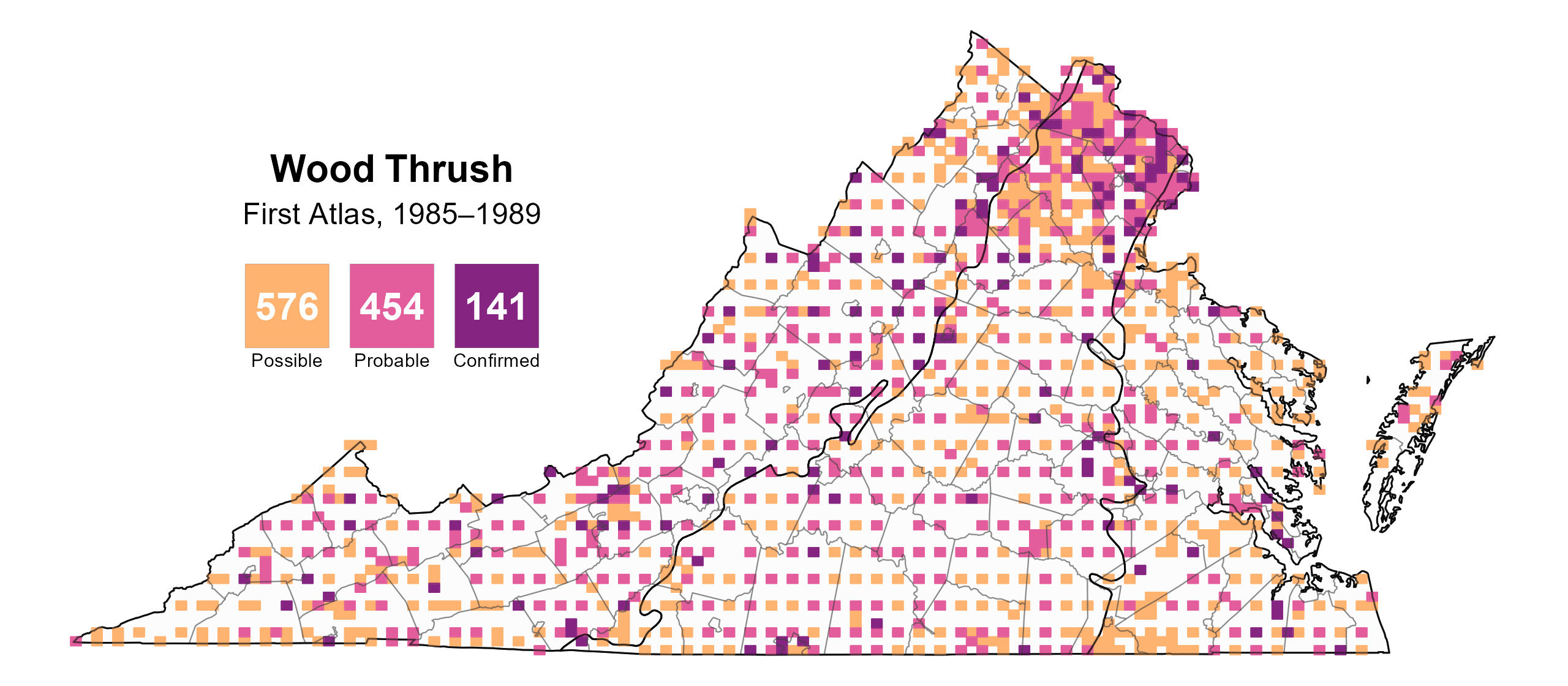

Wood Thrushes were confirmed breeders in 192 blocks and 79 counties and probable breeders in an additional 34 counties (Figure 4). Breeding observations were recorded throughout the state during both Atlas periods (Figures 4 and 5).

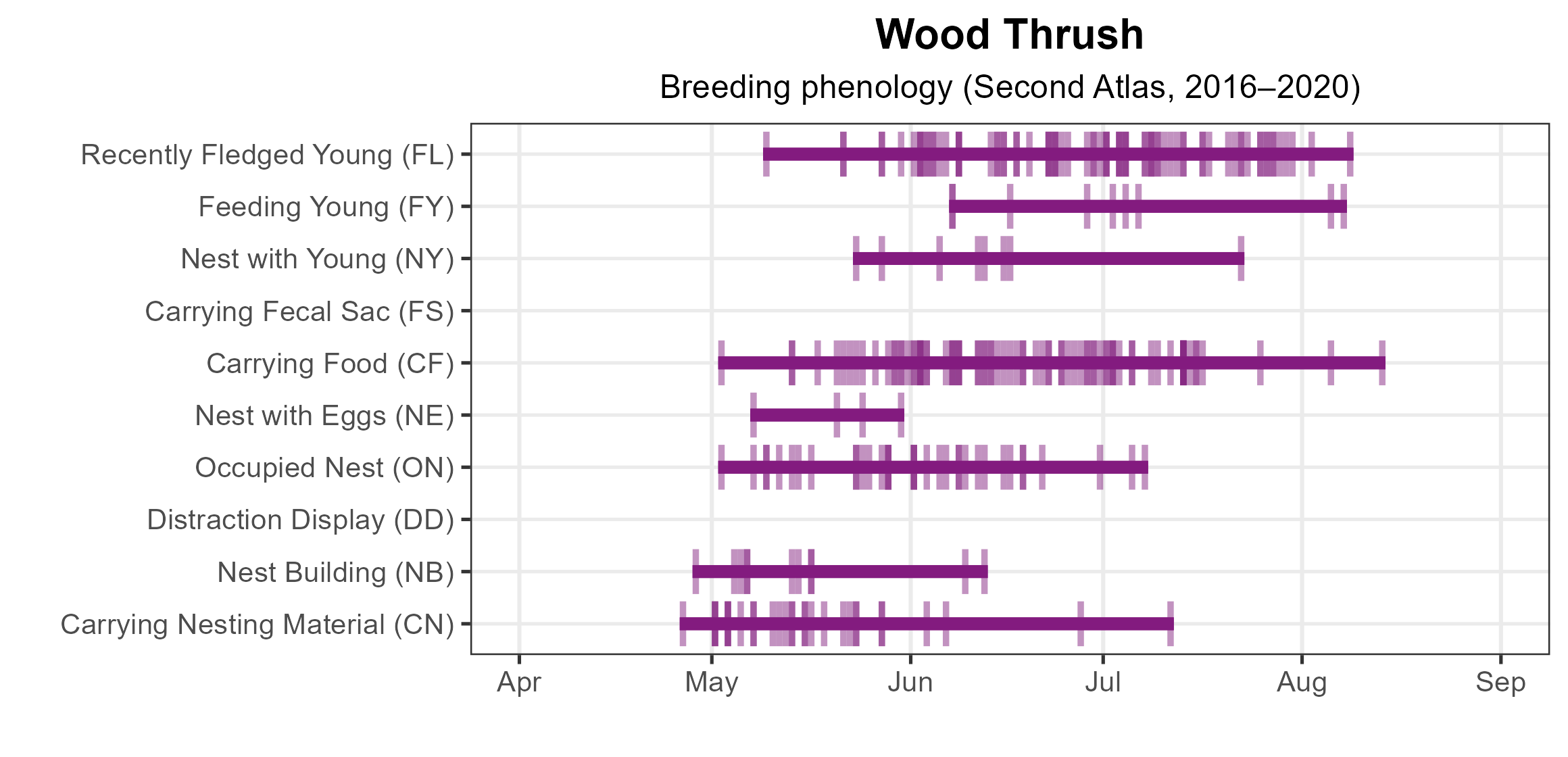

The earliest confirmed breeding behavior was recorded at the end of April, when adults carrying nesting material were observed (Figure 6). Most breeding confirmations were based on observations of adults carrying food (May 2 – August 13), occupied nests (May 2 – July 7), and recently fledged young (May 9 – August 8). Wood Thrushes place their nests in shrubs and saplings in the forest understory. Compared to other forest birds that nest high in the canopy, this species is a relatively conspicuous breeder, with nests typically 10–13 ft (3–4 m) above the ground, making it easy to document breeding evidence (Rosenberg et al. 2003). Atlas volunteers in fact reported Wood Thrush nests at approximately 8 ft (2.4 m) in height in pawpaw (Asimina triloba) and 9 ft (2.7 m) in spicebush (Lindera benzoin).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Wood Thrush breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Wood Thrush breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Wood Thrush phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Wood Thrush relative abundance was estimated to be highest and most consistent in the extensively forested portions of the western Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 7).

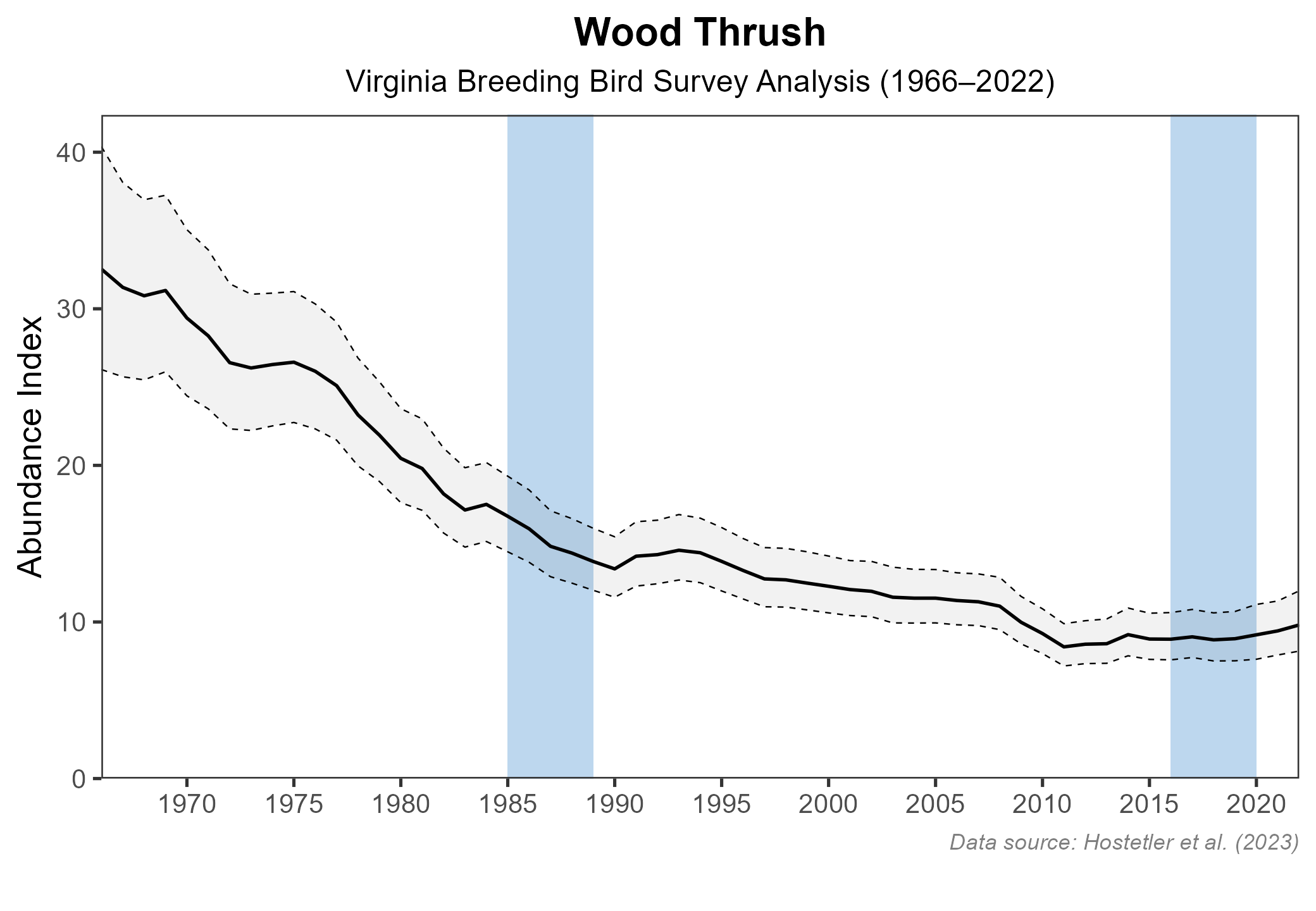

The total estimated Wood Thrush population in Virginia is approximately 424,000 individuals (with a range of 356,000 to 506,000). The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) indicates that this species experienced a significant annual decline of 2.09% in Virginia between 1966 and 2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7). This species’ population also decreased between Atlas periods (1987-2108), although at a lower but still significant annual rate of 1.64%.

Figure 7: Wood Thrush relative abundance based on predicted density.

Figure 8: Wood Thrush population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Despite the severity of its decline in Virginia, the Wood Thrush’s still widespread distribution and robust population in the Commonwealth led to its being classified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need Tier IV (Moderate Conservation Need) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). The species is emblematic of the crucial need for conservation partnerships, as approximately 25% of the global Wood Thrush population breeds in just three states: West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Rushing et al. (2015) used BBS abundance and trend data to group Wood Thrush into “natural populations” across its breeding range. Virginia falls within three such regional populations; each of these deserves a closer look, as the threats and factors responsible for their decline may differ among them.

Recent science suggests that habitat loss on their wintering grounds in Mexico and portions of Central America plays a major decline in range-wide Wood Thrush population declines (Rushing et al. 2016). In 2025, Virginia participated in a range-wide Wood Thrush tracking study coordinated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine where individuals from each the Commonwealth’s three natural populations overwinter. Once results are available, it is hoped that they will shed further light on the role that the species’ wintering grounds play in its conservation.

In addition to habitat loss on the wintering grounds, loss and degradation of breeding habitats appears to be the primary driver of the steepest regional declines in Wood Thrush (Rushing et al. 2016). Wood Thrush populations experience several additional interacting stressors. A history of logging, going back to the turn of the 20th century, has left Virginia with an overabundance of even-aged forest. While Wood Thrush build their nests in mature forests, they move their fledglings to nearby young forest to forage prior to fall migration. A lack of forest-age diversity, therefore, reduces habitat quality and fledgling survival (Evans et al. 2020). One solution is to actively diversify forest age classes through sustainable forestry on both public and private lands.

Many of Virginia’s Wood Thrush continue to breed in relatively small forest patches resulting from fragmentation. As an example, one nest was reported by an Atlas volunteer just outside the front door of a residence in a subdivision in Fairfax County. This tolerance for reduction in forest size has contributed to the species’ resilience in the Commonwealth; however, fragmentation may negatively impact its reproductive success by, among other factors, increasing rates of nest parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) and by compounding the effects of acid rain on prey availability (Evans et al. 2020).

Guidelines for forest management to benefit Wood Thrush have been published and are available for implementation (Rosenberg et al. 2003; Lambert et al. 2017). The Ruffed Grouse Society and Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture are working with partners such as the Virginia Department of Forestry and Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources in the Alleghany Highlands and in southwest Virginia to execute projects that showcase such management on public lands.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Evans, M., E. Gow, R. R. Roth, M. S. Johnson, and T. J. Underwood (2020). Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.woothr.01.

Fynn, I. (2022) Understanding changes in Wood Thrush and Ovenbird populations in Virginia—the role of forest fragmentation and connectivity. Journal of Environmental Protection 13:797–818.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Lambert, J. D., B. Leonardi, G. Winant, C. Harding, and L. Reitsma (2017). Guidelines for managing Wood Thrush and Scarlet Tanager habitat in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions. High Branch Conservation Services, Hartland, VT, USA.

Rosenberg, K.V., R.S. Hames, R.W. Rohrbaugh, Jr., S. Barker Swarthout, J.D. Lowe, and A.A. Dhondt (2003). A land manager’s guide to improving habitat for forest thrushes. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Ithaca, NY, USA. 29 pp.

Rushing C. S., T. B. Ryder, A. Scarpignato, J. Saracco, and P. P. Marra (2015) Using demographic attributes from long-term monitoring data to delineate natural population structure. Journal of Applied Ecology 53:491–500.

Rushing C. S., T. B. Ryder, and P. P. Marra (2016) Quantifying drivers of population dynamics for a migratory bird throughout the annual cycle. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 283:20152846.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.