Introduction

Once considered the same species, the Winter Wren was split into three species in 2010: the Eurasian Wren of the Old World, the Pacific Wren of western North America, and the Winter Wren of the eastern United States and Canada (Hejl et al. 2020). Though much more widespread in the state during the winter months (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), the Winter Wren’s breeding range within Virginia is restricted to areas of high elevation within the Mountains and Valleys region. Like other wrens, the Winter Wren is best known for its singing ability. With its short, stubby tail cocked, the Winter Wren produces a loud cascading song of musical notes that can last up to 10 seconds (Hejl et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

The Winter Wren in Virginia is represented by the Appalachian subspecies (Troglodytes hiemalis pullus), whose distribution extends into northern Georgia, and which is distinct from the nominate subspecies that populates the Northeast and Canada (Hejl et al. 2020; Wilson and Watts 2012). Within the western third of the state, it is most likely to occur in isolated high-elevation forests in Augusta, Bath, Buchanan, Giles, Grayson, Highland, Rockingham, Shenandoah, and Smyth Counties (Figure 1).

In addition to an affinity for higher elevations, Winter Wrens are more likely to be found in blocks with higher proportions of forest edge habitat. Across its broader breeding range, the species is associated with both coniferous and mixed-deciduous forests, often in small openings or forest edges (Hejl et al. 2020). Atlas volunteers documented the species in habitats that included mature hardwood forest with dead standing eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) trees and dense shrub cover as well as along a stream running through a red spruce (Picea rubens) stand.

Due to limited data, Winter Wren distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled. Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on where it occurred during the First Atlas.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Winter Wren breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

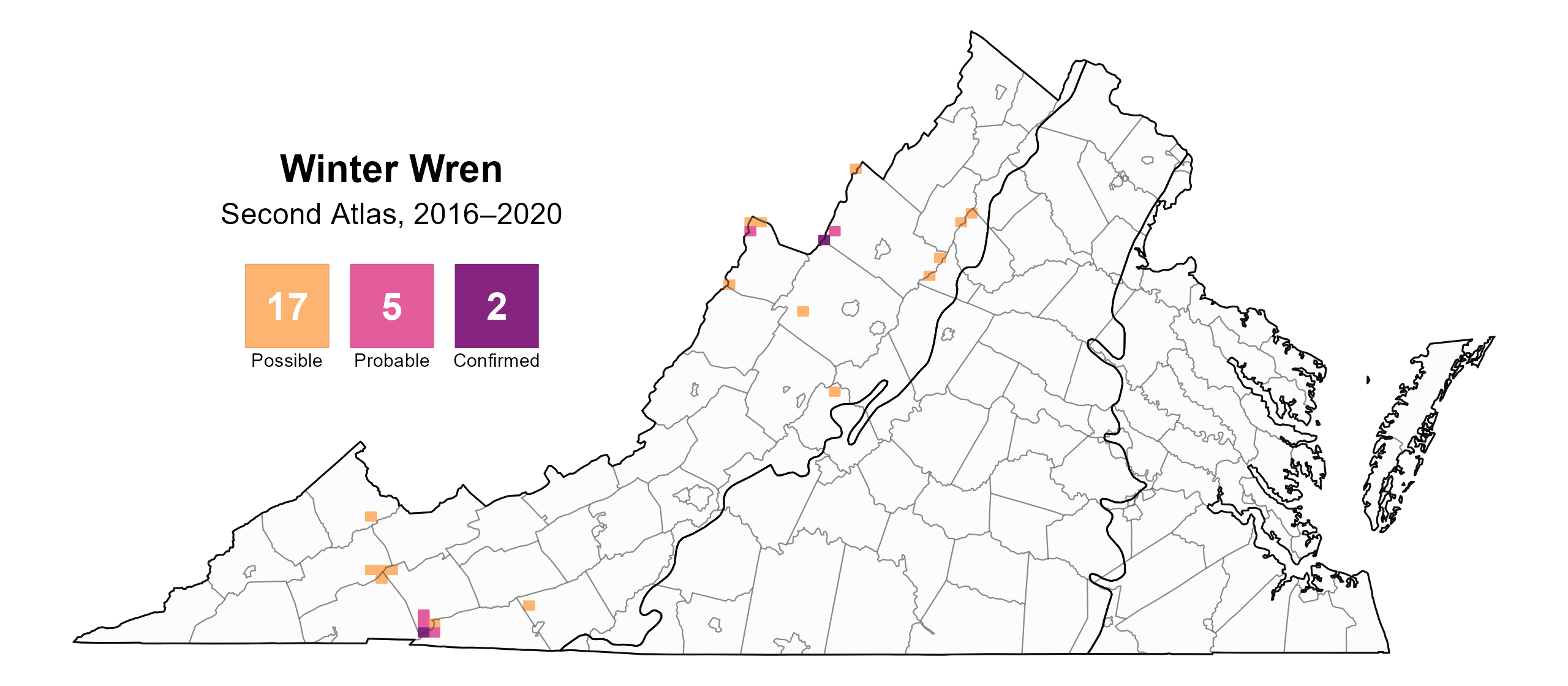

Winter Wrens were confirmed breeders at only two locations: at Reddish Knob in Augusta County and in a mixed spruce and hardwood stand on Whitetop Mountain in Grayson County. They were found to be probable breeders in an additional four counties (Highland, Rockingham, Smyth (including Mount Rogers), and Washington) (Figure 2). Despite greater survey effort during the Second Atlas, Winter Wrens were documented in roughly the same number of blocks in the First Atlas (Figure 3).

There were only two records of confirmed breeding for Winter Wren in the Second Atlas. Recently fledged young were recorded on July 19, and adults carrying food were observed on July 31 (Figure 4).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Winter Wren breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Winter Wren breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Winter Wren phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

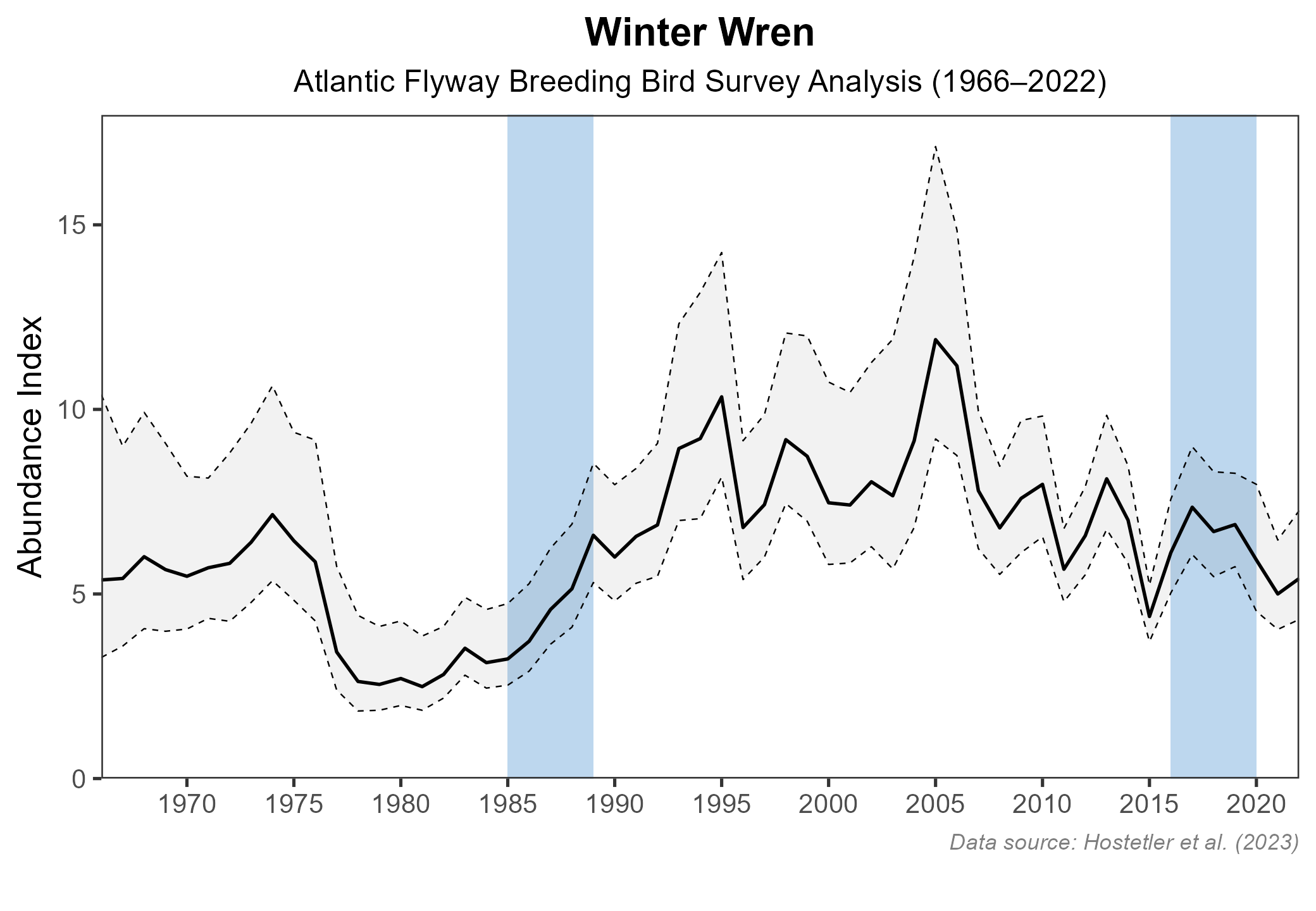

Given that only one individual was detected during Atlas point count surveys, Winter Wren abundance could not be modeled. Similarly, Winter Wrens in Virginia are detected on a low number of routes of the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), preventing estimation of a credible population trend for the state. However, at the Atlantic Flyway scale, the Winter Wren population remained stable in the region, with a nonsignificant 0.02% annual increase between 1966 and 2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between Atlas periods, its population trend showed a slight significant increase of 1.21% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Winter Wren population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The Appalachian Winter Wren is identified as a Tier III (High Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). Although it is not trending negatively, its population size is currently believed to be relatively small, making it vulnerable to extirpation.

In Virginia, breeding Winter Wrens inhabit elevations ranging from 2,930 to 5,350 ft (893 m to 1,631 m) (Lessig 2008), which limits their distribution to isolated high-elevation forests. The Second Atlas can serve as a jumping-off point for a more targeted effort at collecting more comprehensive breeding distribution data. Historical records for Virginia evaluated by Wilson and Watts (2012) reveal several high-elevation sites that were not documented in the Second Atlas, and it is unknown whether the species still occurs there. The effects of forest management on the species in Virginia are unclear, given differences in responses to logging, clearcuts, and forest fragmentation in different parts of the breeding range (Hejl et al. 2020) and the lack of Virginia-specific studies. Within the Commonwealth, Winter Wrens tend to be found in relatively remote locations on protected public lands, where impacts from forestry are likely less prevalent. The potential impact of a changing climate on the high-elevation forests on which the Winter Wren depends is of greater concern (Wilson and Watts 2012), as is the loss of tree species with which the bird may associate. For example, eastern hemlock, a component of the northern hardwood forests used by Winter Wren in Virginia, has declined greatly due to infestations by the hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), and it is unclear whether these losses are impacting Winter Wrens.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hejl, S. J., J. A. Holmes, and D. E. Kroodsma (2020). Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.winwre3.01.

Lessig, H. (2008). Species distribution and richness patterns of bird communities in the high elevation forests of Virginia. Master’s Thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M. D. and B. D. Watts (2012). The Virginia avian heritage project: A report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR 12-04. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 48 pp.