Introduction

The Willet is one of the more noticeable shorebirds of Virginia’s coastal habitats. Despite its light gray plumage, its loud pill-will-willet call, and white wing stripe make it easily noticed in flight, hovering in courtship display. It is a common breeder on the barrier islands and in the salt marshes of the Coastal Plain, and it occasionally nests in grain fields within a mile of salt marsh on the Eastern Shore (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Virginia’s breeding population belongs to the Eastern Willet (Tringa semipalmata semipalmata), which nests along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts from New Brunswick, Canada, to Tamaulipas, Mexico. While Western Willets (T. s. inornata) overwinter in Virginia, only the Eastern subspecies breeds here. Eastern Willets migrate to the Caribbean and South America for winter. Banded Willets from Virginia have been re-encountered in the Lesser Antilles and on the northern coast of Brazil (Smith et al. 2022).

Their abundance and visibility made them a popular game bird in the past. Excessive spring hunting and egg collection reduced them to scarcity by the early 1900s (Bailey 1913; Kuerzi 1929). Today, they are again a common breeder on Virginia’s outer Coastal Plain region.

Breeding Distribution

Willets are found on the seaside and bayside of the Eastern Shore. On the Western Shore, they are most likely to occur at the mouth of the York River and Mobjack Bay, where saltmarsh habitat is extensive (Figure 1). They are also most likely to occur in blocks with a high proportion of salt and brackish marshland and a low proportion of forest. Additionally, the model predicts a moderate to high likelihood that Willets are found in a few blocks in freshwater areas of the upper reaches of the Potomac, Rappahannock, and James Rivers as well as in several blocks in Back Bay and Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). Although these blocks were selected by the model as a function of environmental factors that are important for the species, Willets are known not to nest there.

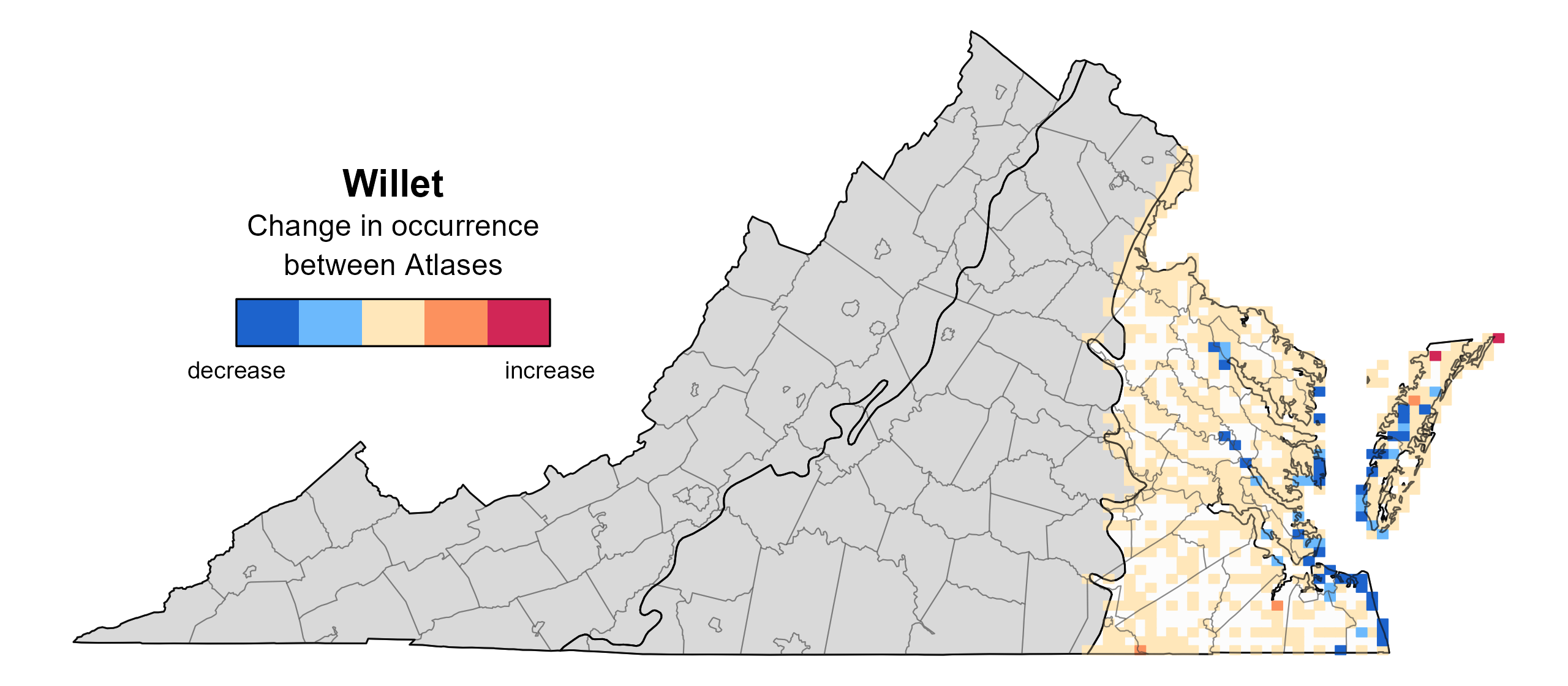

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the Willet’s probability of occurrence declined in some areas of the Eastern Shore and the Western Shore. However, the model also highlights a decline between Atlases in the likelihood of Willet being found in the southern tier of the Tidewater area (including Back Bay, North Landing River, and Great Dismal Swamp NWR). Given the low likelihood that Willets nest in these freshwater areas, this decline should be disregarded.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Willet breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Willet breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the range of the species' core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Willet change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on habitat and environmental factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the range of the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

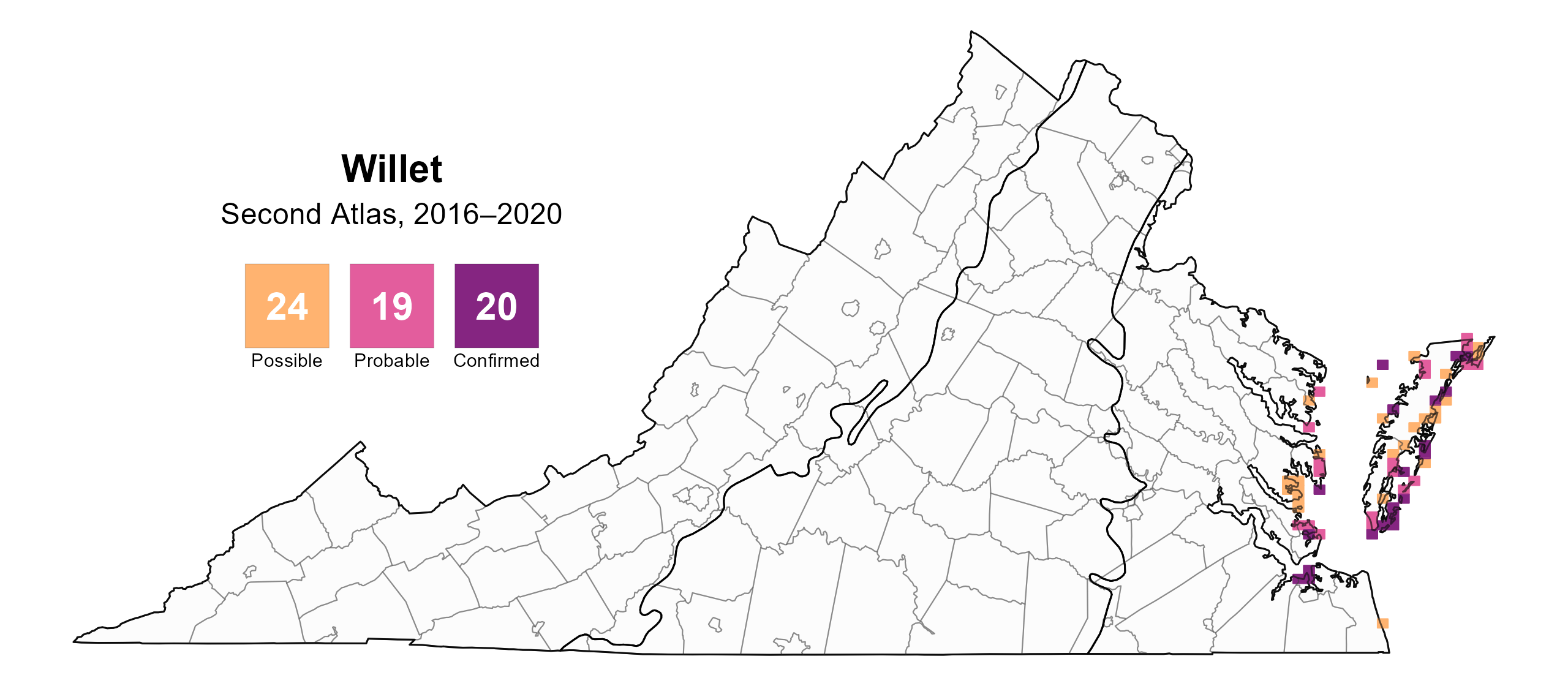

Willets were confirmed breeders in 20 blocks in five counties (Figure 2). On the Eastern Shore, confirmations were continuous along most of the Atlantic coastline, from the Chincoteague Causeway (Accomack) south to Fisherman Island (Northampton). Bayside, they were confirmed at Great Fox Island and in one block near Pungoteague.

On the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, breeding was more scattered. Confirmed breeding sites included Bethel Beach and New Point Comfort Natural Area Preserves in Mathews County, Messick Point and TJ Rollins Natural Area in Poquoson, and three blocks at the Craney Island Disposal Area in Portsmouth.

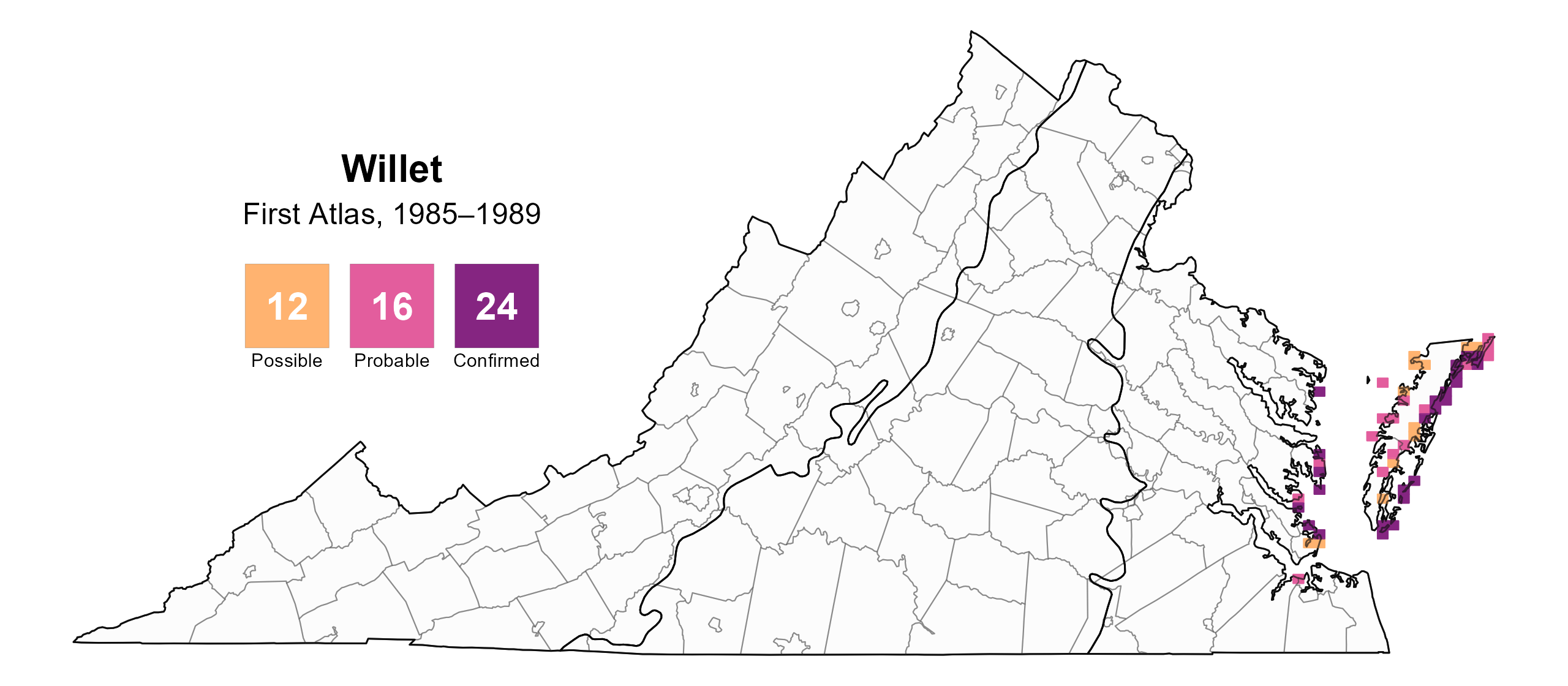

The distribution of breeding confirmations was largely the same as that during the First Atlas (Figure 5).

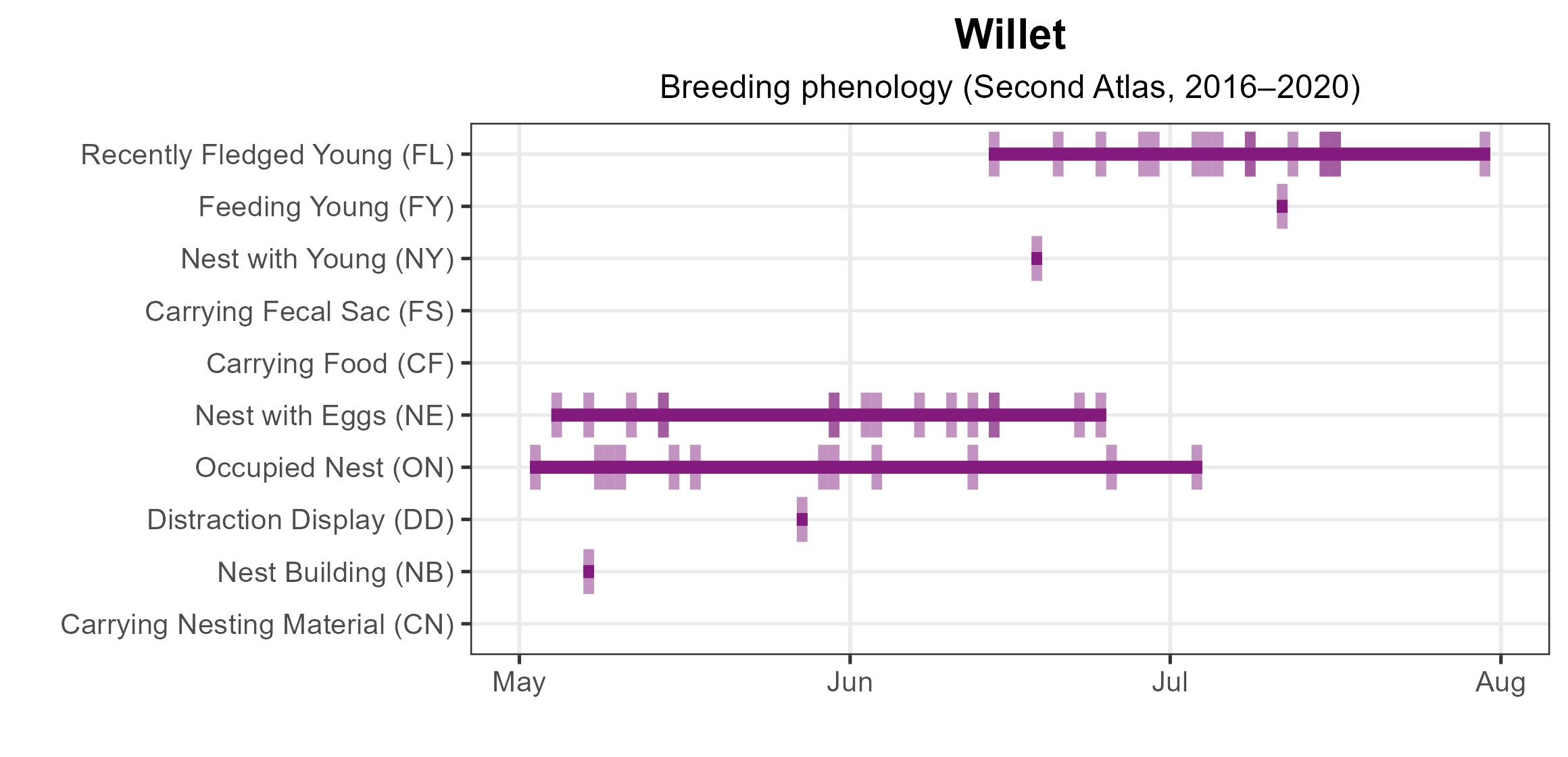

Birds were observed on nests from May 2 through July 3, with dependent young from June 14 through July 30 (Figure 6).

Figure 4: Willet breeding observations from the Second Atlas. The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Willet breeding observations from the First Atlas. The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Willet phenology: confirmed breeding codes from the Second Atlas. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Limited detections during the point count surveys prevented the development of an abundance model for the Willet. Comprehensive population trend estimates are not available from the North American Breeding Bird Survey for the Willet. In point count surveys of Atlantic salt marshes, Correll et al. (2017) found no trend for Willets between 1998 and 2012.

Conservation

Willets are broadly distributed across Virginia’s barrier islands and populations appear robust, despite a lack of reliable trend data. Nonetheless, the species faces ongoing threats from sea-level rise, with high spring tides occasionally flooding nests. Identified conservation actions include predator and human disturbance management and the identification of future marsh sites as current ones are lost to sea level rise, erosion, and subsidence. Willets, and many other migratory shorebirds, also face hunting pressure on their migration and wintering grounds. In 2025, a transmitter-tagged Eastern Willet from Virginia was shot in Guadeloupe (Watts 2025). International collaboration is making progress on conservation efforts for these species throughout the Americas.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated, Lynchburg, VA, USA.

Correll, M. D., W. A. Wiest, T. P. Hodgman, W. G. Shriver, C. S. Elphick, B. J. McGill, K. M. O’Brien, and B. J. Olsen (2017). Predictors of specialist avifaunal decline in coastal marshes. Conservation Biology 31:172–182.

Howe, M. A. (1982). Social organization in a nesting population of Eastern Willets (Catoptrophorus Semipalmatus). The Auk 99:88–102.

Kuerzi, J. F. (1929). Notes on the birds of Cobb’s Island, Virginia. The Auk 46:14–20.

Lowther, P. E., H. D. Douglas, and C. L. Gratto-Trevor (2020). Willet (Tringa semipalmata), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.willet1.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Smith, M. A., J. Mahoney, E. J. Knight, L. Taylor, N. E. Seavy, O. H. Bailey, M. Carbone, W. DeLuca, N. S. Gonzalez, M. F. Jimenz, G. M. W. O’Bryan, et al. (2022). Bird migration explorer. National Audubon Society.

Watts, B. (2025). Deja vu all over again: Tracked eastern willet shot on Guadeloupe. The Center for Conservation Biology, Williamsburg, VA, USA.