Introduction

Swainson’s Warbler pairs an understated appearance with a powerful, resonant song. Its secretive nature and preference for impenetrable vegetation make it challenging to spot, even when actively singing. The bird’s elusive habits are further complicated by its use of markedly different habitats within Virginia.

In the Coastal Plain, Virginia hosts the northernmost coastal population of Swainson’s Warblers in the Great Dismal Swamp. Much of what we know of the species’ basic life history is derived from research on this coastal population (Meanley 1971, 1982). The Appalachian population occupies two distinct habitat types: one dominated by rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.), mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), and American holly (Ilex opaca) and the other consisting of tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera)-oak-maple cove hardwoods with an understory of spicebush (Lindera benzoin) and greenbriar (Smilax spp.) (Anich et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

The Swainson’s Warbler is found in the Coastal Plain region as a locally common breeder in the Great Dismal Swamp, and these warblers represent the northernmost known extension of the coastal population’s range at the time of the Second Atlas. The Mountains and Valleys region no longer represents the northernmost portion of that population’s range as the species is expanding northward in the Appalachian region into West Virginia and Pennsylvania. The species is uncommon and localized in the Mountains and Valleys region.

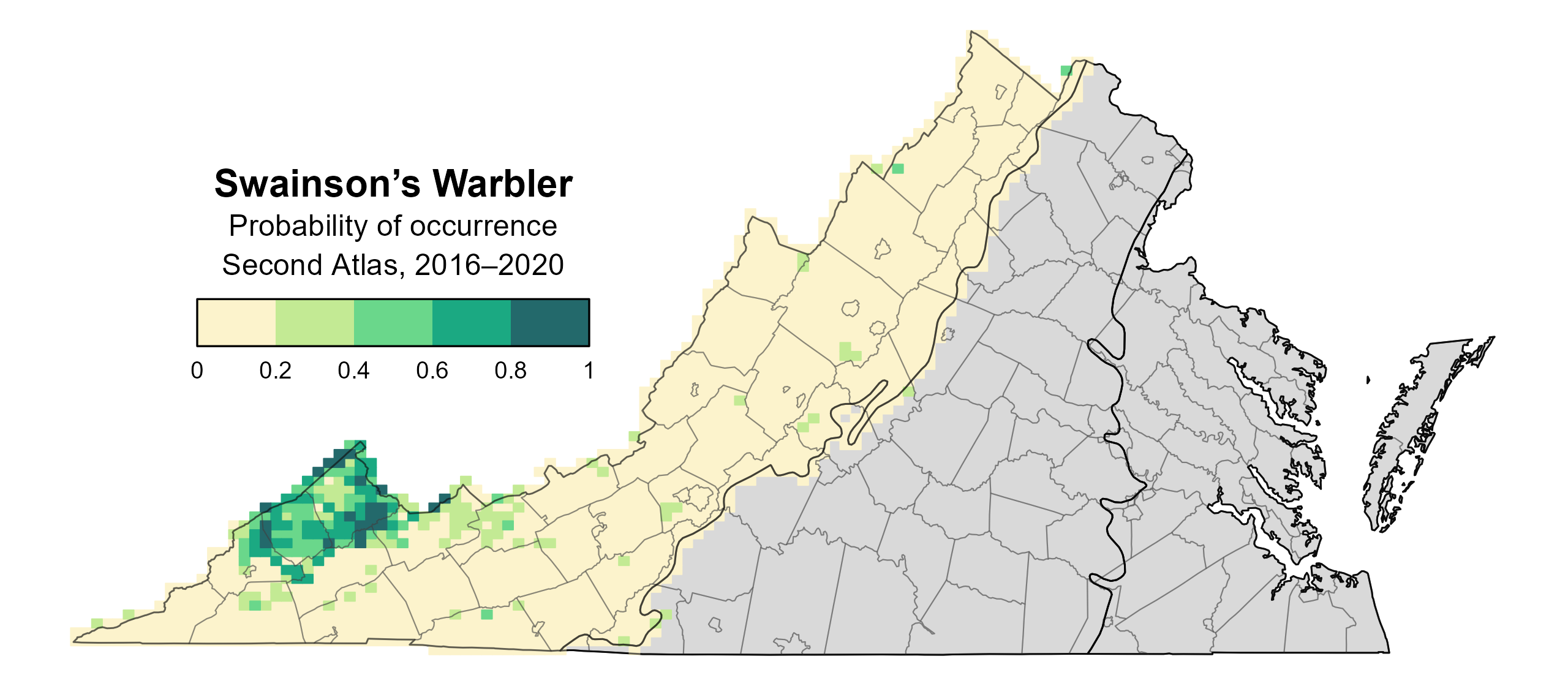

Because of its diverging habitat requirements, its distribution could not be modeled statewide, only in the Mountains and Valleys region, where it is most likely to occur in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties (Figure 1). In this region, the likelihood of finding Swainson’s Warbler’s is highest in blocks with high forest cover, substantial forest edge habitat, and a high abundance of understory evergreen shrubs such as rhododendron and mountain laurel. Research in the core breeding range has shown that typical forest habitat factors, such as canopy height and basal area, are less critical than suitable understory structure, perhaps explaining the species’ use of such varied habitats: a dense thicket is more important than any other habitat feature (Anich et al. 2020).

For breeding records outside of the modeled region and those during the First Atlas (too few breeding observations to model), see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Swainson’s Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

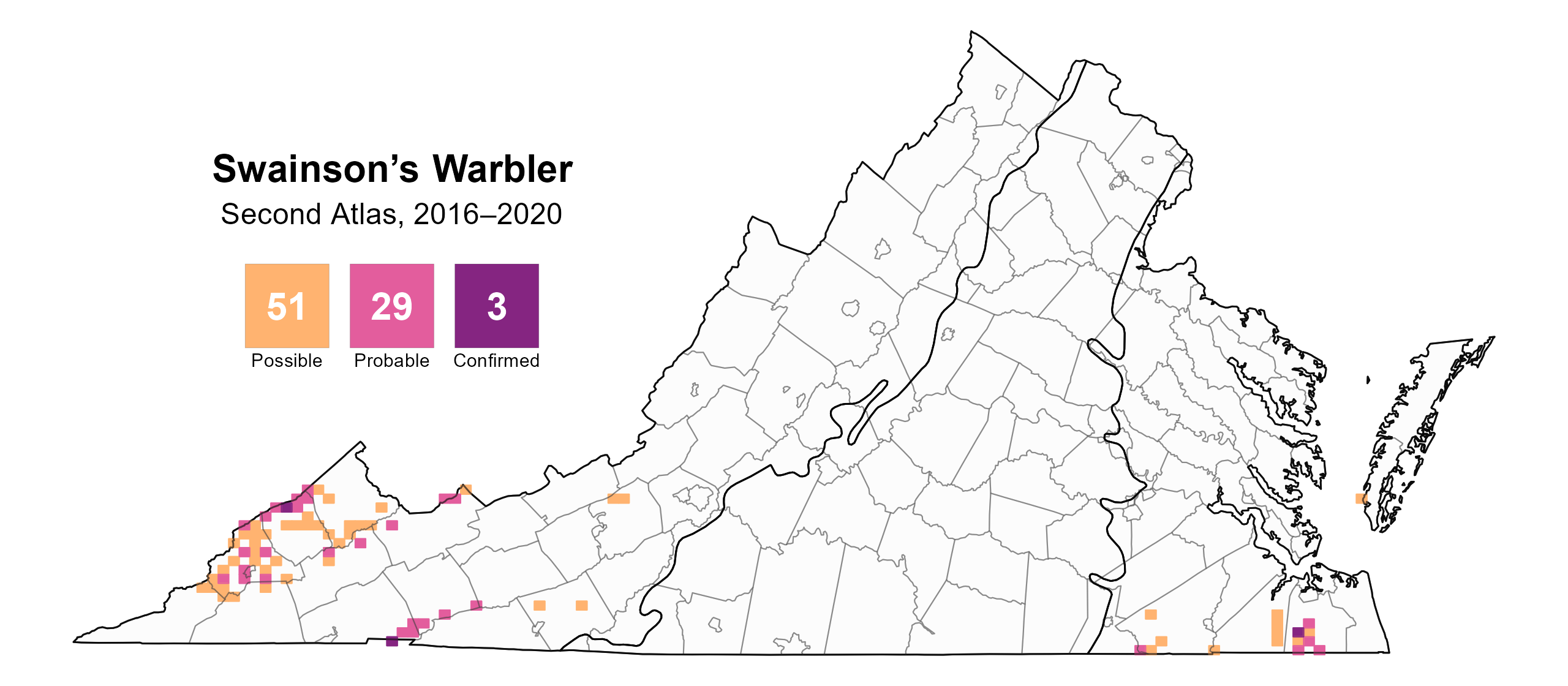

Swainson’s Warblers were confirmed breeders in three blocks the Coastal Plain and Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 2). In the Coastal Plain, confirmed breeders occurred only within the Great Dismal Swamp in the city of Chesapeake, with probable breeding evidence recorded in Greensville County. In the Mountains and Valleys, confirmed breeders were recorded at sites along Blowing Rock Road in Jefferson National Forest in Dickenson County and along Beaverdam Creek in Jefferson National Forest in Washington County. Additional probable and possible records follow accessible roads and waterways in the region.

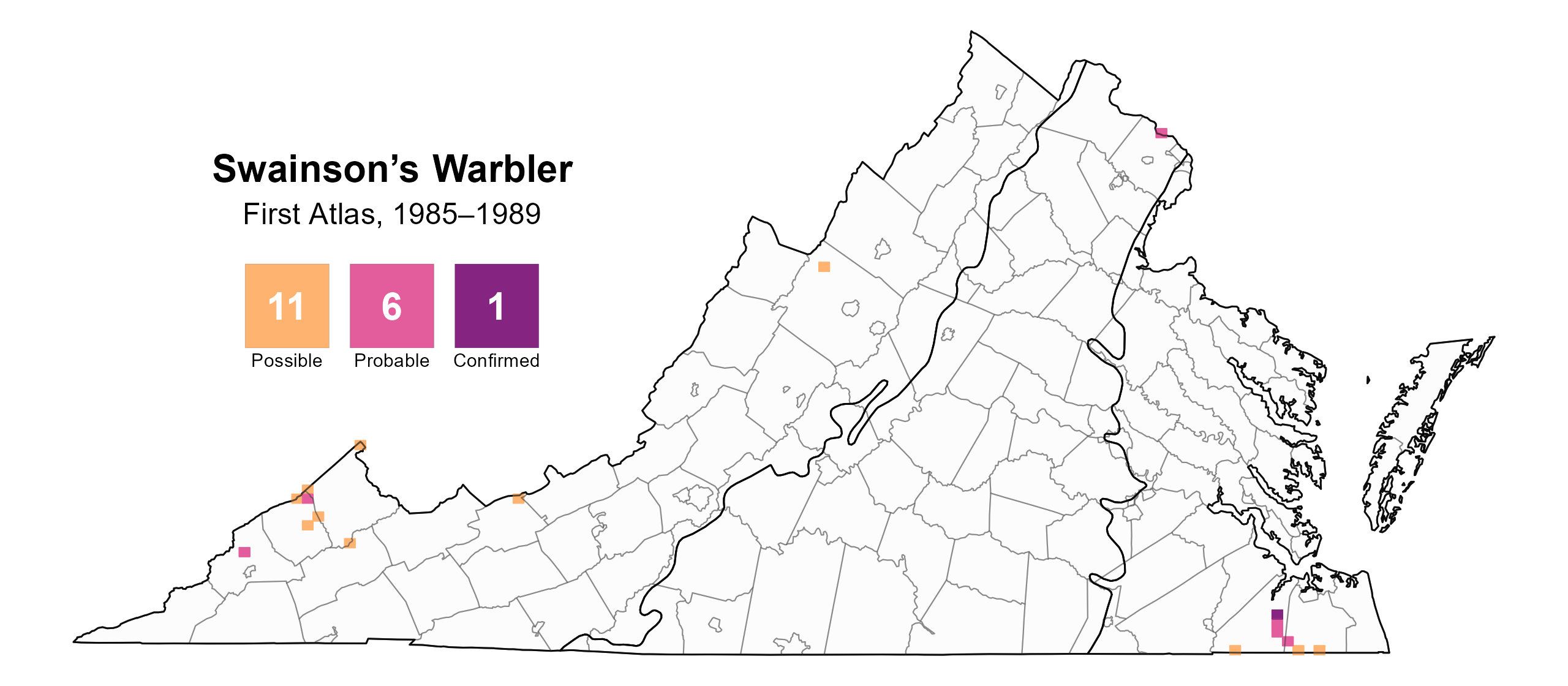

The pattern of recorded breeding evidence closely matches that of the First Atlas, though more intensive surveying during the Second Atlas yielded a greater number of sightings. In the First Atlas, Swainson’s Warbler was confirmed breeding in only one block (Figure 3). Continued surveying of suitable habitats could reveal additional breeding sites, especially in intact bottomland forests in the Piedmont, where small populations may persist undetected.

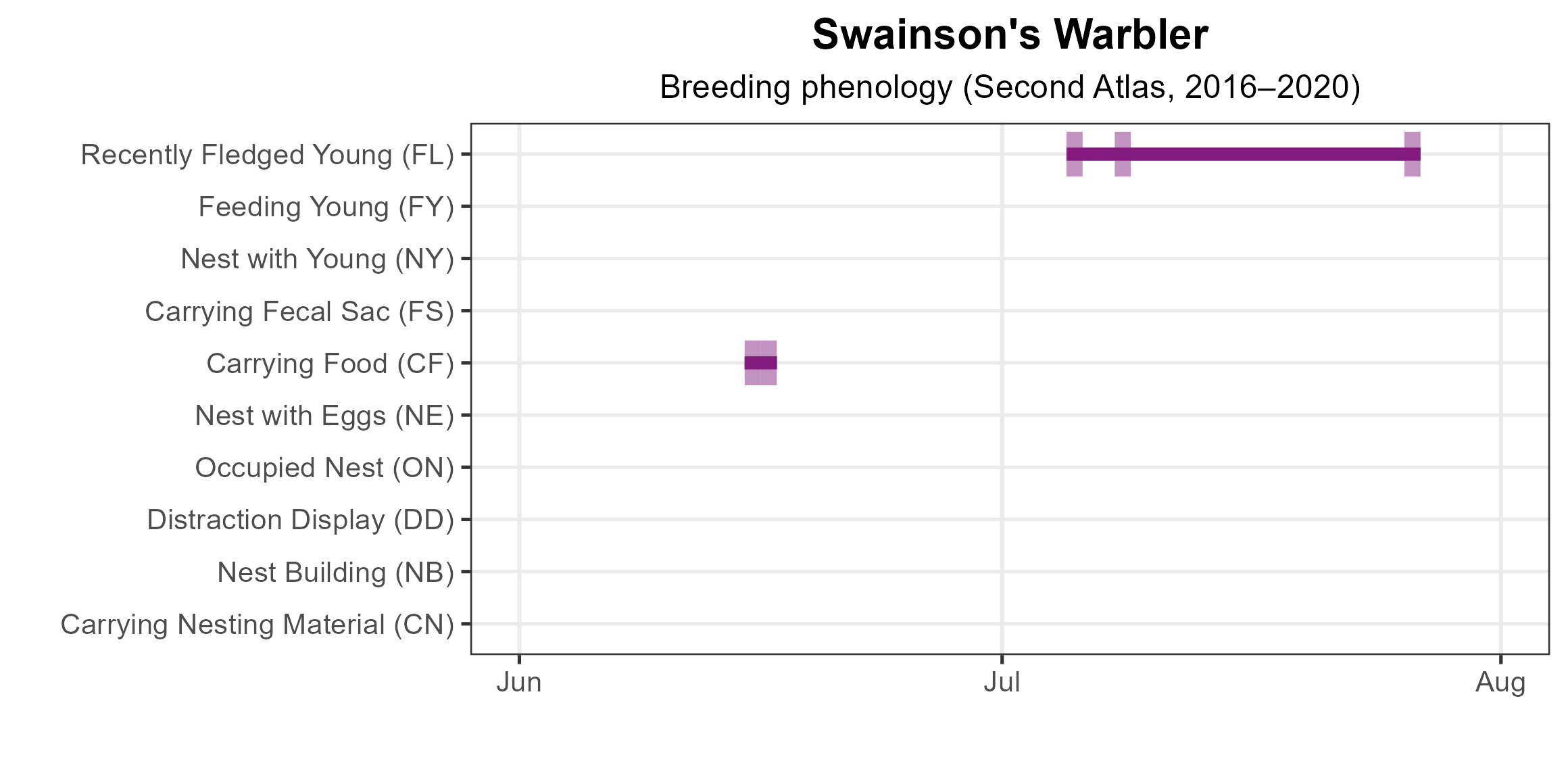

The cryptic behavior of Swainson’s Warblers makes nesting difficult to confirm. Birds are easy to hear but hard to track. Consequently, their phenology is hard to determine. Three confirmations came from fledglings seen from July 5 through July 26 and adults carrying food on June 15 and 16 (Figure 4). No nests were observed during the Second Atlas. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Swainson’s Warbler, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Swainson’s Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Swainson’s Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Swainson’s Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

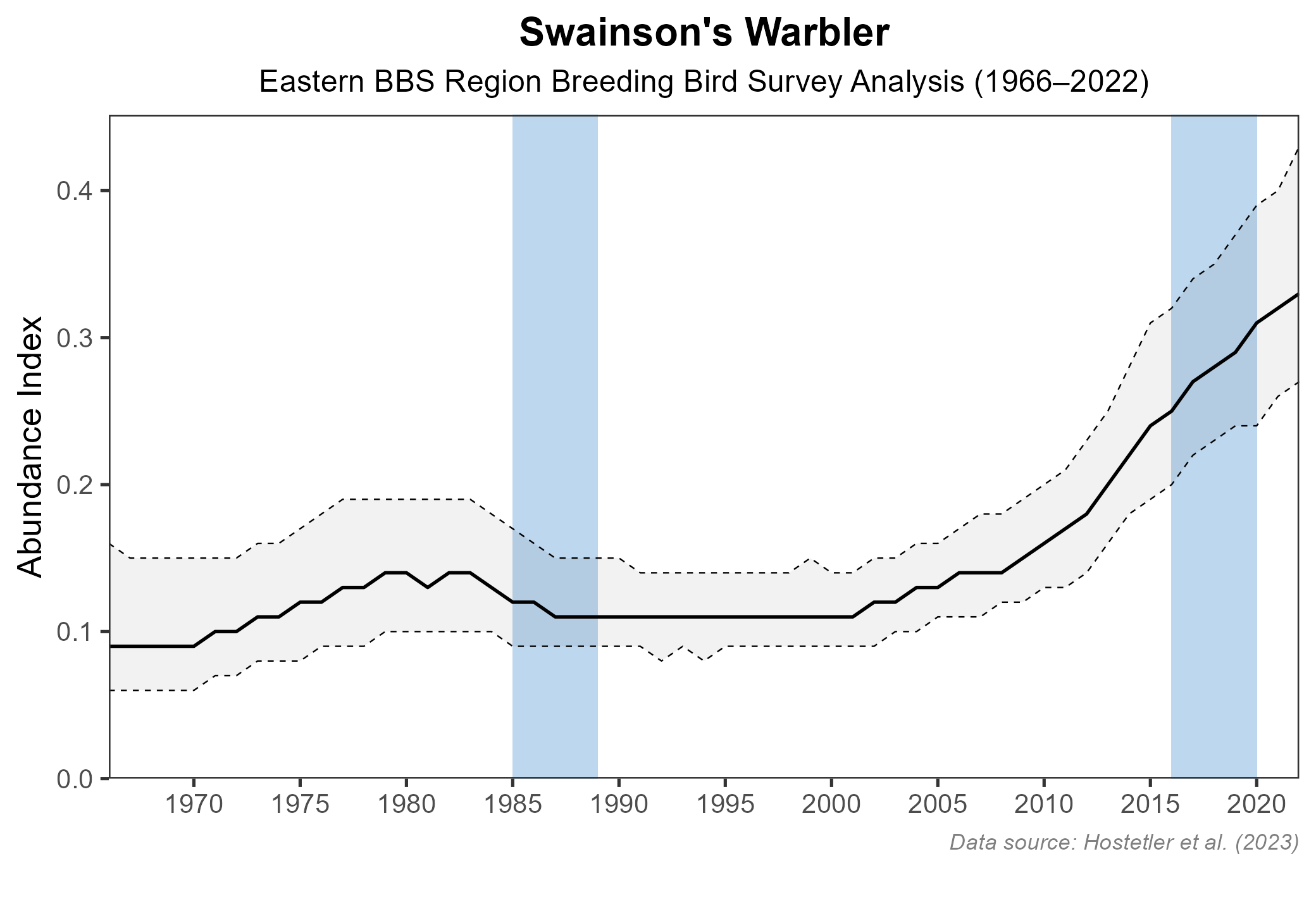

Insufficient detections during Atlas point count surveys prevented the development of an abundance model for the Swainson’s Warbler. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not cover the species well in Virginia, but the population trend for the Eastern BBS region showed a significant increase of 2.31% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between Atlas periods (1987-2018), the trend for the Eastern BBS region showed a similar significant increase of 2.94% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 5: Swainson’s Warbler population trend for the Eastern region as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan classifies Swainson’s Warbler as an Assessment Priority Species because data gaps prevented it from being evaluated as a potential Species of Greatest Conservation Need (VDWR 2025). Specifically, there is uncertainty over how the species is faring in Virginia, despite the positive population trend for the Eastern BBS region. The BBS may not be well-suited to monitoring this species as its habitats are often not accessible from the roadside and as it is better detected using playback. Targeted monitoring is therefore needed to better understand the population trends of Swainson’s Warbler in the two distinct geographies that it occupies in Virginia (VDWR 2025).

Threats to Swainson’s Warbler in Virginia include development in the forested areas of the Cumberland Mountains and the loss of understory structure in forests due to aging, deer overbrowsing, and lack of forest management. The species’ rarity and secretive behavior also make it vulnerable to disturbance from birders attempting to observe it. Excessive use of playback recordings can habituate birds, disrupt breeding behavior, and has been implicated in the disappearance of Swainson’s Warbler from the Pocomoke Swamp in Maryland (Heckscher and McCann 2006; Anich et al. 2020). To minimize disturbance, the use of playback for recreational purposes should be discouraged.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Anich, N. M., T. J. Benson, J. D. Brown, C. Roa, J. C. Bednarz, R. E. Brown, and J. G. Dickson (2020). Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.swawar.01.

Heckscher, C. M., and J. M. McCann (2006). Status of Swainson’s Warbler on the Delmarva Peninsula. Northeastern Naturalist 13:521–530.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Meanley, B. (1971). Natural history of the Swainson’s Warbler. North American Fauna, Number 69. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., USA.

Meanley, B. (1982). Swainson’s Warbler and the Cowbird in the Dismal Swamp. The Raven 53:48–49.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.