Introduction

As the smallest heron in the Americas, the Least Bittern keeps its presence concealed in dense marshes, and its cooing call is easily mistaken for a frog. Least Bitterns prefer brackish and freshwater marshes, particularly those with big cordgrass (Spartina cynosuroides) and other dense wetland vegetation (Wilson et al. 2007). Atlas volunteers observed them in stands of cattail (Typha spp.), native phragmites (Phragmites australis americanus), and pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata). In suitable habitats, they can be abundant, with nesting densities of up to 15 nests per hectare (Poole et al. 2020), and in Virginia, records exist of up to 50 individuals encountered in a day within the impoundments of Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) (Bryan Watts, unpublished data).

Least Bitterns are migratory, breeding in Virginia with very few winter records (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; eBird 2025). Their secretive nature makes them hard to detect; thus, they are likely to occur in more locations than are represented here. Despite this, reports of Least Bittern by birders have dwindled, suggesting they may be experiencing declines. More information on this species is needed.

Breeding Distribution

Because the species is rare, its distribution could not be modeled. For information on where Least Bitterns occur in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Least Bitterns were confirmed breeders in only six blocks and six counties (Figure 1). Most of these breeding locations consisted of marshes along the James, Potomac, Rappahannock, and York Rivers and their tributaries. During dedicated marsh bird surveys along the Delmarva Peninsula in 2022 and 2023, Least Bitterns were detected in all large marshes north of Onancock on the bayside and near Wallops Island on the seaside (Accomack County). Juvenile birds were observed in at least four marshes on the bayside (Chance Hines, unpublished data).

In the Coastal Plain region, breeding was confirmed at Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve (Fairfax County), Neabsco Creek Inlet (Prince William County), Dutch Gap Conservation Area (Chesterfield County), Craney Island Disposal Area (Portsmouth County), and Pleasure House Point Natural Area (Virginia Beach). Breeding was probable at Mason Neck NWR (Fairfax County), Aquia Landing Park (Stafford County), Mulberry Point Marsh along the Rappahannock River (Richmond County), and Back Bay NWR and Nawney Creek (Virginia Beach).

The only confirmed breeding record in the Mountains and Valleys region was at Shenandoah Wetlands Bank (Augusta County). Although breeding could not be confirmed in the Piedmont region, there was one possible breeding record of two Least Bitterns in Charlotte County.

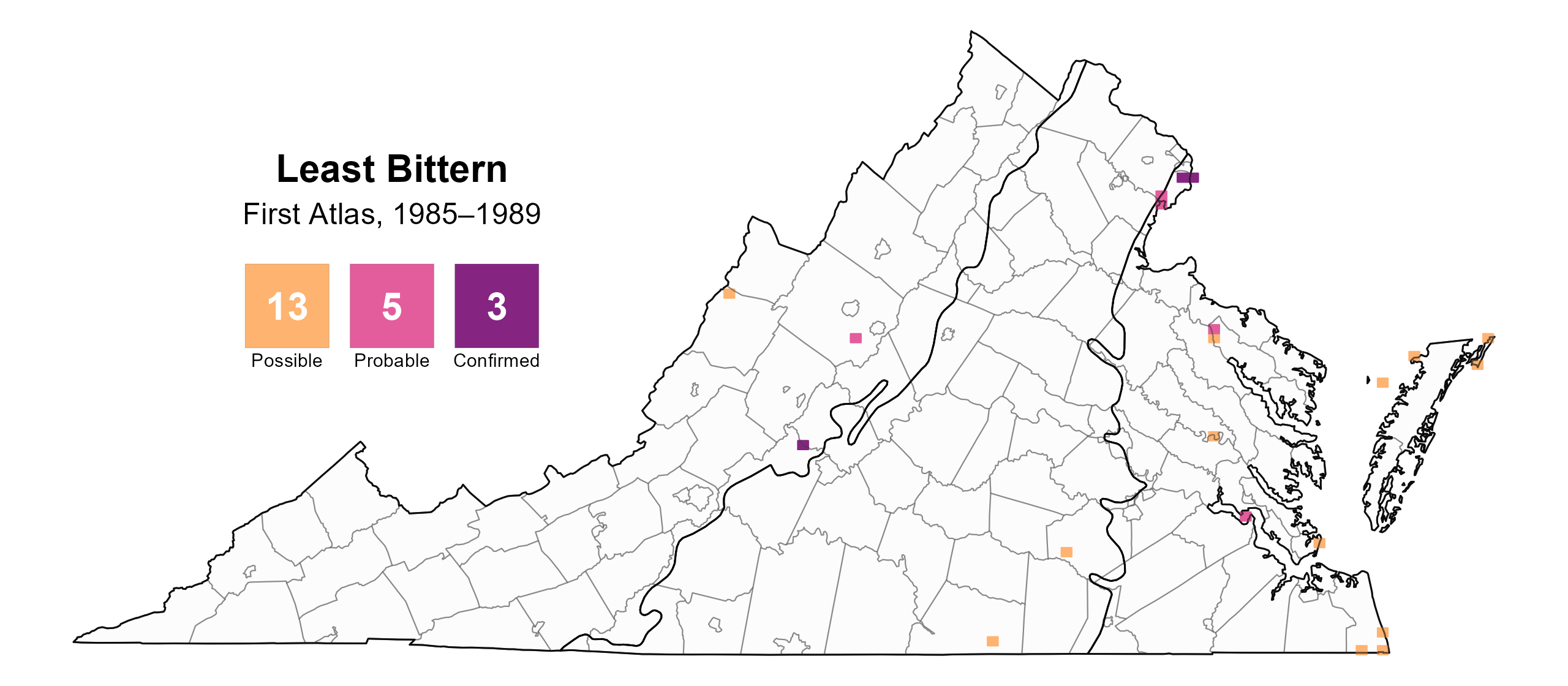

Despite the greater survey effort expended during the Second Atlas, the number and distribution of blocks with breeding observations did not change greatly from those during the First Atlas. However, access to marshes where Least Bitterns may breed, especially tidal marshes, remains a challenge for Atlas volunteers. In combination with the difficulty in detecting the species, this lack of access led to relatively few reports of what is most likely a more broadly distributed species.

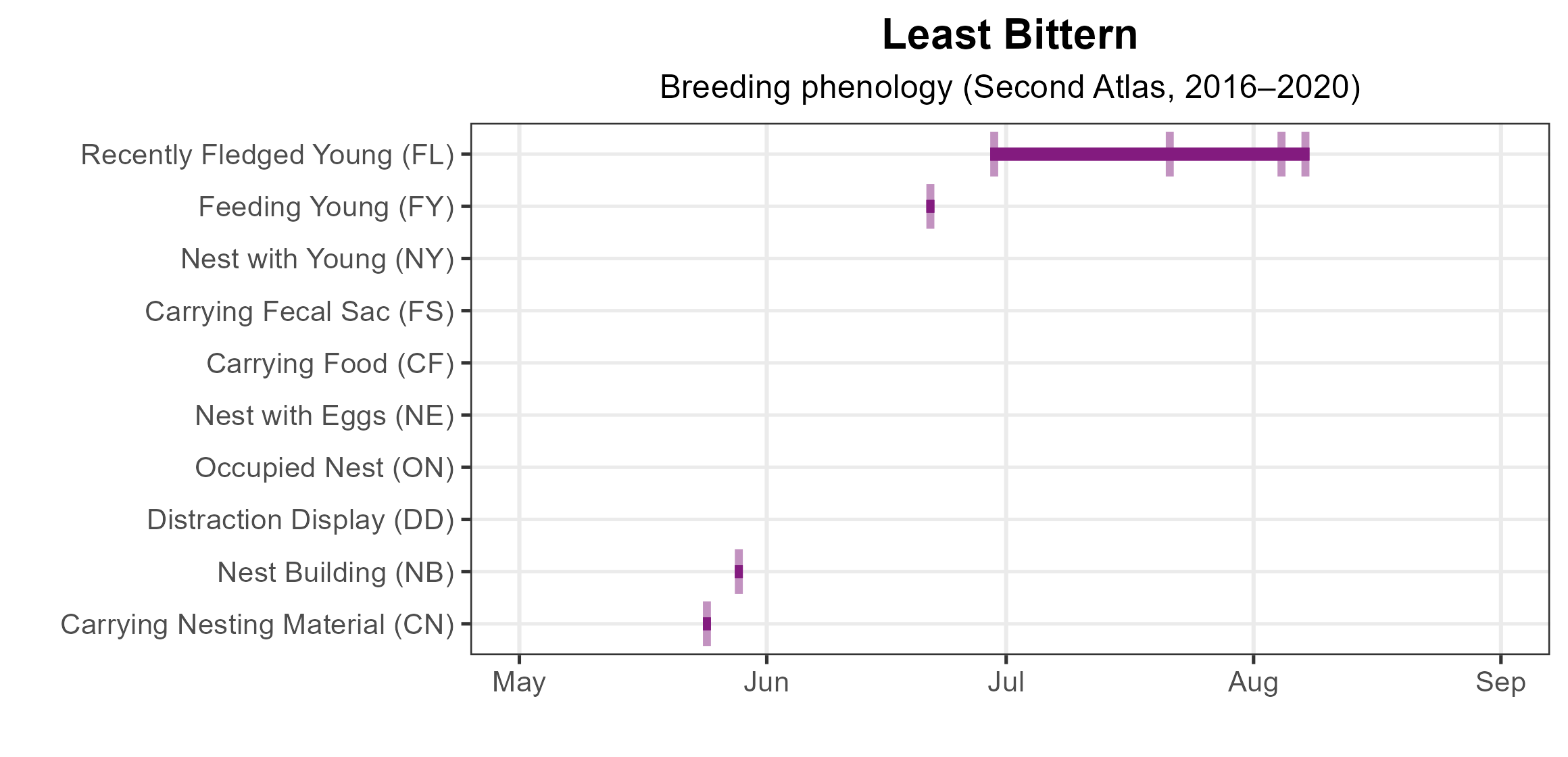

Because the species was so seldomly observed, it is difficult to describe its breeding phenology. Birds were observed building nests in late May and feeding young on June 21. Recently fledged young were observed from June 29 to August 7 (Figure 3). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Least Bittern, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Least Bittern breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Least Bittern breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Least Bittern phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Abundance could not be modeled because the species was not detected during Atlas point count surveys. There are also no credible population trend estimates from the North American Breeding Bird Survey as Least Bitterns are difficult to detect.

Conservation

The Least Bittern is considered an Assessment Priority Species in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan, indicating the need for more population-level information (VDWR 2025). Its secretive nature makes it difficult to detect even via targeted marsh bird surveys; it does not respond consistently to playback and tends to be detected when vocalizing or flushing (Sergio Harding, personal communication). Little is known about its true distribution or population status in Virginia or even its population trend at regional and continental scales. Targeted surveys and research should be implemented at a broad scale both within and outside of the Commonwealth to fill these knowledge gaps.

Least Bitterns are subject to the same threats as other birds of emergent marshes, including marsh loss through climate-induced sea-level rise and marsh subsidence. However, they are known to nest in the invasive common reed (Phragmites australis), such that the reed’s continued expansion may benefit the species (Bryan Watts, personal communication). Wetland conservation directed at higher priority marsh bird species will undoubtedly further improve the outlook for Least Bittern.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

eBird. (2025). eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. http://www.ebird.org.

Poole, A. F., P. E. Lowther, J. P. Gibbs, F. A. Reid, and S. M. Melvin (2020). Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.leabit.01.1.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M.D., B.D. Watts, and D.F. Brinker. (2007). Status review of Chesapeake Bay marsh lands and breeding marsh birds. Waterbirds 30:122–137.