Introduction

Seen across much of the Commonwealth during the winter months, the Hermit Thrush has one of the more limited breeding ranges of the four breeding “spotted thrushes” within Virginia. It breeds and is found year-round in a narrow band that follows the Appalachian Mountains through the Blue Ridge Mountains to southern Virginia, where it inhabits high-elevation northern hardwood and spruce forests (Laughlin et al. 2013; Dellinger et al. 2020). Easily identified via a reddish tail that contrasts with its brown upperparts, the Hermit Thrush nests on or near the ground, where it also spends much of its time foraging (Dellinger et al. 2020).

The Virginia breeding range of the Hermit Thrush overlaps with that of the Veery (Catharus fuscescens), another high-elevation forest thrush with similar nesting habits. Interestingly, the Veery is less elevation-dependent (Lessig 2008) and, at least in the Mount Rogers area and further south, prefers more open, shrubby forest than the Hermit Thrush (Dellinger et al. 2007), allowing the two species to co-occur in this region.

Breeding Distribution

As part of its broader expansion into the southern Appalachian Mountains (Dellinger et al. 2020), the Hermit Thrush is a relatively recent breeder in Virginia, with breeding individuals first observed at Mount Rogers in 1966 (Scott 1966). Hermit Thrushes are found only in high-elevation forests of the Mountains and Valleys region, where they are most likely to occur in August, Bath, Grayson, Highland, Rockingham, and Smyth Counties (Figure 1).

Due to a low number of breeding records, its distribution during the First Atlas and the change between Atlas periods could not be modeled. For more information on its distribution during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Hermit Thrush breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

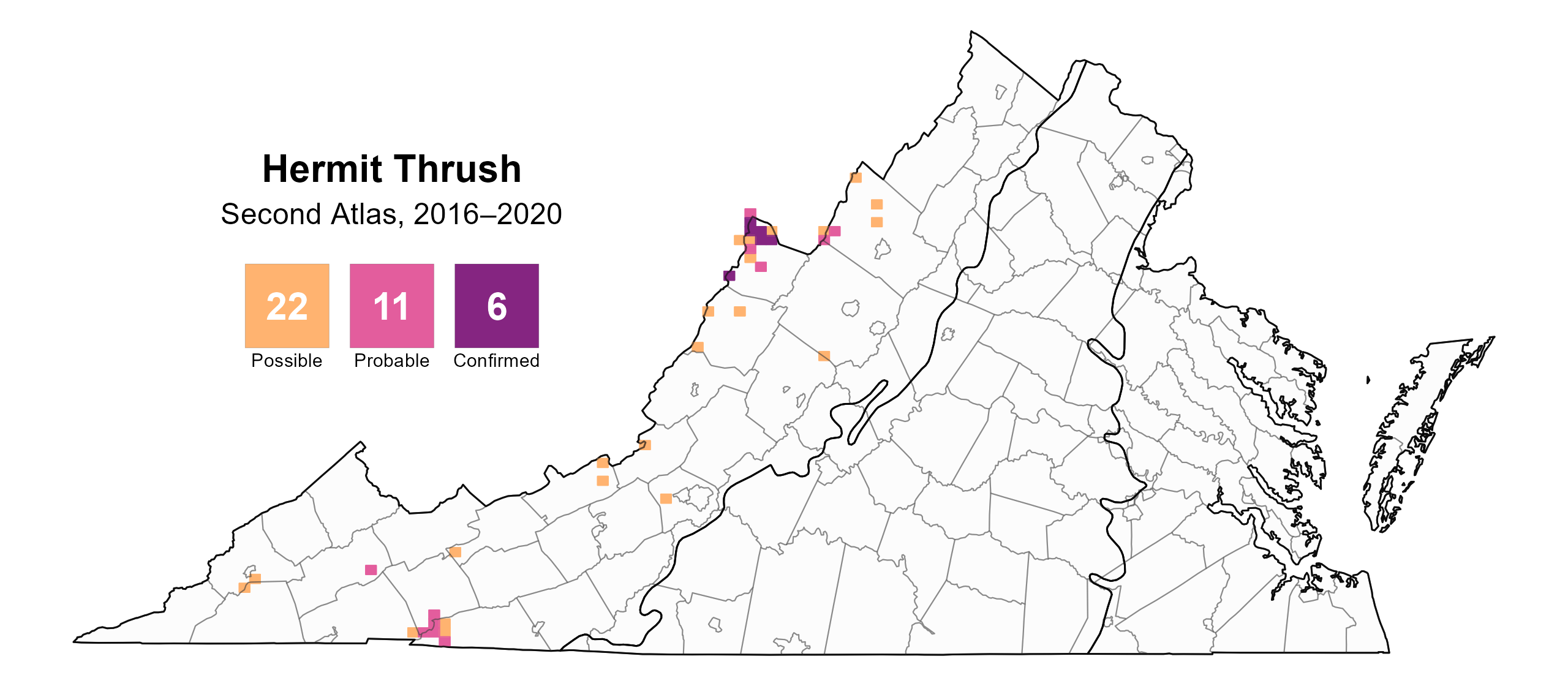

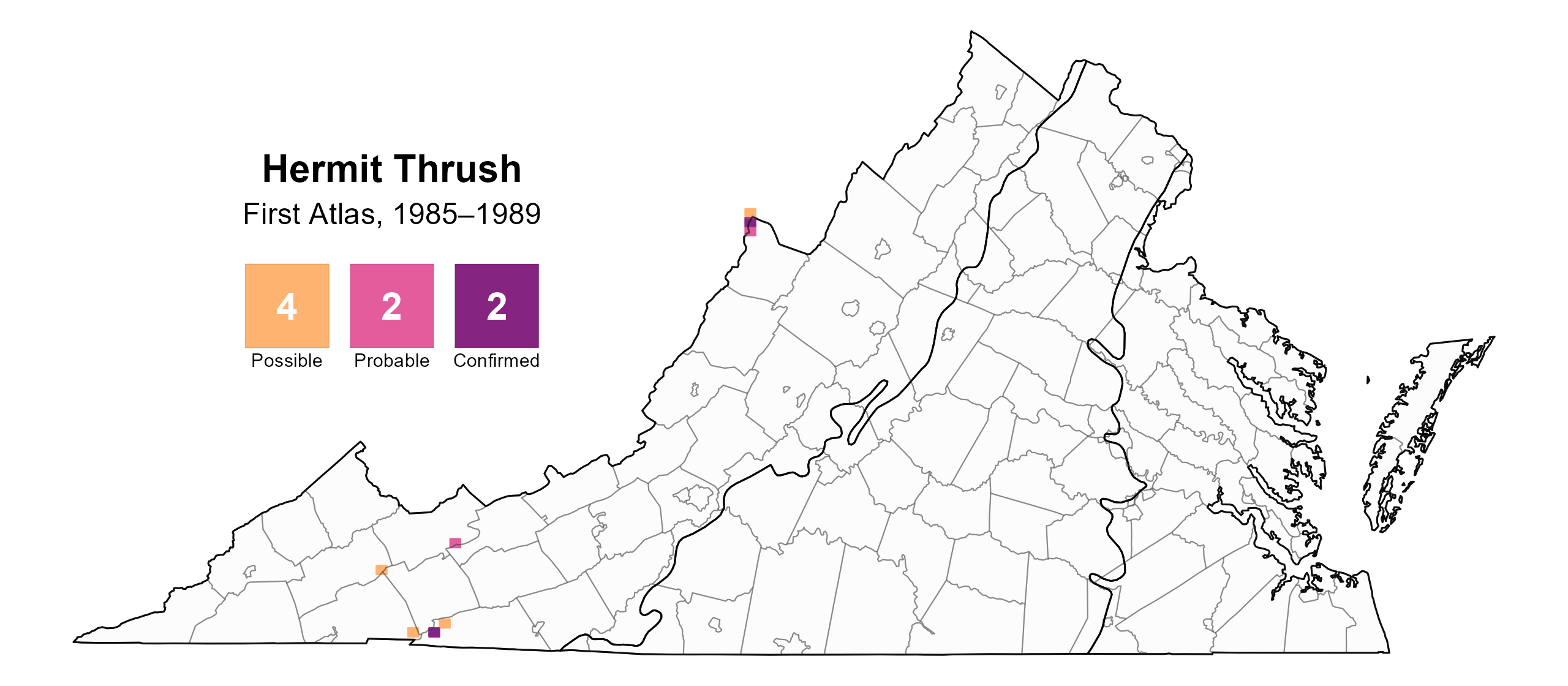

Hermit Thrushes were confirmed breeders in only six blocks, all within Highland County, and probable breeders in two additional blocks in Highland County and in nine blocks in five additional counties (Grayson, Rockingham, Russell, Smyth, and Washington) (Figure 2). The Hermit Thrush was reported from spruce, northern hardwood/deciduous stands, and mixed stands during the Second Atlas. During the First Atlas, breeding was confirmed in only two blocks, in Grayson and Highland Counties (Figure 3). The number of blocks in which the species was documented quadrupled between Atlases, and although greater survey effort during the Second Atlas may have contributed to this increase, these observations are also consistent with the species’ positive population trend within the Appalachian region (see Population Status section).

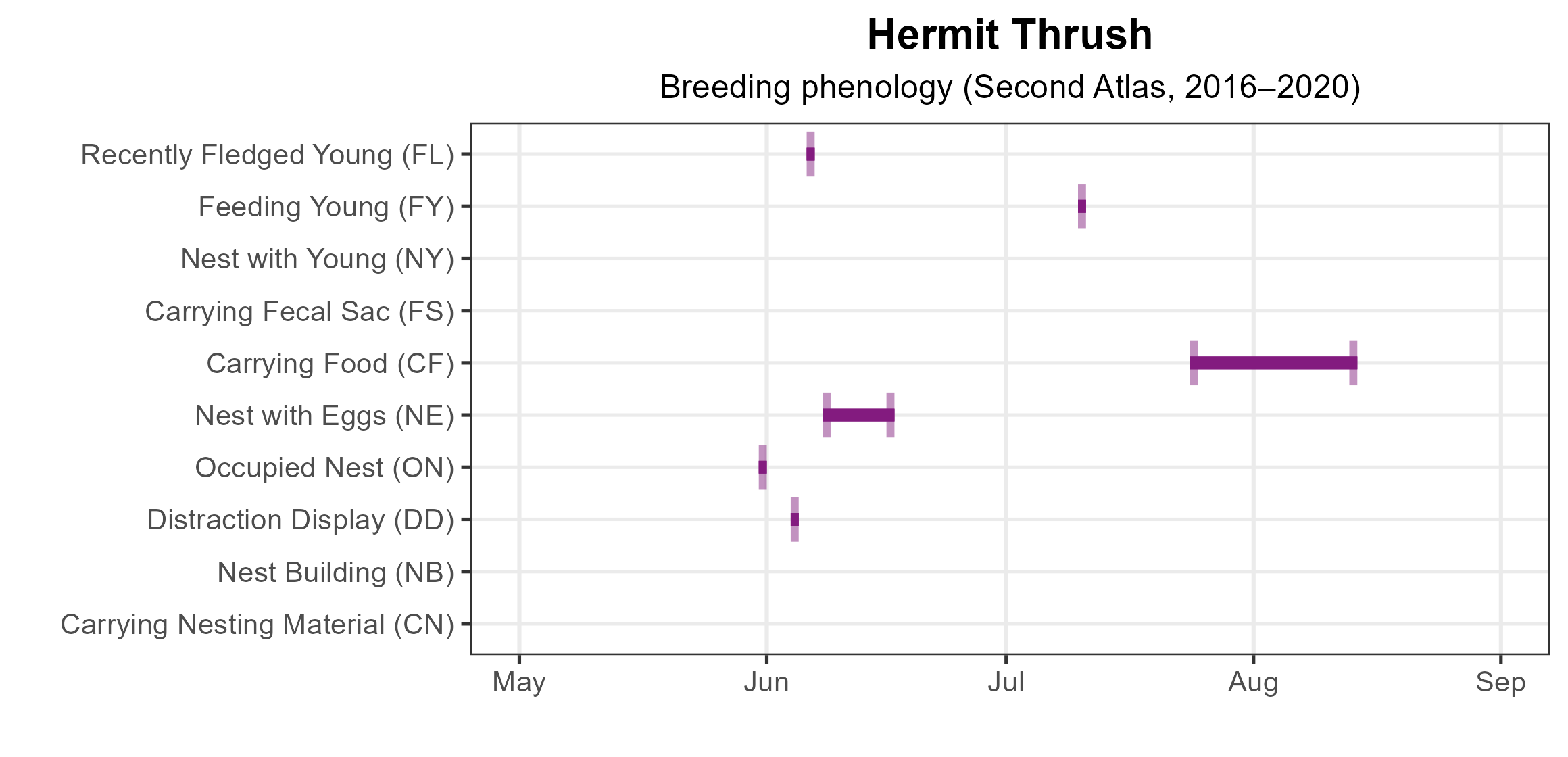

Breeding was confirmed as early as May 31 (occupied nests) and was also confirmed through observations of nests with eggs (June 8 – June 16), adults carrying food (July 24 – August 13), and recently fledged young (June 6) (Figure 4).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Hermit Thrush breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Hermit Thrush breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Hermit Thrush phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

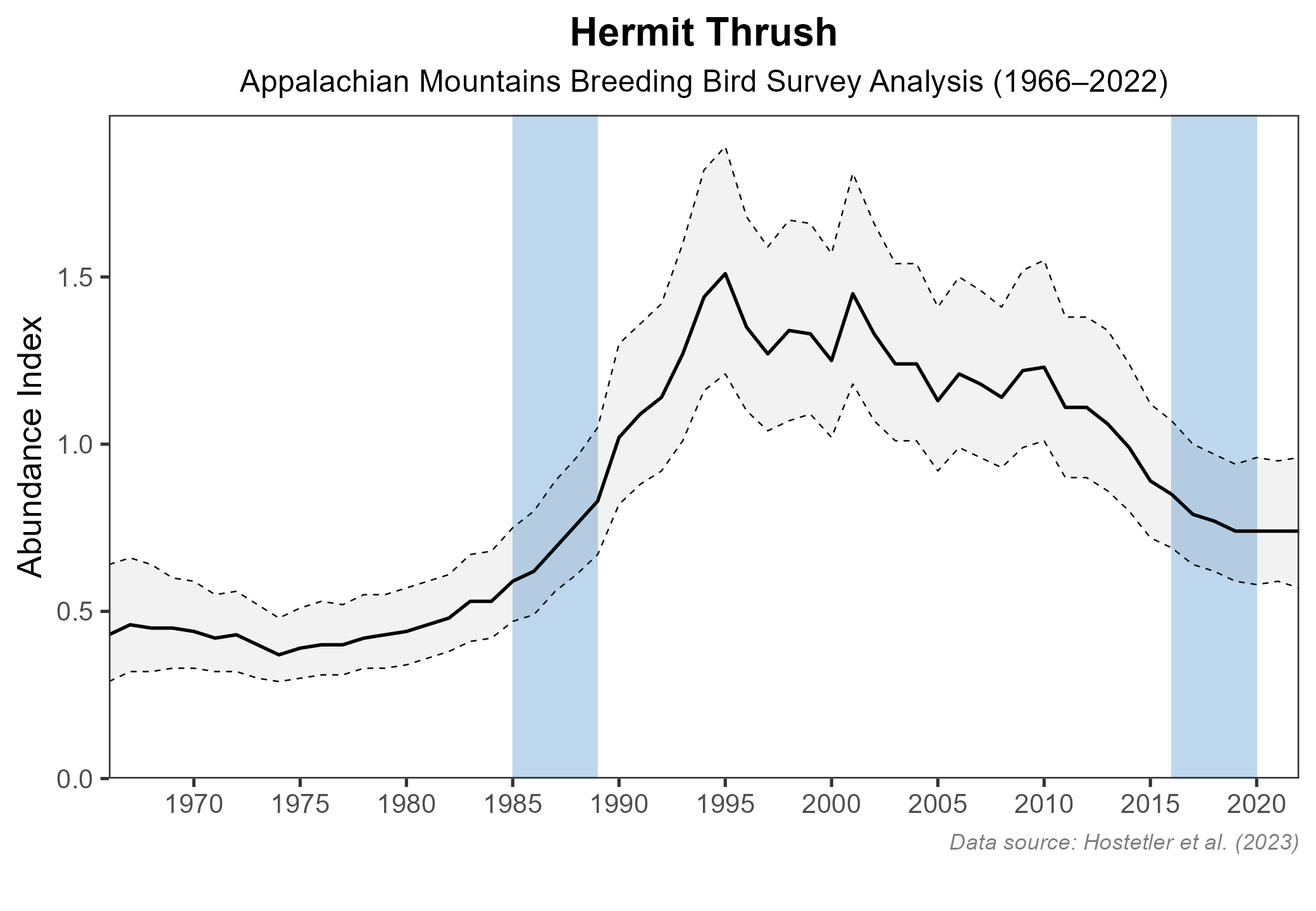

Hermit Thrushes were detected at only 14 points during the Atlas point count surveys, so an abundance model for the species could not be developed. The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not produce a credible population trend for Virginia, given the small number of routes on which the species has been detected. However, the BBS trend for the Appalachian Mountains region showed a significant 0.86% annual increase from 1966 to 2022 in that region, with a nonsignificant increase of 0.34% per year between Atlas periods (1987–2018) (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). These trends were paralleled in Virginia by increases in the number of Hermit Thrush detections on forays by the Virginia Society of Ornithology in Highland County between 1975 and 2003 (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Figure 5: Hermit Thrush population trend for the Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Despite a positive population trend and an increase between Atlases in the number of sites where it was observed, the Hermit Thrush is believed to have a small population and a very limited range within Virginia, making it vulnerable to external threats. As such, it is classified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need Tier III (High Conservation Need) in Virginia’s 2025 Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025).

A 2005–2007 Virginia study of high-elevation bird communities found Hermit Thrushes breeding at elevations between 3,670 and 5,466 ft (1,119 m and 1,666 m, respectively) (Lessig 2008). Within that range, the species was not widely distributed, occurring at only eight percent of over 1,000 points and only seven of 36 sites (Lessig 2008). Neither this study nor the Atlas likely documented the full geographic distribution of Hermit Thrush within Virginia; thus, building on these efforts by collecting additional data will provide more comprehensive information upon which to base conservation decisions.

In Virginia, the number and size of high-elevation forest patches in an area are more important to Hermit Thrush than the quality of those forests (Lessig 2008), suggesting that the species may be vulnerable to forest fragmentation (Dellinger et al. 2020). Sites that are particularly important for the species, based on these criteria, are Reddish Knob and surrounding sites (in Augusta, Bath, Highland, and Rockingham Counties) and Mount Rogers and nearby areas (in Grayson and Smyth Counties) (Lessig 2008). In addition to these sites, a good number, though not all, of the high-elevation ranges where the Hermit Thrush breeds are on public lands, providing the thrush with protection from development. However, these isolated “islands” of habitat are vulnerable to rising temperatures from a changing climate, which may result in habitat loss and eventual range contraction of the species. For now, the Hermit Thrush is enjoying a period of continued population growth and expansion.

Beyond the breeding grounds, gaining a better sense of where Virginia’s Hermit Thrushes spend the winter will help to assess whether they may be exposed to additional threats as it is unknown whether Virginia’s breeders are permanent residents, migrate to other areas of the state, or migrate to winter elsewhere in the continental U.S.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Dellinger, R. L., P. B. Wood, P. D. Keyser (2007). Occurrence and nest survival of four thrush species on a managed central Appalachian forest. Forest Ecology and Management 243: 248–258.

Dellinger, R., P. B. Wood, P. W. Jones, and T. M. Donovan (2020). Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.herthr.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Laughlin, A. J., I. Karsai, and F. J. Alsop (2013). Habitat partitioning and niche overlap of two forest thrushes in the Southern Appalachian spruce-fir forests. The Condor 115: 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2013.110179.

Lessig, H. (2008). Species distribution and richness patterns of bird communities in the high elevation forests of Virginia. Master’s Thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Scott, F. R. (1966). Results of Abingdon foray, June 1966. The Raven 37:71–76.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.