Introduction

The shy, grassland-dwelling Henslow’s Sparrow advertises its presence with a brief hiccup. Despite its modest vocalization, the species is a prolific singer with the ability to vocalize well into the night (Herkert et al. 2020). Although it is easily overlooked, the sparrow is currently a rare sight in Virginia due to considerable population declines.

The identity and source of Henslow’s Sparrow populations on the East Coast are not completely understood. Individuals of the subspecies Centronyx henslowii susurrans formerly bred in coastal marshes, including in tidal salt and brackish marshes in the Virginia Coastal Plain region (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; Wilson and Watts 2012). In the late 1800s, deforestation led to an expansion of the subspecies C. h. henslowii, which had been concentrated in the central prairies of the Midwest, into eastern states (Herkert et al. 2020). It is unclear whether Virginia’s inland population, which bred away from marsh habitats, was limited to the midwestern subspecies or included individuals from the coastal subspecies (Wilson and Watts 2012). This question is the subject of ongoing research.

Breeding Distribution

During the Second Breeding Bird Atlas, there were too few breeding observations to develop distribution models for Henslow’s Sparrow. Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

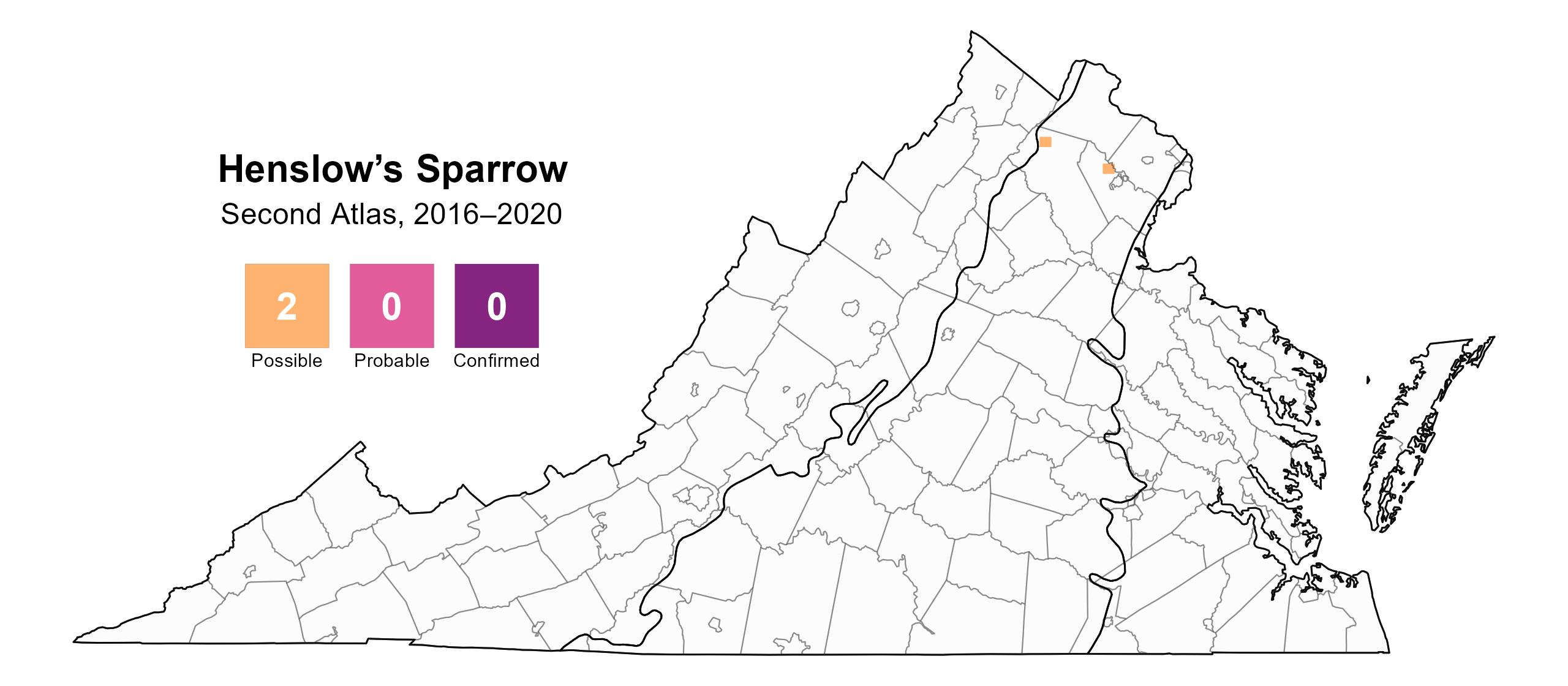

Although no Henslow’s Sparrows were confirmed as breeders during the Second Atlas, they were noted as possible breeders in two counties (Figure 1). A small population of the species was documented at Manassas National Battlefield Park in Prince William County through targeted surveys between 2016 and 2018. In 2020, one or two singing individuals were discovered on private property in Fauquier County.

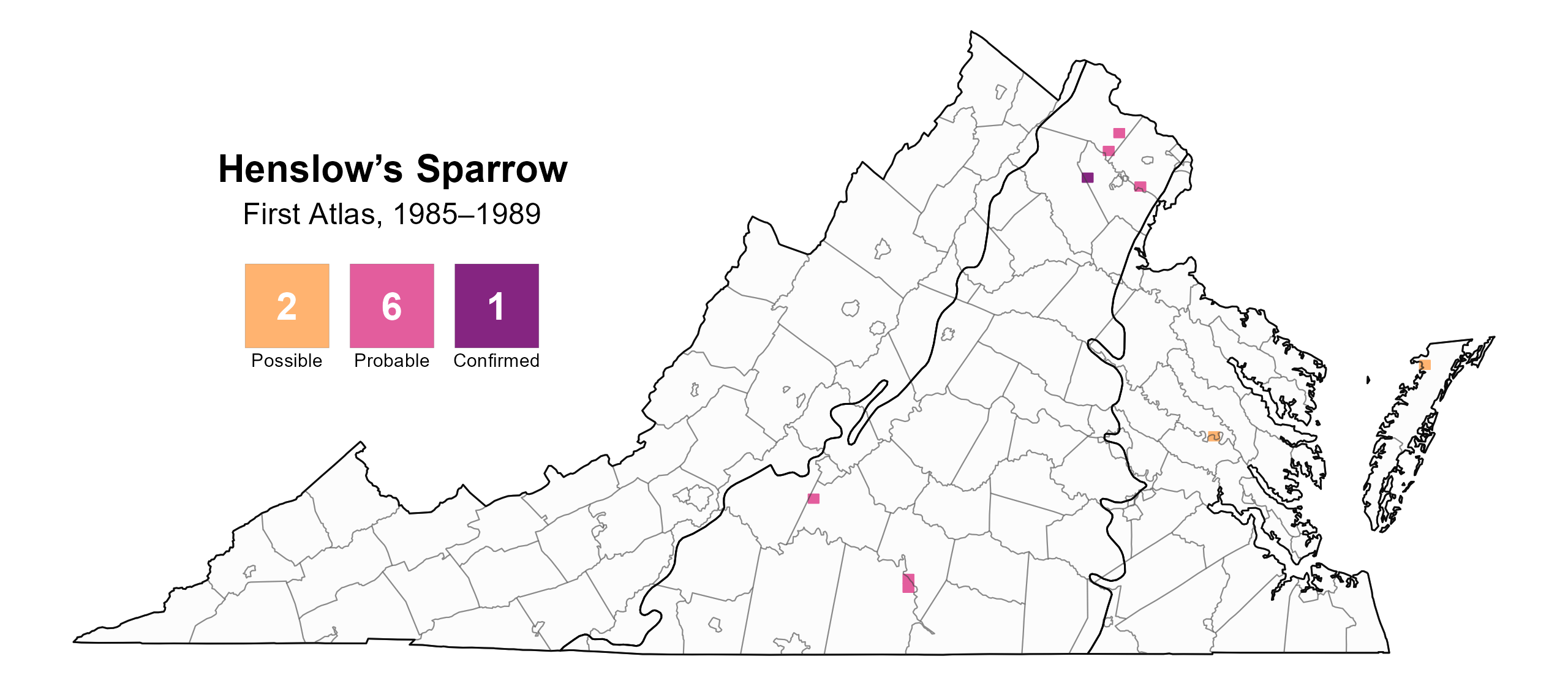

During the First Atlas, Henslow’s Sparrows were documented in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions. The species was a confirmed or probable breeder in Campbell, Halifax, Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William Counties and a possible breeder in Accomack and New Kent Counties (Figure 2). In the time since the First Atlas, populations have dwindled in all regions of the state. By the late 1990s, it had vanished from all but a few sites and was a reliable breeder only at the Radford Army Ammunition Plant (Pulaski County) in the Mountains and Valleys region (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Between Atlases, the already limited distribution of Henslow’s Sparrow diminished to near absence.

For more general information on the breeding habits of Henslow’s Sparrow, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Henslow’s Sparrow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Henslow’s Sparrow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Population Status

Given its rarity, Henslow’s Sparrow was not detected during the Atlas point count surveys. Because of its relatively low abundance along routes of the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), no credible BBS trends could be estimated for the species at any geographic scale; however, populations of the species are generally believed to be declining in the eastern United States.

The decline in the species in Virginia has been documented anecdotally. Although it used to be considered common in Virginia’s Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions and locally common in the Mountains and Valleys region (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), Henslow’s Sparrow lost ground in the Commonwealth in the 1970s and was reported as scattered pairs or individuals by the 1980s and 1990s (Wilson and Watts 2012).

Conservation

Due to its substantial decline in the Commonwealth, Henslow’s Sparrow is designated as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan, indicating that it faces an extreme risk of becoming extirpated (VDWR 2025). For the same reasons, it is listed as threatened at the state level.

Coastal populations that nested in the higher grounds of tidal marshes may have declined due to loss of habitat to invasive common reed (Phragmites australis) and predation pressure from foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and raccoons (Procyon lotor) from nearby uplands (Wilson and Watts 2012). The species was last reported from the Saxis Marsh area in Accomack County in 1995 (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007) and is believed to have been lost from its former marshland range. Elsewhere within the Coastal Plain, Henslow’s Sparrows were detected during large clearcuts in Sussex County in 1996 (Watts et al. 1998), but these may have been the last breeding-season records for the region.

Henslow’s Sparrow is still reported sporadically further inland. There, the species has specific and ephemeral needs. In Virginia, Henslow’s habitat is large weedy grasslands, which may include broomsedge (Andropogon spp.) (Wilson and Watts 2012) interspersed with small shrubs. Much of the decline in the inland population is thought to be due to the loss of agricultural and early successional grassland habitats to development resulting from the expansion of urban areas (Jaster et al. 2022). More importantly, the agricultural landscape has changed across the state, especially in the Piedmont region, from smaller farms to larger farms with row cropping that is not suitable habitat for many grassland species (October Greenfield, personal communication).

Due to its rarity in Virginia, surveys to document and study breeding populations are integral to developing a broader conservation strategy. These should include surveys at sites of known historic and recent occurrences. The Radford Army Ammunition Plant near Dublin in the Mountains and Valleys region has hosted a small breeding population since 1997 (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). A July 2009 observation of three individuals may have been the last detection there of the species (VSO 2009), as no birds were found during surveys there by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) in 2020 and 2024.

The species has also been monitored at the Manassas National Battlefield Park, with birds present at five to six points annually between 2016 and 2018. Henslow’s Sparrow was not detected during subsequent surveys through 2024.

In 2020, the discovery of Henslow’s Sparrow in Fauquier County in the Piedmont region by Virginia Working Landscapes (VWL) was followed by an expanded survey effort in 2022. VWL documented three territories with singing males, two with a second adult and one with a juvenile. VWL Surveys in 2024 recorded the first nest with eggs in decades and led to the banding of fledged young.

In the Appalachian Mountains, Henslow’s Sparrows also occur in small numbers on reclaimed strip mines. Some of these sites linger as sparse, weedy grasslands through a process known as “arrested succession” (Groninger et al. 2017), which can potentially provide decades of Henslow’s Sparrow habitat, as has been the case for multiple sites in western Maryland. Some comparable habitat may exist in southwestern Virginia, where the species has not been detected. Because Henslow’s Sparrow can be easily missed, surveys of the broader grassland bird community should include a component targeted at detecting the species.

The Henslow’s Sparrow can benefit from conservation work aimed at the broader suite of grassland birds on working agricultural lands in Virginia, such as that being conducted on pastures and hayfields by VWL and partners through the Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative. However, because it is rare, recovering the species will require additional actions such as those outlined in the species’ Status Assessment and Conservation Plan (Cooper 2012). These actions include determining the species’ current distribution throughout its breeding range; improving our understanding of how its populations are affected by different management actions; and protecting, restoring, and maintaining the grassland habitats needed to sustain stable populations. The sparrow’s wintering habitat, which is wholly contained within the southeastern U.S., also requires conservation focus (Cooper 2012). Determining where Virginia’s Henslow’s Sparrows spend the nonbreeding season could be challenging, however, given that so few individuals are currently documented in the Commonwealth.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Cooper, T.R. (2012). Status assessment and conservation plan for the Henslow’s Sparrow (Ammodramus henslowii). Version 1.0. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bloomington, MN, USA. 126 pp.

Groninger, J., J. Skousen, P. Angel, C. Barton, J. Burger, and C. Zipper (2017). Chapter 8: Mine reclamation practices to enhance forest development through natural succession. In The Forestry Reclamation Approach: Guide to Successful Reforestation of Mined Lands (M. B. Adams, Editor), 1–7.

Herkert, J. R., P. D. Vickery, and D. E. Kroodsma (2020). Henslow’s Sparrow (Centronyx henslowii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.henspa.01.

Jaster, L. A., W. E. Jensen, W. E. Lanyon, and S. G. Mlodinow (2022). Eastern Meadowlark (Sturnella magna), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (P. Pyle and N. D. Sly, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.easmea.01.1.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Virginia Society of Ornithology (VSO) (2009). Summer records June–July 2009. Virginia Birds 6.

Watts, B. D., M D. Wilson, D S. Bradshaw, and A. S. Allen (1998). A survey of the Bachman’s Sparrow in Southeastern Virginia. The Raven 69:9-14.

Wilson, M. D., and B. D. Watts (2012). The Virginia avian heritage project: a report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR 12-04. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA. 48 pp.