Introduction

The Eastern Warbling-Vireo is a migratory bird found in open riparian landscapes with mature deciduous trees in Virginia. Its name is fitting, as its sweet, meandering song is more distinctive than its plain coloration and tendency to remain unseen in the treetops. In addition to its cryptic appearance, the species is uncommon in Virginia, which is at the edge of its range. Eastern Warbling-Vireos arrive in late April, typically traveling by land around the Gulf of Mexico rather than crossing it directly as many other neotropical migrants do (Gardali and Ballard 2020).

The Eastern Warbling-Vireo is an uncommon migrant throughout the Commonwealth that breeds in mature woodlands along streams, ponds, and rivers. Its preference for open, park-like spaces means it can also be found in other habitat types with trees and open space, including urban parks, orchards, farms, campgrounds, and golf courses (Gardali and Ballard 2020; LeClerc and Cristol 2005). Virginia and western North Carolina are at the southeastern edge of the species’ breeding range in the east (Gardali and Ballard 2020).

In 2025, based on physical characteristics, ecology, and genetic data, the eastern subspecies of Warbling Vireo, Vireo gilvus gilvus, which occurs in Virginia, was split from western populations (Gardali and Ballard 2020; Carpenter et al. 2021, Chesser et al. 2025). The species is now known as Eastern Warbling-Vireo.

Breeding Distribution

Eastern Warbling-Vireos are found in all regions of the state, albeit only in scattered locations away from the Mountains and Valleys and northern Piedmont regions. It is most likely to occur in the Shenandoah Valley, particularly along the Shenandoah River (Figure 1). The species is virtually absent from the southern Piedmont region.

The likelihood of Eastern Warbling-Vireos occurring in a block increases in areas with a greater proportion of forested, agricultural, and developed land cover, given its ability to use these habitat types equally. This species is less likely to occur where there is a substantial amount of shrubland and grassland habitat, indicating a need for mature forest over scrub. Additionally, its likelihood of occurring is negatively associated with large forest patches, indicating that expansive, contiguous forest is slightly less likely to contain the species than smaller patches.

Overall, the Eastern Warbling-Vireo’s likelihood of occurrence during the Second Atlas was similar to that during the First Atlas (Figures 1 and 2), remaining constant throughout most of the state (Figure 3). However, its probable occurrence increased slightly on the Eastern Shore and decreased in the most southwestern corner of the Mountains and Valleys region with some small potential areas of decrease in the southern Piedmont region.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Eastern Warbling-Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Eastern Warbling-Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Eastern Warbling-Vireo change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

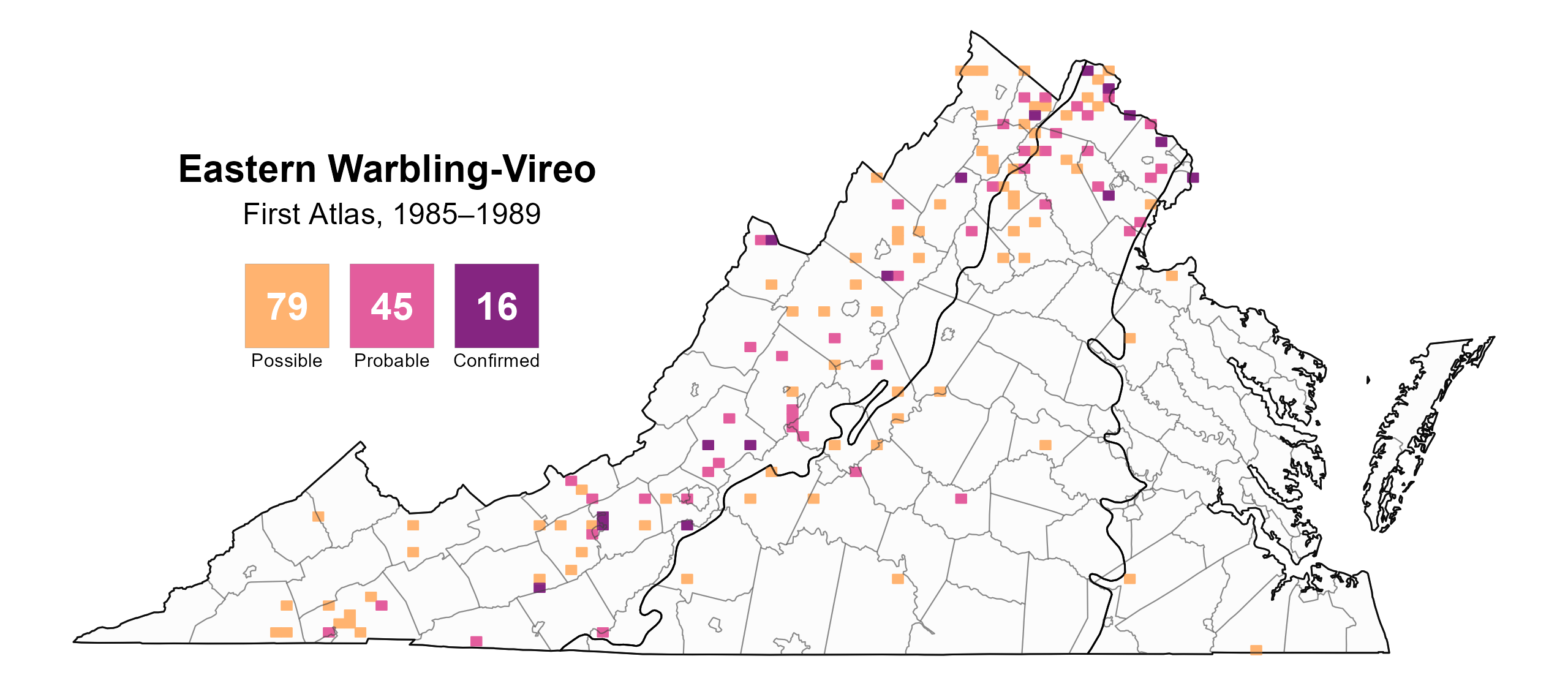

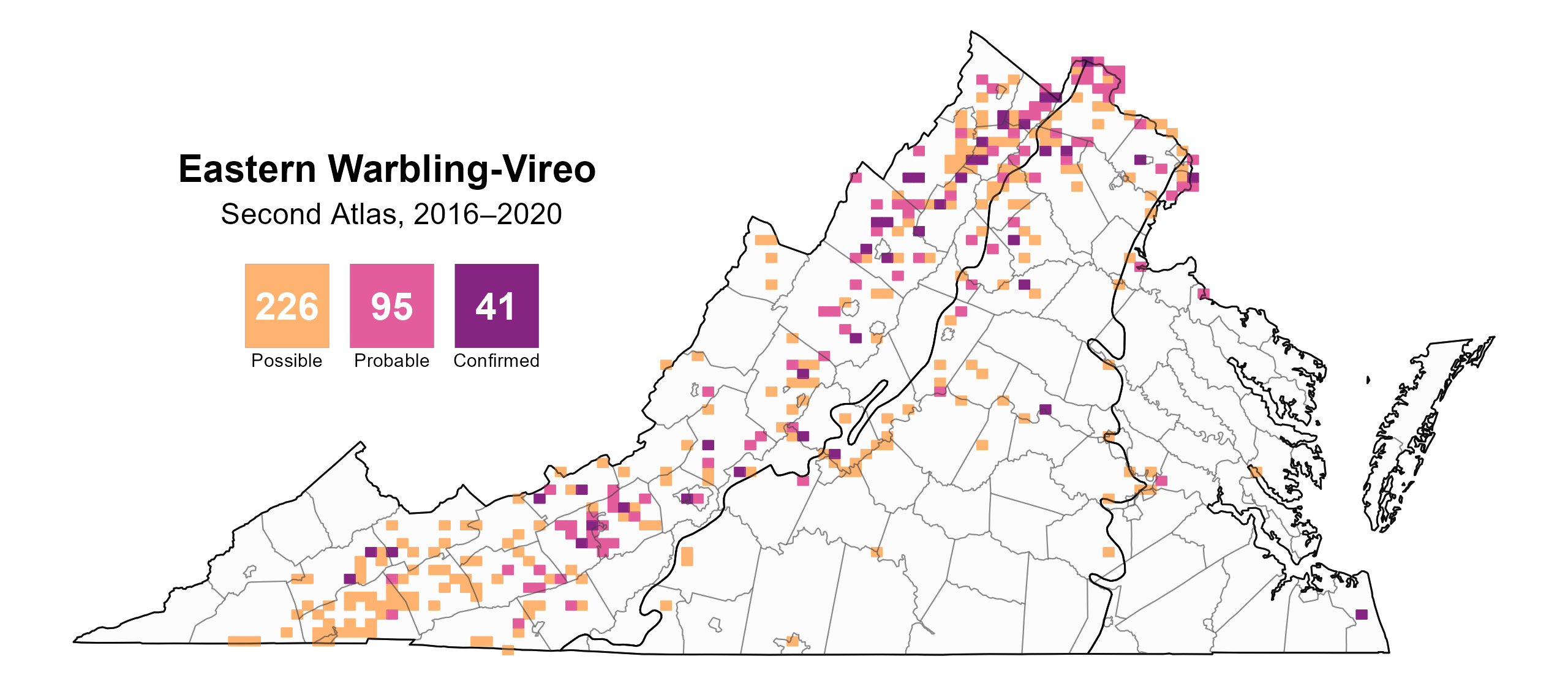

Eastern Warbling-Vireos were confirmed breeders in 41 blocks and 25 counties and probable breeders in an additional 15 counties (Figure 4). Sightings at all levels, confirmed, probable, and possible, were concentrated along major waterways and their tributaries: the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers in the northern Piedmont and Valley and Ridge regions; the Rivanna and James Rivers in the central Piedmont region; and the New and Holston Rivers in southwestern Virginia. Confirmations were rare in the Coastal Plain, with one extreme southeastern record in suburban Virginia Beach and several birds breeding along the Potomac River at Belle Haven Park and Dyke Marsh (Fairfax County). The species appears likely to be absent as a breeder from the Cumberland Mountains. Breeding observations followed a similar pattern during the First Atlas (Figure 5).

Nests are often placed extremely high in trees (Gardali and Ballard 2020), making them difficult to locate and observe. During the Second Atlas, breeding was confirmed from April 29 when adults were observed nest building through August 5 (recently fledged young) (Figure 6). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Eastern Warbling-Vireo, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Eastern Warbling-Vireo breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Eastern Warbling-Vireo breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Eastern Warbling-Vireo phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

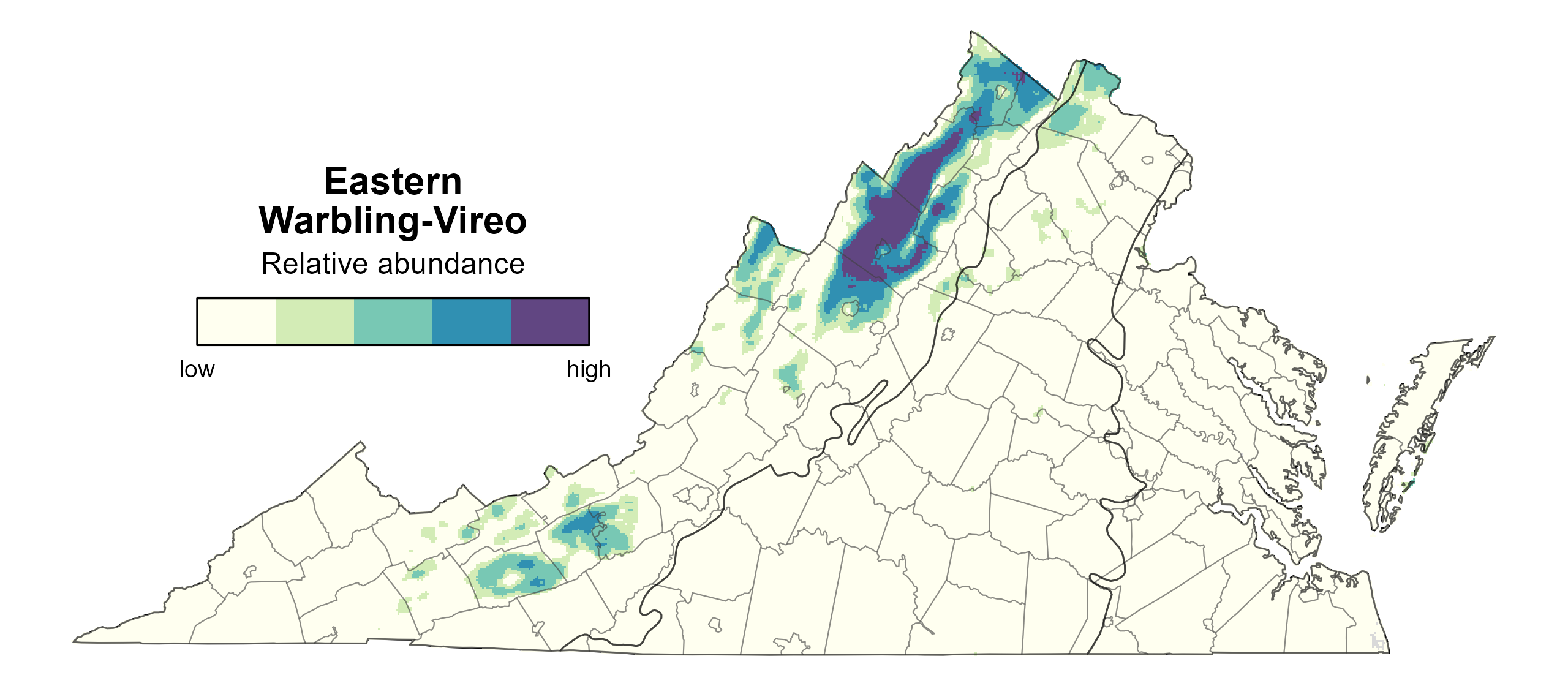

Eastern Warbling-Vireo relative abundance was only estimated for the Piedmont and Mountains and Valleys regions because there were too few detections in the Coastal Plain region during point count surveys. Their highest relative abundance levels were estimated to be in the Shenandoah Valley, where there is a mixture of agricultural and forest cover (Figure 7). The species was at extremely low abundance levels throughout the rest of its predicted range.

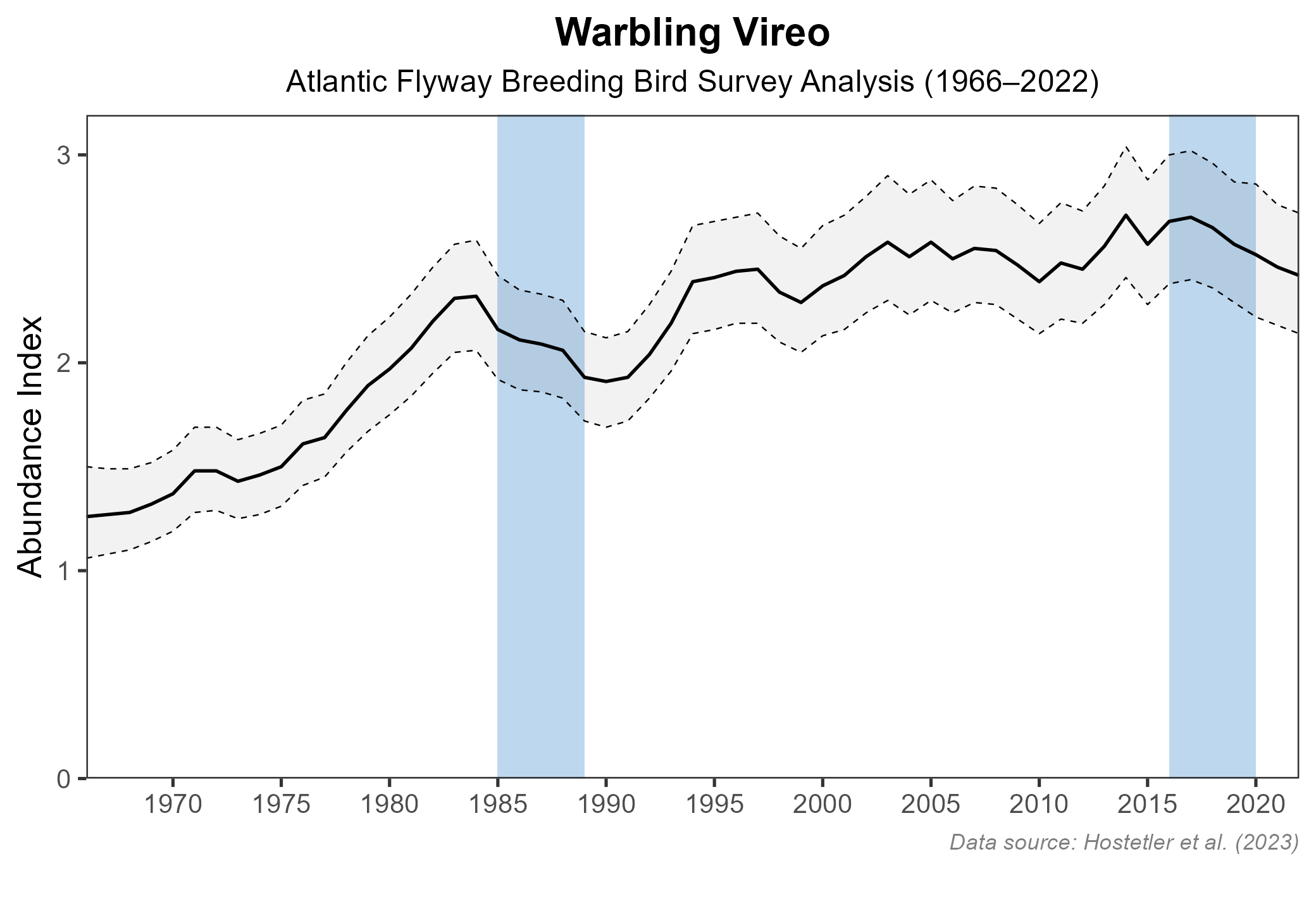

The total estimated Eastern Warbling-Vireo population in the state is approximately 36,000 individuals (with a range between 16,000 and 84,000). The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data do not cover Eastern Warbling-Vireo well in Virginia. At the Atlantic Flyway scale, the species has undergone a significant increase of 1.17% per year from 1966-2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend for the Atlantic Flyway showed a smaller significant increase of 0.77% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Eastern Warbling-Vireo relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Figure 8: Eastern Warbling-Vireo population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because Eastern Warbling-Vireo populations are stable, this species is not the focus of any conservation efforts in Virginia. However, because Virginia is at the southeastern edge of the species’ range, climate change may lead to range loss in the state as the Eastern Warbling-Vireo’s range shifts northward (National Audubon Society, 2025).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Carpenter, A. M., B. A. Graham, G. M. Spellman, J. Klicka, and T. M. Burg (2021). Genetic, bioacoustic and morphological analyses reveal cryptic speciation in the warbling vireo complex (Vireo gilvus: Vireonidae: Passeriformes). BioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.12.452121.

Chesser, R. T., S. M. Billerman, K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, B. E. Hernández-Baños, R. A. Jiménez, O. Johnson, N. A. Mason, and P. C. Rasmussen (2025). Check-list of North American Birds (online). American Ornithological Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/ornithology/ukaf015.

Gardali, Thomas, and Grant Ballard. 2020. Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World, edited by Alan F Poole and F B Gill. Ithaca, New York, USA: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.warvir.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

LeClerc, J. E., and D. A. Cristol (2005). Are golf courses providing habitat for birds of conservation concern in Virginia? Wildlife Society Bulletin 33:463–470.

National Audubon Society (2025). Survival by degrees: 389 bird species on the brink. https://www.audubon.org/climate/survivalbydegrees.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.