Introduction

Resembling a hefty sparrow with a yellow breast topped by a bold black mark on its throat, the Dickcissel can be difficult to pin down from one year to the next. Small breeding populations of this grassland bunting are variable in space and time in eastern states such as Virginia (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007), making it a much sought-after species by birders. Dickcissels breed in nearly any type of large grassland, including hayfields, pastures, and even brushy fallow fields (Sousa et al. 2022). There, males defend territories where they may mate with multiple females. Dickcissels are one of a very small percentage of North American songbirds with this type of breeding system, known as resource-defense polygyny.

Breeding Distribution

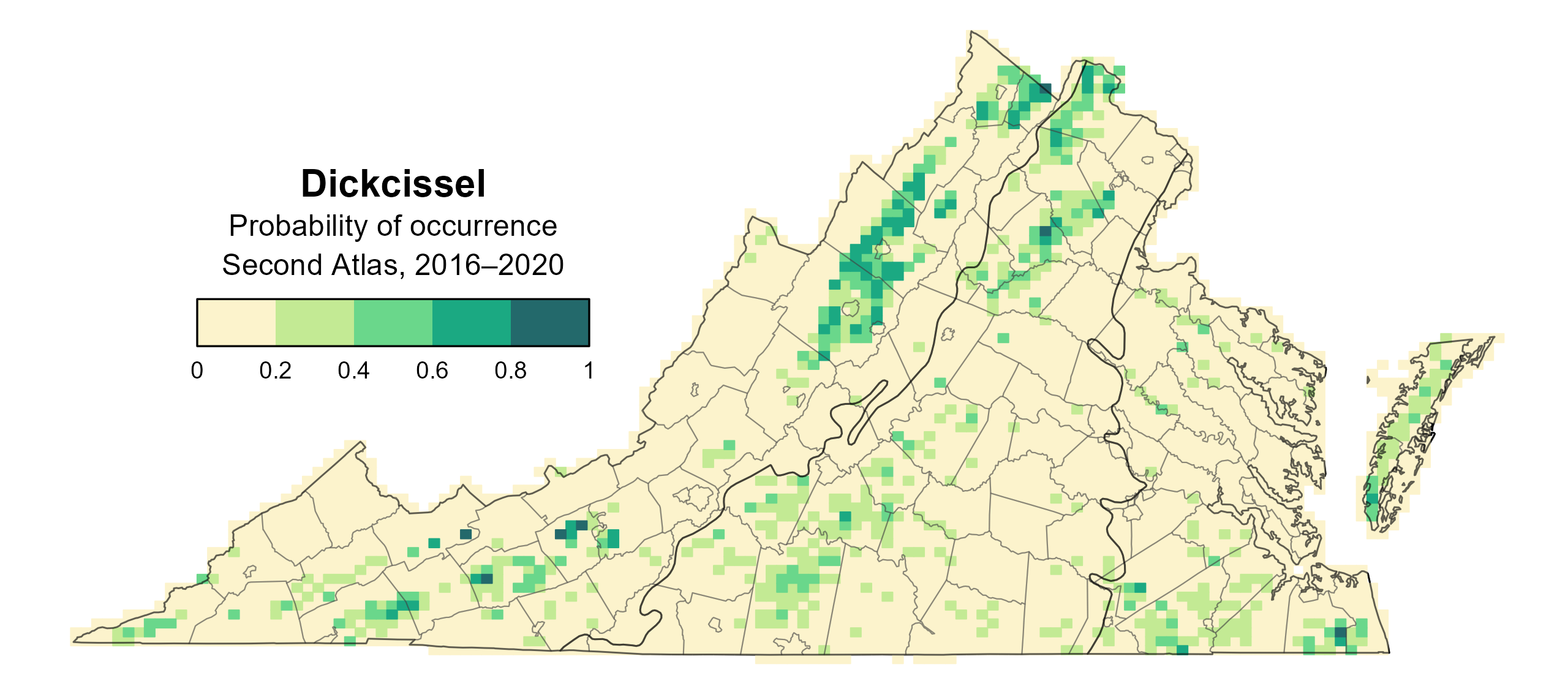

Dickcissels are relatively rare but widespread breeders in the state. They are most likely to occur in agricultural valleys of the Mountains and Valleys region, such as the Shenandoah Valley, and in the northern Piedmont region. They are moderately likely to occur in the southwestern Piedmont and southern Coastal Plain, as well as on the Eastern Shore (Figure 1). Dickcissels are most likely to be found in blocks with a greater proportion of agricultural lands (including hayfields and pastures) and, to a lesser extent, grassland and shrubland habitats. Dickcissels have a lower likelihood of occurring in blocks with a high proportion of forest cover, though that relationship is weak.

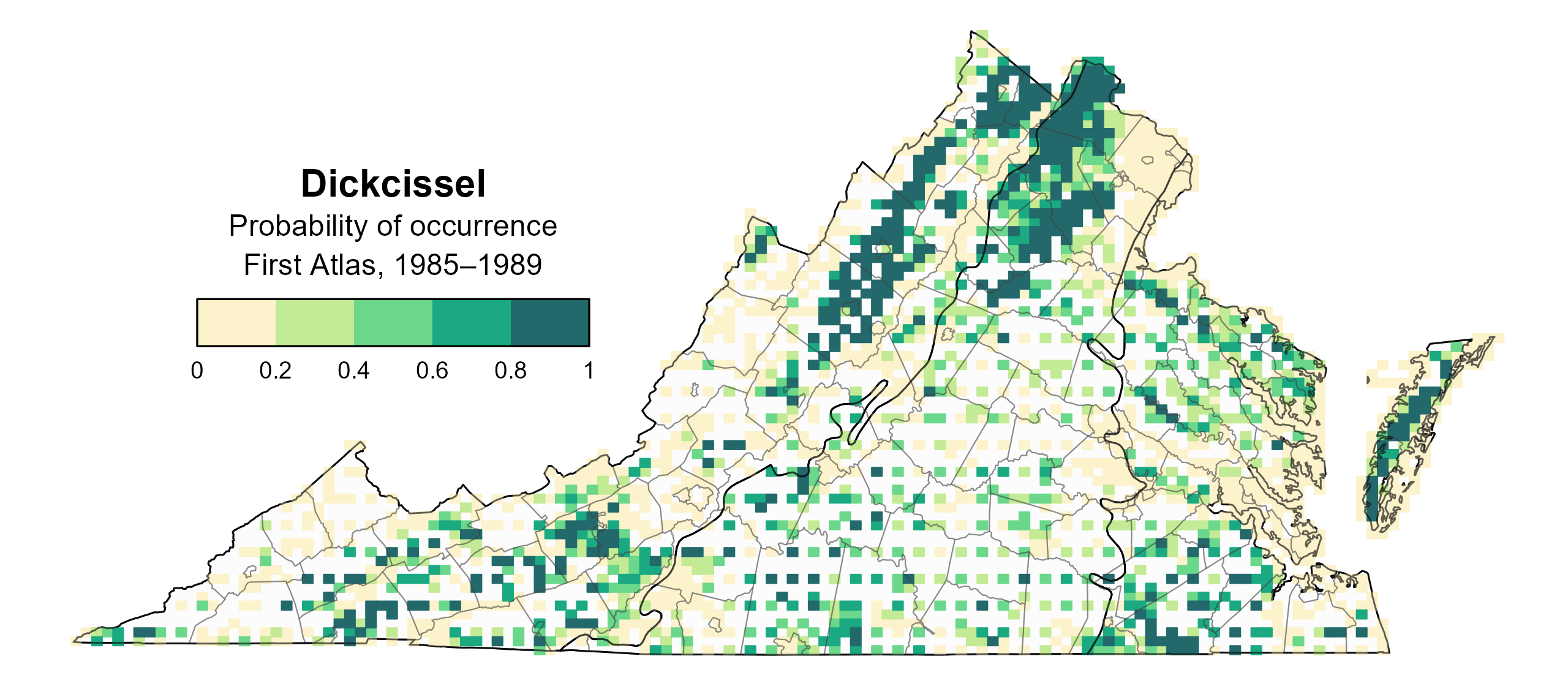

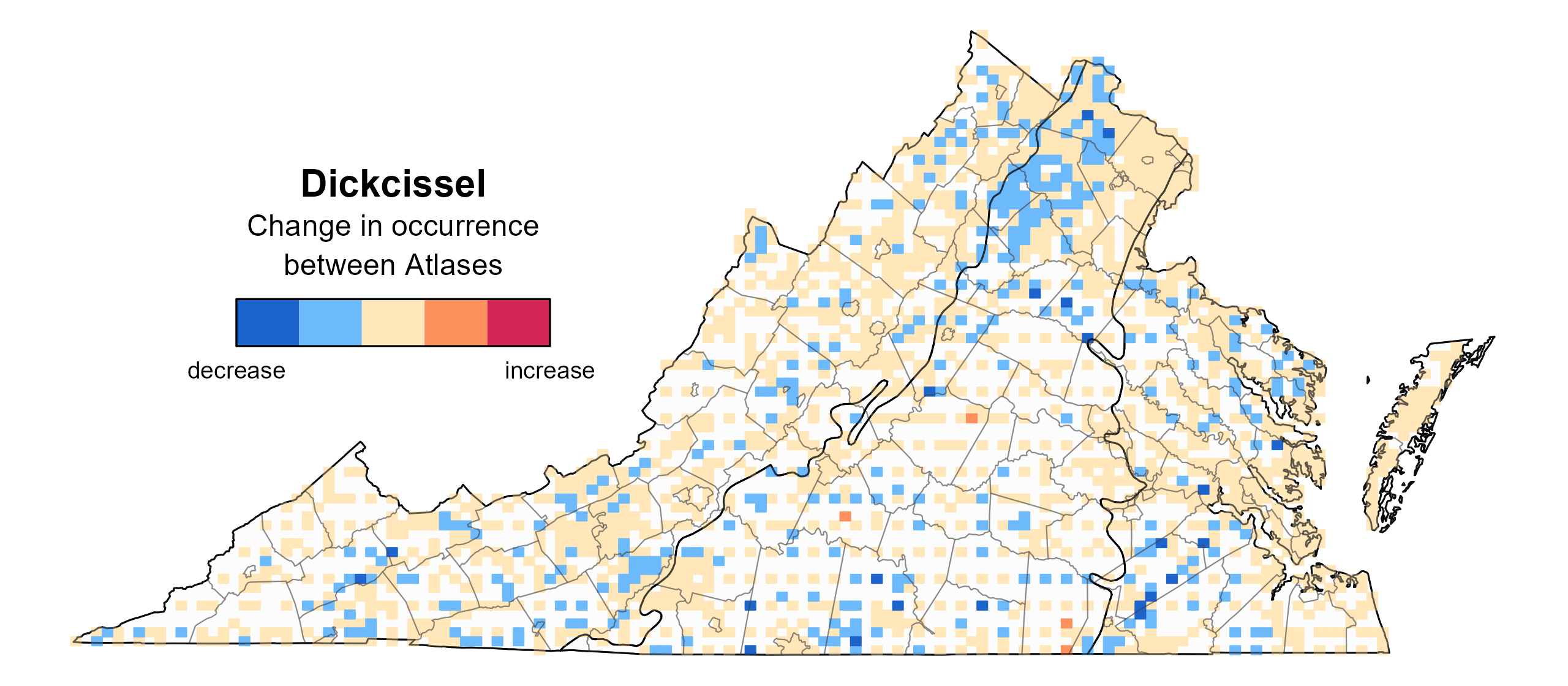

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), the Dickcissel’s likelihood of occurrence decreased in the northern Piedmont region, especially in a four-county area that included portions of Culpeper, Fauquier, Loudoun and Rappahannock Counties (Figure 3). Outside of this area, declines in occurrence were scattered in all three regions, which otherwise saw consistent occurrence between Atlases.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Dickcissel breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Dickcissel breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Dickcissel change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

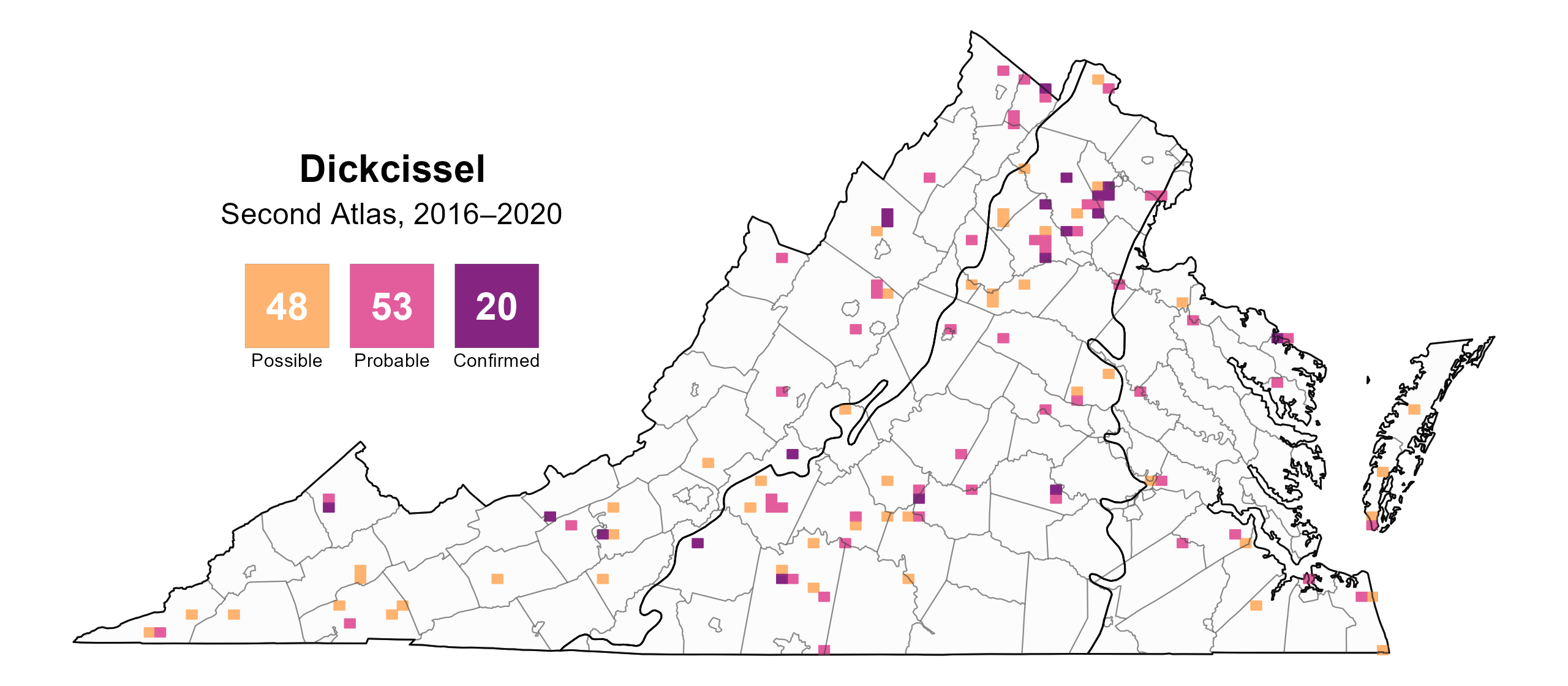

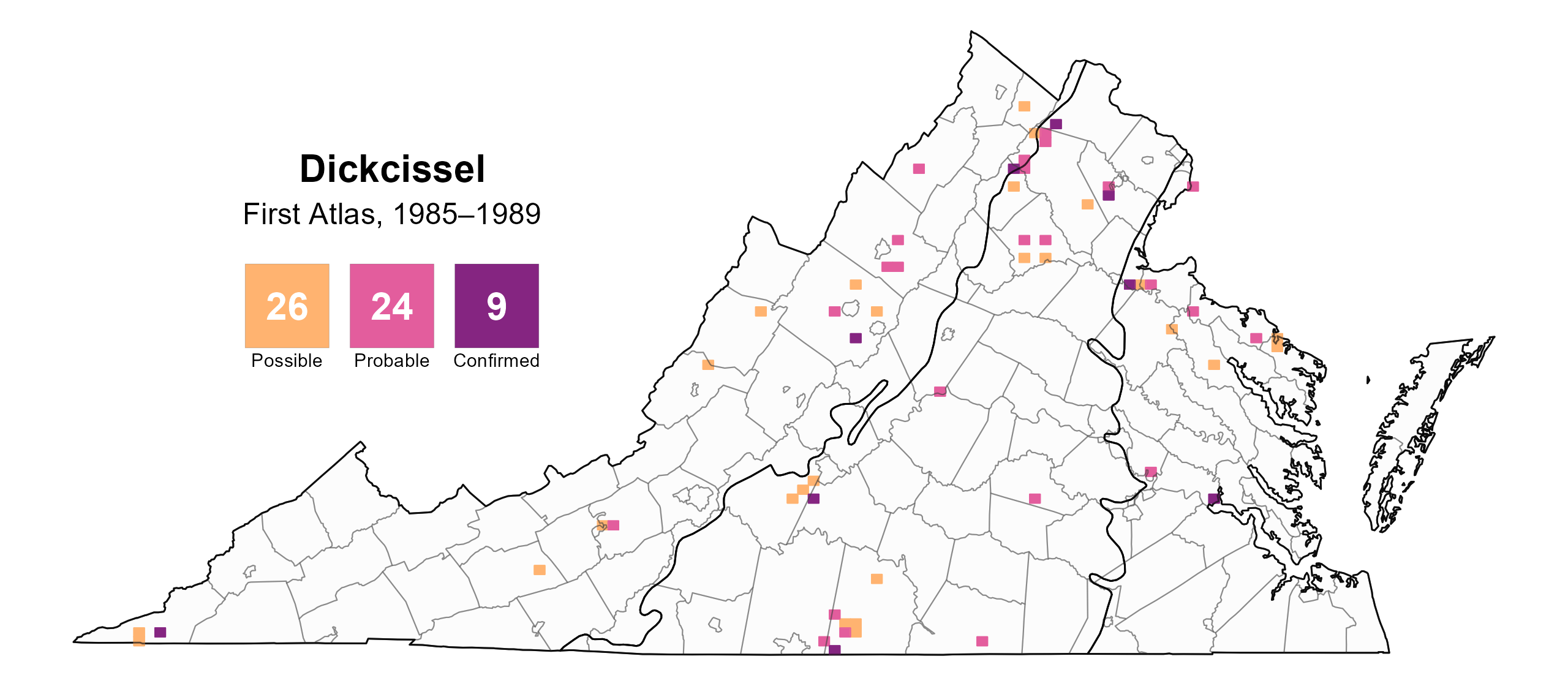

Dickcissels were confirmed breeders in 20 blocks and 14 counties and found to be probable breeders in 30 additional counties (Figure 4). Reports of Dickcissels were geographically patchy during both Atlas periods, likely owing to the Dickcissel’s tendency to breed in different locations among years (Figures 4 and 5). Despite the species’ declining population trend (see Population Status section), the number of blocks with breeding evidence doubled between Atlases. This is at least partially explained by the greater volunteer survey effort during the Second Atlas. It may also be a function of variations in the size of the Commonwealth’s breeding population among years, which has been documented as swelling every two to six years though immigration events (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

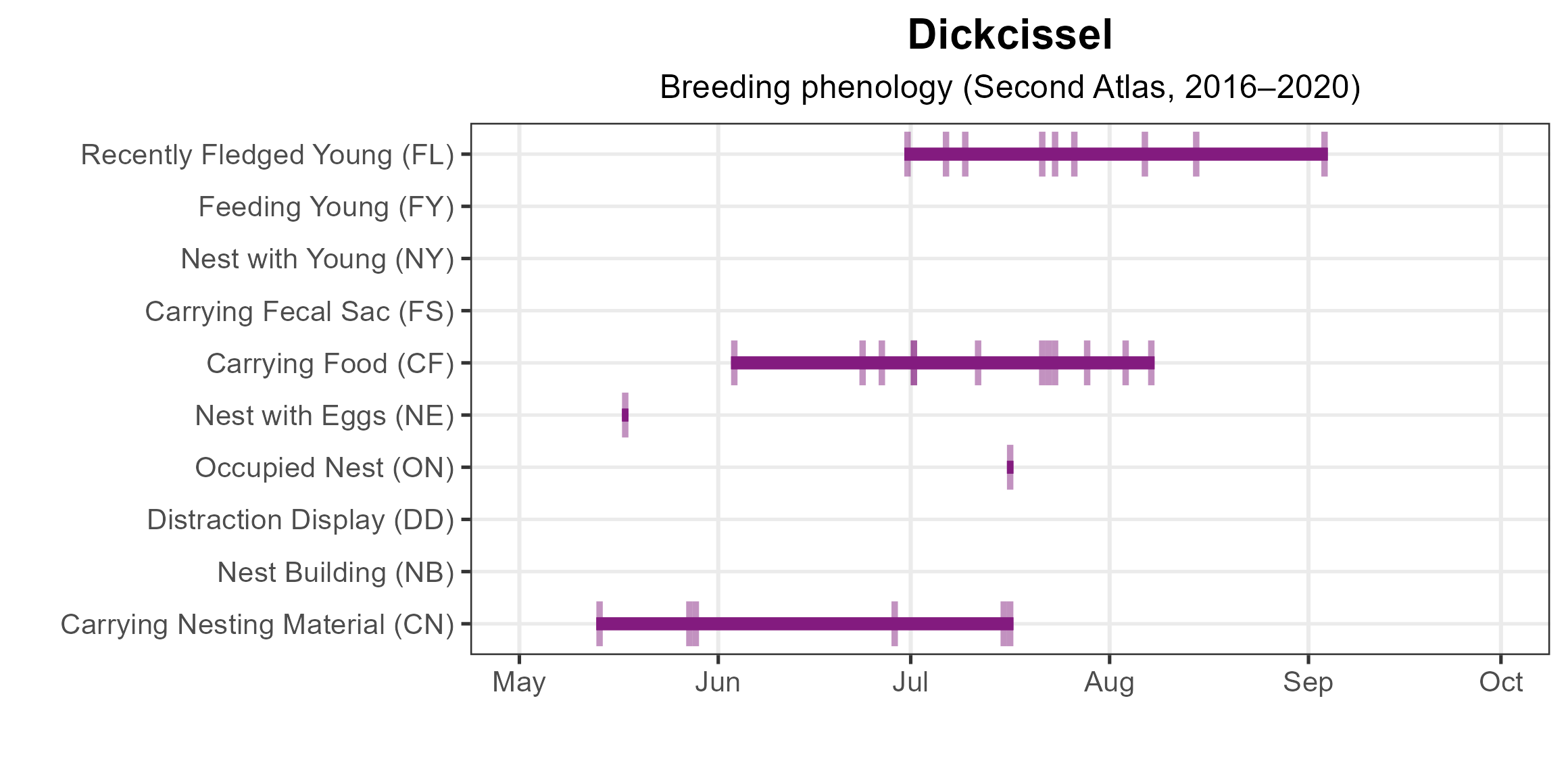

The earliest confirmation of breeding was of adults carrying nesting material in mid-May (Figure 6). However, most breeding confirmations throughout the season were obtained through observations of adults carrying food (June 3 – August 7) and of recently fledged young (June 30 – September 3).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Dickcissel breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Dickcissel breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Dickcissel phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Insufficient detections during Atlas point count surveys prevented the development of an abundance model for the Dickcissel. Similarly, this species is not consistently detected in Virginia by the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), which relies on roadside counts. Although the BBS does not provide credible population trend estimates for Virginia, within the Eastern BBS region, the Dickcissel experienced a significant 1.95% annual decline from 1966 to 2022. However, between Atlases (1987–2018), its population increased by a significant 1.42% per year (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 7).

Figure 7: Dickcissel population trend for the Eastern region as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Despite a positive trend for its Eastern population over the past 30 years, Dickcissel abundance is well below where it was when the BBS first launched in the mid-1960s. Based on this and on its small population size within the Commonwealth, the Dickcissel is classified as a Tier II Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Very High Conservation Need) in Virginia’s 2025 Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025).

Evaluating the status of the Dickcissel in Virginia is complicated by the species’ somewhat nomadic nature. Once a common breeder in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, the Dickcissel had retreated to its core breeding range in the Midwest and Great Plains by the end of the nineteenth century. Since then, its presence in the East has been sporadic and involved fewer birds (Sousa et al. 2020). Irregular movements into eastern states such as Virginia result in large fluctuations in Dickcissel distribution and numbers within the state (Sousa et al. 2020; Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). This phenomenon may be contributing to the fact that while the species is less likely to be found over a broad area of Virginia since the First Atlas, this decline appears scattered and patchy across the landscape. Variation in occurrence among years also prevents estimation of a population trend for the species in the Commonwealth.

Despite being well-outside of their core breeding range, Dickcissels are a well-established species within Virginia’s avian community and therefore worthy of conservation attention. From a conservation perspective, the Dickcissel is best treated as part of the broader grassland bird guild. These species share similar habitat-related threats on their breeding grounds and are declining faster than any other North American group (Rosenberg et al. 2019). Loss of their habitat to development, impacts to their productivity due to farming practices, and pesticide impacts to their prey base may all be contributing to their decline. Continued preservation of open private lands through easements and habitat maintenance through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Program and similar incentives can help mitigate development pressure. Targeted conservation efforts are being led by the Virginia Grassland Bird Initiative in the northern and northwestern parts of the state. The Initiative offers technical assistance and incentive programs to private landowners with working farms to promote good stewardship of pastures and hayfields and the birds that they support. Expansion of these efforts to other parts of the state would greatly enhance the reproductive success of Dickcissel and other species at a broader scale. Dickcissels may also be under threat on their wintering grounds in Venezuela, where they forage on agricultural crops and are subject to biological control programs. Further research is needed to determine whether this is having population-level impacts that should be addressed to benefit the breeding Dickcissel population.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rosenberg, K. V., Dokter, A.M., Blancher, P.J., Sauer, JR., Smith, AC., Smith, P.A., Stanton, J.C. PanJabi, A, Helft L., Parr, M., Marra, P.P. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366:120–124.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Sousa, B. F., S. A. Temple, and G. D. Basili (2022). Dickcissel (Spiza americana), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.dickci.02.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.