Introduction

The Dark-eyed Junco is a pleasant sparrow, most familiar to Virginians in winter. These “snowbirds” disappear in the breeding season except at high elevations. Additionally, the species primarily breeds in the north, with Virginia at the southern end of its range within the Appalachian Mountains.

In Virginia, there are two subspecies comprising the “slate-colored” division of the species: Junco hyemalis hyemalis, which winters and migrates throughout the state, and J. h. carolinensis, the breeding junco (also referred to as the “Carolina Junco”) of the Appalachian Mountains, which consists of some individuals that are residents and some that migrate short distances to lower elevations in winter (Hostetter 1961). Dark-eyed Juncos breeding in Virginia have blue-tinted ivory-colored bills compared to the pink bills of winter visitors (Nolan et al. 2020).

Dark-eyed Juncos also have the honor of being one of the best-studied species in Virginia, with generations of researchers studying their breeding, migration, and physiology at Mountain Lake Biological Station in Giles County.

Breeding Distribution

Dark-eyed Juncos breed solely in the Mountains and Valleys region and are most likely to occur along the Allegheny Mountains in Augusta, Bath, Highland, and Rockingham Counties; on Mount Rogers in Grayson and Smyth Counties; at Mountain Lake in Giles County; and along the Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 1). The species is likely absent from lower elevations.

The likelihood of Dark-eyed Juncos occurring in a block increases sharply with elevation, and it also slightly more likely to occur as forest cover increases. As an Appalachian breeder, the species is known to prefer habitats at higher elevations, and it typically breeds above 3,000 ft (914 m) in elevation (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). More specifically, Dark-eyed Juncos were found at both the lowest (3,840 ft (1170 m)) and highest (5,740 ft (1750 m)) elevations sampled in surveys of high-elevation habitat in western Virginia (Lessig 2008). Dark-eyed Juncos are slightly less likely to be found in blocks with greater cover of evergreen shrubs, which could include rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.) and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia).

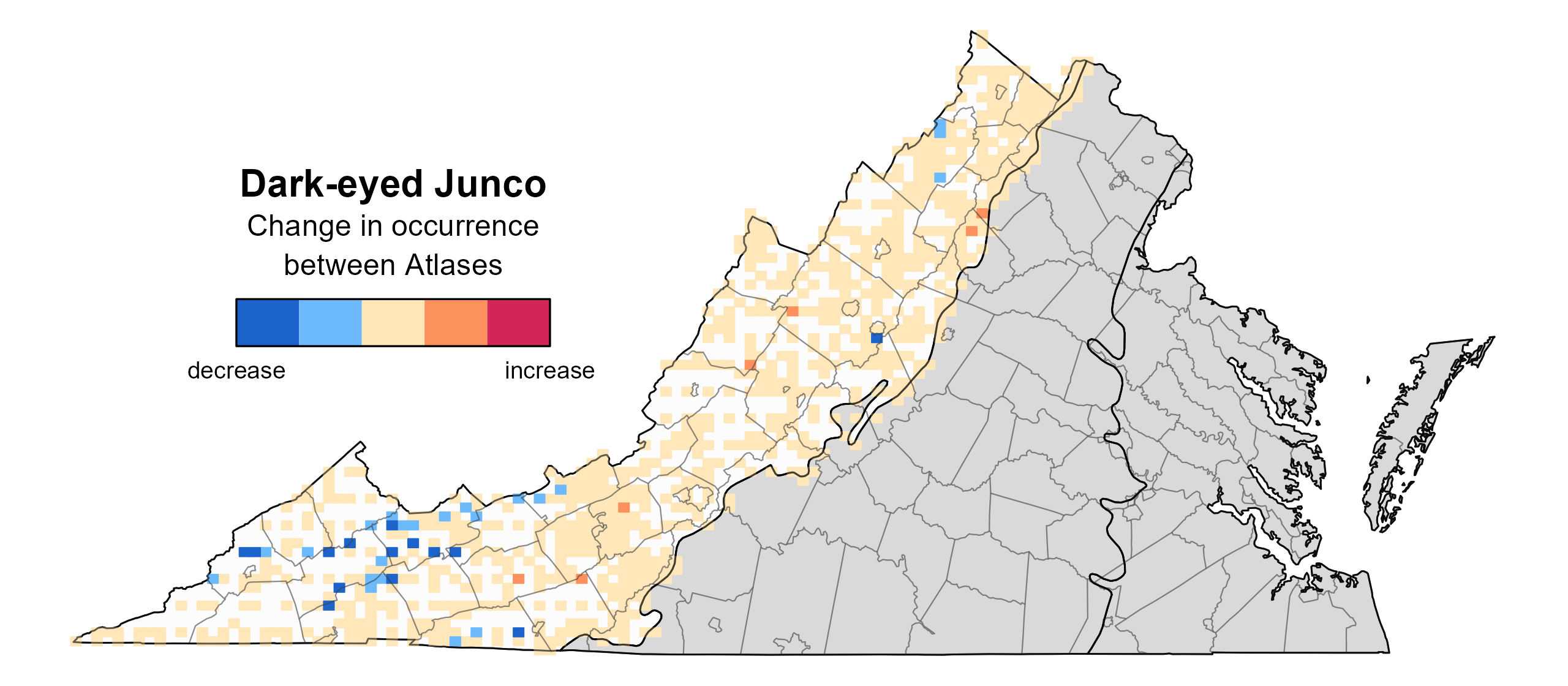

In keeping with its positive population trend (see Population Status), the Dark-eyed Junco’s likelihood of occurring between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2) remained relatively constant throughout the Mountains and Valleys region except in the southwestern portion (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Dark-eyed Junco breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

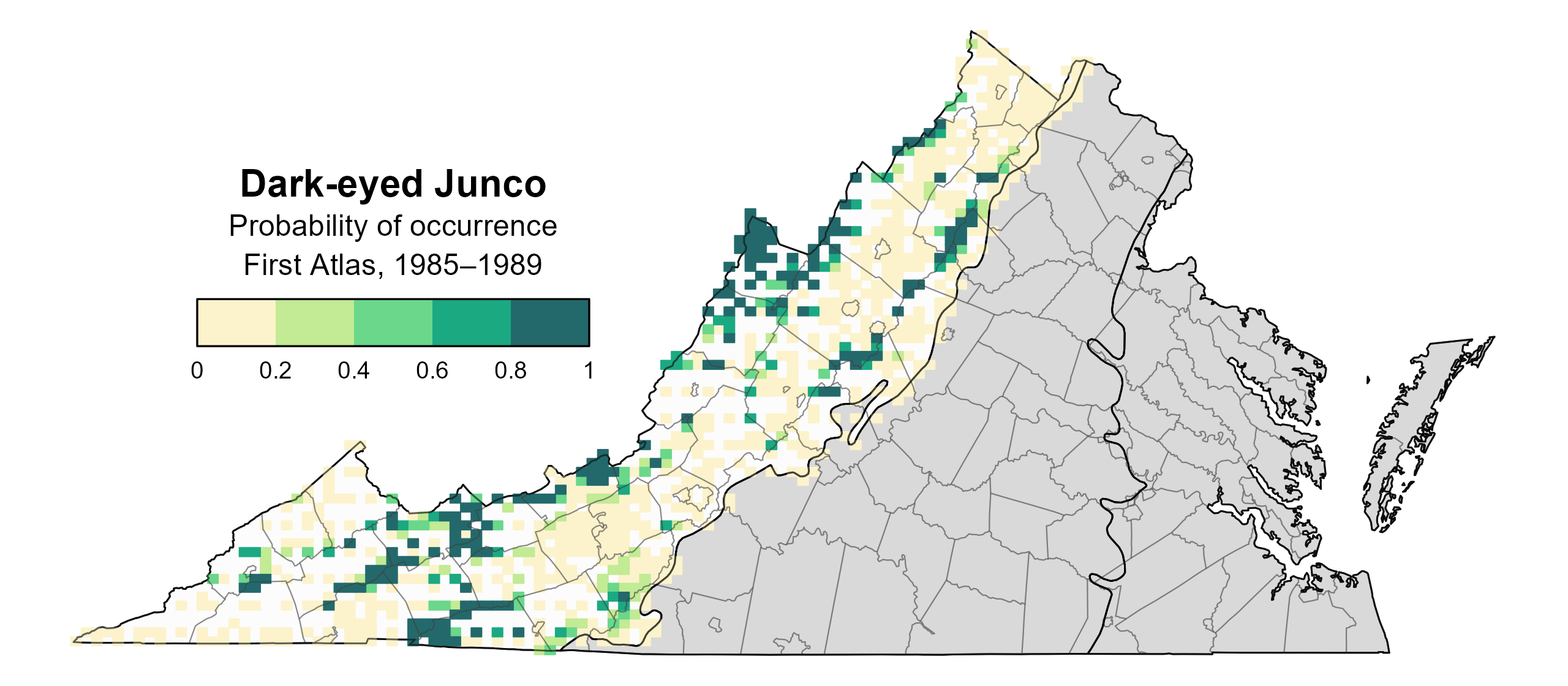

Figure 2: Dark-eyed Junco breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Dark-eyed Junco change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

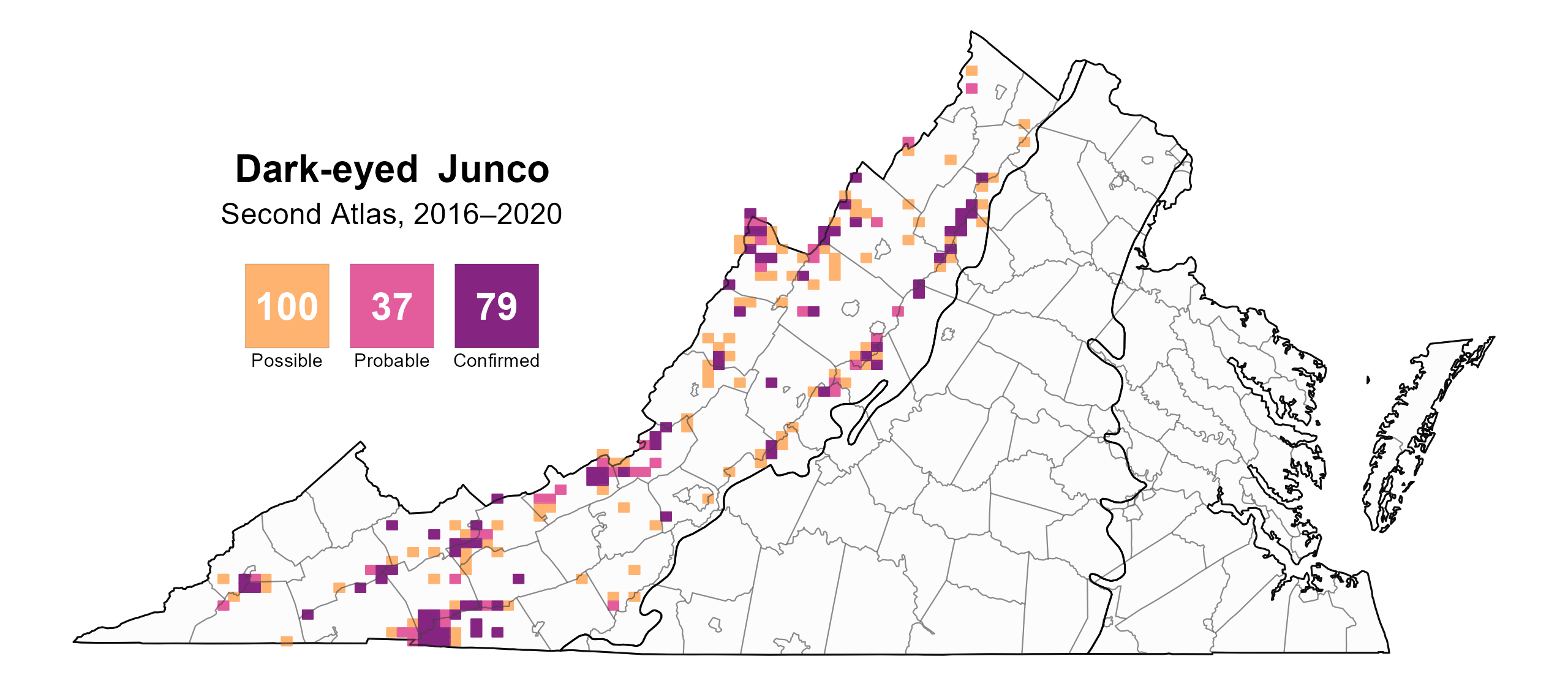

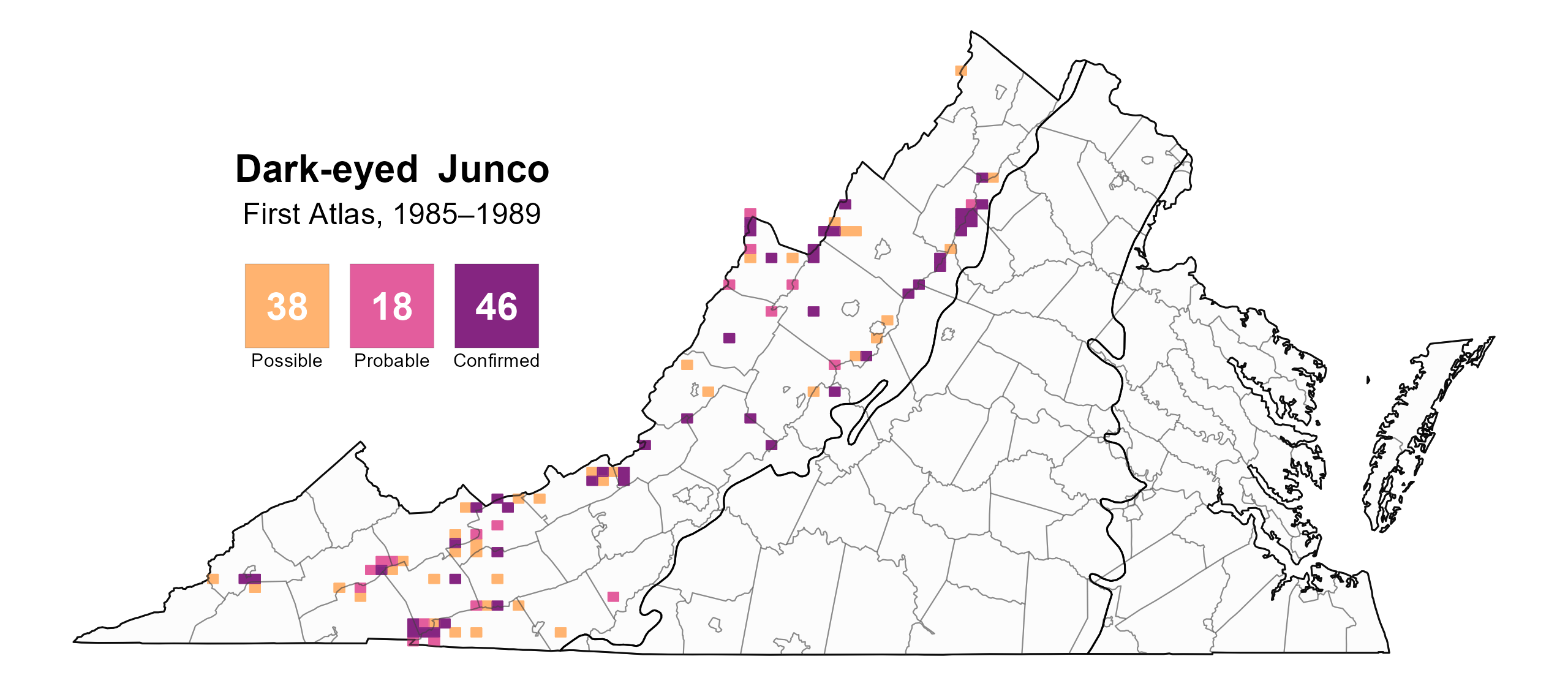

Dark-eyed Juncos were confirmed breeders in 79 blocks and 28 counties and probable breeders in an additional three counties (Figure 4). Confirmations followed elevational lines, with birds breeding along the crests of the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains. Hotspots of confirmations occurred around Mount Rogers (Grayson and Smyth Counties) and around Mountain Lake (Giles County), where the species has been studied extensively. The pattern of breeding observations was similar between the First Atlas and the Second Atlas, although more observations were recorded during the Second Atlas, which may have been due to the increase in survey effort (Figure 5).

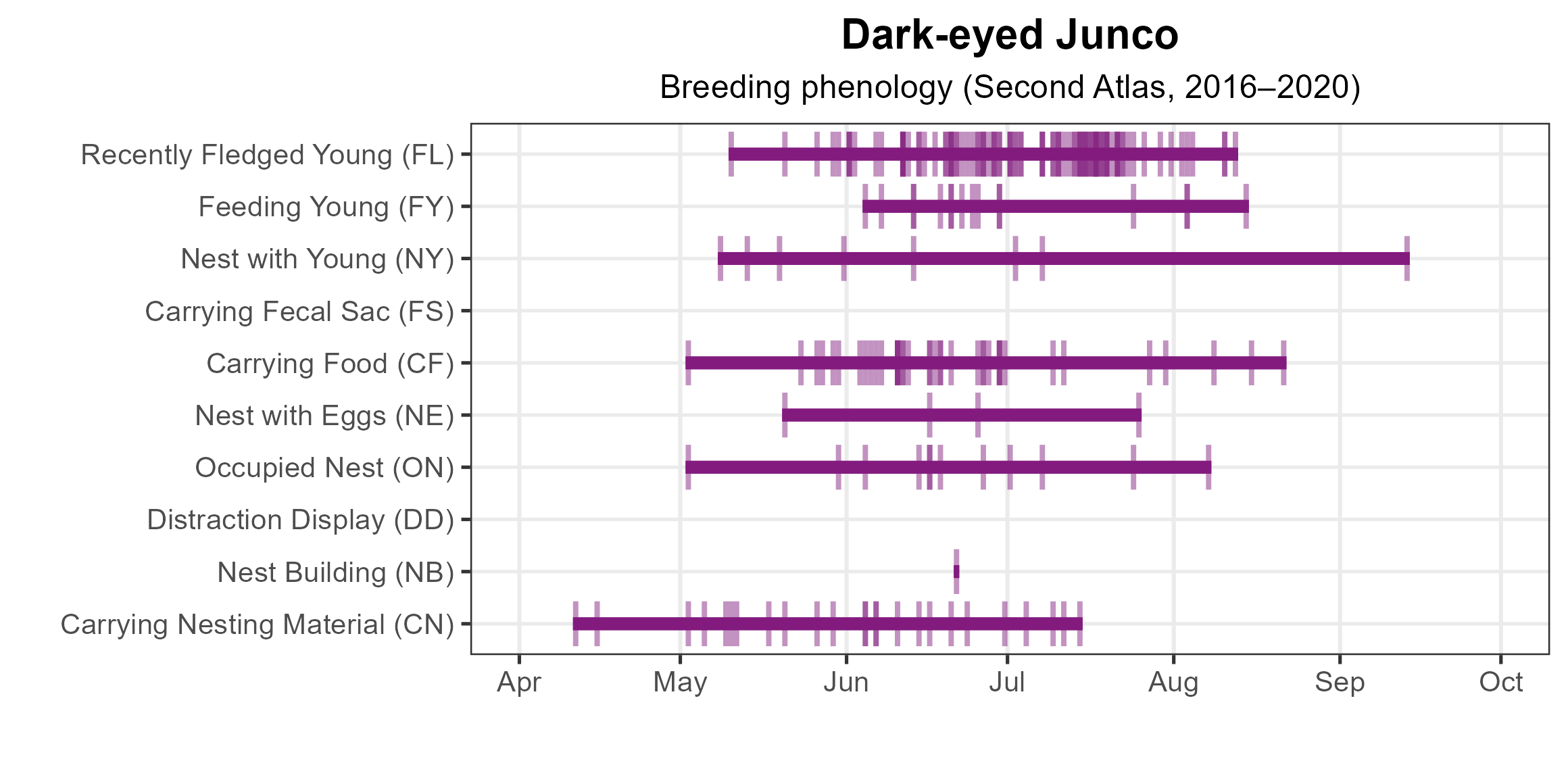

As a well-studied, ground-nesting species, observers found more Dark-eyed Junco nests than nests of many other passerines. Their nests are easy to find, making them vulnerable to predators; research at Mountain Lake Biological Station has found that approximately 50% of nests are consumed by predators, primarily by eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) and deer mice (Peromyscus spp.) (Nolan et al. 2020). The resident nature of many carolinensis juncos allows for a long breeding season, albeit one that is limited by suitable weather at elevation. Breeding was confirmed from February 16 (nest building) through September 13 (nest with young) (Figure 6).

For more general information on the breeding habits of the Dark-eyed Junco, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Dark-eyed Junco breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Dark-eyed Junco breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Dark-eyed Junco phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

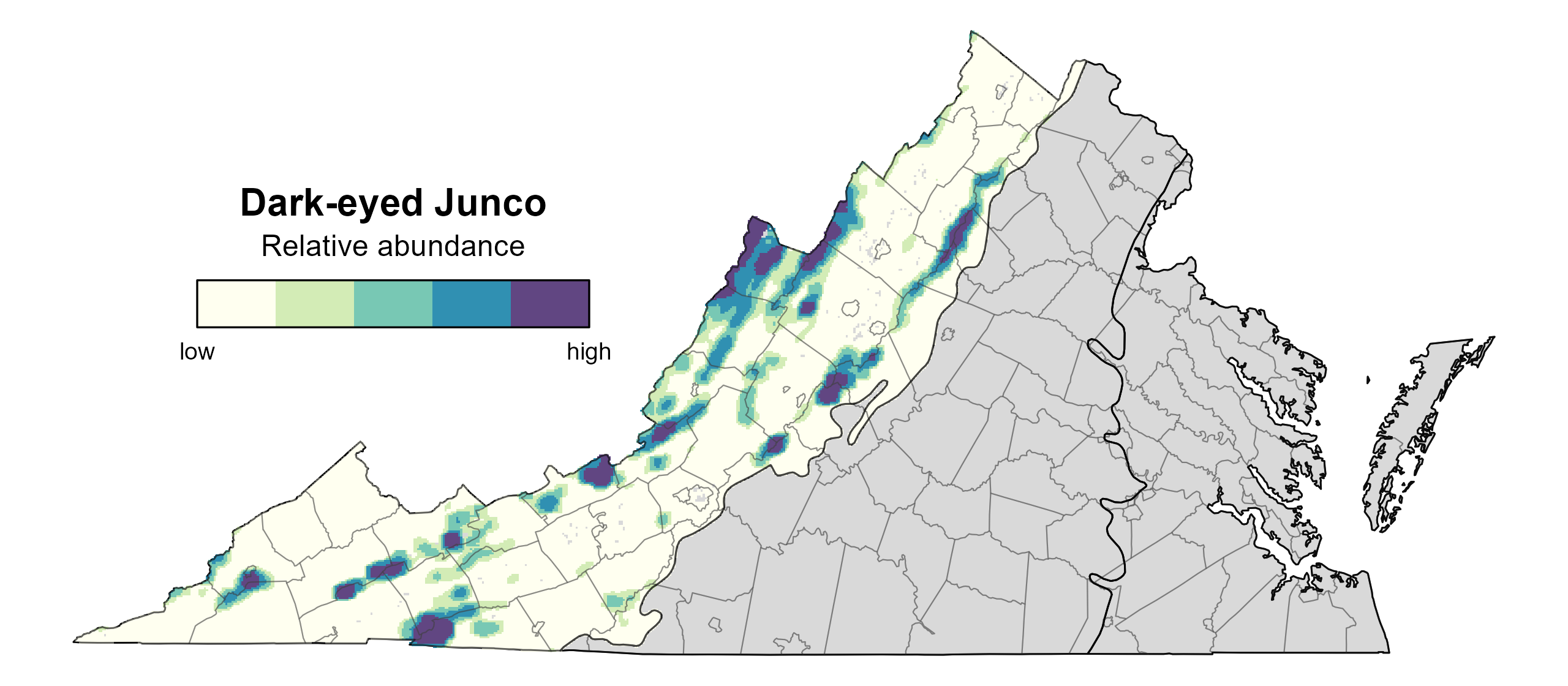

Dark-eyed Junco relative abundance was estimated to be highest on mountain peaks, particularly at Mount Rogers and other higher-elevation sites (Figure 7). The species was predicted to be less abundant at lower elevations.

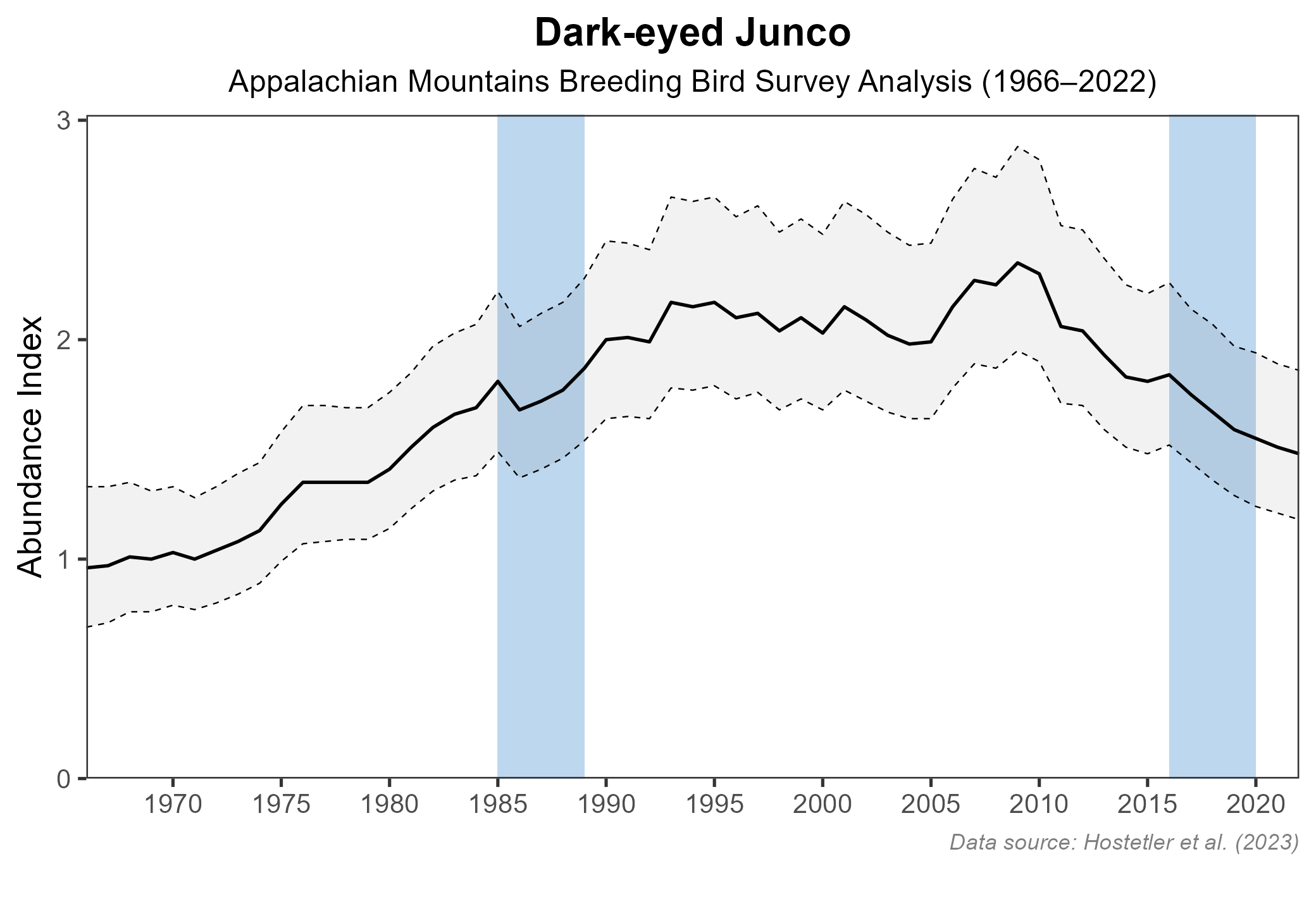

The total estimated Dark-eyed Junco population in the state is 76,000 individuals (with a range between 41,000 and 144,000). North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trends for the Dark-eyed Junco were not credible for Virginia, where the species was only detected along five routes. The BBS trend for the broader Appalachian Mountains region showed a significant increase of 0.78% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between Atlases, the BBS trend showed a nonsignificant decline of 0.1% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Dark-eyed Junco relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high. Areas in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 8: Dark-eyed Junco population trend for the Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

While Dark-eyed Juncos are abundant and widespread in Virginia during the winter months, the carolinensis subspecies that breeds in Virginia has a more restricted range. Within that range, however, it is fairly widespread and abundant, having been found at all 36 sites included in breeding bird surveys of high-elevation forests in the Commonwealth and having been the third most frequently detected species in those surveys (Lessig 2008). Although they have an affinity for high-elevation sites, Dark-eyed Juncos are considered high-elevation generalists that are adapted to multiple habitat types and habitat characteristics (Lessig 2008), including both hardwood and coniferous forests (Nolan et al. 2020). As such, they are less likely to be impacted by habitat disturbance and may be less vulnerable to the effects of climate change, which otherwise threatens high-elevation forests.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Hostetter, D. (1961). Life history of the Carolina Junco, Junco hyemalis carolinensis Brewster. The Raven 32:97–170.

Lessig, H. (2008). Species distribution and richness patterns of bird communities in the high elevation forests of Virginia. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Nolan, V, Jr., E. D. Ketterson, D. A. Cristol, C. M. Rogers, E. D. Clotfelter, R. C. Titus, S. J. Schoech, and E. Snajdr (2020). Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.daejun.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) 2007. Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.