Introduction

In Virginia and throughout their range, Cooper’s Hawk and Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus) are often confused, with good reason. Their plumage is nearly identical, and they are similar in size. To distinguish the Cooper’s Hawk, its tail appears round, and it has a dark, almost black crown. Additionally, in flight, the head of the Cooper’s Hawk projects in front of the plane of the wing (Rosenfield et al. 2020).

Cooper’s Hawks are very aggressive when pursuing prey, sometimes hurtling through brush or chasing small mammals on foot. One study found that 23% of Cooper’s Hawk skeletons showed that their chest bones had healed-over fractures (Roth et al. 2002).

Breeding Distribution

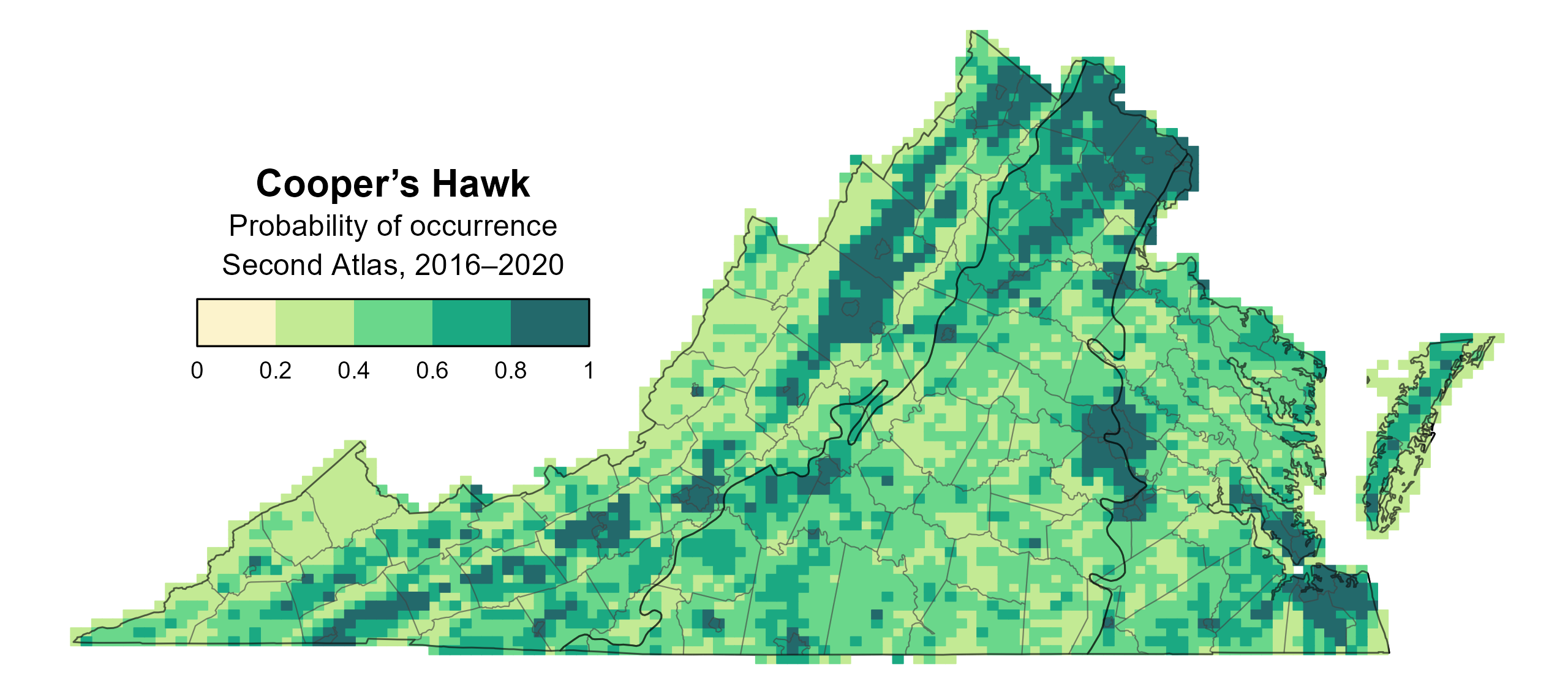

While Cooper’s Hawks occur throughout Virginia, their distribution is patchy, with the highest likelihood of occurring in valleys with both forest and farmland, such as those in Augusta, Frederick, and Rockingham Counties, and near urban-suburban areas, such as Richmond, Norfolk, and Northern Virginia (Figure 1). This pattern of habitat use (agricultural and developed lands) is consistent with behavior throughout the species’ range. Once considered to be birds of the forest, Cooper’s Hawks have readily adapted to urban environments, where they capitalize on abundant populations of Rock Pigeons (Columba livia) and Mourning Doves (Zenaida macroura) (Rosenfield et al. 2020).

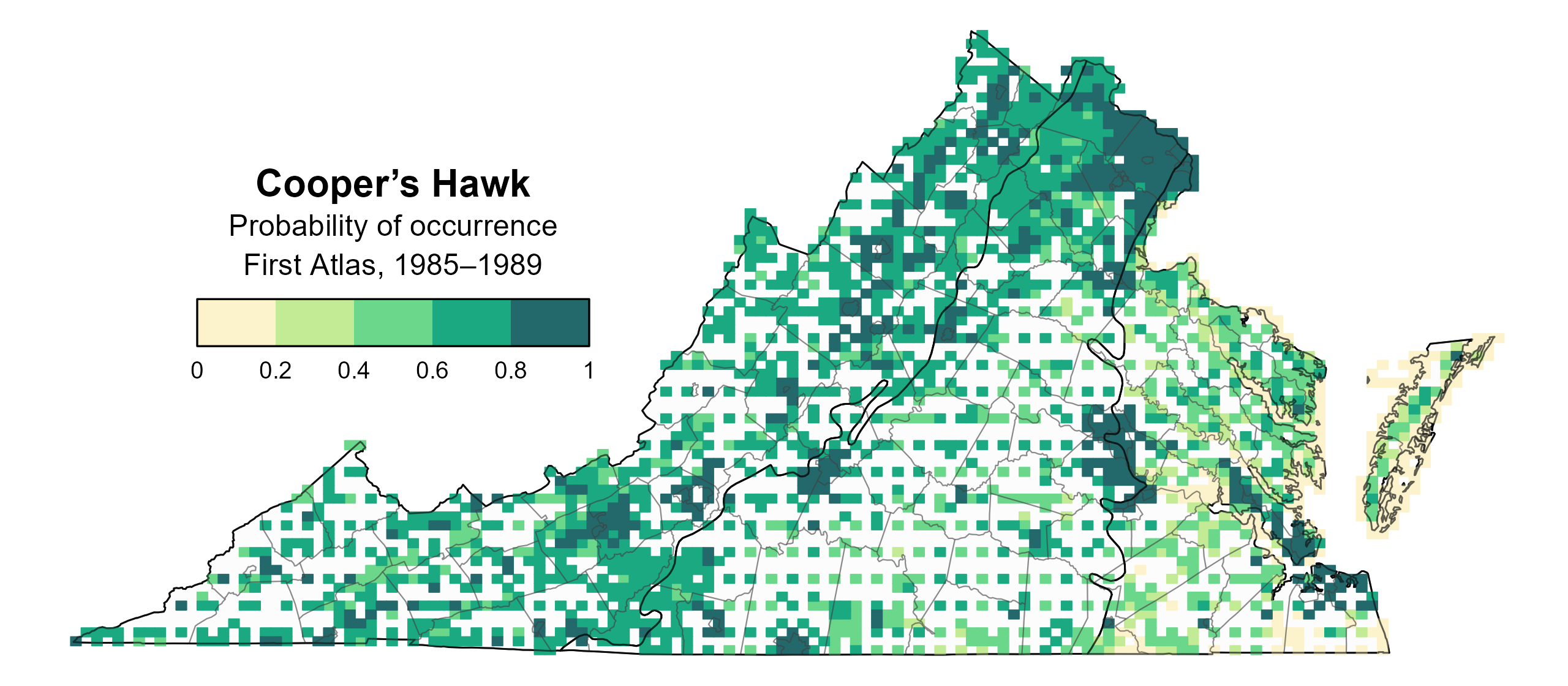

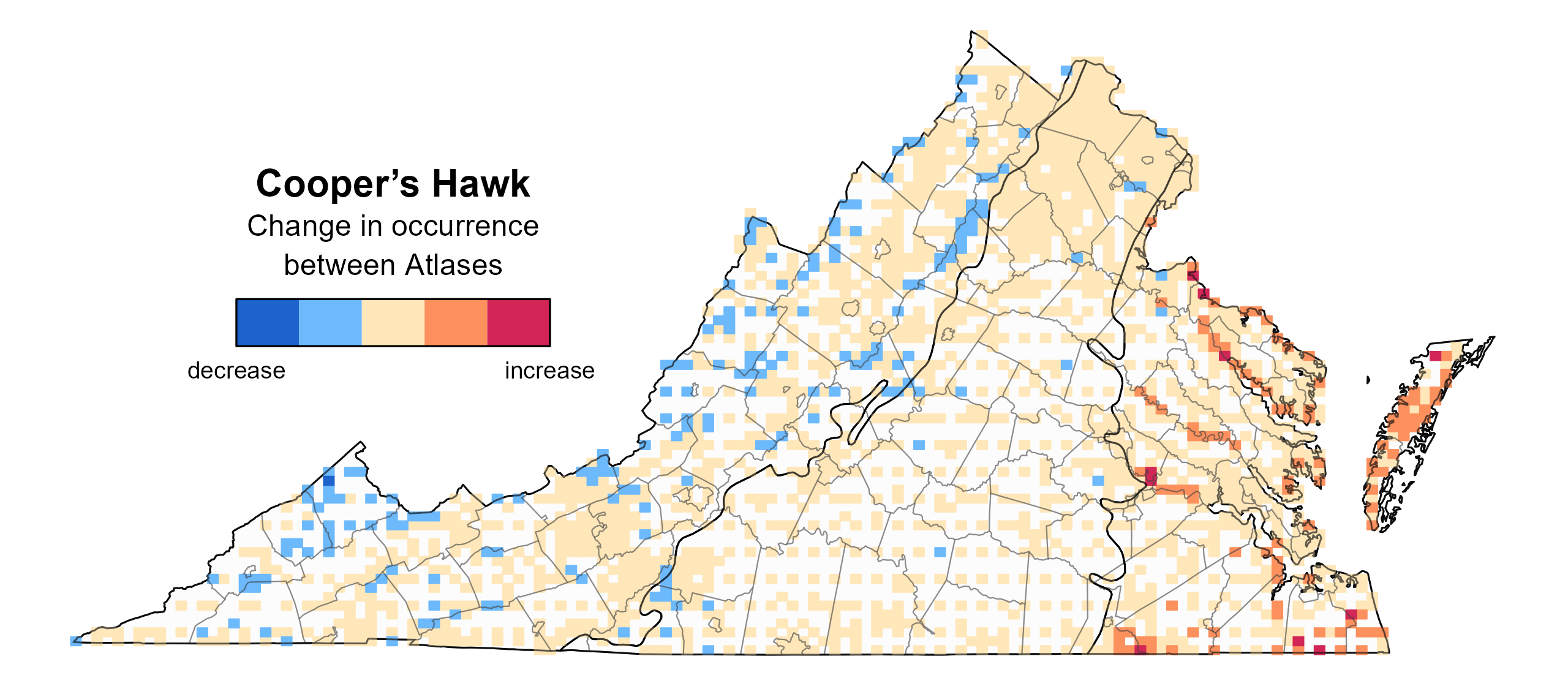

Cooper Hawk’s occurrence between the First and Second Atlases decreased across most of the Mountains and Valleys region, remained mostly constant in the Piedmont region, and increased in the Coastal Plain region along major rivers, around developed areas, and on the Eastern Shore (Figures 1 to 3). A more careful examination reveals that the change most likely represents a shift from heavily forested areas in the Mountains and Valleys region to urban and suburban and agricultural environments in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions.

Figure 1: Cooper’s Hawk breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks).

Figure 2: Cooper’s Hawk breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Cooper’s Hawk change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

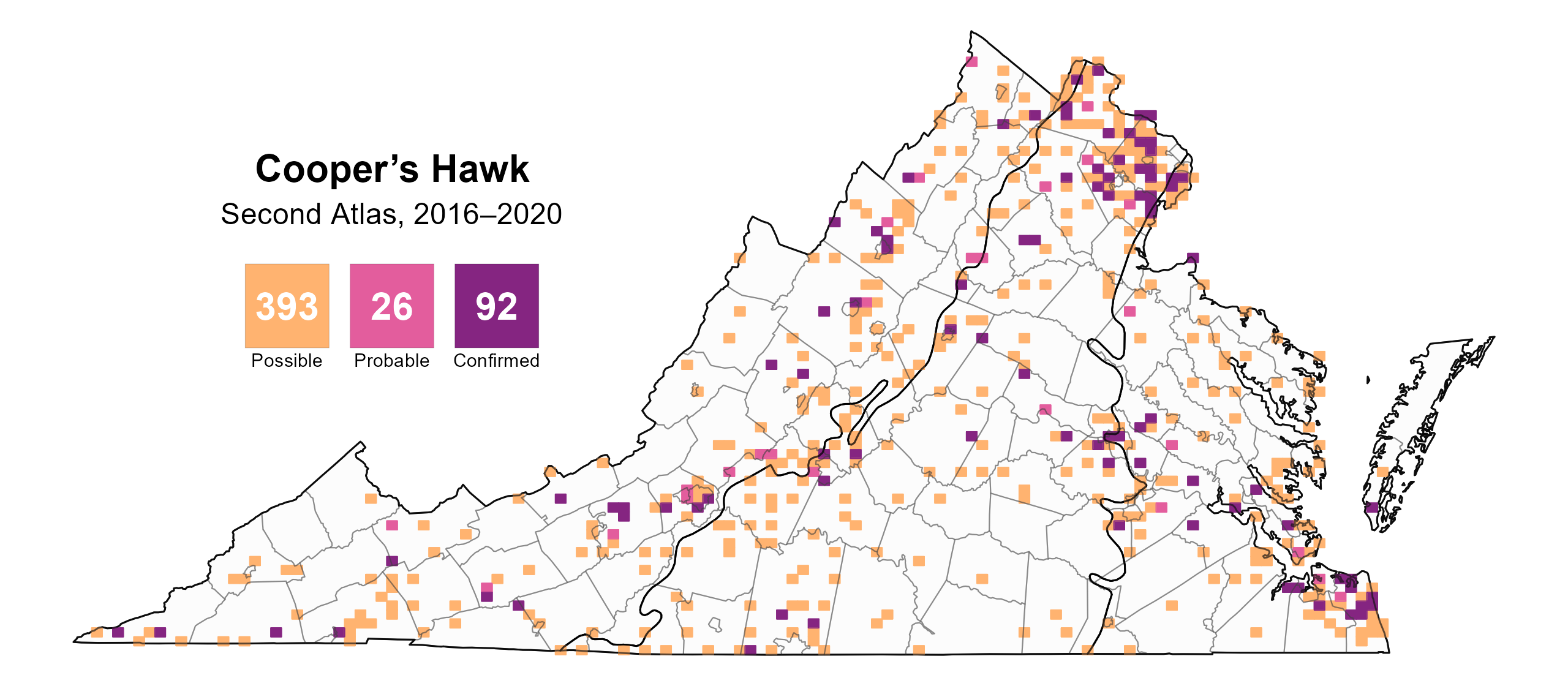

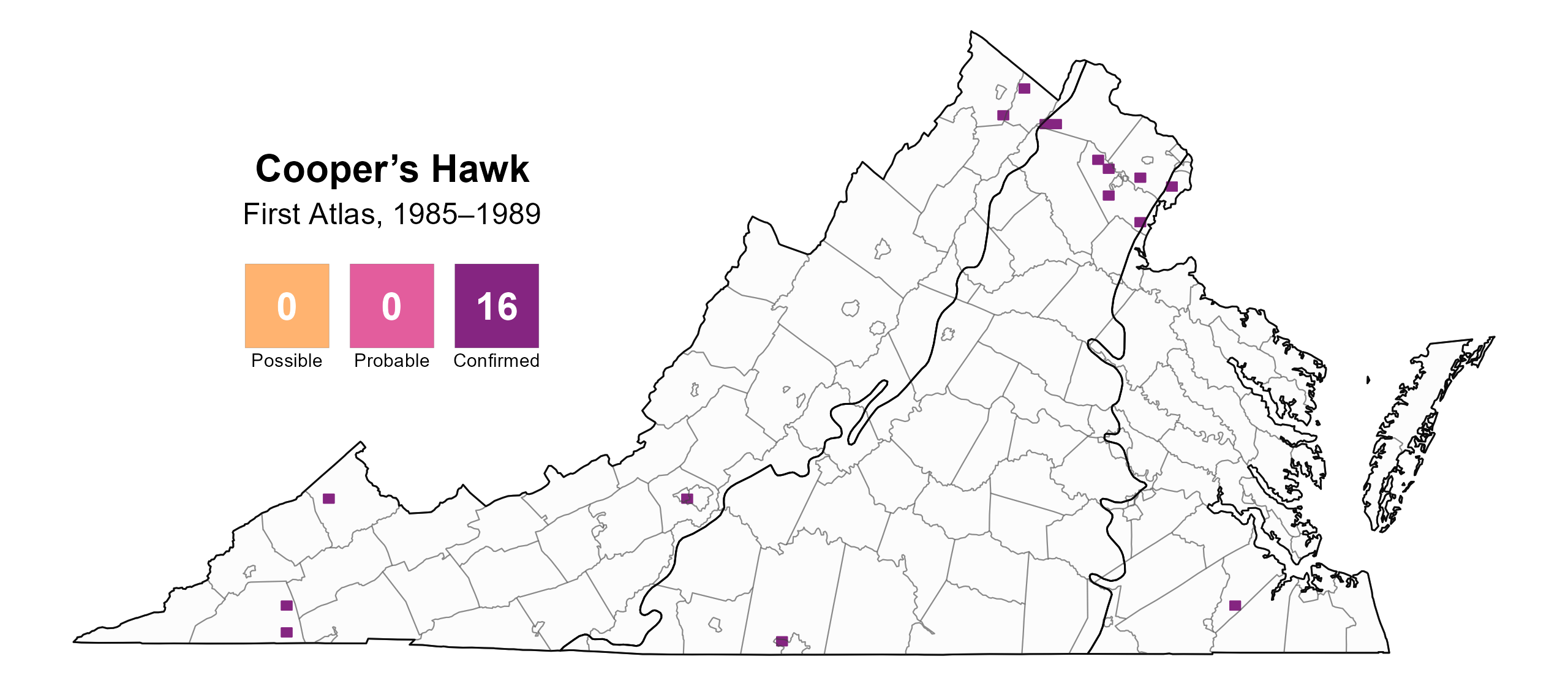

Cooper’s Hawks were confirmed breeders in 92 blocks and 48 counties, and they were found to be probable breeders in nine additional counties (Figure 4). They were observed breeding at substantially more locations during the Second Atlas than during the First Atlas, indicative of its population increasing across the state (see Population Status section). However, it is important to note that survey effort was considerably less during the First Atlas (Figure 5).

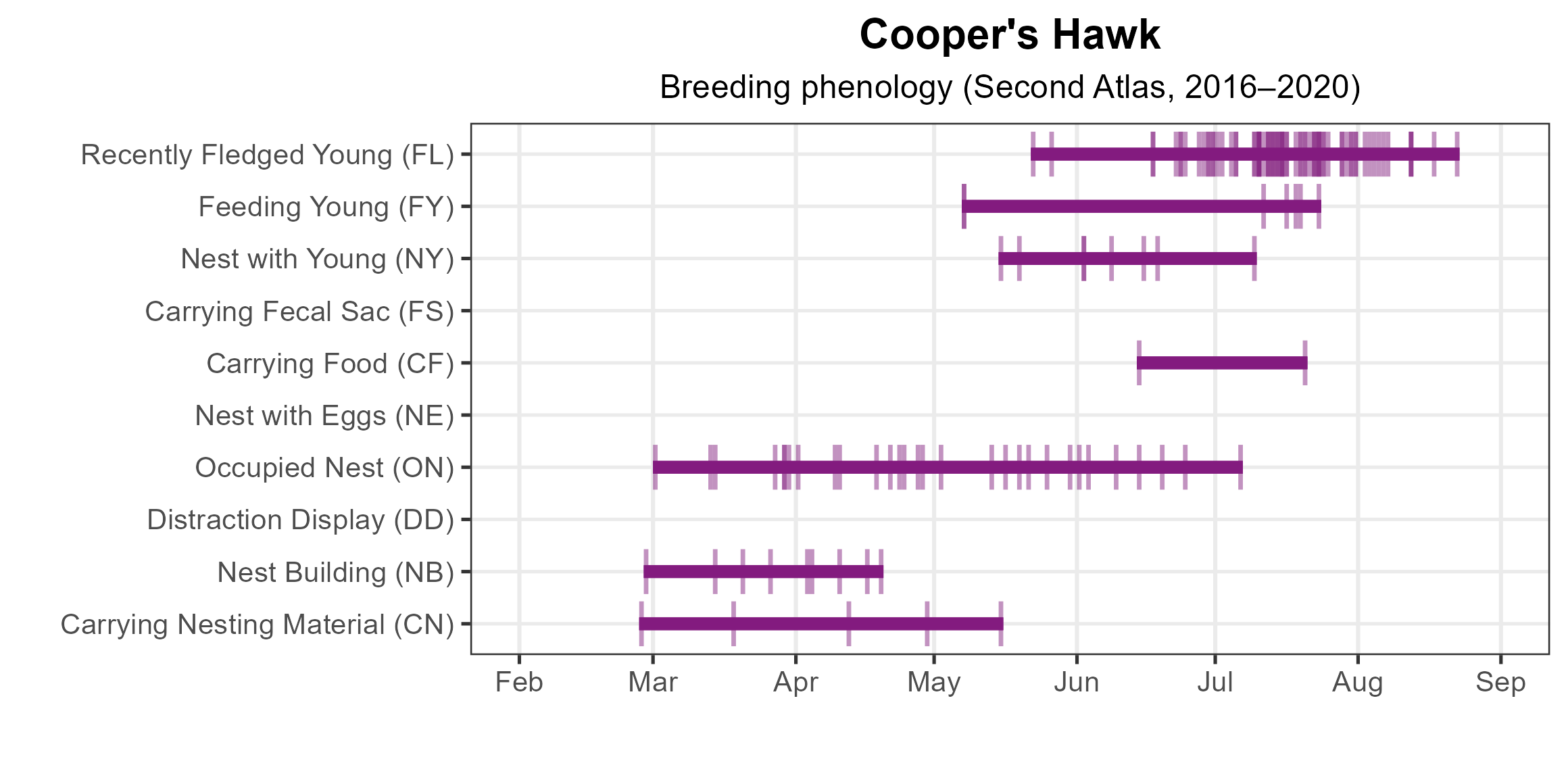

Volunteers observed occupied nests from March 1 through early July and recently fledged young were seen from late May through late August (Figure 6). Breeding was primarily confirmed through observations of recently fledged young, occupied nests, and adults carrying food. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Cooper’s Hawk, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Cooper’s Hawk breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Cooper’s Hawk breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Cooper’s Hawk phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

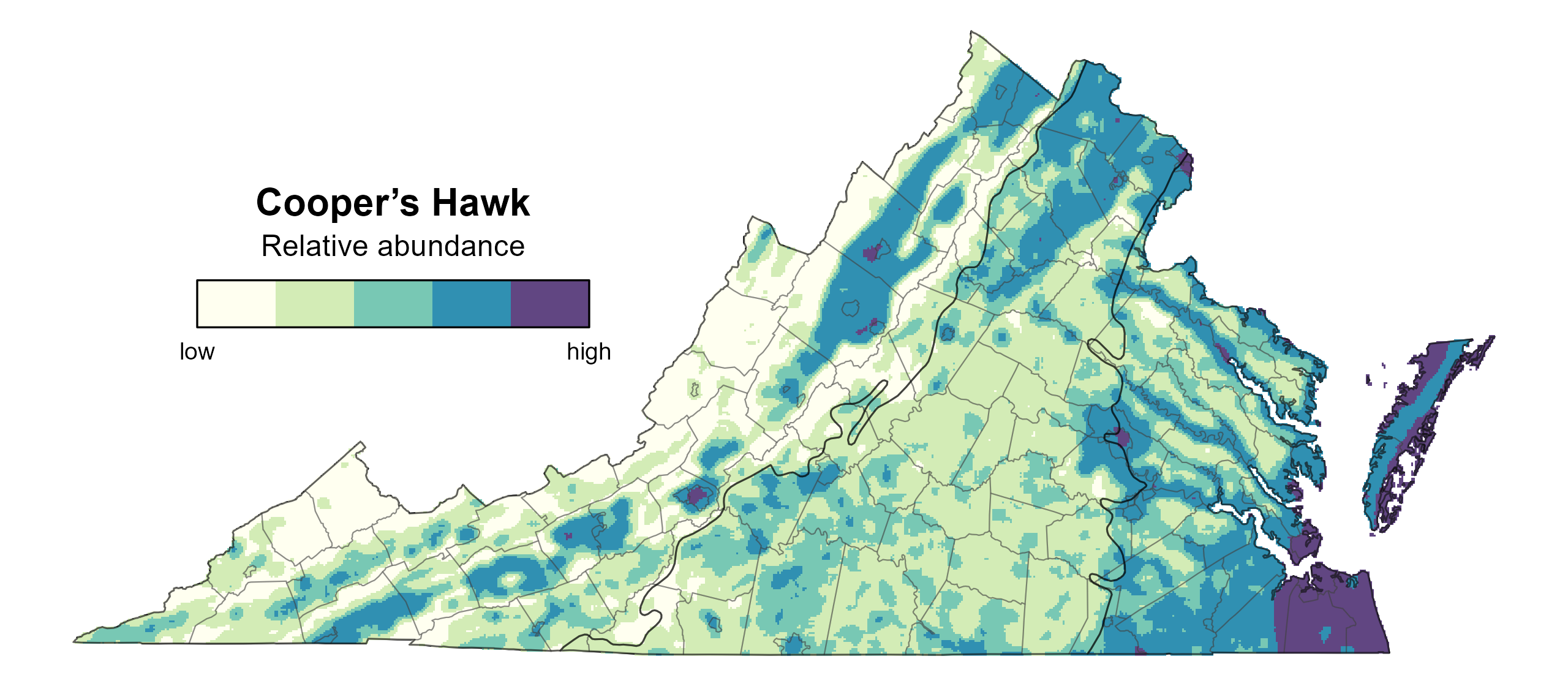

Cooper’s Hawk relative abundance was estimated to be highest in the Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach area and the Eastern Shore but also high in the same rural valleys and other urban-suburban centers that supported higher likelihood of occurrence values (Figure 7).

The total estimated Cooper’s Hawk population in the state is approximately 36,000 detectable individuals (with a range between 5,000 and 254,000). The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) population data for Cooper’s Hawk in Virginia and regionally do not produce credible trends; thus, they are not reported here. However, although Cooper’s Hawk experienced population declines from the 1940s to early 1960s, their numbers have increased substantially (5- to 6-fold increase) since that time (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

Figure 7: Cooper’s Hawk relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high.

Conservation

With an increasing population trend in the state and throughout its range (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; Rosenfield et al. 2020), Cooper’s Hawk is not considered a species of conservation concern in Virginia. However, as Cooper’s Hawks shift their habitats from forest to urban-suburban landscapes, it is likely that new conservation challenges will arise in coming decades. For example, collisions with cars and buildings have increased in recent years, and an Arizona study found that nestlings suffered from parasite infections acquired from a steady diet of city-dwelling Rock Pigeons (Rosenfield et al. 2020).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Rosenfield, R. N., K. K. Madden, J. Bielefeldt, and O. E. Curtis (2020). Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), Version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.coohaw.01.

Roth, A. J., G. S. Jones, and T. W. French (2002). Incidence of naturally-healed fractures in the pectoral bones of North American Accipiters. Journal of Raptor Research 36. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/jrr/vol36/iss3/14.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.