Introduction

Alongside the Royal Tern (Thalasseus maximus), the Common Tern is characteristic of Virginia beaches in summer. Its bounding flights offshore accompanied by barked keeyur calls are followed by a dramatic plunge into the surf. It is a common summer resident on the coast and in the Chesapeake Bay, rarely encountered inland as a migrant (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). It is a colonial nester, residing in large, noisy colonies alongside Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger), Gull-billed Terns (Gelochelidon nilotica), and other species.

Historically, Common Terns have been a fixture among Virginia’s barrier island nesting avifauna since at least 1875 (Bailey 1876). Like many of the other species, Common Terns were hunted to very low numbers by the turn of the 20th century for the millinery trade, but they soon began to recover after they were protected by legislation. Nesting began on the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT) in 1977 (Kain 1985), shortly after the second portion of the HRBT was completed. Despite these recoveries, in recent years, the species has declined and faces a precarious future in the Commonwealth.

Breeding Distribution

The Common Tern was well-covered during the Second Atlas by the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey, a coastal census conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in collaboration with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) and The Nature Conservancy. The survey identifies nesting locations of this and other species that breed in colonies. Because the Common Tern only breeds within the survey area, there was no need to model its distribution. For information on where the species occurs in Virginia’s Coastal Plain, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Given the breeding biology of the species, Common Terns are unlikely to have nested in blocks without confirmed breeding evidence (see Interpreting Species Accounts). Confirmation of breeding was based on records generated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey in 2018. Additional breeding confirmations were reported by Atlas volunteers in other years of the Second Atlas period.

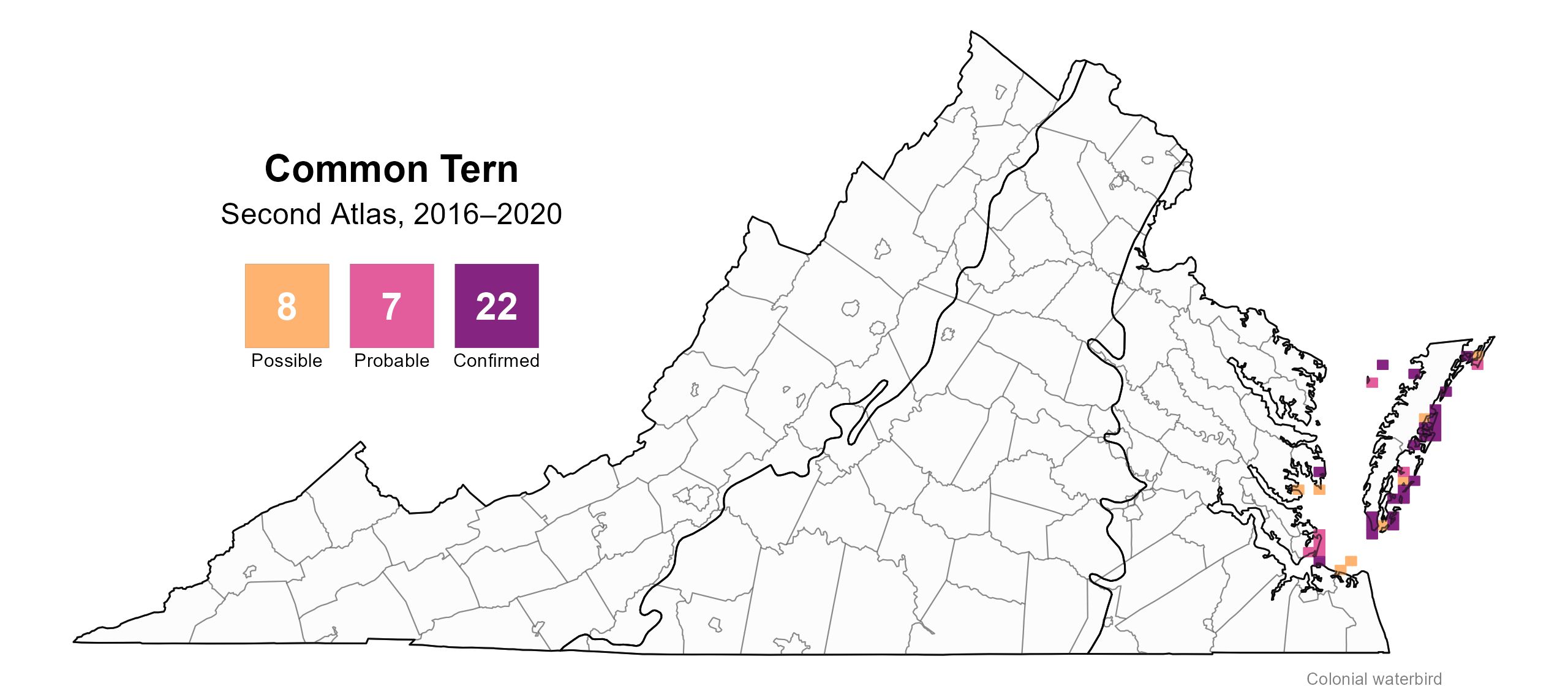

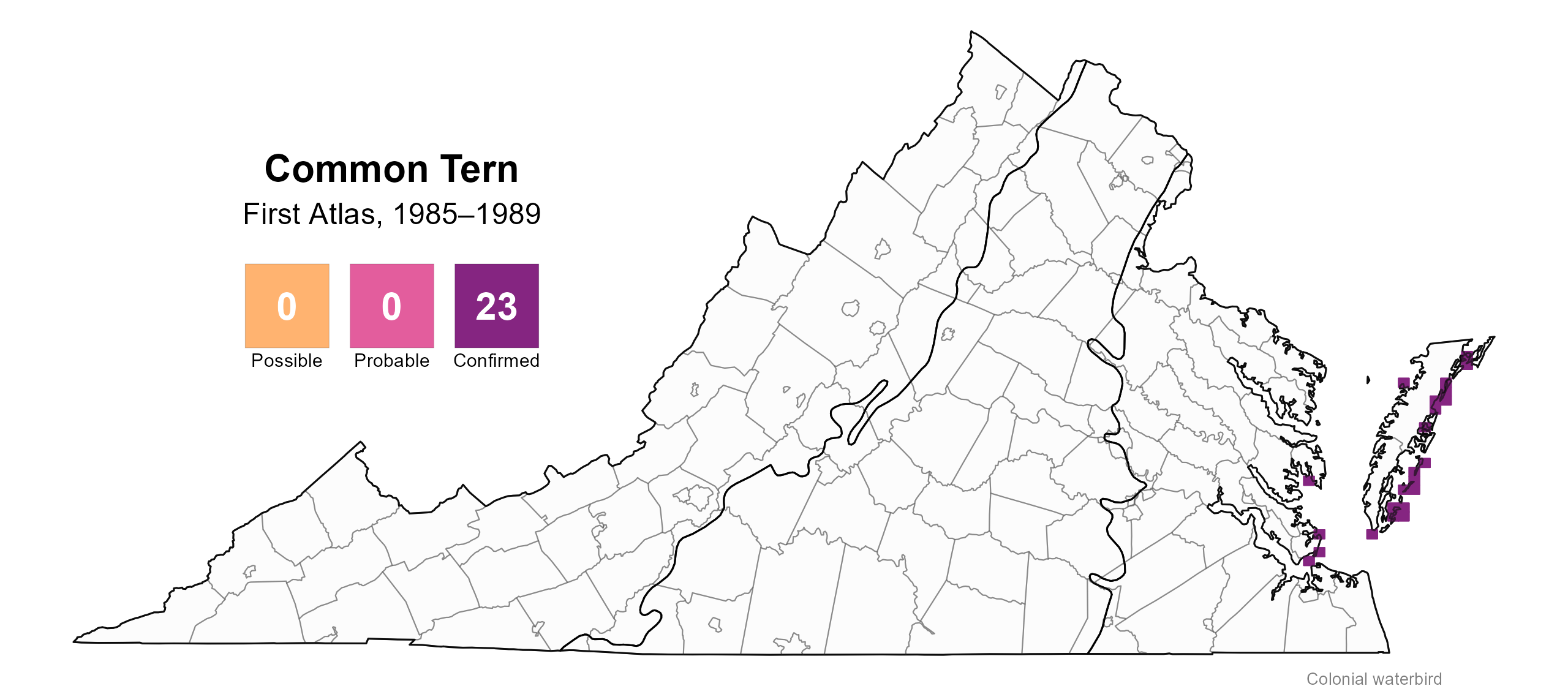

Common Terns were confirmed breeders on the seaside of the Eastern Shore, islands in the Chesapeake Bay, and around the HRBT (Figure 1). Breeding was confirmed in 22 blocks in three counties (Accomack, Mathews, and Northampton) and two cities (Hampton and Norfolk). The number of confirmed blocks during the Second Atlas decreased from those during the First Atlas, where it was confirmed in 23 blocks (Figure 2). Since the First Atlas, Common Terns have disappeared from the western Chesapeake Bay and lower tidewater area outside of the HRBT (Watts et al. 2024).

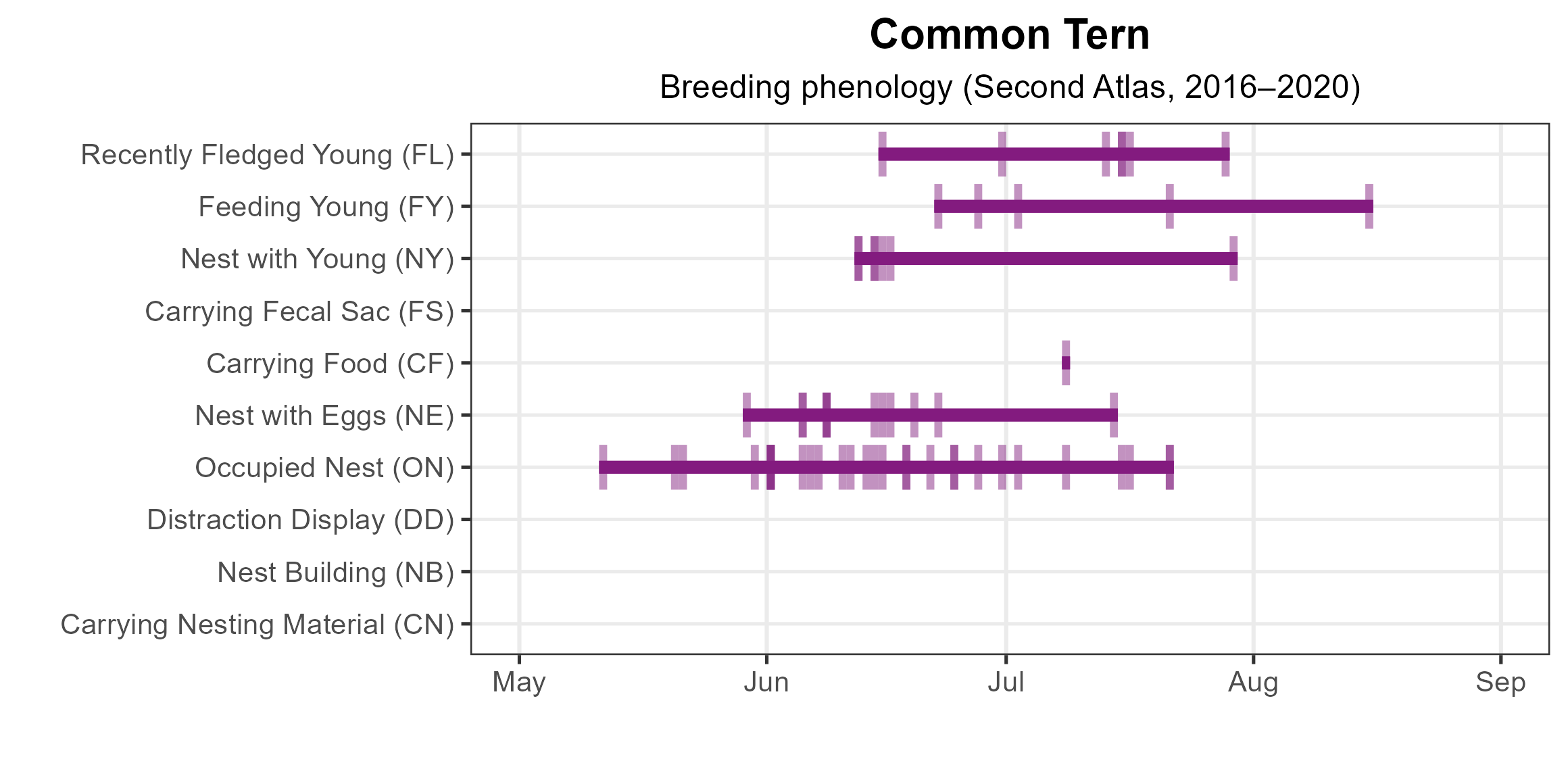

Common Terns were observed on nests from May 11 to July 21. Nests had eggs from May 29 to July 14, and young from June 12 to July 29 (Figure 3). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Common Tern, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Common Tern breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the level of breeding evidence observed. Nesting is unlikely outside of confirmed blocks.

Figure 2: Common Tern breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the level of breeding evidence observed.

Figure 3: Common Tern phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Because the Common Tern was not detected on Atlas point count surveys, an abundance model could not be developed. However, the distribution and size of Common Tern colonies derived from the 2018 Virginia Colonial Waterbird survey are displayed on the CCB Mapping Portal.

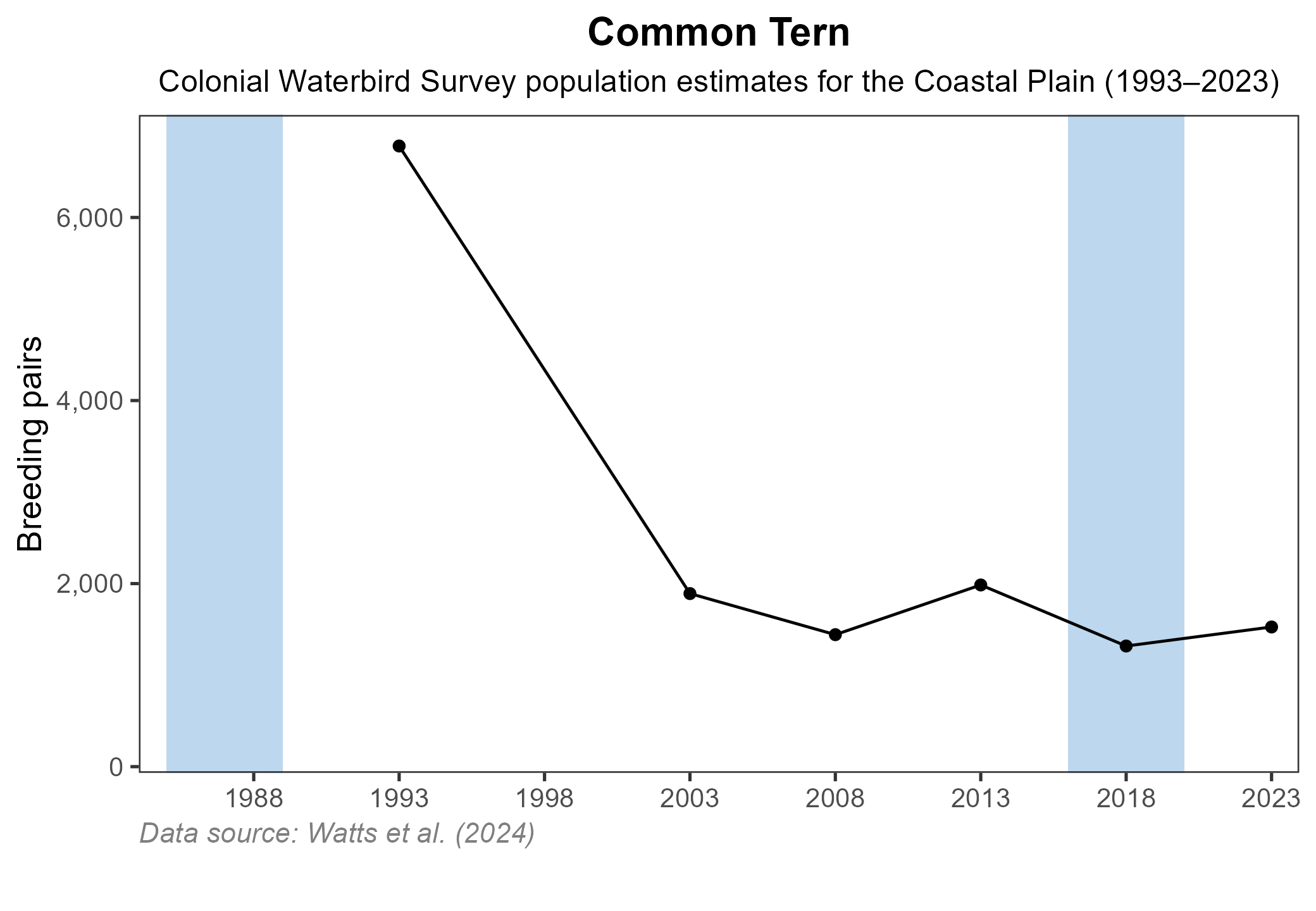

Data sources point to long-term declines in the Common Tern. Although the distribution of their breeding colonies remained constant during the First Atlas period, the number of adults declined 40% from 1984–1989 (Williams et al. 1990). These changes were attributed to moving population centers, including birds moving to the recently colonized HRBT (Williams et al. 1990). The growth of this colony provided little compensation for the species consistent decline elsewhere, particularly on the barrier islands. The Virginia Colonial Waterbird Surveys recorded a decline in the number of breeding pairs from 6,781 in 1993 to a low of 1,318 in 2018, rising slightly to 1,526 in 2023 (Watts et al. 2019, 2024; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Common Tern population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by the Virginia Colonial Waterbird Survey (Watts et al. 2024). A data point is not included for 1998, as the Survey covered a smaller geographic area in that year. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Common Tern is classified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Tier II: Very High Conservation Need) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025). As a colonial-nesting species, its populations are vulnerable to human disturbance, predation, and loss of nesting sites. The location of the large nesting colony on the HRBT made vehicle collisions a major source of chick mortality. In addition to cars, chicks are at risk of avian and mammalian predators. Predation by gulls has been identified as a major cause of nest failure for Common Terns (Arnold et al. 2020).

Breeding habitat can be lost to rising sea levels, storm inundation, or human activity. The major nesting colony containing Common Terns was recently displaced when the Virginia Department of Transportation began a project to expand the HRBT. In 2020, the South Island HRBT expansion project paved over the former colony site. The VDWR and partners were able to provide alternative habitat on the historic Fort Wool (also known as Rip Raps Island) and floating barges, which now provide replacement habitat for multiple nesting seabird species, including Common Tern (Sweeney et al. 2024).

One advantage of this new site is that it is close to the old breeding site. This should minimize the distance needed to travel between known foraging sites and the nesting colony, which is a major energy expenditure for these birds– they spend 20% of their time transiting from the colony to foraging sites (Catlin et al. 2024).

Protection of long-distance migrants like the Common Tern will also rely on Virginia’s neighbors. The availability of staging sites, which are post breeding congregation areas, is critical for the continued feeding of juveniles in preparation for migration. Birds from Rip Raps Island have been resighted on staging grounds in Maryland (Springer et al. 2025). As with many other beach-nesting species, Common Terns can be protected by restricting disturbance from beachgoers and dogs around their nesting and staging sites.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Arnold, J. M., S. A. Oswald, I. C. T. Nisbet, and M. A. Patten (2020). Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.comter.01.

Bailey, H. B. (1876). Notes on birds found breeding on Cobb’s Island, VA between May 25th and May 29th, 1875. Quarterly Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 1:24–28.

Catlin, D. H., D. Gibson, K. L. Hunt, C. E. Weithman, R. Boettcher, R. Gwynn, S. M. Karpanty, J. D. Fraser, S. Ritter, and S. M. Maxwell (2024). Movement patterns of foraging common terns (Sterna hirundo) breeding in an urban environment in coastal Virginia. PLOS ONE 19:e0304769.

Kain, T. (1985). Common Terns nest on a man-made island at Hampton. The Raven 56:43–44.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Springer, B. C., J. D. Sullivan, D. J. Prosser, K. E. Rambo, and J. J. Price (2025). Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) use of a staging site in the Chesapeake Bay. Northeastern Naturalist 31:555–564.

Sweeney, C., K. Hunt, J. Fraser, and S. Karpanty (2024). Assessing avian response to the relocation of Virginia’s largest seabird colony, 2024 annual report. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2019). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2018 breeding season. CCBTR-19-06. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Watts, B. D., B. J. Paxton, R. B., and A. L Wilke (2024). Status and distribution of colonial waterbirds in coastal Virginia: 2023 breeding season. CCBTR-24-12. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA.

Williams, B., R. A. Beck, B. Akers, and J. W. Via (1990). Longitudinal surveys of the beach nesting and colonial waterbirds of the Virginia barrier islands. Virginia Journal of Science 41:381–388.