Introduction

The Common Nighthawk is a medium-sized bird with long, pointed wings adorned by conspicuous white patches. These field marks make it easy to identify as it careens through the sky in search of flying insects, but it is often its buzzy peent vocalization that first alerts birders to its presence. The Common Nighthawk’s name is misleading, as it is unrelated to hawks or other raptors and belongs to the family Caprimulgidae, which includes Virginia’s two other nightjar species, the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus) and Chuck-wills-widow (Antrostomus carolinensis) (Brigham et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

A lack of breeding observations, owing to the species’ crepuscular nature, prevented the development of distribution models for the Common Nighthawk. For more information on where this species occurs in Virginia, see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

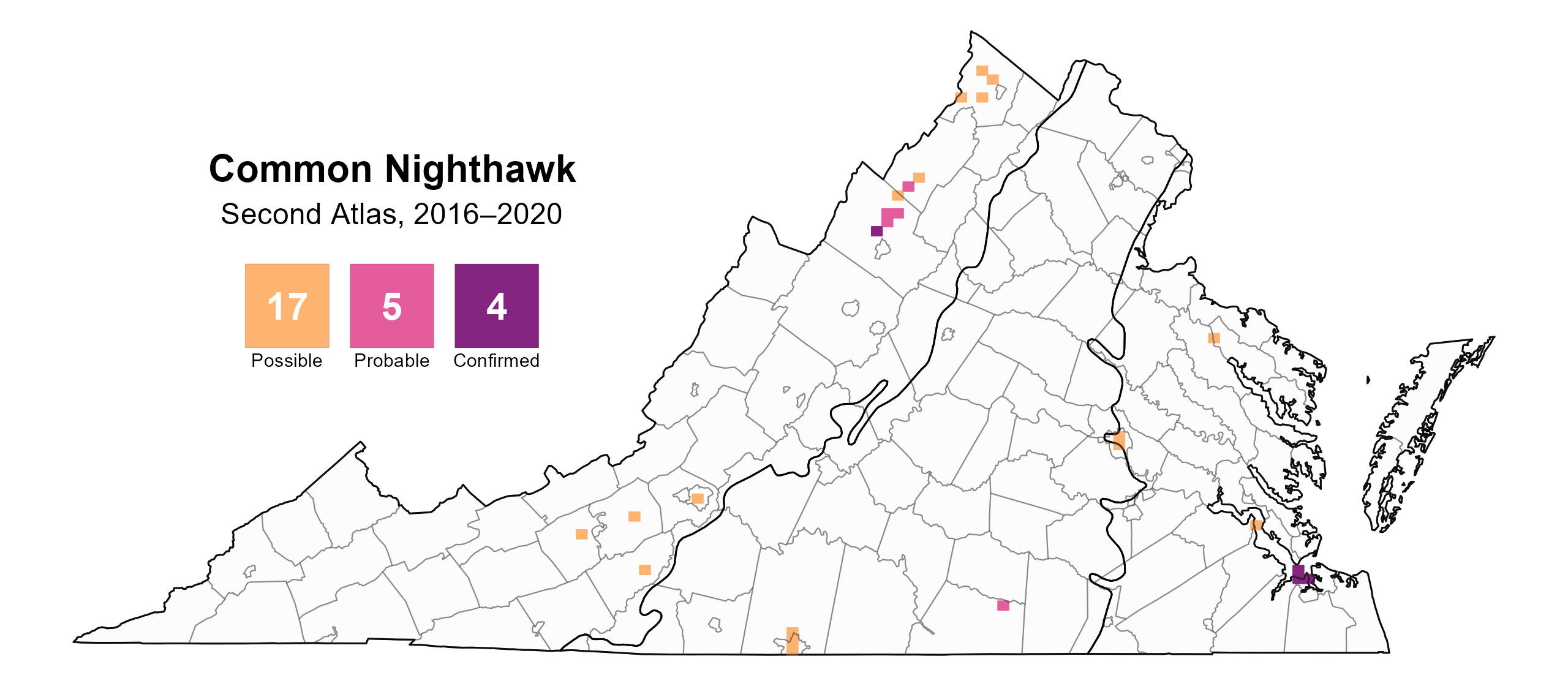

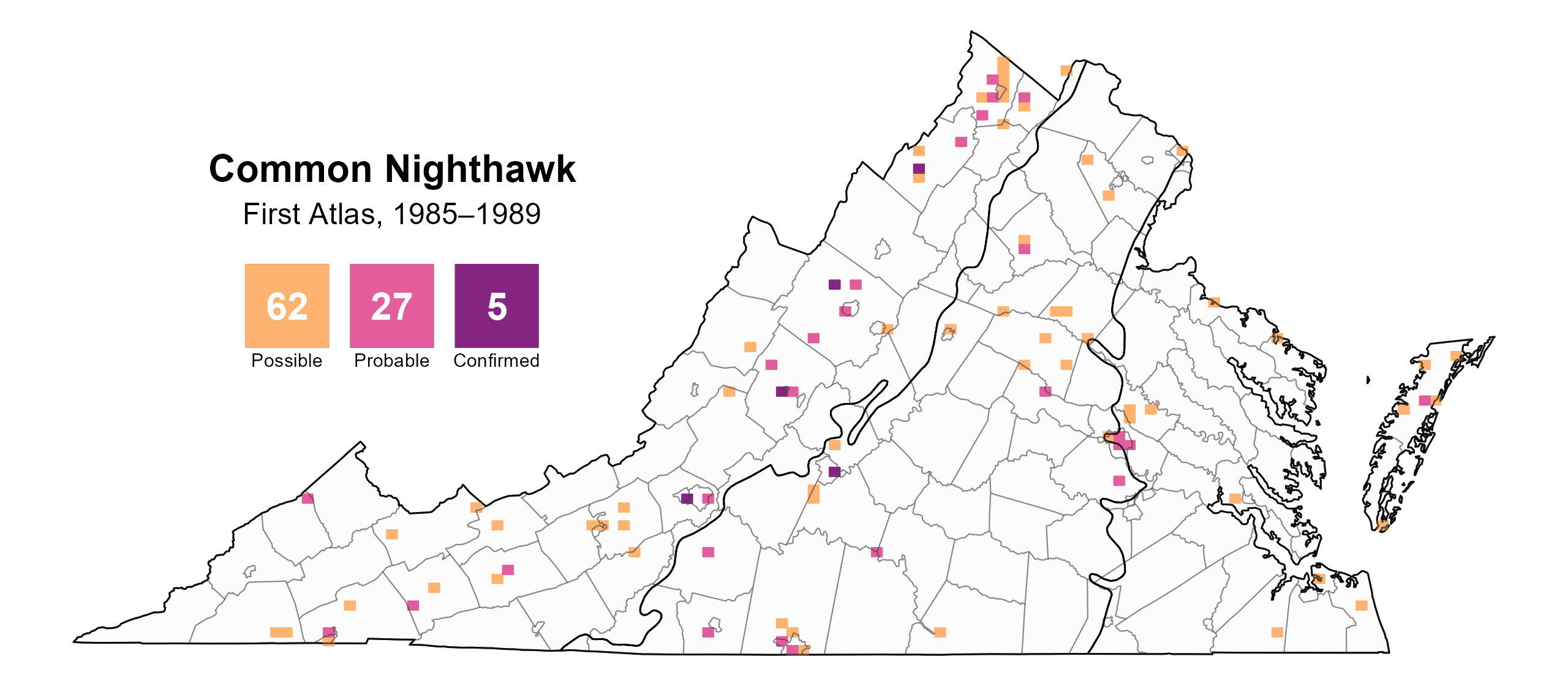

Common Nighthawks are considered uncommon to fairly rare (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007) and are patchily distributed in all three regions of Virginia. They were confirmed breeders in three blocks on Craney Island in the city of Portsmouth and in one block in the Grist Mill Road area in Rockingham County. They were found to be probable breeders in an additional three blocks in Rockingham County, as well as along S. Middle Road west of Mt. Jackson in Shenandoah County and Fleming Road in Mecklenburg County (Figure 1). A good number of behavioral observations related to probable breeding involved courtship displays, including detections of the characteristic “booming” sound produced during display dives. Breeding observations were recorded in substantially more blocks during the First Atlas than during the Second Atlas, despite greater survey effort during the latter (Figure 2). This is consistent with the species’ decline in the eastern U.S. (see Population Status section).

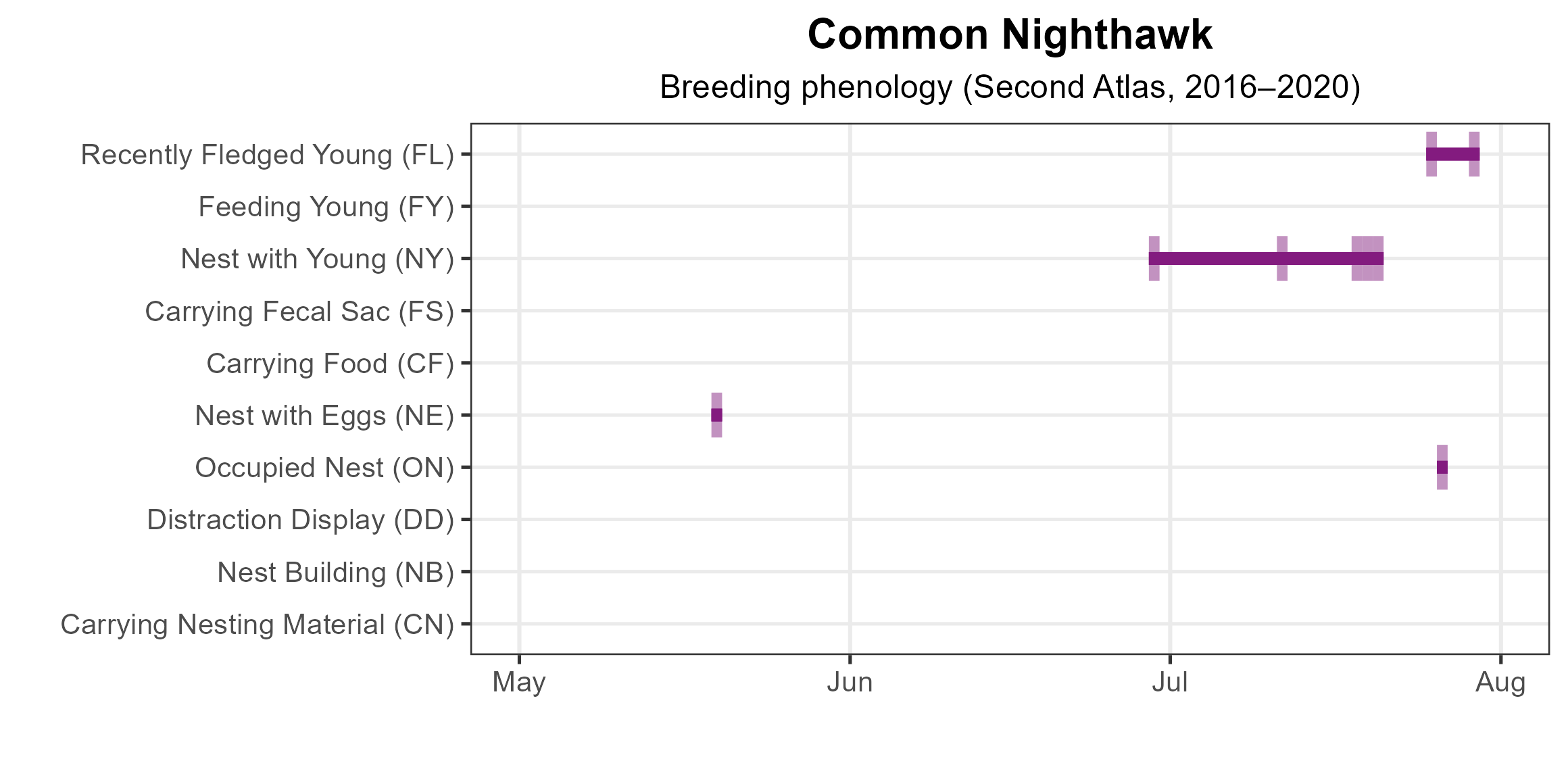

Common Nighthawks lay their well camouflaged eggs directly on the ground, making nests very difficult to find. Despite this, breeding confirmations were recorded based on observations of nests with eggs or young and of occupied nests, as well as of recently fledged young (Figure 3). A nest with eggs was observed on May 19, nests with young between June 29 and July 20, and recently fledged young were seen in late July.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Common Nighthawk breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Common Nighthawk breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Common Nighthawk phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

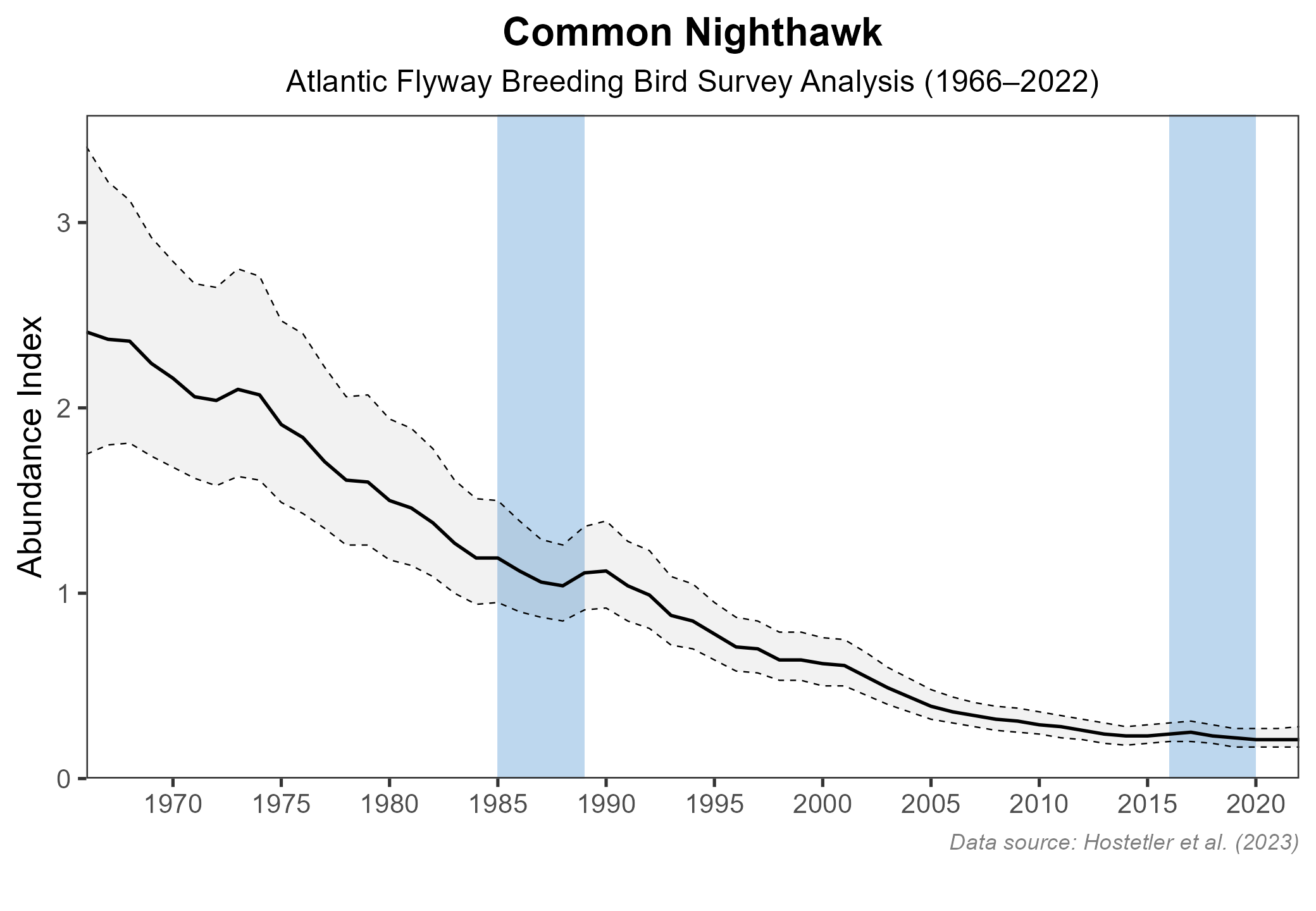

There were only four detections of Common Nighthawk in the point count data, preventing the development of an abundance model. Common Nighthawk population trends for Virginia derived from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) were not credible. However, BBS trends for the Atlantic Flyway region, which includes Virginia, indicate that the population decreased by a significant 4.23% annually from 1966–2022, with a slightly greater annual decrease of 4.74% between Atlas periods from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Common Nighthawk population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Like other birds that rely on aerial insects, Common Nighthawks are showing steep and steady population declines in the eastern part of their range in the U.S., including Virginia (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Due to this decline and the species’ relatively small population in Virginia, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan includes the nighthawk as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025).

Because of their crepuscular (nearly nocturnal) habits, Common Nighthawks can be difficult to study. To address these data gaps, in 2007 the Center for Conservation Biology at William and Mary established the Nightjar Survey Network. This volunteer-based program has worked to better document the distribution and population status of multiple nightjar species throughout the continental U.S., including Virginia (Wilson 2008). As of 2025, the Nightjar Survey Network is being coordinated by the Maine Natural History Observatory and Birds Canada. With collaboration from state wildlife agencies, the survey framework was improved to better estimate population trends at a regional level.

Across their continental range Common Nighthawks breed in a variety of open habitats, including coastal dunes, open forests and shrubby forest openings, rock outcrops, grassland habitats, and even flat gravel rooftops in urban areas (Brigham et al. 2020). The reasons for the decline in Common Nighthawks are not completely understood but are suspected to be related to habitat loss and declines in insect populations. A path toward better understanding the geographic and seasonal causes of nighthawk declines could include 1) the collection of ecological and reproductive data on their breeding grounds in association with habitat studies, paired with investigation of insect prey availability, and 2) movement tracking studies to understand where in South America the birds spend the winter and what threats they may face during the nonbreeding season (VDWR 2025). Common Nighthawks once commonly nested on flat-topped buildings of cities such as Richmond and Norfolk (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007); investigating the relationship between the loss of gravel rooftops and declines in urban nighthawk populations could yield insights and potential management recommendations. The plight of nightjar species has been gaining increasing attention, and coordination with the Atlantic Flyway and other groups on collaborative research and monitoring projects will be critical to making headway on reversing their declines.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Brigham, R. M., J. Ng, R. G. Poulin, and S. D. Grindal. 2020. Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor),version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY,USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.comnig.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M.D. 2008. The Nightjar Survey Network: program construction and 2007 Southeastern nightjar survey results. CCBTR-08-01. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 11 pp.