Introduction

In the Chesapeake Bay region, Clapper Rails utilize both high and low marsh habitats but maintain their highest densities in the low marshes; they also typically nest close to shorelines and tidal creeks as they use open, shallow water for foraging (Wilson et al. 2007). Like all rails, the Clapper Rail is notoriously secretive, lurking in marsh grasses. With specialized glands that secrete salt and eggs that can withstand inundation by tidal sea water, Clapper Rails are well-suited to breed in salt marshes (Rush et al. 2020). However, Clapper Rails also commonly breed in brackish marshes in Virginia, where they can overlap and even hybridize with King Rails (Rallus elegans) (Wilson et al. 2007).

Breeding Distribution

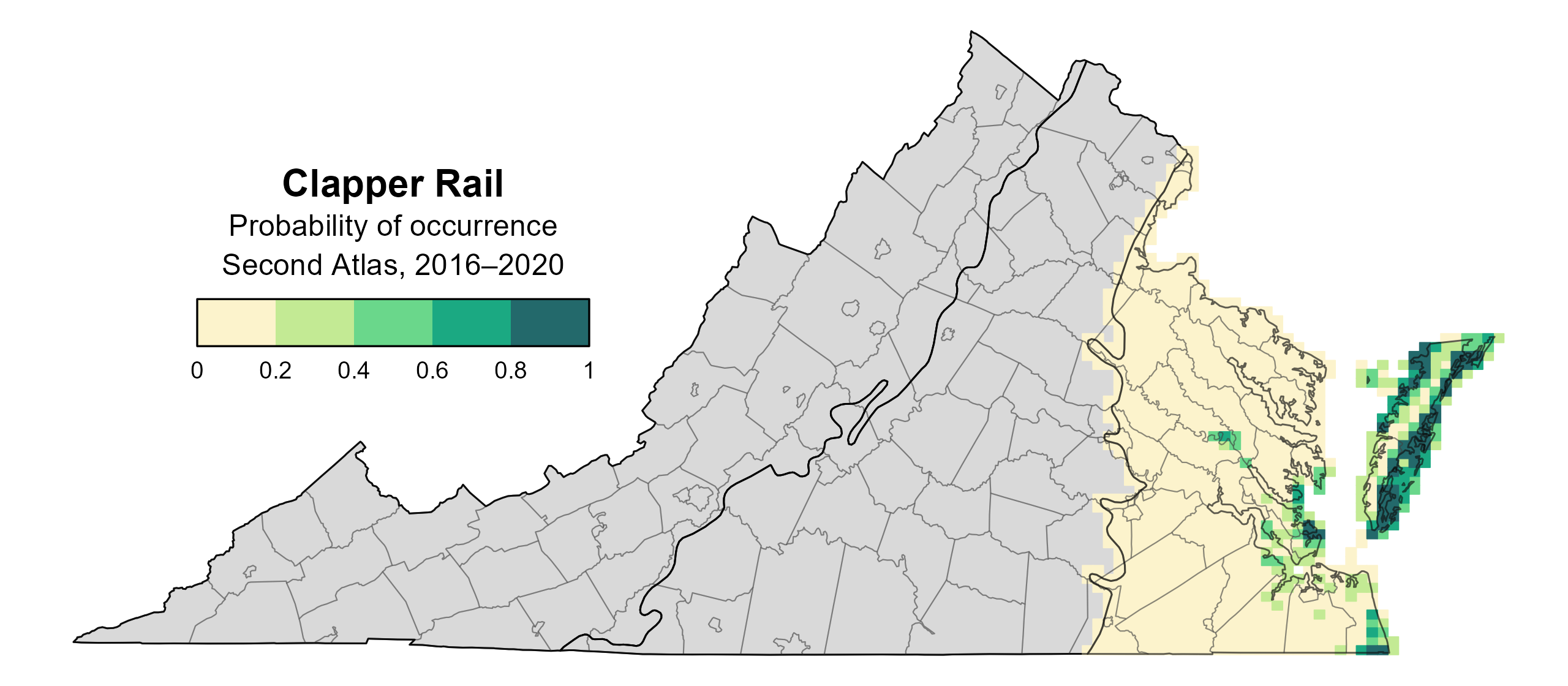

Clapper Rails are found only in the Coastal Plain region, where they are most likely to occur on the margins of the Eastern Shore, where salt marshes are plentiful, as well as areas of the Western Shore and the lower tidal reaches of a few of the major tributaries to Chesapeake Bay (Figure 1). The likelihood of a Clapper Rail being found in a block increases in blocks with marsh cover.

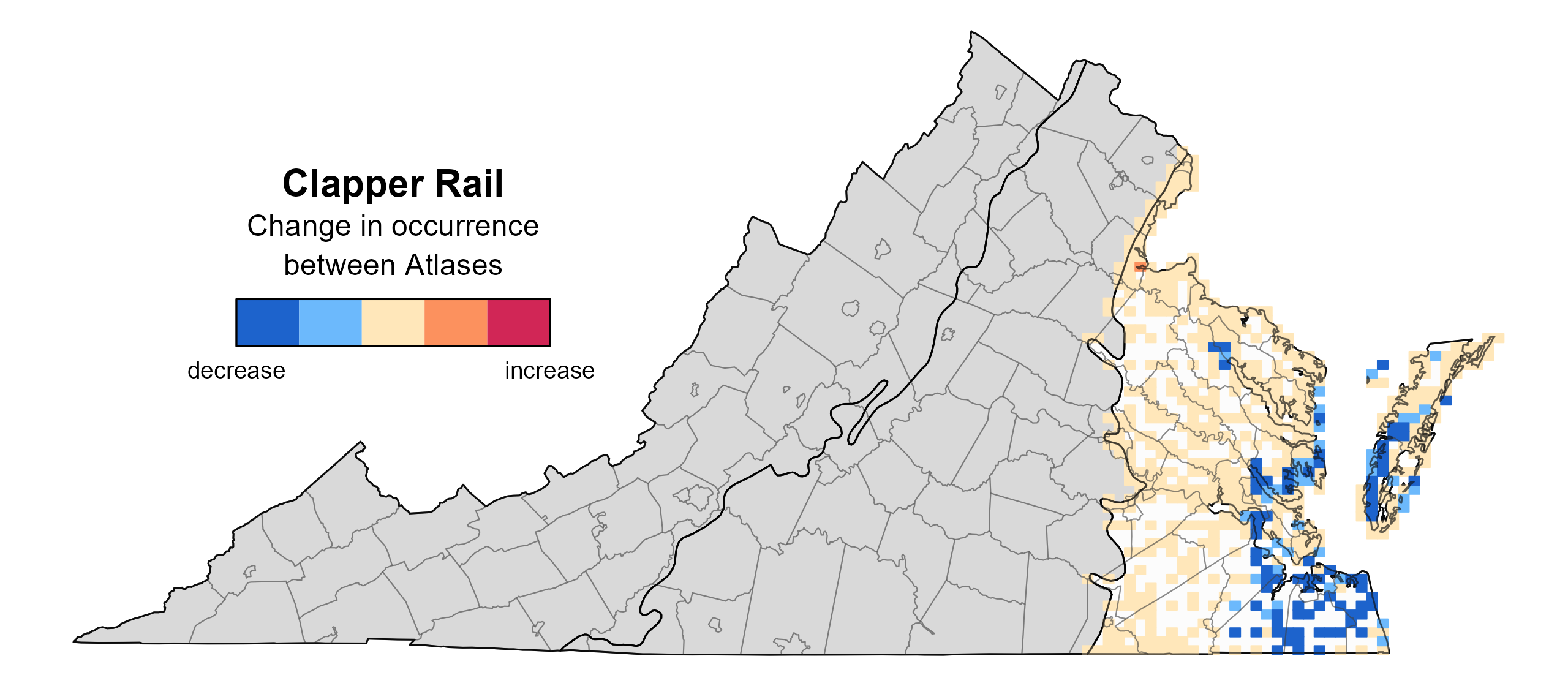

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), Clapper Rail’s likelihood of occurrence decreased across a widespread area of the southeastern Coastal Plain region, part of the Western Shore, and across much of the bayside of the lower Eastern Shore (Figure 3). This is consistent with the species’ declining population trend (see Population Status section).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Clapper Rail breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

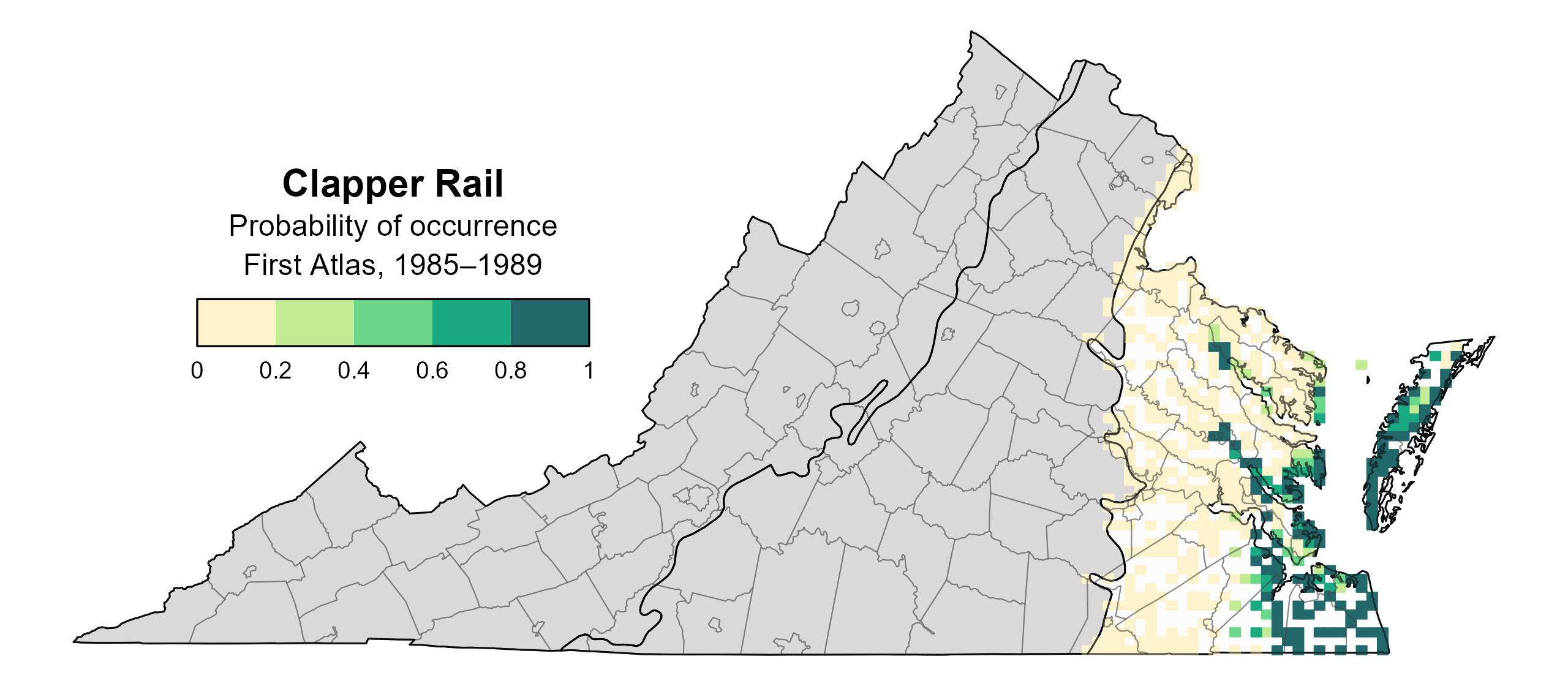

Figure 2: Clapper Rail breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Clapper Rail change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not sufficiently surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

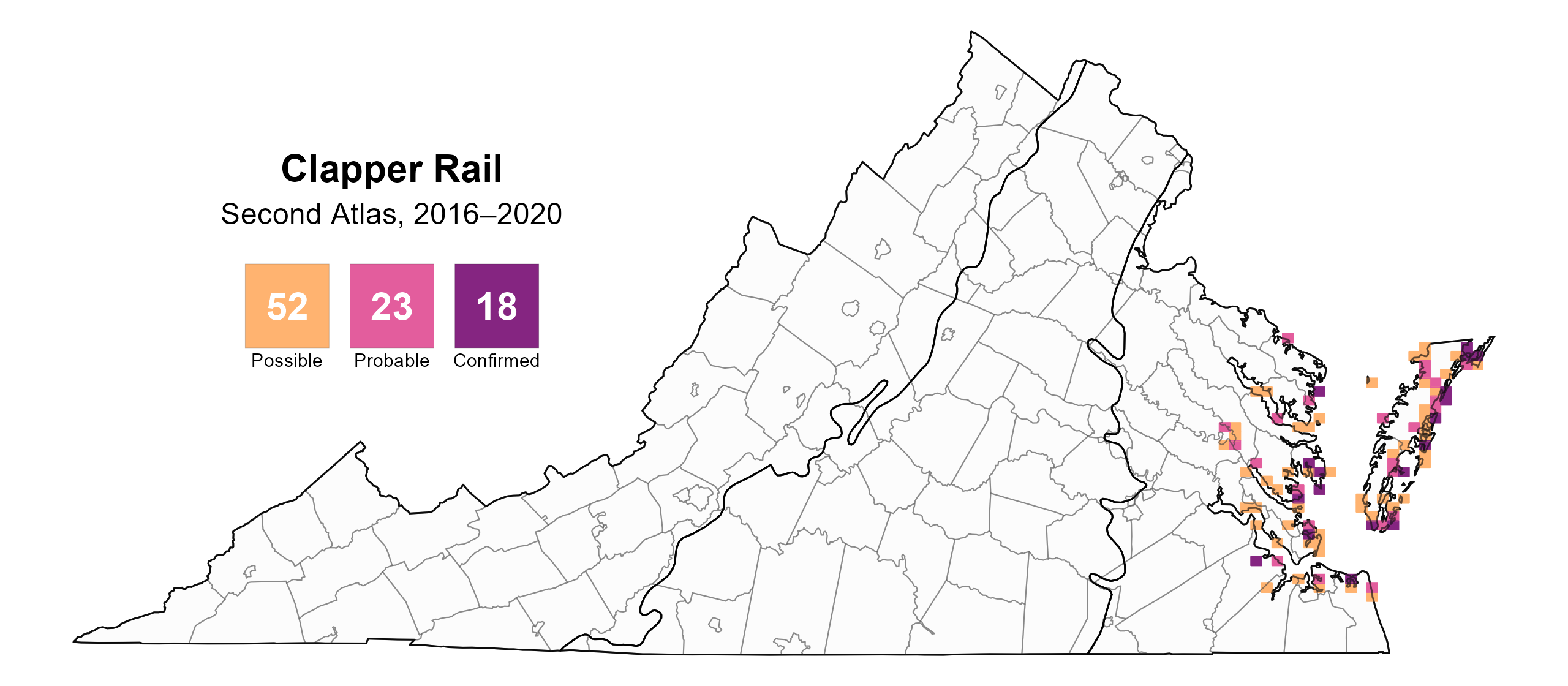

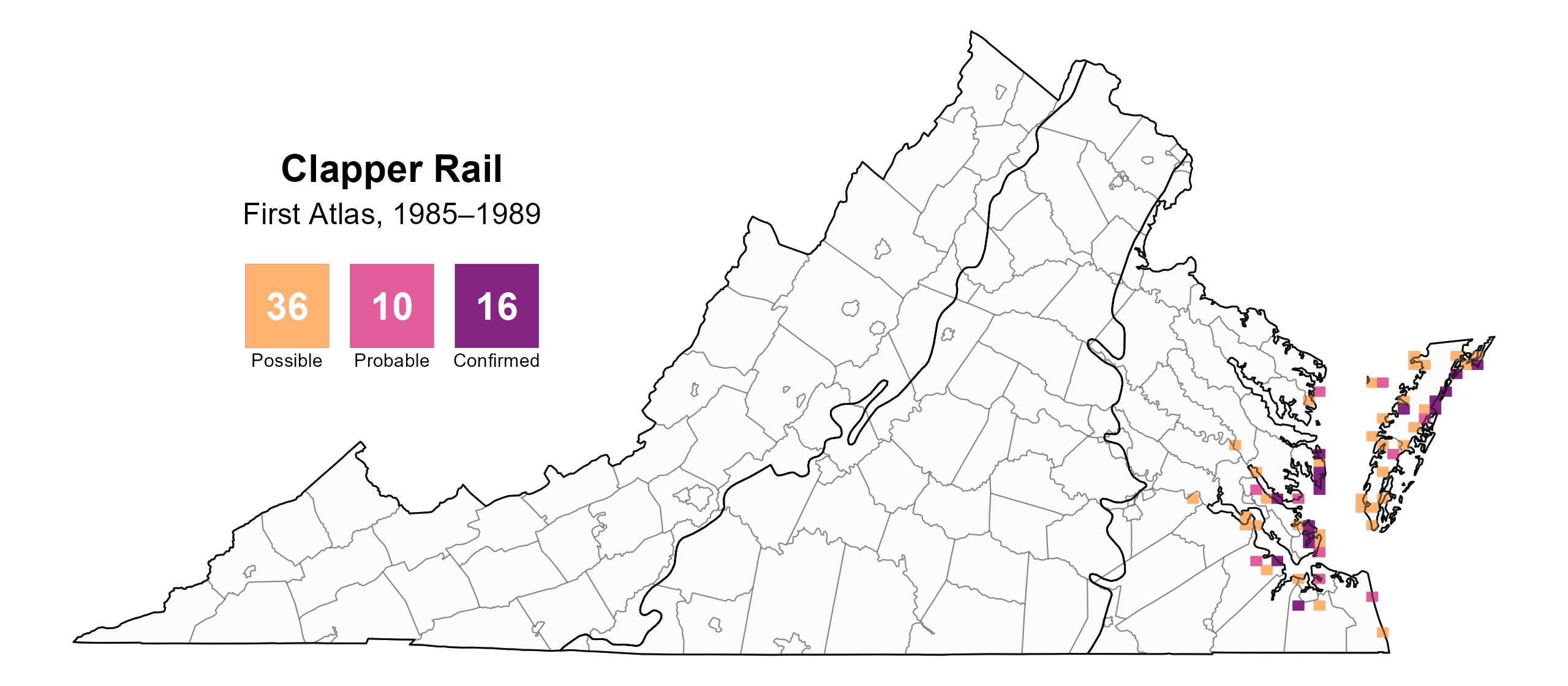

Clapper Rails were confirmed breeders in 18 blocks and six counties (Accomack, Gloucester, Isle of Wight, Mathews, Northampton, and Northumberland) and in the cities of Poquoson and Virginia Beach. They were probable breeders in three additional counties. Overall, Clapper Rails were documented in 93 blocks. Detections were most abundant in marshes of coastal areas of the Coastal Plain region and in the lower reaches of the major tributaries to the Chesapeake Bay (Figure 4). During the First Atlas, breeding observations followed a similar pattern. Although the Clapper Rail was recorded in approximately one third fewer blocks during the First Atlas than the Second Atlas, volunteer effort during the First Atlas was also considerably less (Figure 5).

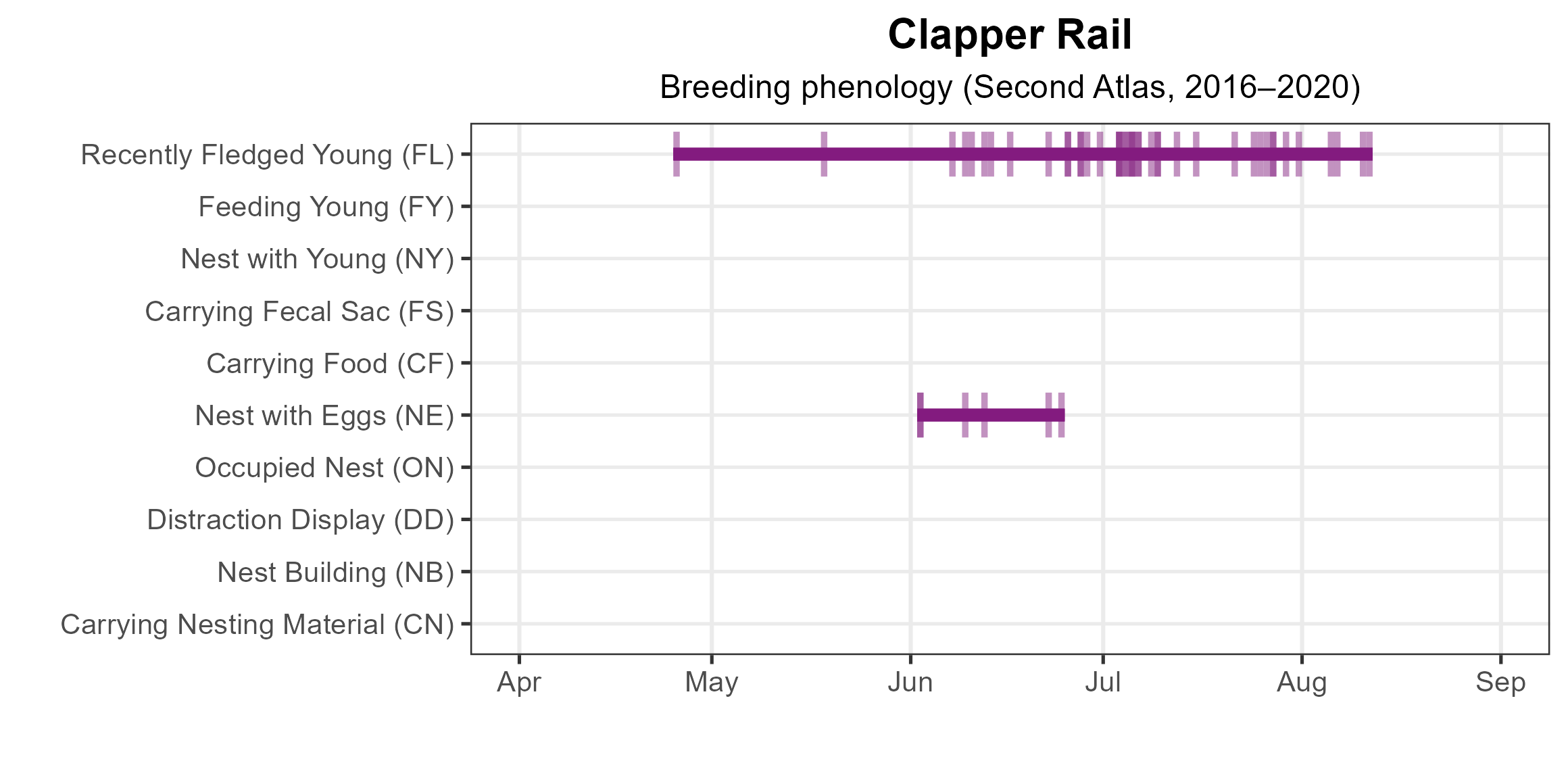

Breeding was confirmed mostly through observing recently fledged young (April 25 – August 11) (Figure 6). Given that the Clapper Rail nests in dense marsh vegetation, there were only five observations of nests with eggs (June 2 – June 24).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Clapper Rail breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Clapper Rail breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Clapper Rail phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

The North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) does not detect Clapper Rail in Virginia, and no credible population trends for the broader region could be generated (Hostetler et al. 2023). However, targeted marsh bird surveys by Correll et al. (2017) estimated a 4.6% annual decline (1998–2012) in the species for the Atlantic region from Maine to Virginia. Although Clapper Rails are undoubtedly declining In Virginia, these declines may not be as severe as those estimated by Correll et al. (2017).

Conservation

The Clapper Rail has a more restricted range-wide distribution than the closely related King Rail (Pickens and Meanley 2020; Rush et al. 2020). In Virginia, however, the reverse is true, with the Clapper Rail also being more numerically abundant than the King Rail. Based on its ongoing declines and population size, the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan classifies the Clapper Rail as a Tier IV (moderate conservation need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need (VDWR 2025).

Along with many other bird species that depend on marshes, Clapper Rails face multiple threats related to marsh loss and modification. Without the addition of new sediment, marshes can settle over time, causing them to sink through a process known as subsidence. This process can lead to the loss of marsh habitat. Marshes are also lost to rising sea levels, which can be mitigated if marshes are allowed to migrate into adjoining uplands, although erosion control and coastal development can interfere with this natural process (Wilson et al. 2007). The expansion of invasive species such as common reed (Phragmites australis) can also degrade marsh habitat and interfere with tidal flow (Rush et al. 2020). Proper marsh management, ongoing marsh protection and planning, and mitigation for sea-level rise are needed to stem future declines in Clapper Rail in Virginia and beyond.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Correll, M. D., W. A. Wiest, T. P. Hodgman, W. G. Shriver, C. S. Elphick, B. J. McGill, K. M. O’Brien, and B. J. Olsen (2017). Predictors of specialist avifaunal decline in coastal marshes. Conservation Biology 31:172–182.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Pickens, B. A., and B. Meanley (2020). King Rail (Rallus elegans), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.kinrai4.01

Rush, S. A., K. F. Gaines, W. R. Eddleman, and C. J. Conway (2020). Clapper Rail (Rallus crepitans), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.clarai11.01.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Wilson, M. D., B. D. Watts, and D. F. Brinker (2007). Status review of Chesapeake Bay marsh lands and breeding marsh birds. Waterbirds 30:122–137.