Introduction

The Cerulean Warbler gets its name from the male’s brilliant blue body plumage. Despite its vivid coloration, the species is more often detected through its buzzy song than by sight, as it often forages high in the forest canopy (Buehler et al. 2020). This habit has contributed to countless cases of “warbler neck” among birders straining to catch a glimpse of the bird.

Ceruleans breed in large tracts of moist deciduous forests with canopy gaps among tall trees (Wilson and Watts 2012; Wood et al. 2013; Buehler et al. 2020). There, they prefer to nest in white oak (Quercus alba) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum), where they build their nest on lateral branches next to a vertical twig (Wood et al. 2013).

Breeding Distribution

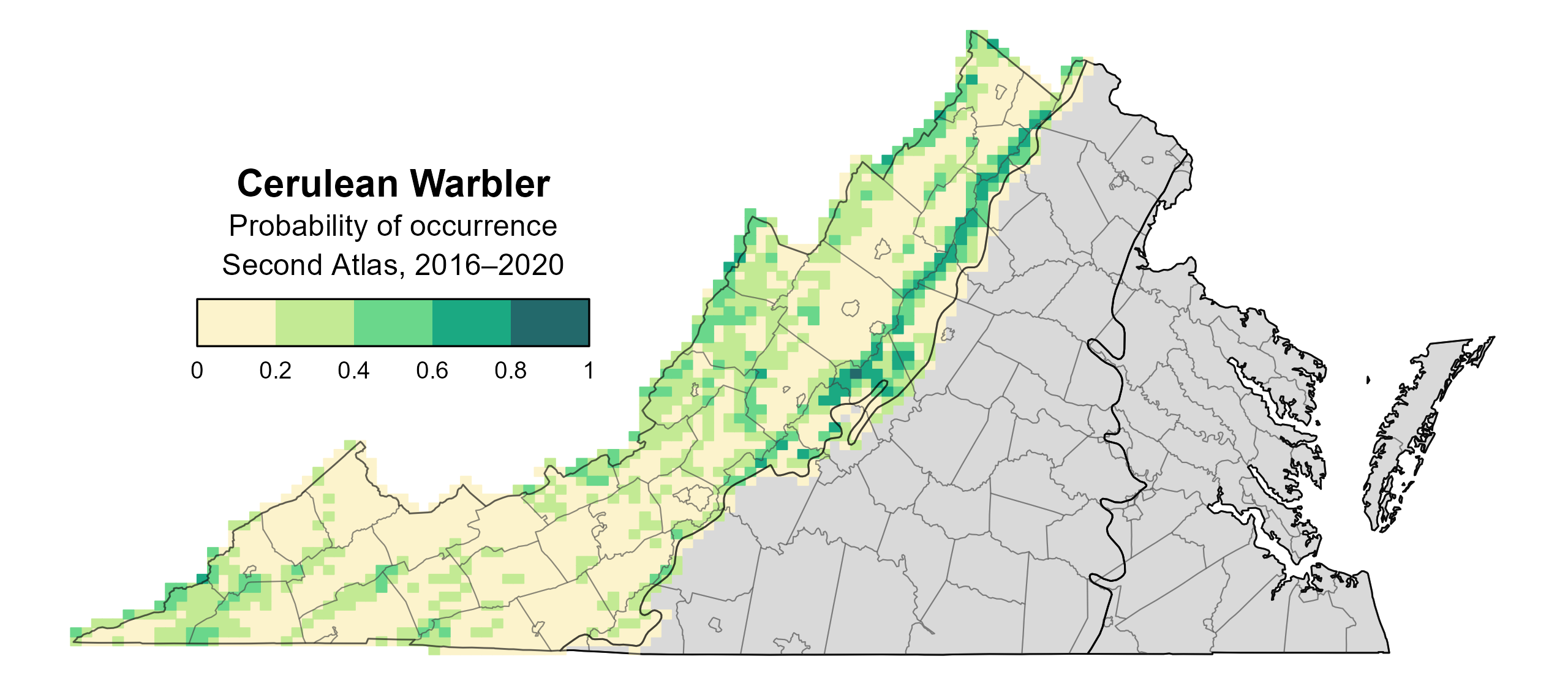

Cerulean Warblers are most likely to be found along the Blue Ridge Mountains and in isolated, high-elevation forests in the Ridge and Valley region of western Virginia (Figure 1). The species has a strong positive association with forest cover and to a lesser extent with young forest habitat. Additionally, it is strongly negatively associated with understory shrub cover. In aggregate, this illustrates that Cerulean Warblers are most likely to occur in blocks with extensive forest cover with relatively open understories, accompanied by areas of young forest.

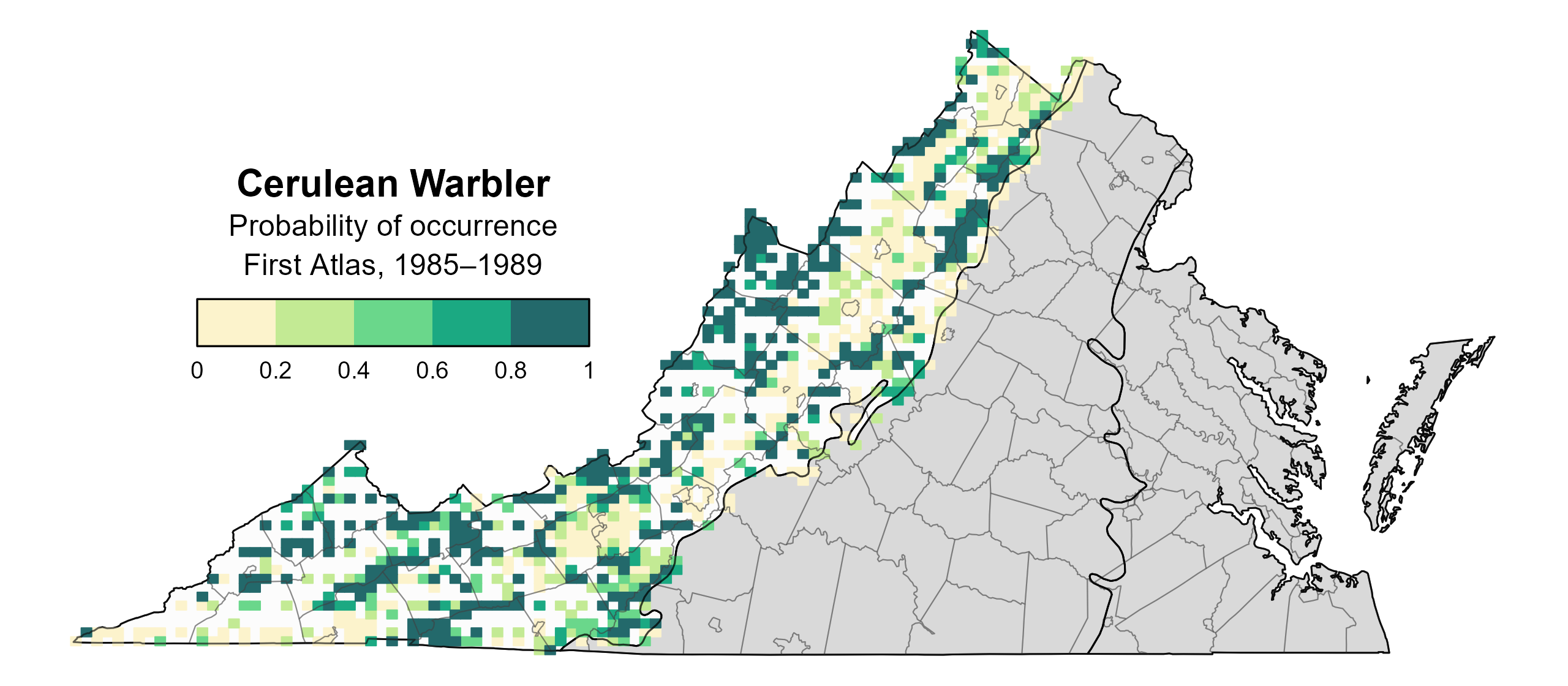

Between the First and Second Atlases (Figures 1 and 2), there was little change in the Cerulean Warbler’s likelihood of occurrence throughout the region, except for a decrease in Highland County and possible small areas of decrease the southern portion of the region (Figure 3).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Cerulean Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Cerulean Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Cerulean Warbler change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

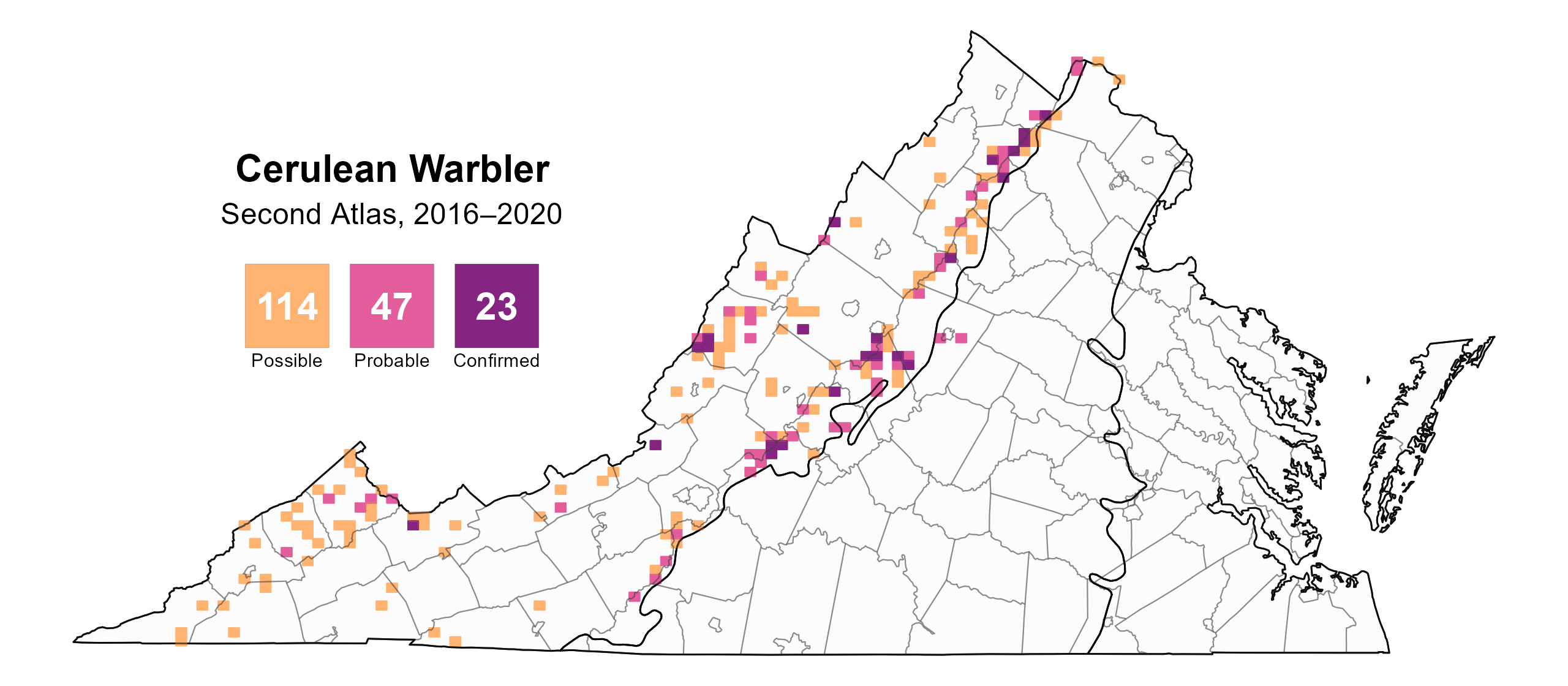

Cerulean Warblers were confirmed breeders in 23 blocks and 14 counties and found to be probable breeders in 11 additional counties. Most breeding observations were documented along the Blue Ridge Mountains, Allegheny Highlands, and Cumberland Mountains of southwestern Virginia (Figure 4). The species was also documented in four blocks within the Piedmont (Albemarle and Loudoun Counties). There were a few observations near the Fall Line in the Coastal Plain region during the First Atlas, where the species has been a rare, local, and irregular summer resident (Figure 5; Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007).

The earliest confirmation of breeding was of adults carrying nesting material on May 2 (Figure 6). Adults were also observed carrying food (June 1 – July 24) and feeding young (June 25 – July 13), and recently fledged young were documented between mid-June and August 7. Additionally, occupied nests were observed on May 25 and 26.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Cerulean Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Cerulean Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Cerulean Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

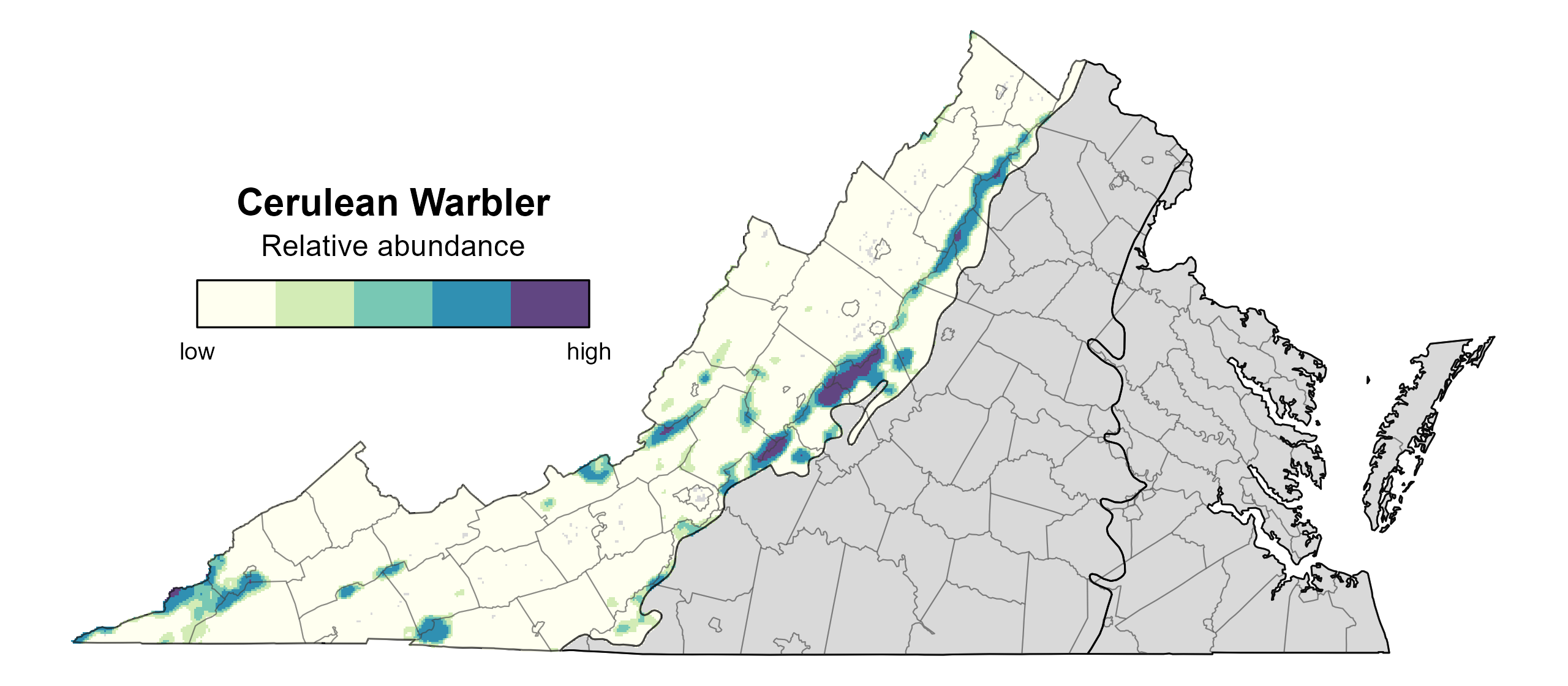

Cerulean Warbler relative abundance was estimated to be highest in a distinct line following the Blue Ridge Mountains, where extensive, high-elevation forest habitat is available (Figure 7). This includes areas within Shenandoah National Park and along the Blue Ridge Parkway, which are known to host robust populations of the species. Except for other areas on National Forest lands in southwestern Virginia, predicted abundance was low and diffuse throughout the remainder of the Mountains and Valley region.

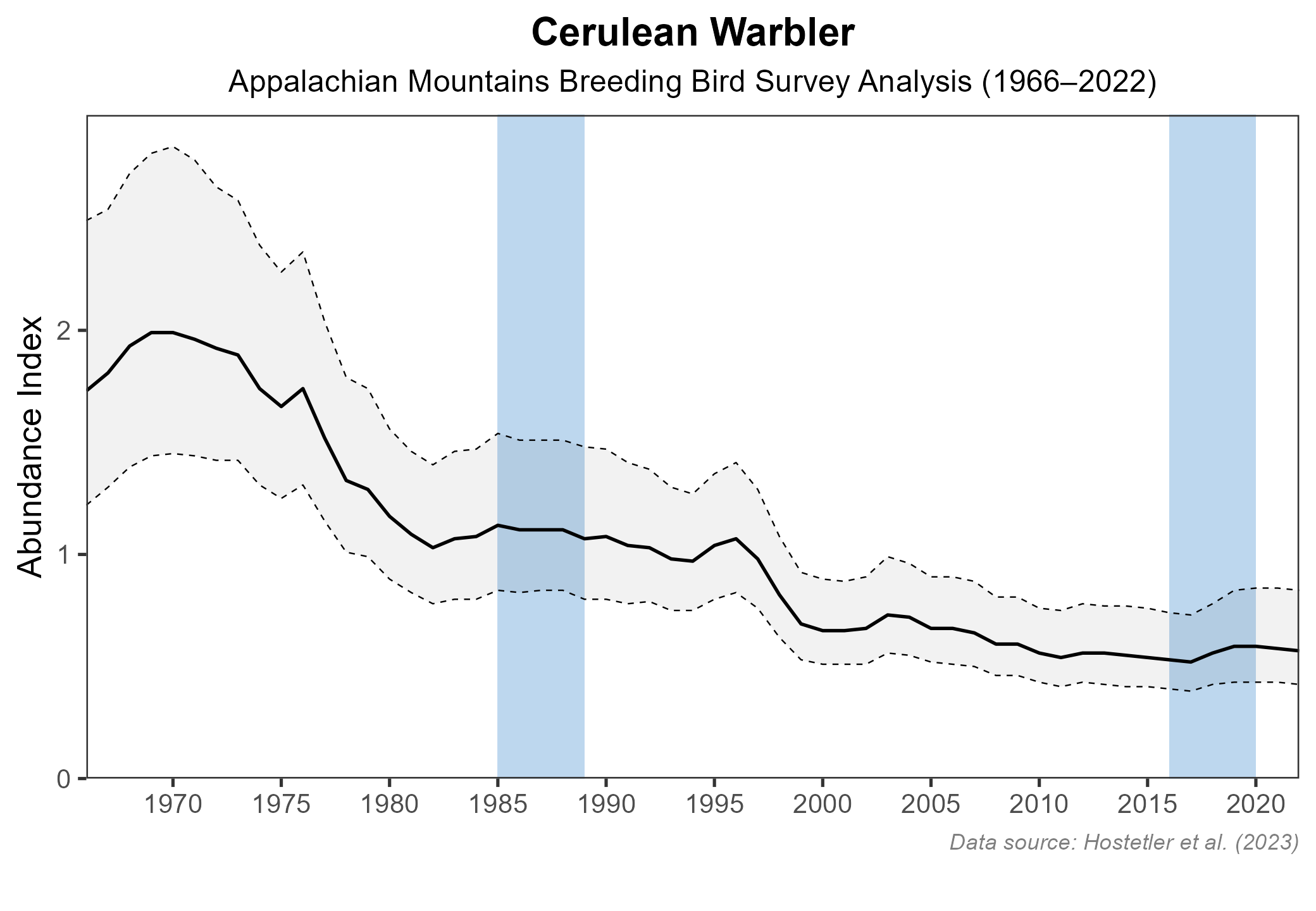

The total estimated Cerulean Warbler population in the state is approximately 11,000 detectable individuals (with a range between 6,000 and 22,000). Based on North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trend data for the Appalachian region (trends for Virginia are not credible), the Cerulean Warbler population declined by a significant 1.95% annually from 1966 to 2022 and experienced a significant decrease of 2.21% per year between Atlases from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8).

Figure 7: Cerulean Warbler relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high. Areas in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 8: Cerulean Warbler population trend for the Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because of its declining population, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ (VDWR) Wildlife Action Plan classifies the Cerulean Warbler as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Tier II: Very High Conservation Need). Its declines are thought to be due to habitat loss and degradation on both its breeding and wintering grounds (Wood et al. 2013). On its breeding grounds, the second-growth forests dominating the landscape lack the mid-story layers and more open canopy structure found in older forests (Wood et al. 2013). Disturbances such as ice storms, wildfires, windthrows, and insect outbreaks can create these conditions, as can forest management. Forestry Best Management Practices have been developed for the Appalachian population of Cerulean Warblers (Wood et al. 2013) and are being applied in high priority areas of the state through partnerships between the Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture, Virginia Department of Forestry, the U.S. Forest Service, VDWR, and others. Areas of high abundance have recently been documented on properties such as Gathright Wildlife Management Area (Lesley Bulluck, unpublished data). Identification of additional population strongholds for the species, beyond those already known, would help to focus management efforts.

Recent tracking work has established that the majority of Cerulean Warblers breeding in the Appalachian states, including Virginia, winter in the Andes Mountains of Colombia and Venezuela (Raybuck et al. 2022). Several conservation projects are underway on these wintering grounds to address threats such as forest loss that may be contributing to the decline of the species.

The Cerulean Warbler Technical Group, a partnership between state and federal agencies, non-governmental organizations and universities, is also leading the development of models to better understand where the population pinch-points are to better identify and address the factors driving population declines.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Buehler, D. A., P. B. Hamel, and T. Boves (2020). Cerulean Warbler (Setophaga cerulea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.cerwar.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Raybuck, D. W., T. J. Boves, S. H. Stoleson, J. L. Larkin, N. J. Bayly, L. P. Bulluck, G. A. George, K. G. Slankard, L. J. Kearns, S. Petzinger, J. J. Cox, and D. A. Buehler (2022). Cerulean Warblers exhibit parallel migration patterns and multiple migratory stopovers within the Central American Isthmus. Ornithological Applications 124:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/ornithapp/duac031.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist, 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Wilson, M., and B. Watts (2012). The Virginia avian heritage project: A report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, 12-04. William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA. 48 pp.

Wood, P.B., J. Sheehan, P. Keyser, D. Buehler, J. Larkin, A. Rodewald, S. Stoleson, T.B., Wigley, J. Mizel, T. Boves, G. George, M. Bakermans, T. Beachy, A. Evans, M. McDermott, F. Newell, K. Perkins, and M. White (2013). Management guidelines for enhancing Cerulean Warbler breeding habitat in Appalachian hardwood forests. American Bird Conservancy, The Plains, VA, USA.