Introduction

As its name suggests, the Canada Warbler’s breeding range lies mostly in Canada, though in the East, it extends through New England and into the southern Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia (Reitsma et al. 2020). This extension includes the Mountains and Valleys region in Virginia, where it can be found in high-elevation deciduous forests with dense understories (Harding et al. 2017). It is a charming warbler, well-worth the journey to its mountain haunts, with a bright eye-ring; a blazing-yellow chest draped in a necklace of loose, vertical spots; and a loud, sweet, and complex song.

Breeding Distribution

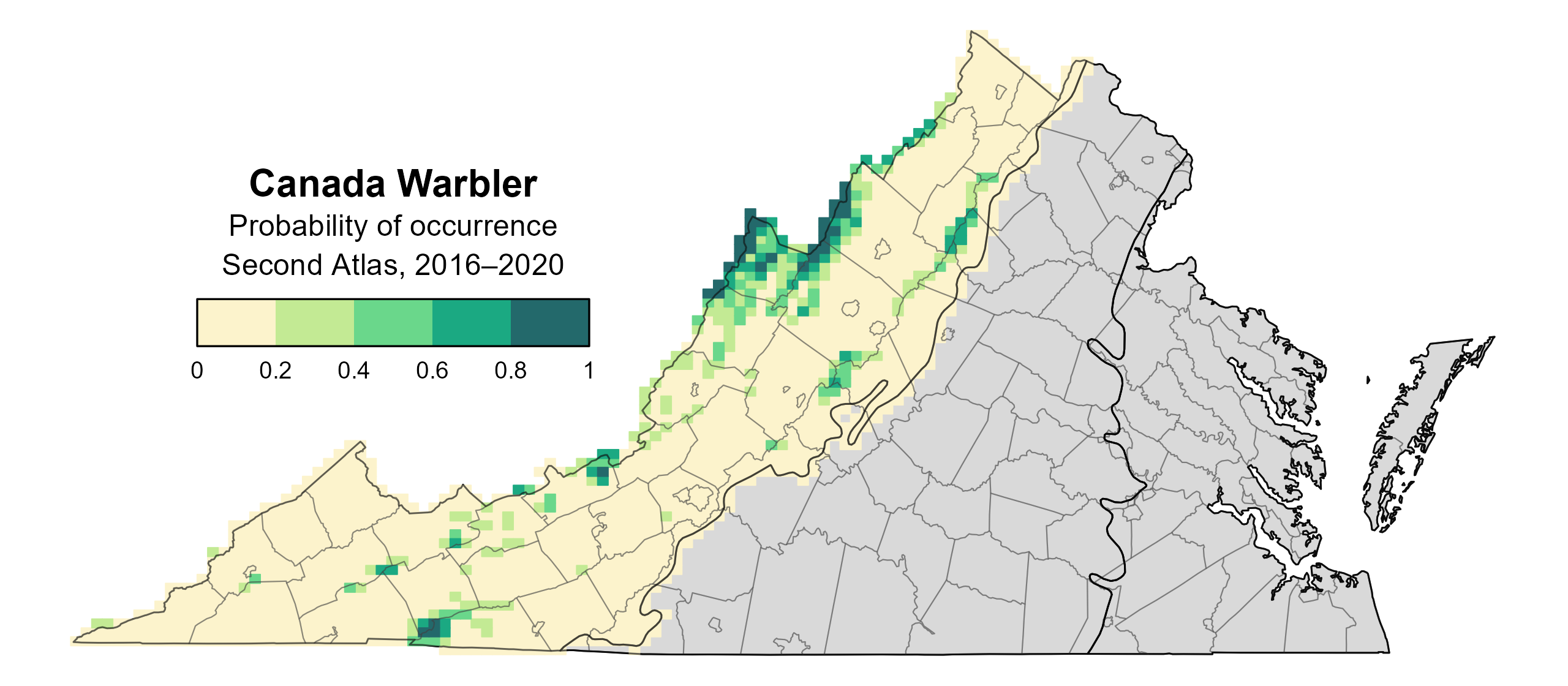

Canada Warblers are found only in the Mountains and Valleys region. There, they are most likely to occur in isolated areas of high-elevation forest habitat bordering West Virginia and in the Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 1). As such, Canada Warbler occurrence in a block is strongly positively associated with elevation. Counties showing concentrated areas with moderate to high occurrence include sections of Augusta, Bath, Giles, Grayson, Highland, Madison, Nelson, Page, Rockingham, and Smyth.

Due to data limitations, no distribution models could be developed for the First Atlas, and thus, no change in distribution between Atlas periods was modeled. For more information on where the species occurred during the First Atlas, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Canada Warbler breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray lie outside the species' core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

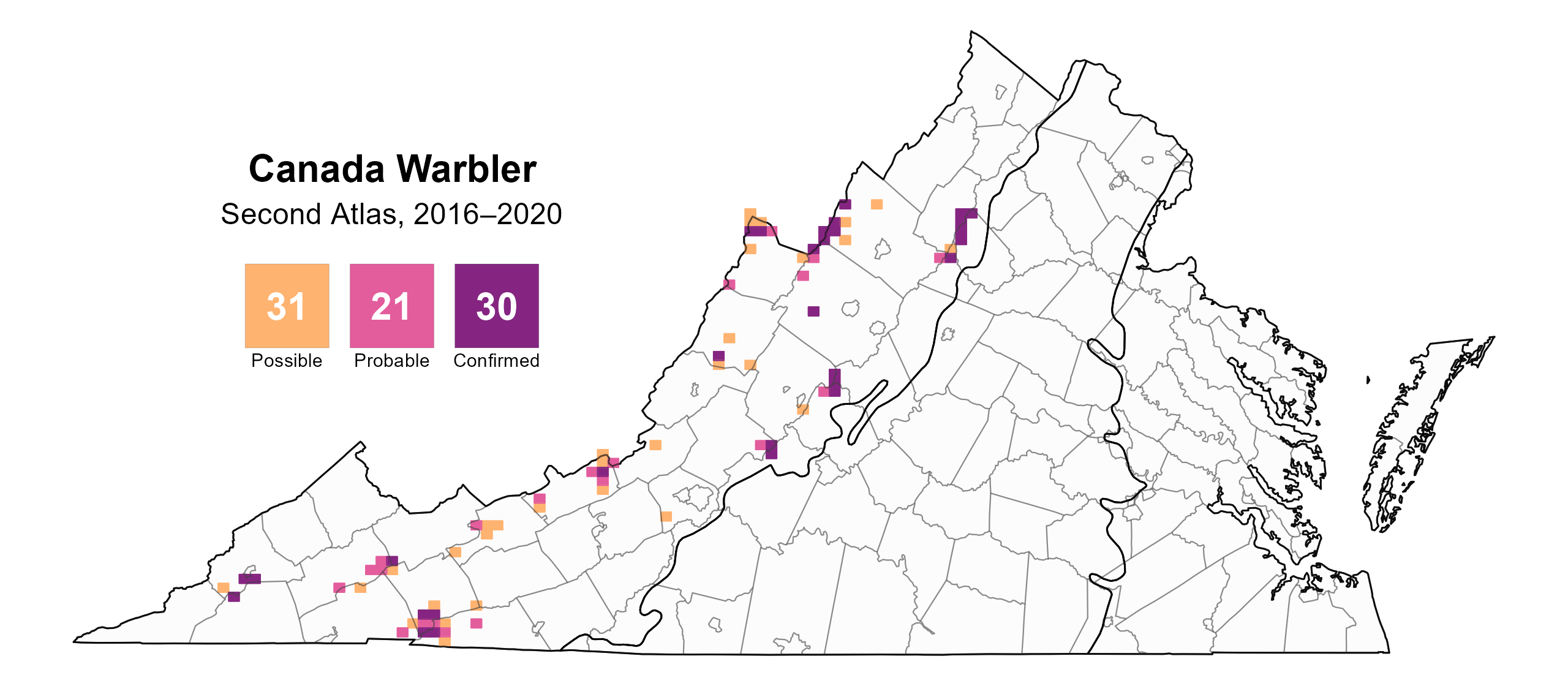

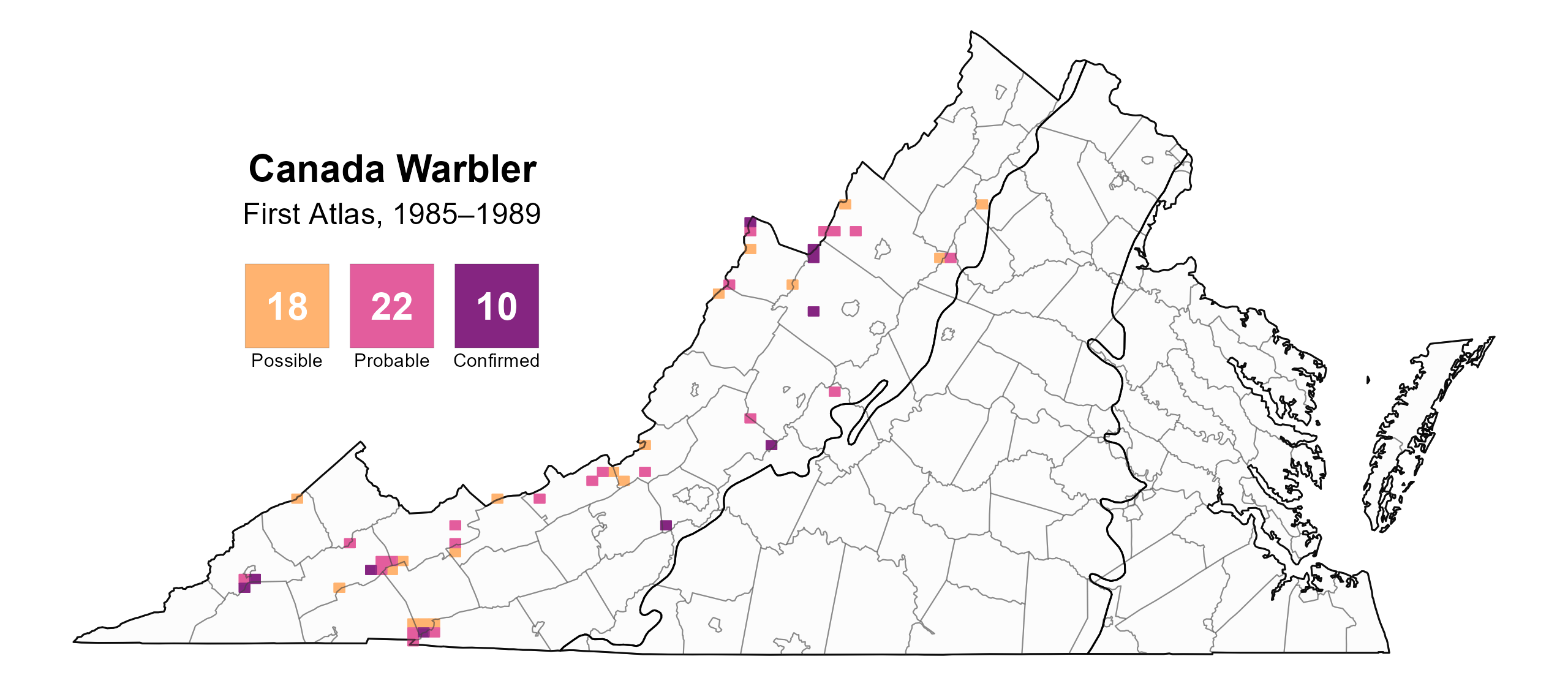

Canada Warblers were confirmed breeders in 30 blocks and 17 counties and found to be probable breeders in two additional counties; across breeding categories they were documented in a total of 82 blocks (Figure 2). The distribution of breeding observations was similar between the Second and First Atlases (Figures 2 and 3), although the species was detected in 50% more blocks during the Second Atlas. Given the declining trend for Canada Warbler (see Population Status section), this result is likely due to the greater survey effort expended during the Second Atlas but also suggests that the species has not lost ground in Virginia.

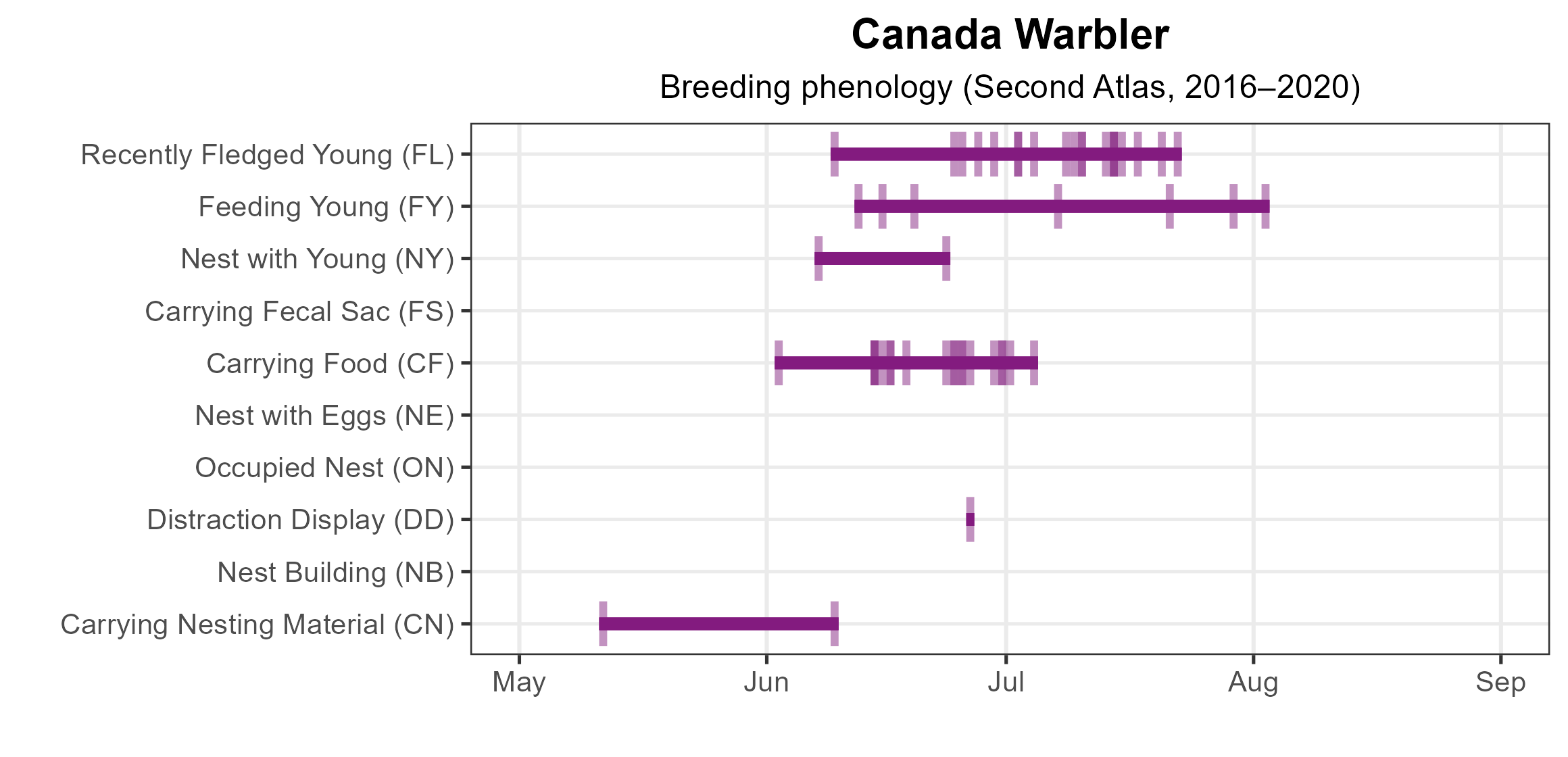

The earliest evidence of confirmed breeding was of adults carrying nesting material on May 11. Because Canada Warblers nest on or near the ground, their nests are difficult to observe. Breeding was in fact primarily confirmed through observations of adults carrying food (June 2 – July 4) and recently fledged young (June 9 – July 22) (Figure 4).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Canada Warbler breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Canada Warbler breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Canada Warbler phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

A total of 52 individual Canada Warblers were detected through the Atlas point count surveys. However, these data were not sufficient for the development of a robust abundance model. In Virginia, the species is documented from too few routes of the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) to allow for credible trends to be estimated. However, the BBS trend for the Appalachian Mountains region shows that the species experienced a significant decrease of 1.32% per year from 1966–2022; this trend was virtually identical (-1.33% annually) during the shorter inter-Atlas period from 1987–2018 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5).

Figure 5: Canada Warbler population trend for the Appalachian Mountains as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The Canada Warbler is declining throughout its range (Reitsma et al. 2020). Due to these declines, and to what is thought to be a relatively small population of the bird in Virginia, Virginia’s 2025 Wildlife Action Plan designates this species as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need) (VDWR 2025).

Lessig (2008) found the Canada Warbler to be well-distributed among high-elevation sites above 3,500 ft (1,067 m) in Virginia, although the species can be found at elevations as low as 2,800 ft (853 m) (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). This makes the species more resilient as it is not completely dependent on isolated, high-island forested habitats that are vulnerable to changes from shifting climatic conditions. Canada Warblers are positively associated with dense evergreen shrubs, such as thickets of rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum) and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) (Lessig 2008), and with streamside vegetation (Reitsma et al. 2020) within forests of eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) (Dunn and Garrett 1997). It is unknown whether the decline in hemlock due to the hemlock wooly-adelgid (Adelges tsugae) has had a negative impact on Canada Warbler in Virginia.

Forestry practices that contribute to removal of the shrub layer are also a major threat to the species on its breeding grounds (CWS and Birdlife International 2021). Loss of understory vegetation from over-browsing by white-tailed deer and invasive species further contribute to changes in forest structure that are thought to negatively impact breeding populations of Canada Warbler (Harding et al. 2017; Reitsma et al. 2020). These are all suspected, but not known, threats to the species in Virginia.

Recommendations related to conserving Canada Warbler habitat as well as best practices for conducting forestry operations and management are highlighted in Harding et al. (2017) and could be implemented in partnership with the Canada Warbler International Conservation Initiative and the Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture. Additionally, forest loss and degradation on breeding and wintering grounds are also factors likely contributing to the Canada Warbler’s decline (Harding et al. 2017). A coordinated multi-state tracking project would be a path toward identifying the Appalachian breeding population’s wintering grounds in Central and South America. This would allow an investigation of threats during the nonbreeding portion of the species’ life cycle. It would also foster collaboration and support of ongoing conservation activities to benefit the warbler in Latin America through initiatives such as Southern Wings.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) and Birdlife International (2021). The Canada Warbler full-life-cycle conservation action plan. Gatineau, Québec, Canada, and Quito, Ecuador.

Dunn, J. L., and K. L. Garrett (1997). A field guide to the warblers of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA, USA.

Harding, C., L. Reitsma, and J. D. Lambert (2017). Guidelines for managing Canada warbler habitat in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions. High Branch Conservation Services, Hartland, VT, USA.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Lessig, H. (2008). Species distribution and richness patterns of bird communities in the high elevation forests of Virginia. Master’s Thesis. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA.

Reitsma, L. R., M. T. Hallworth, M. McMahon, and C. J. Conway (2020). Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.canwar.02.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist, 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.