Introduction

The Brown Creeper, the sole representative of its family in the Western Hemisphere, is a familiar sight in winter as it flies upward around tree trunks. It is also a rare breeder in Virginia, where its inconspicuous behavior and isolated habitats make it hard to find. This species relies on undisturbed coniferous, mixed, and deciduous forests of the “boreal” conifer zone along the Appalachian Mountains (Poulin et al. 2020), where its breeding range extends into Virginia from a more concentrated northern distribution. Brown Creepers build a unique type of nest, formed to be just large enough for the bird in the space between peeling bark on large and often dead or dying trees (Poulin et al. 2020).

Breeding Distribution

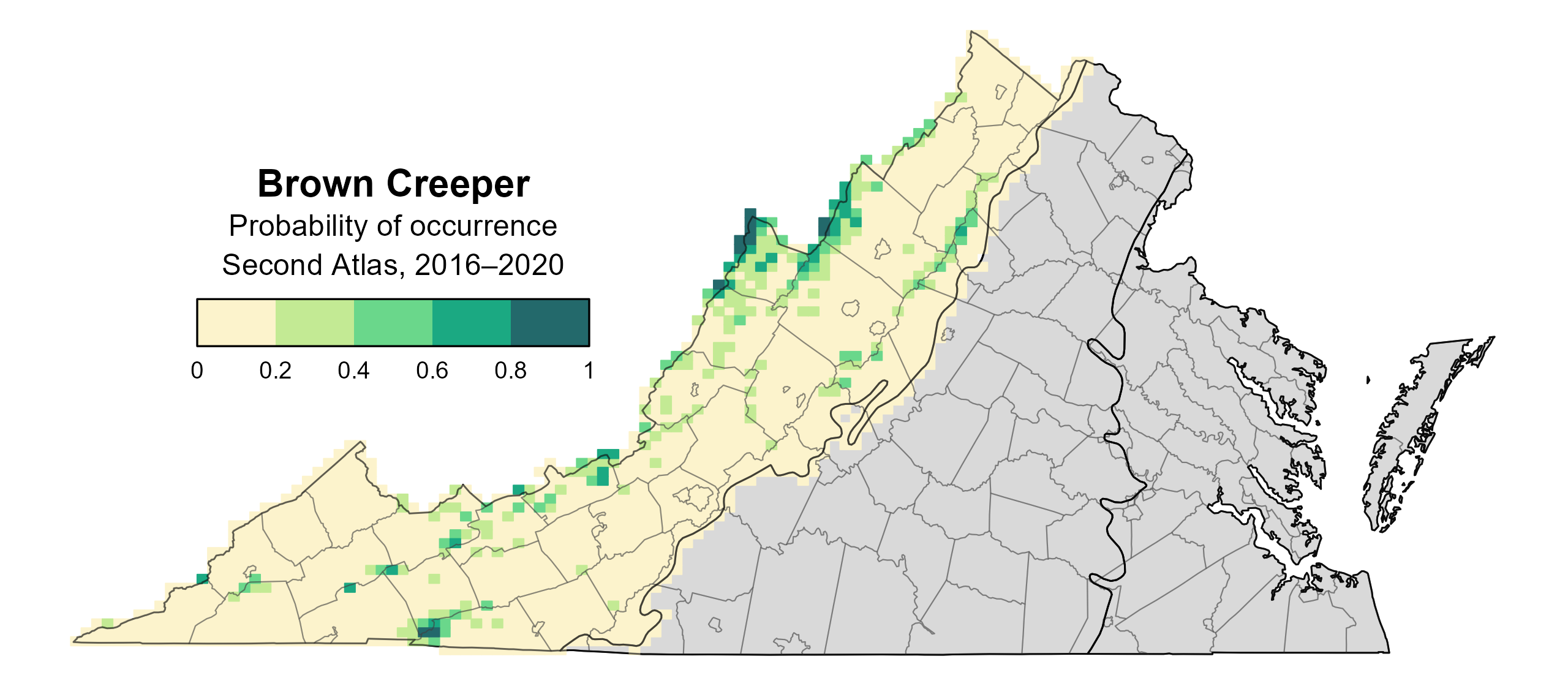

The breeding distribution of the Brown Creeper in Virginia is confined to higher elevations and more northern areas, with its presence during the summer months marking the eastern extent of its range along the Appalachian Mountains. Breeding occurs only in the Mountains and Valleys region. The likelihood of Brown Creepers occurring in a block is low overall throughout the region except for hotspots at Mount Rogers and Whitetop Mountain (Grayson and Smyth Counties) and Mountain Lake in Giles County, where the species was first documented breeding in the state in 1965 (see Mays 2006). The species is also highly likely to occur along the ridgeline at the West Virginia border in Highland and Rockingham Counties.

Generally, Brown Creepers occur above 4,000 ft (6,437 m) in elevation (Figure 1), but there are previous records indicating this species breeds at elevations as low as 2,100 ft (3,380 m) in Montgomery County (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Mays (2006) observed Brown Creeper breeding in old-growth, mixed coniferous-deciduous forests that only occur at these high elevations. Accordingly, the Second Atlas indicates that the likelihood of Brown Creeper occurring increases slightly with elevation. Brown Creepers are also somewhat more likely to occur in areas with larger forest patches.

Because of limited data, its distribution during the First Atlas and its change between the two Atlas periods could not be modeled. Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on this species’ distribution during the First Atlas.

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Brown Creeper breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

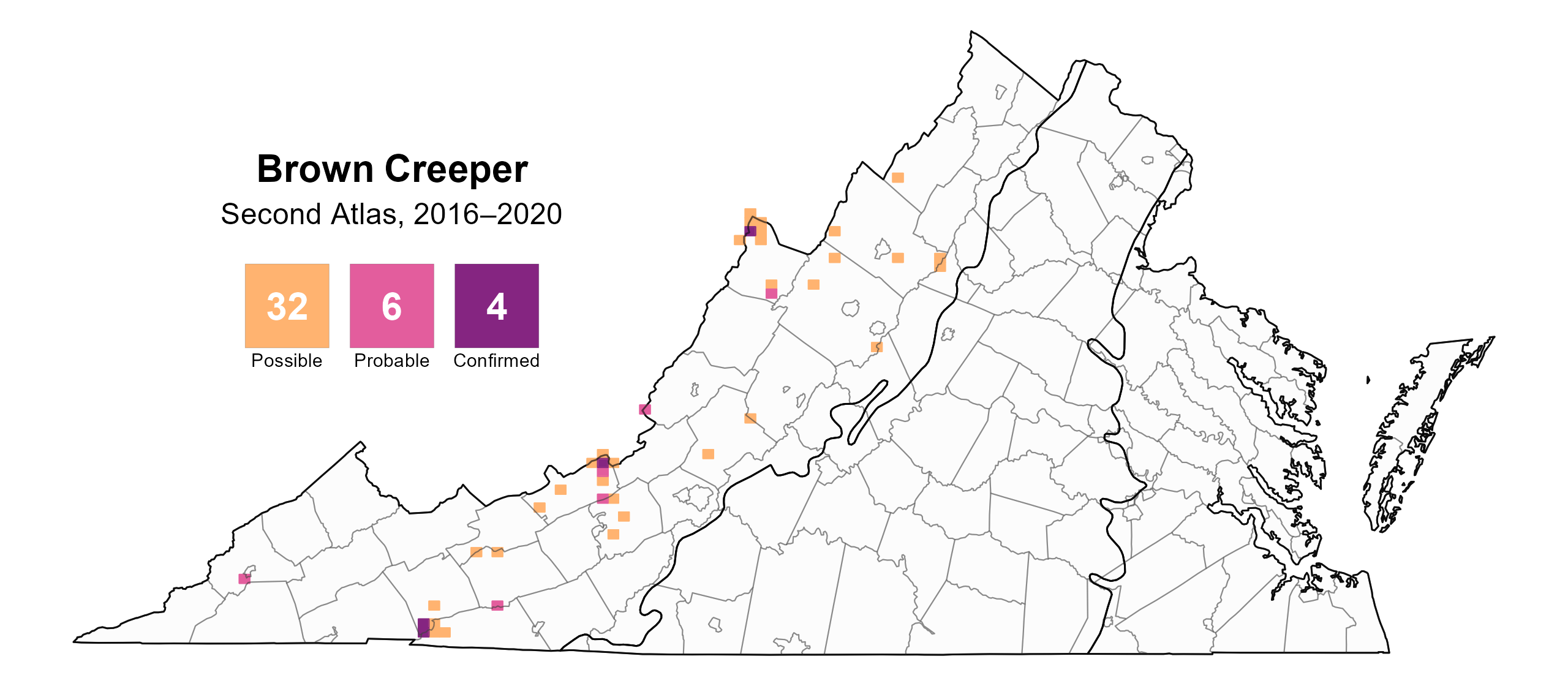

Brown Creepers were confirmed breeders in only four blocks and four counties (Figure 2). Breeding was confirmed at the following locations: Glen Alton Day Use Area (Giles County), Whitetop Mountain (Grayson County), the George Washington National Forest (Highland County), and the Blue Ridge Discovery Center (Smyth County). Breeding was probable in several additional locations: Alleghany County near the West Virginia border, the Jefferson National Forest (Montgomery County), High Knob (Wise County), Speedwell (Wythe County), and Hupman Valley (Highland County).

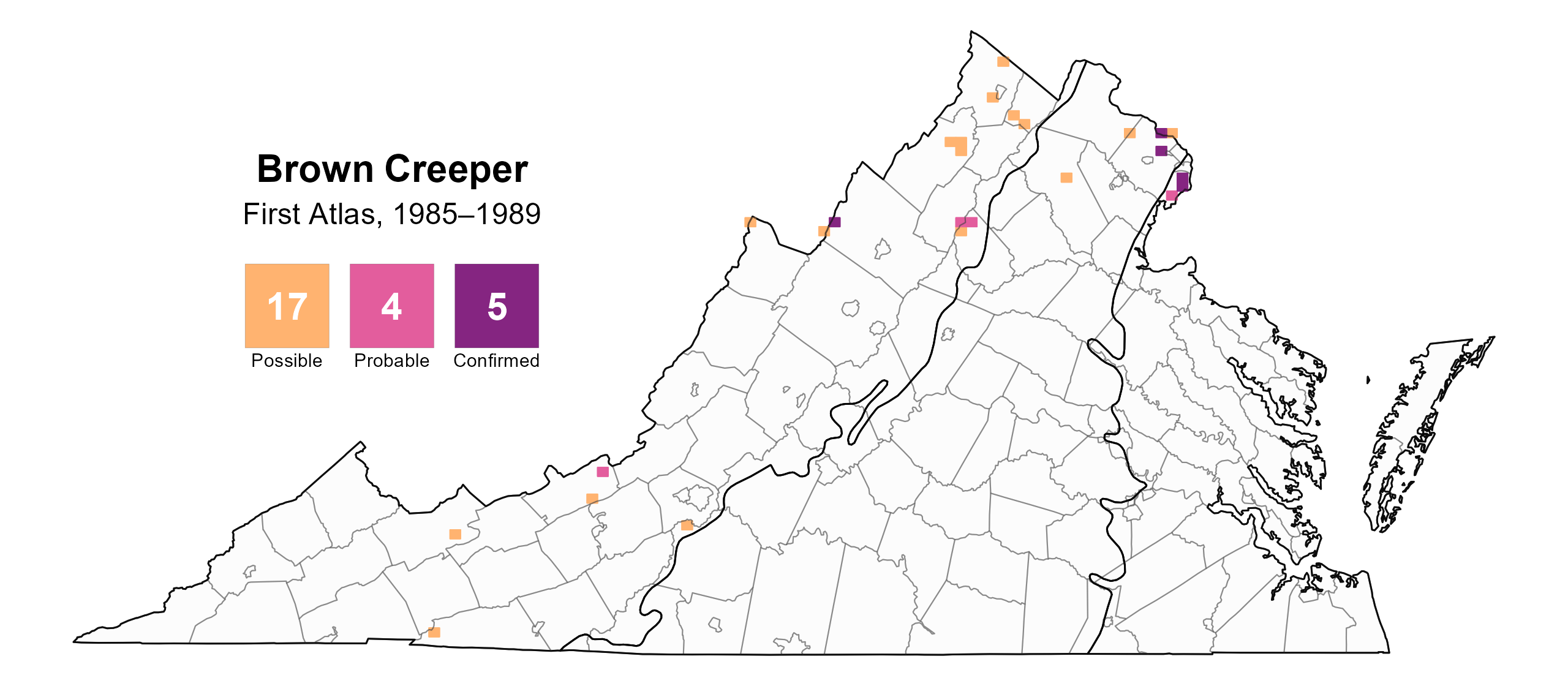

Despite several breeding confirmations in Fairfax County during the First Atlas (Figure 3), there were no probable or confirmed breeders in the Piedmont region in the Second Atlas, during which the species was restricted to the Mountains and Valleys region. This breeding population, which was previously observed in the vicinity of Turkey Run and along the Potomac south of Alexandria, may have disappeared as the area has been developed since the First Atlas, but the status and fate of this mysterious population remain unknown.

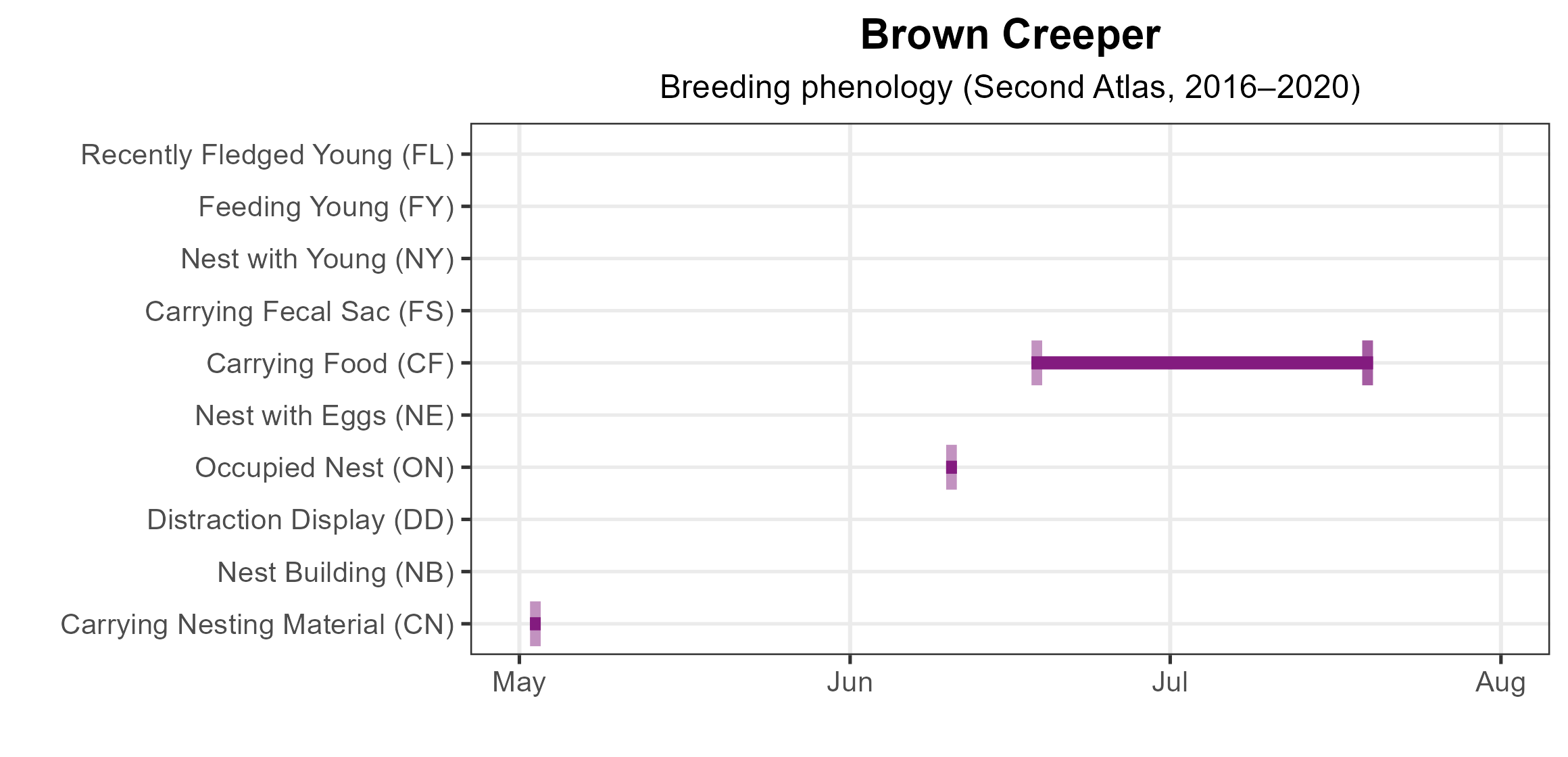

Most confirmations were from adults carrying food, and one record each of an occupied nest, a used nest, and adults carrying nesting materials were documented. Brown Creepers were seen carrying nesting material on May 2, on the nest on June 10, and carrying food from June 18 to July 19 (Figure 4). This species’ cryptic habits make it difficult to locate, especially when its range is so restricted in the state. For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 2: Brown Creeper breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Brown Creeper breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 4: Brown Creeper phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

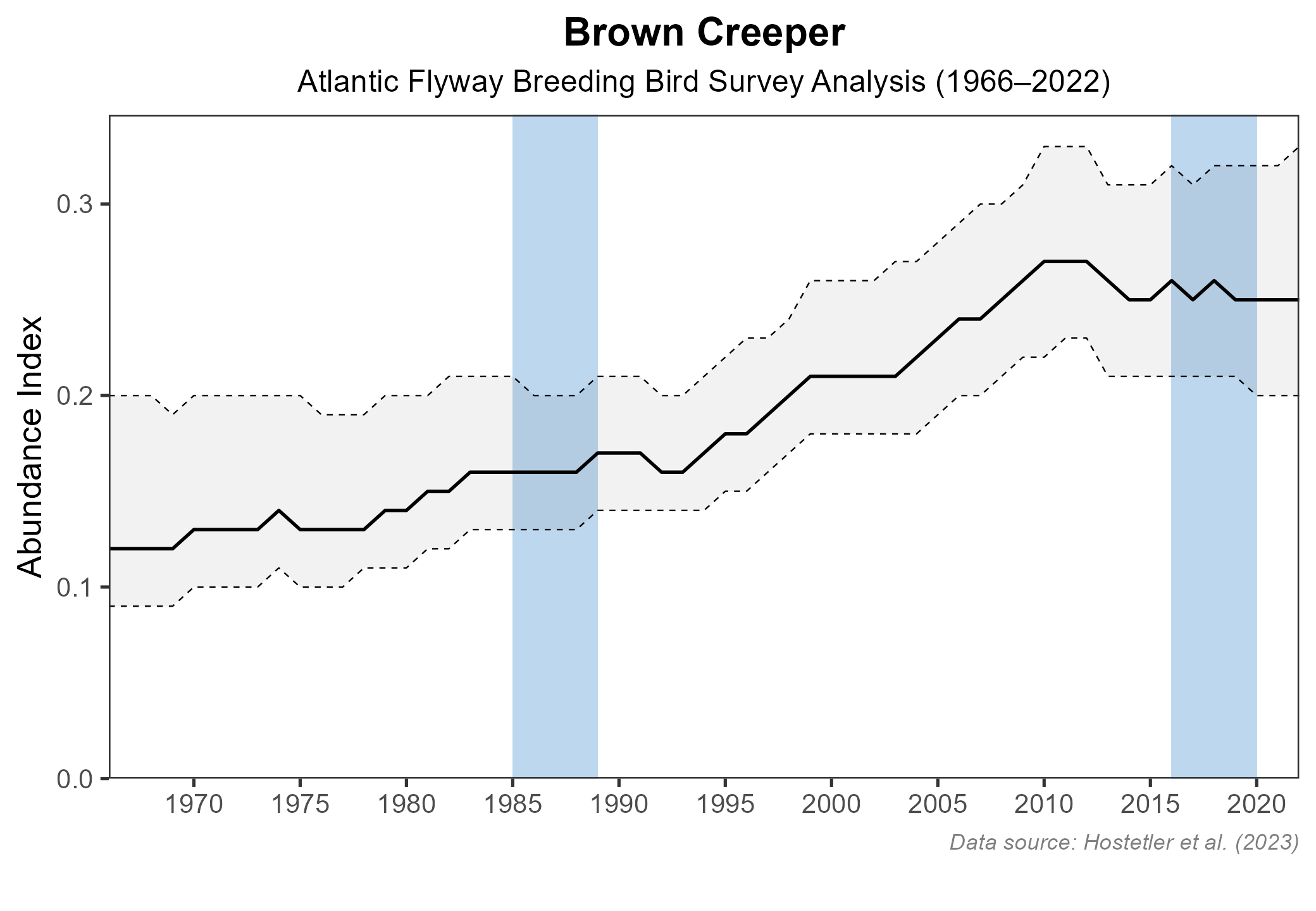

Due to limited detections during point count surveys, abundance models could not be run for the Brown Creeper, and North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) coverage in Virginia is limited. At the Atlantic Flyway scale, BBS data showed that the species experienced a significant increase of 1.28% per year from 1966–2022 Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 5). Between Atlas periods (1987–2018), the BBS trend for the Atlantic Flyway increased by a significant 1.53% per year.

Figure 5: Brown Creeper population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Although the Brown Creeper’s population appears to be increasing at the regional level, they remain rare in the state and rely on large trees, snags, and old-growth habitats that are under threat. However, to date, Brown Creepers do not appear to be declining due to these changes, but it is important to monitor them where they do occur.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Mays, R. S. (2006). Brown Creeper nesting in the mountains of Virginia. The Raven 77:3–12.

Poulin, J.-F., É. D’Astous, M.-A. Villard, S. J. Hejl, K. R. Newlon, M. E. McFadzen, J. S. Young, and C. K. Ghalambor (2020). Brown Creeper (Certhia americana), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole. Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.whbnut.01.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.