Introduction

The Blue-headed Vireo is distinct among Virginia’s vireos as the first to arrive in spring, last to depart in fall, and most likely to overwinter (Morton and James 2020; Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007). Virginia breeders belong to the Appalachian subspecies (Vireo solitarius alticola). This subspecies is a short-distance migrant, spending the winter from Virginia to the Gulf Coast (Morton and James 2020). The confiding and curious nature of the Blue-headed Vireo makes it a nice find in any season, though its breeding range in the mountains can be remote.

The males’ musical phrases echo pleasantly as they approach their partners on the nest in the wet hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) groves where they breed. This species was formerly known as the Solitary Vireo during the First Atlas, but between Atlases, the species was split into the Cassin’s Vireo (Vireo cassinii) on the Pacific Coast, Plumbeous Vireo (Vireo plumbeus) in the Rocky Mountains, and Blue-headed Vireo in the east (American Ornithologists’ Union 1997).

Breeding Distribution

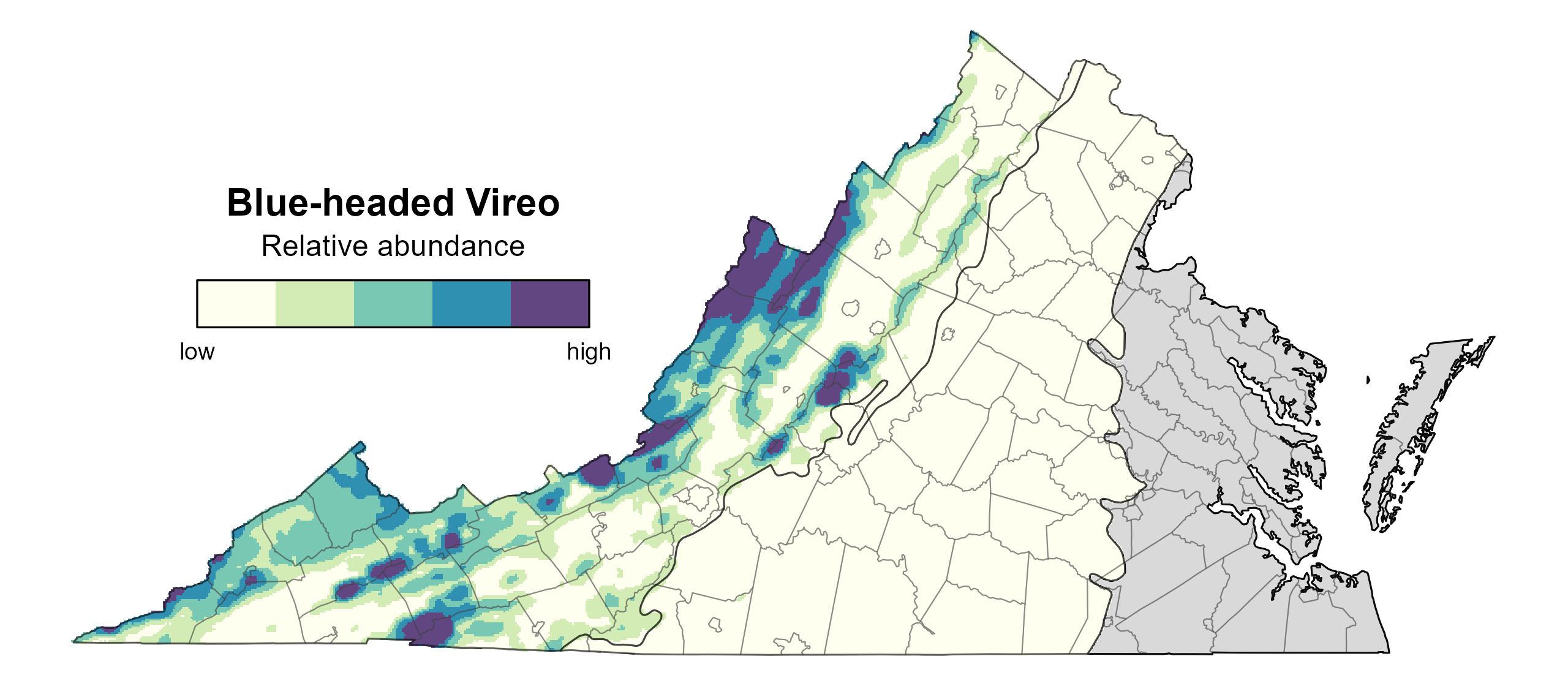

The Blue-headed Vireo is primarily a northern species, and its presence in Virginia represents a subspecies whose range extends south along the Appalachian Mountains. Its breeding is restricted to high-elevation habitats with mixed coniferous and deciduous forests. As such, Blue-headed Vireos occur primarily in the Mountains and Valleys region. They are most likely to occur in Bath and Highland Counties, as well as along the Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 1). The species is absent from the Shenandoah Valley and most areas of the Piedmont but do inhabit some sites there. The likelihood of Blue-headed Vireo occurrence increases sharply with elevation. Additionally, this species also is most likely to occur where there is a high proportion of forest cover in a block.

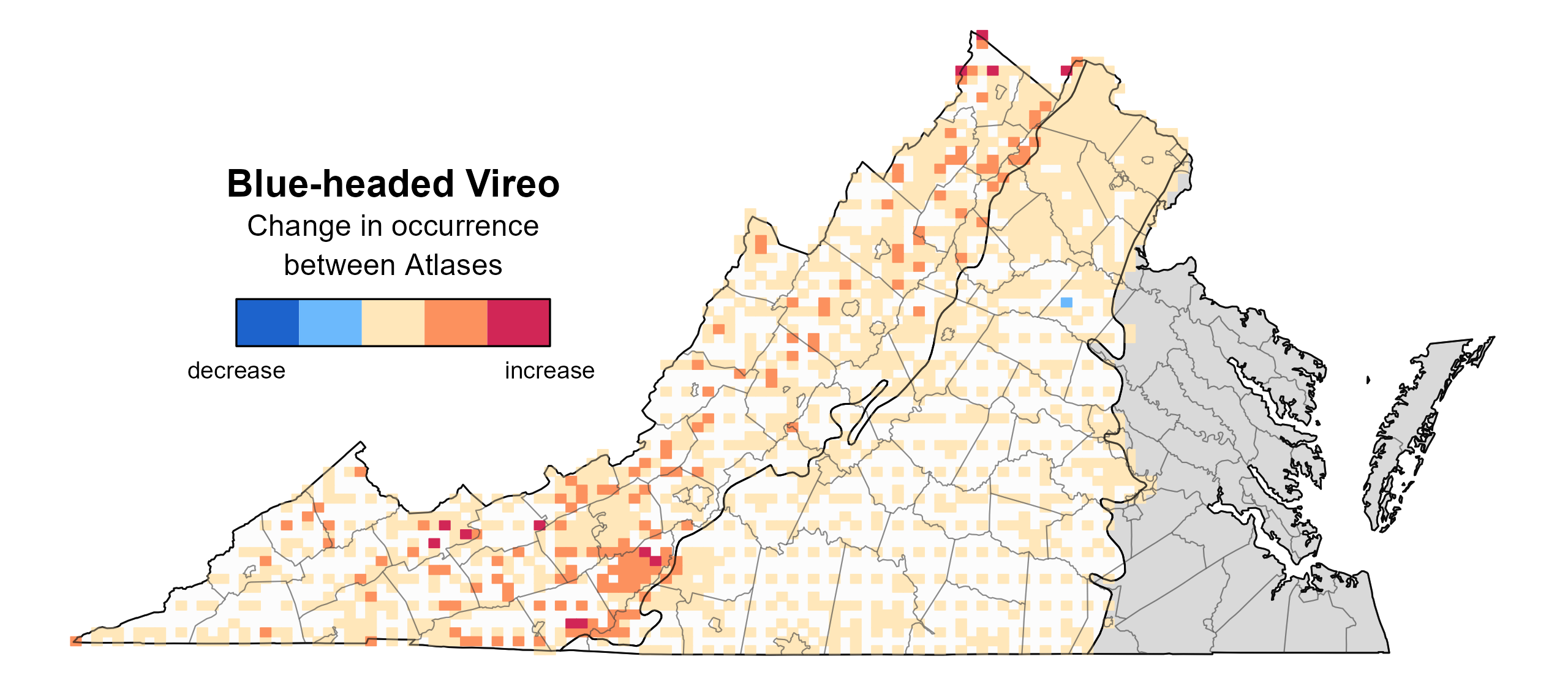

Between Atlas periods (Figures 1 and 2), the Blue-headed Vireo’s likelihood of occurrence increased throughout the Mountains and Valleys region, especially in the southern and northern portions (Figure 3). This increase is in line with its population increase in the state during this period (see Population Status).

View Environmental Associations

Figure 1: Blue-headed Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 2: Blue-headed Vireo breeding distribution based on probability of occurrence (First Atlas, 1985–1989). This map indicates the probability that this species will occur in an Atlas block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) based on environmental (including habitat) factors and after adjusting for the probability of detection (variation in survey effort among blocks). Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas and were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 3: Blue-headed Vireo change in breeding distribution between Atlases (1985–1989 and 2016–2020) based on probability of occurrence. This map indicates the change in the probability that this species will occur in a block (an approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey unit) between Atlas periods. Blocks with no change (tan) may have constant presence or constant absence. Blocks in white were not surveyed during the First Atlas so were not modeled. Blocks in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Breeding Evidence

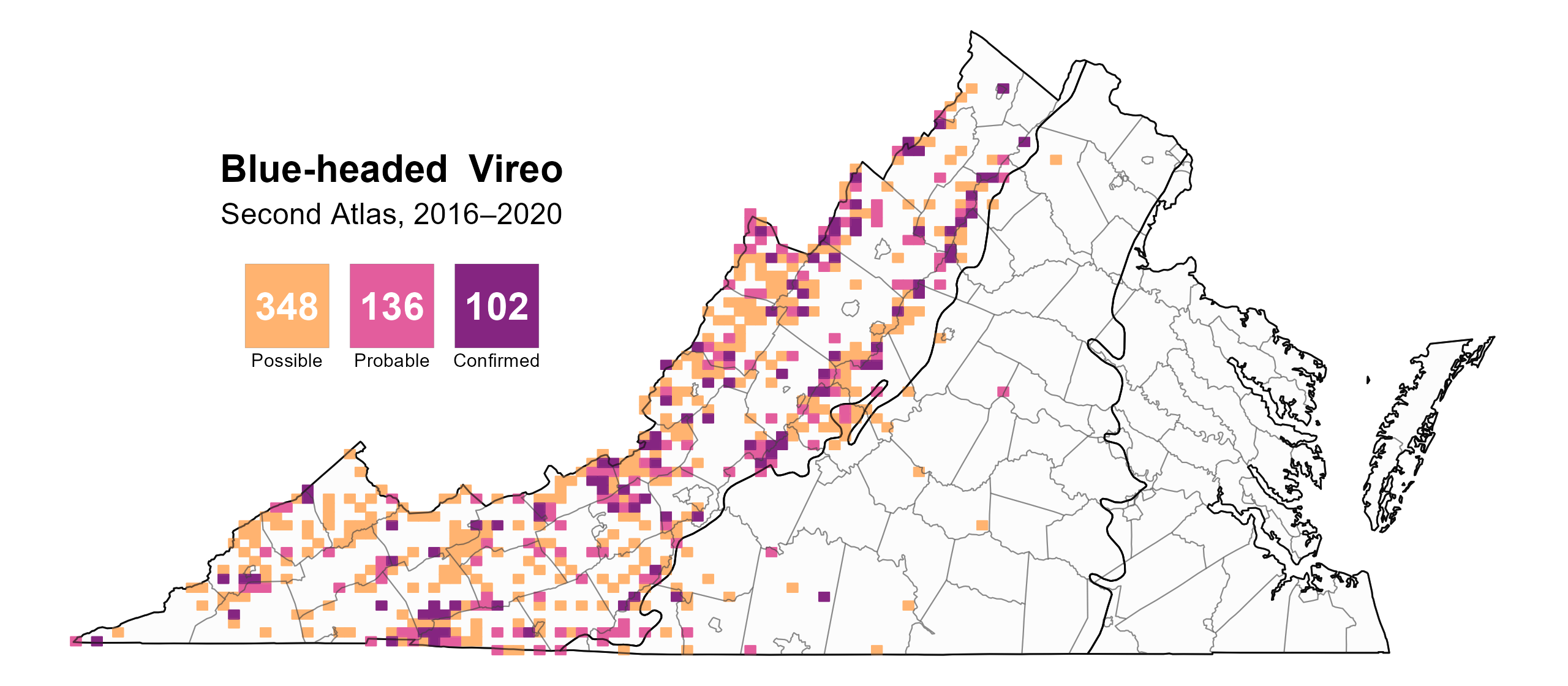

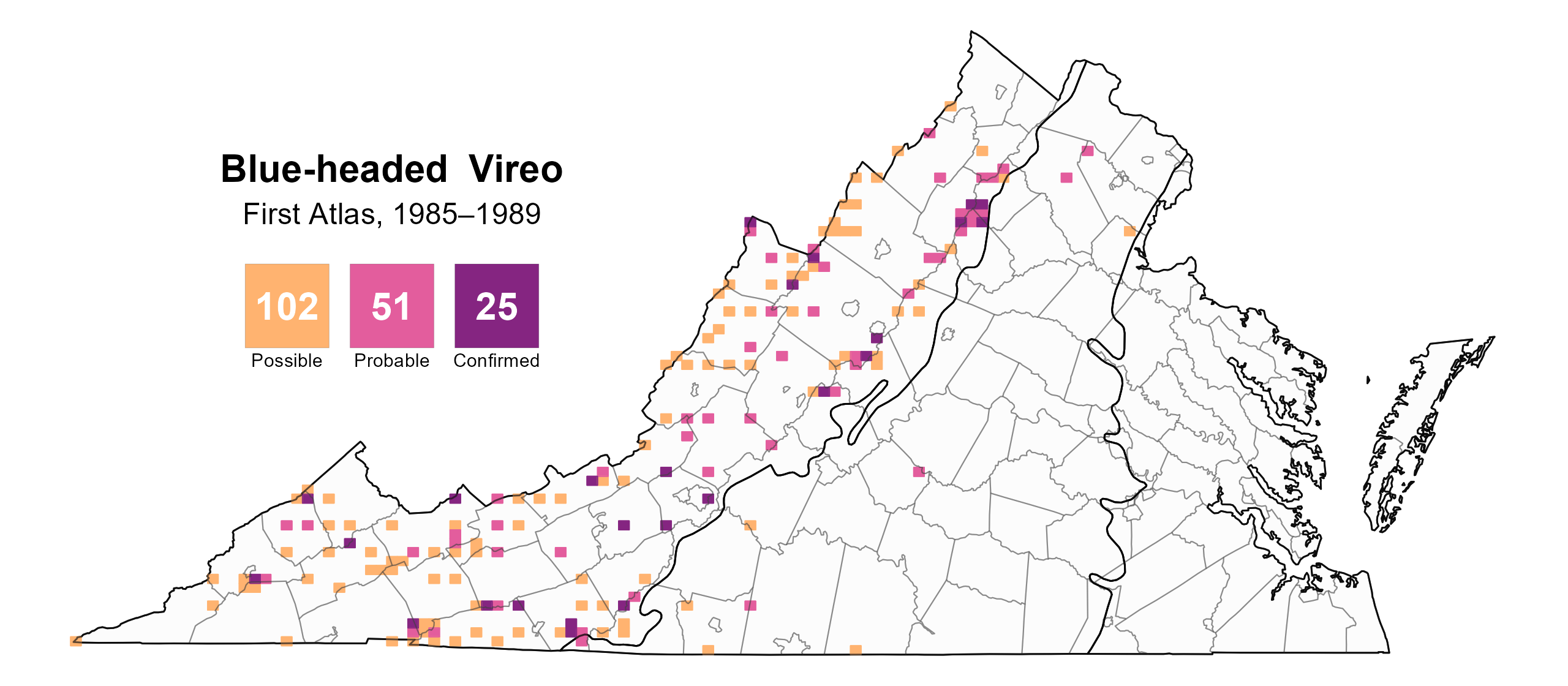

Blue-headed Vireos were confirmed breeders in 102 blocks and 39 counties, all primarily within the Mountains and Valleys region (Figure 4). In the southern Piedmont region, there were only two confirmations, including in Turkeycock Mountain Wildlife Management Area (Henry County) and near Elkhorn Lake (Pittsylvania County). During the First Atlas, breeding observations were recorded throughout the Mountains and Valleys region, although there were substantially fewer breeding records than during the Second Atlas, indicative of the species’ population growth within the state (see Population Status; Figures 4 and 5).

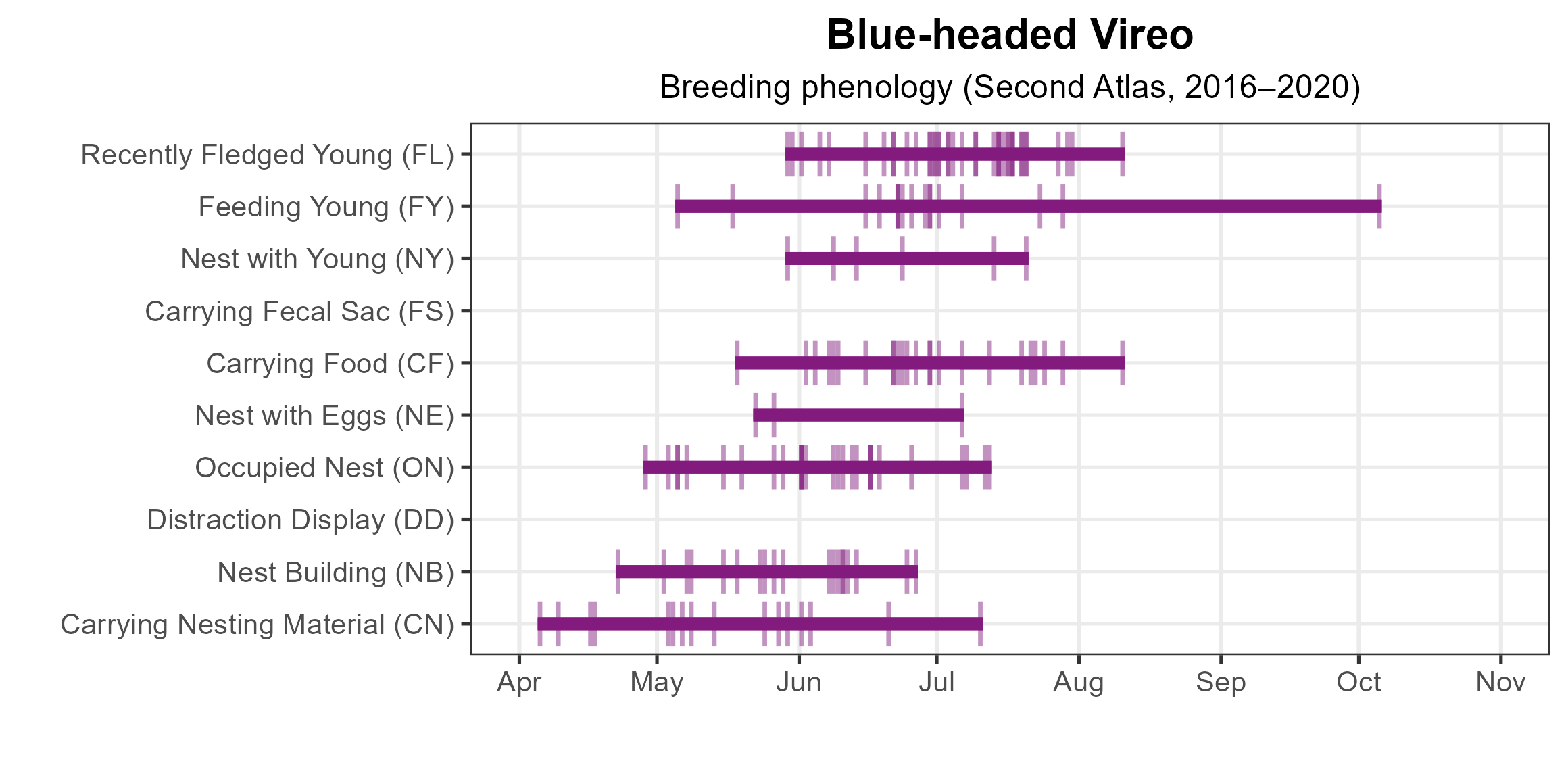

Many breeding confirmations came from occupied nests. Blue-headed Vireos are remarkably tame on the nest, and they can be easy to follow because the pairs switch parental duties so often (Morton 2003). Breeding was confirmed from April 5 (carrying nesting material) through mid-August, with an extreme late date of October 5, when an adult was seen feeding fledglings in Augusta County (Figure 6). The exceptionally late record is likely because the Appalachian population is commonly double-brooded, and females will desert their first broods when they fledge to start a second brood with a new mate (Morton and James 2020). For more general information on the breeding habits of the Blue-headed Vireo, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 4: Blue-headed Vireo breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 5: Blue-headed Vireo breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 6: Blue-headed Vireo phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Blue-headed Vireo relative abundance was estimated to be highest on slopes and ridges in the Mountains and Valleys region, specifically along the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains (Figure 7). Abundance was predicted to be particularly high in the vicinities of Mount Rogers and Whitetop Mountain (Grayson and Smyth Counties) and Mountain Lake (Giles County) and along the ridgeline at the West Virginia border in Highland and Rockingham Counties.

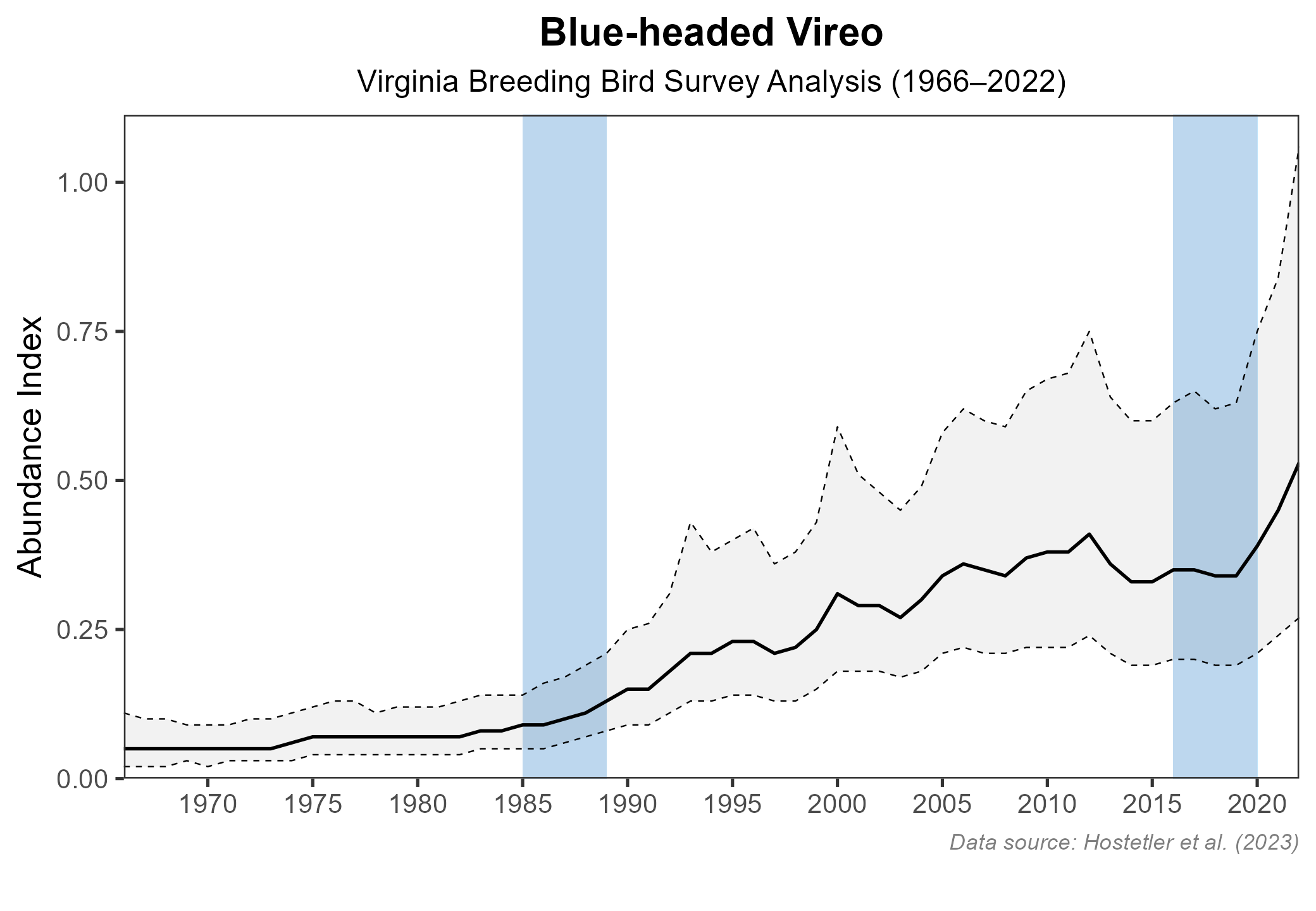

The total estimated Blue-headed Vireo population in the state is 153,000 individuals (with a range between 101,000 and 236,000). Population trends for the species are increasing in Virginia. Although its breeding habitat in Virginia is not always well-covered by the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), the species’ population experienced a significant increase of 4.37% per year from 1966–2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 8). Between Atlas periods, the BBS trend for Virginia was similarly positive, with a significant increase of 4.07% per year from 1987–2018.

Figure 7: Blue-headed Vireo relative abundance (Second Atlas, 2016–2020). This map indicates the predicted abundance of this species at a 0.4 mi2 (1 km2) scale based on environmental (including habitat) factors. Abundance values are presented on a relative scale of low to high. Areas in gray are outside the species’ core range and were not modeled.

Figure 8: Blue-headed Vireo population trend for Virginia as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

Because Blue-headed Vireo populations are increasing in the state, this species is not the focus of any conservation efforts in Virginia. As a family, vireos have done well over the past 60 years, with increasing populations in contrast to other songbirds such as warblers that are declining (Rosenberg et al. 2019).

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

American Ornithologists’ Union (1997). Forty-first supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union check-list of North American birds. The Auk 114: 542–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/4089270.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Morton, E. S. (2003). A migratory bird with sexual equality? Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/news/migratory-bird-sexual-equality.

Morton, E. S., and R. D. James (2020). Blue-headed Vireo (Vireo solitarius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.buhvir.01.

Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, et al. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366: 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: an annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.