Introduction

The sparrow-sized Black Rail is the smallest of the North American rails. In Virginia, it has been found in freshwater impoundments and wet meadows in pastures, although it is most at home in the large tidal saltwater marshes of the Eastern Shore (Watts 2016). There, the rail is associated with dense stands of salt meadow hay (Sporobolus pumilus) and salt grass (Distichlis spicata) with black needlerush (Juncus gerardii) (Wilson et al. 2007). Listening for their repeated kick-ee-kerr vocalization is the most reliable way to detect Black Rails (Eddleman et al. 2020). However, encounters with this secretive species are few and far between, as it may be the most the most imperiled bird along the Atlantic Coast (Wilson and Watts 2012).

Breeding Distribution

Within Virginia, the Black Rail’s currently known breeding distribution is confined to the Coastal Plain. However, given the species’ highly secretive nature and its rarity in the Commonwealth, only three records were reported by Atlas volunteers; thus, no distribution models could be developed. For more information on the distribution of this species, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

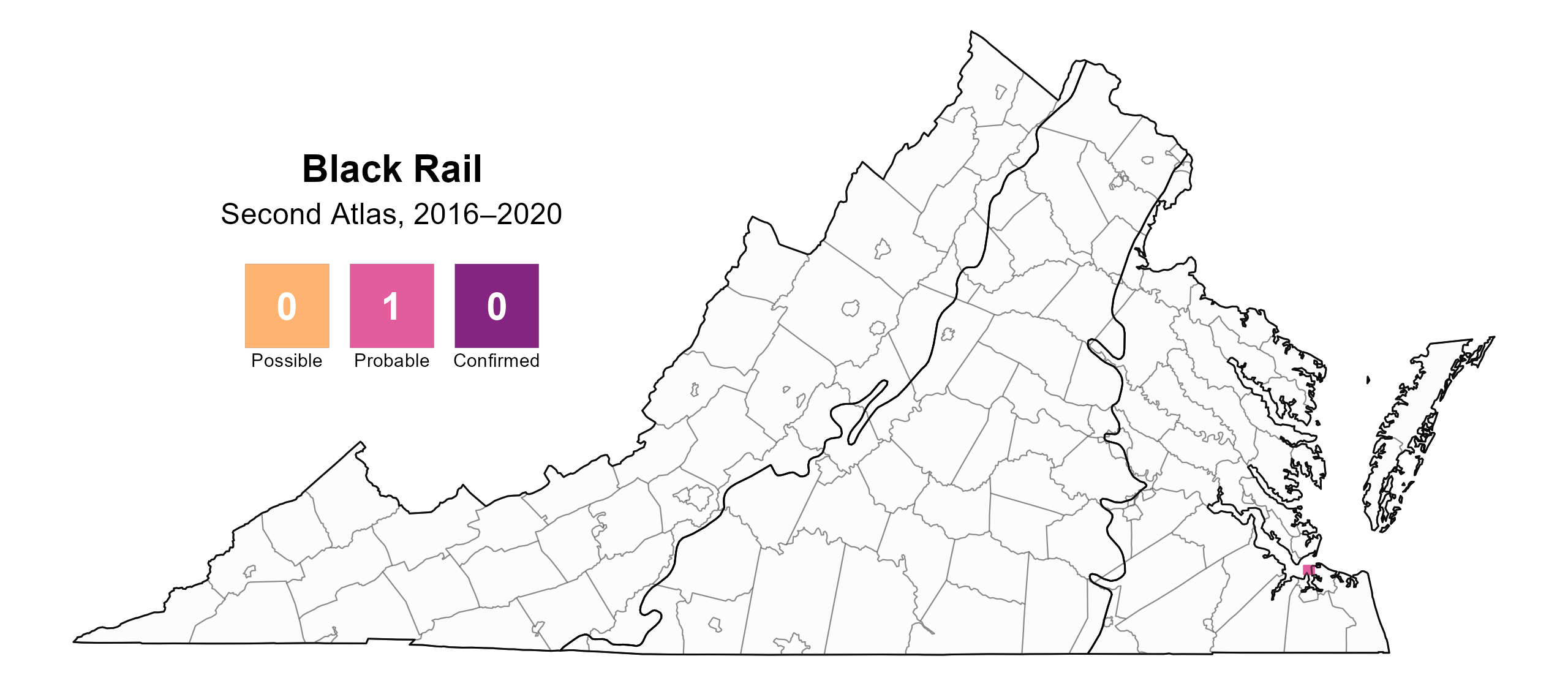

Volunteers documented just one potential breeding location for the species in Portsmouth, where it was classified as a probable breeder. At this site, a male was heard calling in appropriate breeding habitat during three visits between June 22 and July 7, 2017 (Figure 1). The Black Rail was documented in only two Coastal Plain blocks during the First Atlas, including in the Saxis Marsh area (Accomack County), once a stronghold for the species (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Black Rail breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Black Rail breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Population Status

Given that Black Rails were not detected on point count surveys, no abundance model could be developed. However, the Virginia population is estimated to be as low as 10 breeding pairs (Watts 2016). Wilson and Turrin (2014) noted that Black Rail populations in the Chesapeake Bay have declined by more than 85% or more since the late 1990s, reaching dangerously low levels.

Conservation

Due to dramatic population declines across its eastern breeding range, the eastern subspecies of the Black Rail (L. jamaicensis jamaicensis) was listed as federally threatened in 2020. Given its extremely small and dwindling population in the Commonwealth, the species is listed as state endangered in Virginia and is classified as a Tier I (Critical Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025).

The Virginia Black Rail population is in a precarious position. Over the years, the species has been documented in the inner Coastal Plain and at locations in the Piedmont and Mountain and Valleys regions (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007; Watts 2016). However, saltwater marshes from Dorchester County in Maryland through Accomack County in Virginia were historically considered the stronghold for the entire Mid-Atlantic Black Rail population (Wilson et al. 2015). A 2007 systematic survey for the species on Virginia’s Eastern Shore found only 15 individuals (Wilson et al. 2009), with follow-up surveys in 2014 detecting only two individuals (Wilson et al. 2015). As of 2023, there were only two documented occurrences in Accomack County (Bryan Watts, personal communication). Black Rails are difficult to detect, and there is a lack of consistent survey effort in the extensive marshes on the seaside of Accomack County (Watts 2016); thus, there may be undocumented occurrences of the species. Regardless, the population is likely to be at very low levels and may be at risk of extirpation in Virginia (Wilson and Watts 2012).

Black Rails face several threats, but the reasons for their decline are not well understood. Degradation and loss of marsh habitat may have contributed in the past but are unlikely the current factors limiting Black Rails in Virginia, as there is much available habitat on the Eastern Shore that is not occupied (Wilson and Watts 2012). Nest failure because of predation is another possibility. Within tidal marshes, Black Rails nest in higher areas of the marsh adjacent to upland habitat, which tend not to be flooded by tidal waters (Wilson et al. 2009). This scenario makes them vulnerable to nest predators such as red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), raccoons (Procyon lotor), and cats (Felis catus). An experimental study in Accomack County using artificial nests in fact found low nest success rates, with average depredation occurring within half the length of time required for incubation by Black Rails (Wilson and Watts 2014). Loss of marshes to sea-level rise and marsh degradation through invasion by common reed (Phragmites australis) are also potential factors contributing to Black Rail declines in Virginia (Watts 2016).

More recently, under the jurisdiction of the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (ACJV), an Eastern Black Rail Working Group led by the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary has laid much of the groundwork for Black Rail conservation. The rail is one of three flagship species of the ACJV, which has finalized a Black Rail Conservation Plan (ACJV 2020). The Plan promotes creation and management of nontidal habitat and development of practices to facilitate marsh migration into upland areas to counter the effect of marsh loss to sea-level rise. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources is implementing some of these recommendations in two of its Wildlife Management Areas (WMA) on the Eastern Shore. They include control of common reed and marsh restoration at two impoundments to enhance habitat for Black Rail. It is hoped that the impoundment work at Doe Creek WMA can serve as a model for similar efforts at other coastal WMAs and at privately-owned impoundments.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (ACJV) 2020. Eastern Black Rail conservation plan for the Atlantic Coast. www.acjv.org.

Eddleman, W. R., R. E. Flores, and M. Legare (2020). Black Rail (Laterallus jamaicensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blkrai.01.

Rottenborn, Stephen C, and Edward S Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s Birdlife: An Annotated Checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D. 2016. Status and distribution of the Eastern Black Rail along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of North America. The Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-16-09. College of William and Mar and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 148 pp.

Wilson, M. D., B. D. Watts and D. F. Brinker. 2007. Status review of Chesapeake Bay marsh lands and breeding marsh birds. Waterbirds 30(sp1):122–137.

Wilson, M. D., B. D. Watts, and F. M. Smith. 2009. Status and distribution of Black Rails in Virginia. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-0-010. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, USA. 22 pp.

Wilson, M. D. and B. D. Watts. 2012. The Virginia avian heritage project: a report to summarize the Virginia avian heritage database. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-12-04. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, UVA. 48 pp.

Wilson, M. D. and B. D. Watts. 2014. Nesting potential of high marsh nesting birds in tidal marshes of Virginia Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-14-006. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University. Williamsburg, VA, UVA. 13 pp.

Wilson, M. D. and C. Turrin. 2014. Assessing the role of marsh habitat change on the distribution and decline of Black Rails in Virginia. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-14-009. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, UVA. 14 pp.

Wilson, M. D., F. M. Smith, and B. D. Watts. 2015. Re-Survey and population status update of the Black Rail in Virginia. The Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-15-04. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA, UVA. 14 pp.