Introduction

Virginia’s smallest swallow, the Bank Swallow is often seen feeding on flying insects over water. Although it can mix with other foraging swallows in a blur of constant motion, the attentive observer can distinguish the Bank Swallow by the brown band across its otherwise white breast. Its scientific name means “of the riverbank” and describes the Bank Swallow’s association with vertical banks and bluffs along lakes and rivers, where they nest in burrows that are excavated mostly by the male using its bill, feet, and wings (Garrison and Turner 2020). In the eastern U. S., including Virginia, the species also nests in sand and gravel quarries (Garrison and Turner 2020). Bank Swallows colonies can range from a dozen to hundreds of breeding pairs (Garrison and Turner 2020).

Breeding Distribution

Virginia lies toward the southern end of the Bank Swallow’s eastern breeding distribution in North America. Data limitations prevented development of a robust distribution model for the species based on data from the Second Atlas. Please see the Breeding Evidence section for more information on breeding distribution.

Breeding Evidence

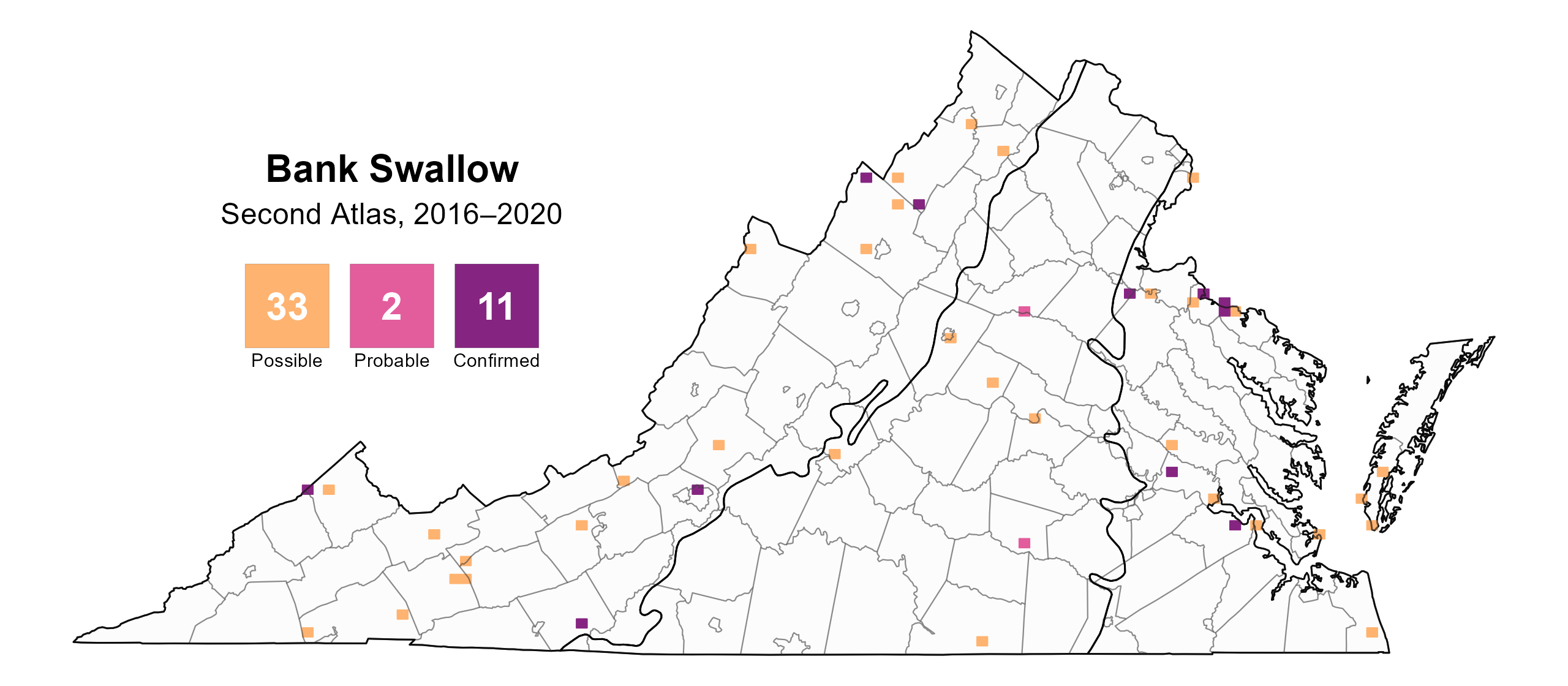

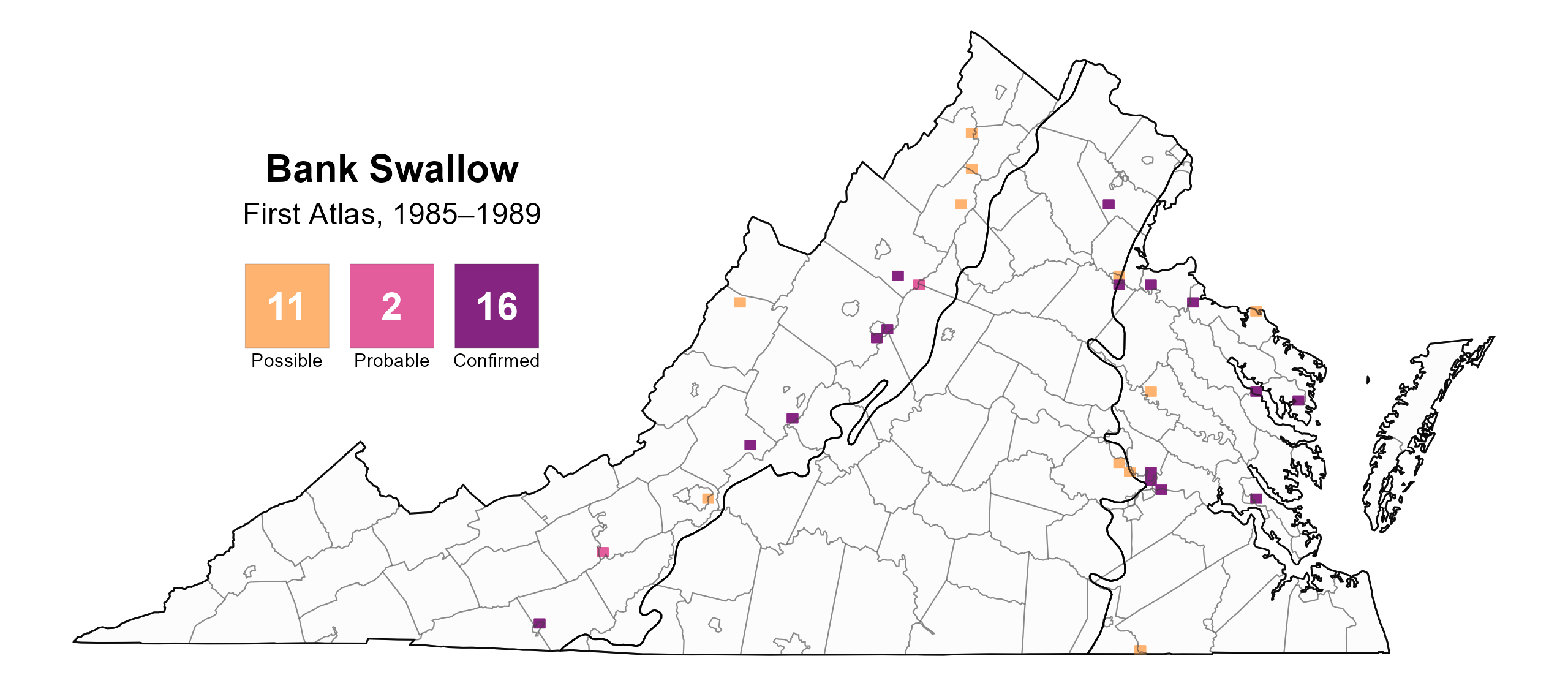

Bank Swallows were confirmed breeders in 11 blocks and nine counties in the Coastal Plain and Mountains and Valleys (Buchanan, Carroll, Charles City, Roanoke, Rockingham, Shenandoah, Spotsylvania, Surry, and Westmoreland). These areas ranged from cliff sites along the Potomac and James Rivers to inland sand and gravel operations (Figure 1). They were found to be probable breeders in two additional counties in the Piedmont region (Nottoway and Orange). The number of blocks in which Bank Swallows were reported rose by nearly 60% from the First Atlas to the Second Atlas (Figures 1 and 2); however, it is possible these additional detections were due to greater survey effort in the Second Atlas.

Breeding was primarily confirmed through observations of nests (May 15 – June 23), with recently fledged young observed on June 24 and 25 (Figure 3).

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Bank Swallow breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Bank Swallow breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Bank Swallow phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

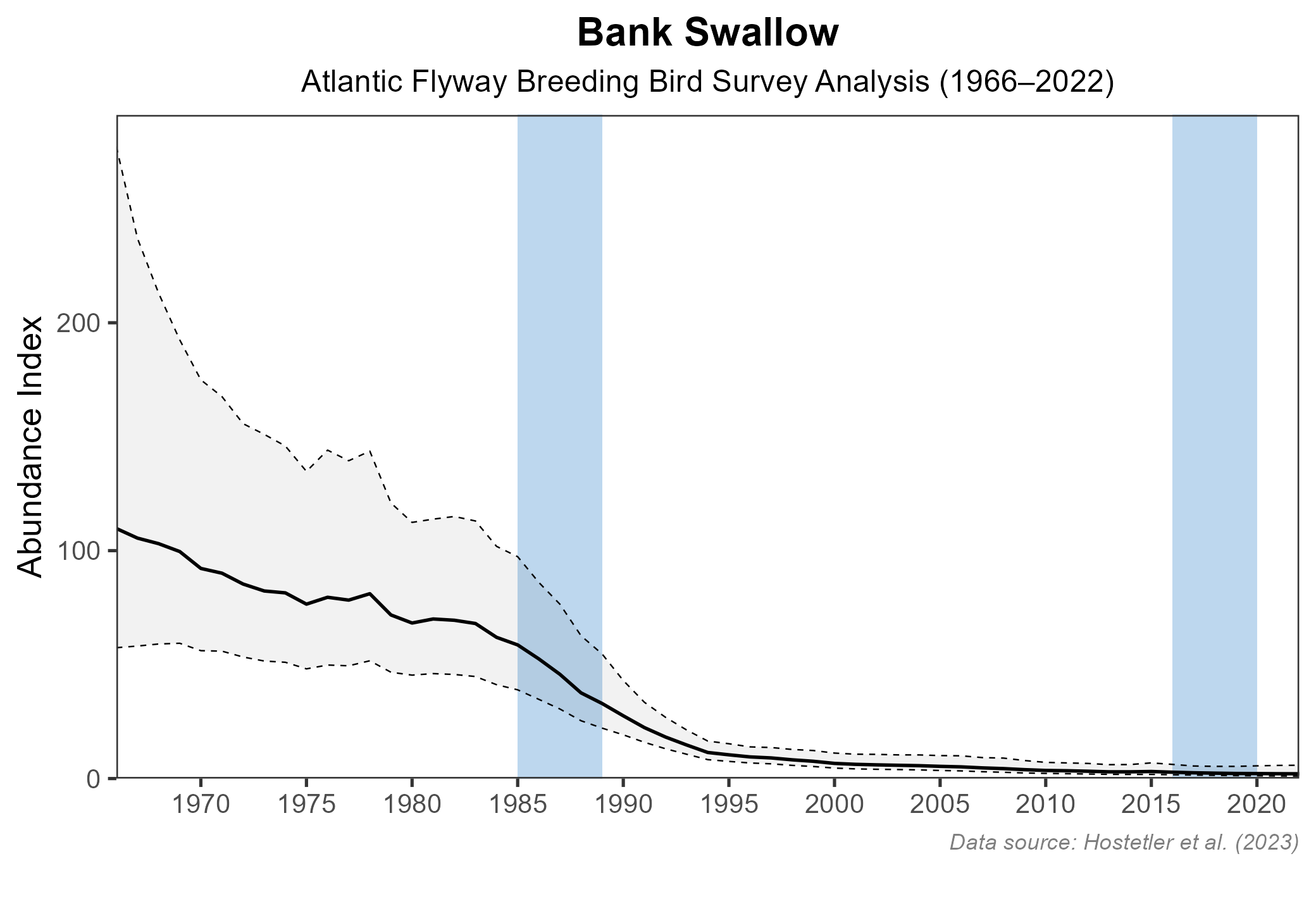

Bank Swallows were only detected at one point during the Atlas point count surveys; thus, it was not possible to develop an abundance model for the species. A credible population trend for Virginia, where the species was detected on only ten routes, could not be estimated through the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). However, the Atlantic Flyway BBS trend indicated a significant annual decline of 6.79% between 1966 and 2022 (Hostetler et al. 2023; Figure 4); at a significant 9.08% decline per year, the trend between Atlas periods (1987–2018) was even steeper.

Figure 4: Bank Swallow population trend for the Atlantic Flyway as estimated by the North American Breeding Bird Survey. The vertical axis shows species abundance; the horizontal axis shows the year. The solid line indicates the estimated population trend; there is a 97.5% probability that the true population trend falls between the dashed lines. The shaded bars indicate the First and Second Atlas periods.

Conservation

The Bank Swallow is classified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Tier III: High Conservation Need) in the 2025 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan based on its ongoing decline within the Commonwealth (VDWR 2025).

The species’ use of naturally occurring cliffs, banks, and bluffs along rivers within Virginia’s Coastal Plain region may be limited. In the mid-1990s, the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) at the College of William and Mary conducted a systematic survey of exposed banks along 900 Chesapeake Bay tributaries. They found Bank Swallows in fewer than 20 locations, clustered on the upper Eastern Shore of Maryland, in breeding colonies of up to 500 burrows. Only one Virginia colony, numbering 49 pairs, was documented in the vicinity of Presquile National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) on the James River in Chesterfield County (Bryan Watts, unpublished data). Historically, colonies were known from the Potomac, Rappahannock, and James Rivers (Bryan Watts, personal communication).

The dynamic nature of shoreline habitats, shoreline development, and human modifications to shorelines for erosion control have likely contributed to their reduced use by Bank Swallows. Blem and Blem (1990) documented the decline in the previously mentioned colony site near Presquile NWR between 1975 (when it numbered over 430 burrows) and 1989 due to slumping of the steep bank, which originally was the byproduct of excavating a shipping channel. This slumping contributed to a loss of the softer substrate needed by the birds to excavate their burrows. Some movement of the displaced birds to nearby quarries was noted (Blem and Blem 1990) and use of sand pits was also documented during the CCB Chesapeake Bay surveys and in a 2022 survey of quarries (Bryan Watts, unpublished data). This adaptability has probably helped Bank Swallows to persist in the Commonwealth. In addition, breeding documented in several western counties along rivers (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007) and streams highlights the importance of inland sites to the species in Virginia.

Although the Atlas provides valuable data on the distribution of Bank Swallows, additional information on both its distribution and habitat use is needed as a starting point for conservation efforts. This research could include systematic surveys of rivers and streams with potentially suitable habitat, as well as surveys of human-made sites such as quarries and sand pits. However, the conservation of Bank Swallows may be challenged by the ephemeral nature of their colony sites, with larger colonies having a greater chance of persisting over time than smaller colonies (Garrison and Turner 2020). Identifying sites with high usage, if any exist, is therefore a priority. Due to its migratory nature, the Bank Swallow may also be vulnerable to threats on its wintering grounds in South America; better information on where Virginia’s birds migrate is needed to assess potential threats.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Blem, C. R., and L. B. Blem (1990). Bank Swallows at Presquile National Wildlife Refuge: 1975-1989. The Raven 61:3-6.

Garrison, B. A., and A. Turner (2020). Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.banswa.01.

Hostetler, J. A., J. R. Sauer, J. E. Hines, D. Ziolkowski, and M. Lutmerding (2023). The North American breeding bird survey, analysis results 1966–2022. U.S. Geological Survey, Laurel, MD, USA. https://doi.org/10.5066/P9SC7T11.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.