Introduction

Flaking pieces of bark raining from a loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) may be a good indication of a foraging Red-cockaded Woodpecker, if you find yourself in the right habitat. The Red-cockaded Woodpecker is emblematic of mature southeastern pine savannas, fire-maintained woodlands with a diverse, open understory, within which it is a year-round resident. It is unique among North American woodpeckers in being the only species that excavates its cavities nearly exclusively in living pine trees (USFWS 2003), which are often infected by red heart fungus (Phellinus pini), and must reach a certain girth to accommodate a cavity. Cavity excavation can be a long process that can require years to complete (Harding and Walters 2004).

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker is also one of three percent of the bird species worldwide with a cooperative breeding system, with mature individuals deferring reproduction and assisting a breeding pair, to whom they are often related, in raising young. The woodpeckers live in family groups known as “potential breeding groups,” which consist of a breeding pair with or without one or more helpers.

Steep population declines stemming from extensive, range-wide habitat loss resulted in the Red-cockaded Woodpecker being one of the earliest species to be protected under the federal Endangered Species Act. Today, a healthy population in Virginia continues to expand with the assistance of dedicated conservation actions (Hines et al. 2024). The white paint bands used by managers to mark trees with cavities and the wavering seep calls of the species as it emerges from its cavities at dawn indicate the success of these efforts.

Breeding Distribution

Virginia boasts the northernmost population of Red-cockaded Woodpeckers. Because the species is restricted to only two locations in the Commonwealth, its distribution could not be modeled. For information on where Red-cockaded Woodpeckers occur in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

Red-cockaded Woodpeckers were confirmed breeders in four blocks in two counties (Figure 1). They are currently known from two sites in Virginia: in Sussex County at Piney Grove Preserve and the adjacent Big Woods Wildlife Management Area (WMA) and in Chesapeake at the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), close to the border with North Carolina. The first individual Red-cockaded Woodpecker to be documented at Big Woods WMA was in 2016, the first year of the Second Atlas (Sergio Harding, personal communication). Intensive management to open the understory has improved habitat at this site, with the goal of hosting many more breeding Red-cockaded Woodpeckers.

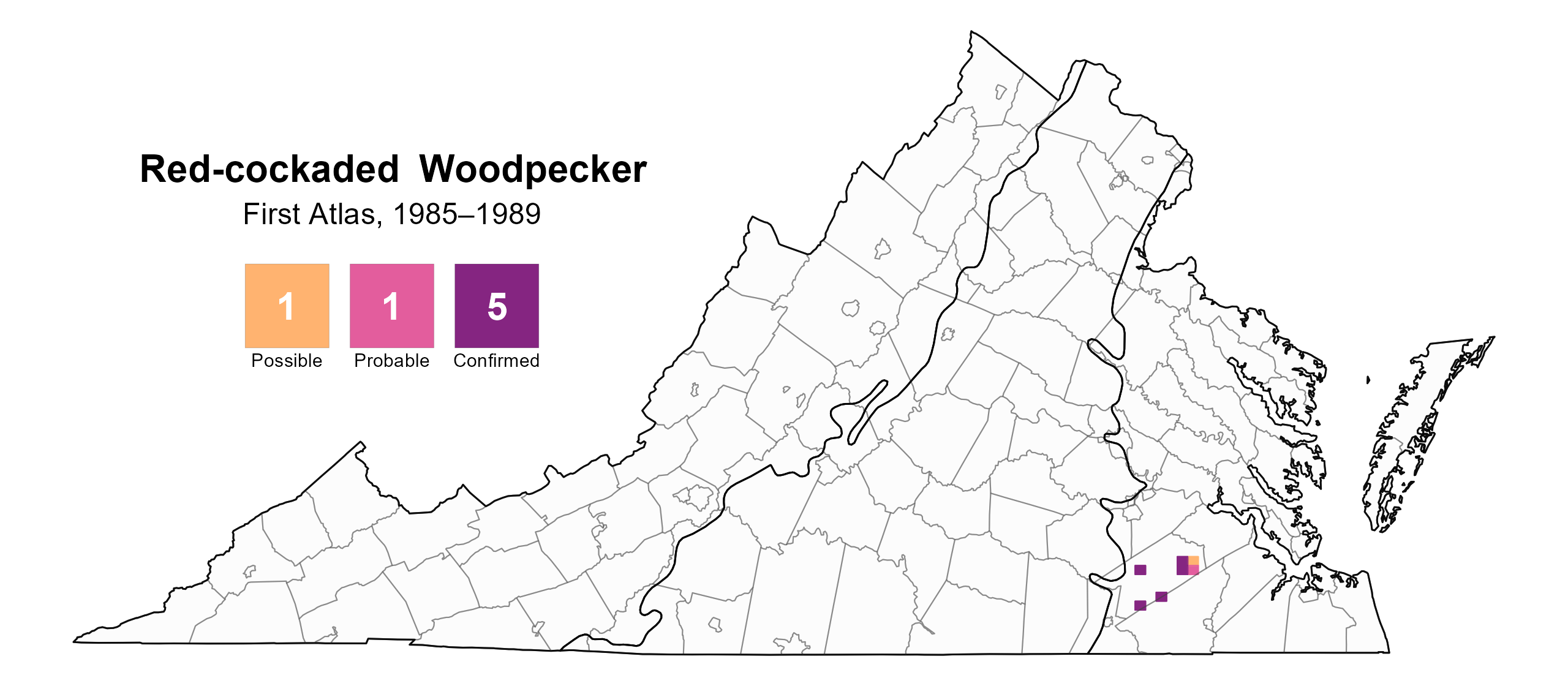

The historic range of Red-cockaded Woodpecker in Virginia likely matched the historic distribution of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) savannas (Watts and Bradshaw 2004), which were primarily found south of the James River in early colonial times. However, historic records of the species are known from as far west as Lee (Rottenborn and Brinkley 2007) and Giles (Bailey 1913) counties and as far north as Albemarle County (Rives 1890). By the time of the First Atlas, they were only known as breeders at a few locations in Sussex County (Figure 2). Further declines reduced the known population to a low of just two breeding pairs at Piney Grove in 2002. Between Atlas periods, intensive management has boosted their populations, and they have expanded to new sites.

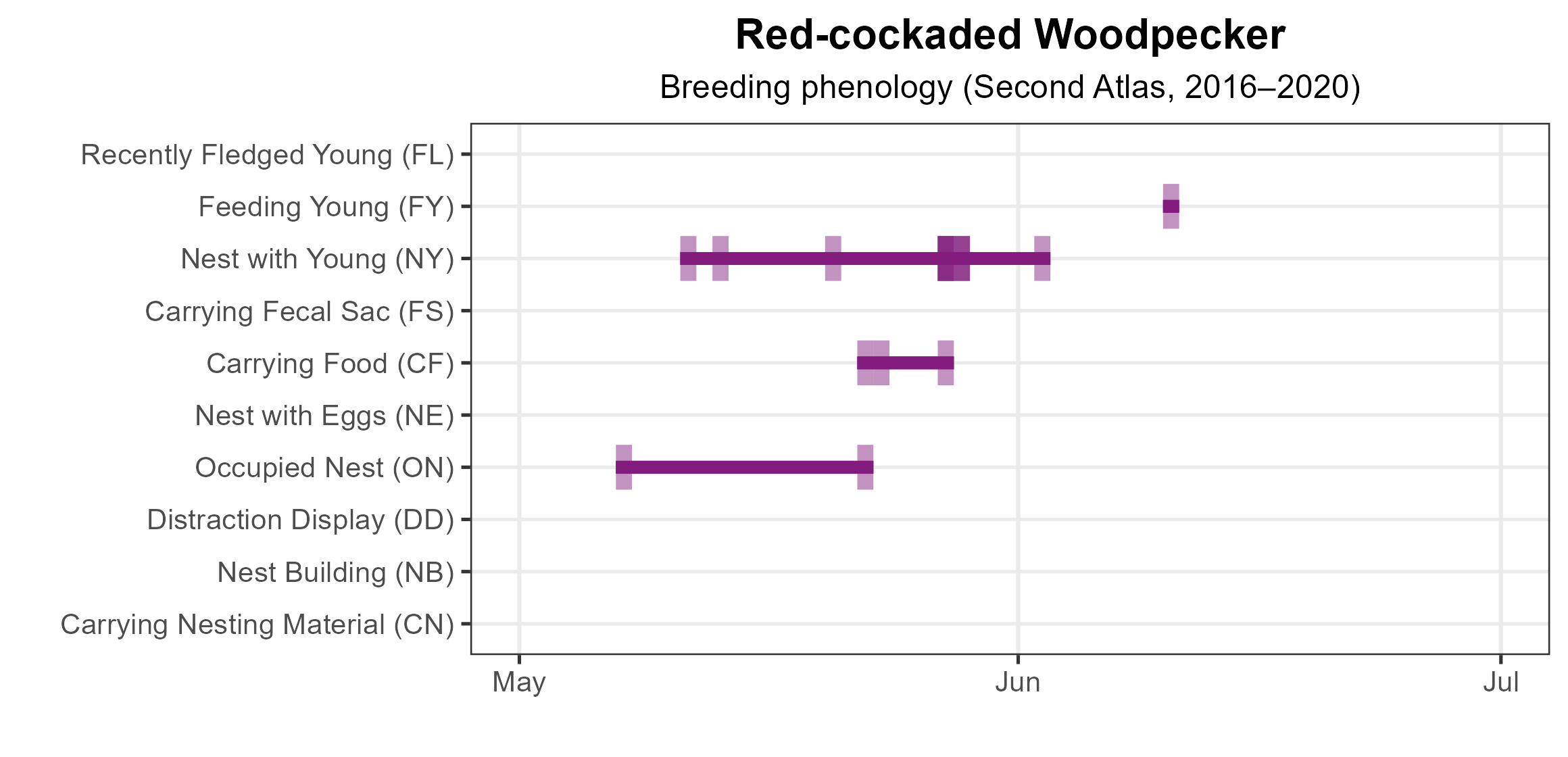

Because Atlas observers seldomly had access to the species and because they nest in cavities, information on their breeding phenology is limited. Atlas volunteers documented occupied nests starting from May 7, with adults seen feeding young through June 10 (Figure 3). The true distribution of breeding behaviors likely extends earlier and later than these dates, but because there are so few birds and most are not in publicly accessible areas, there was a small sample size. Researchers use dedicated tools to observe activity inside the cavity, such as telescoping poles with cameras to count eggs and nestlings. For more general information on the breeding habits of the Red-cockaded Woodpecker, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Red-cockaded Woodpecker breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Red-cockaded Woodpecker breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Red-cockaded Woodpecker phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Atlas point count surveys were not conducted in areas where Red-cockaded Woodpeckers are known to occur, so an abundance model could not be produced for the species. Similarly, the species does not occur along any North American Breeding Bird Survey routes in Virginia; thus, no trend could be estimated from these surveys. Monitoring of the Piney Grove population, however, provides annual censuses of the number of breeding groups and individuals. In 2024, the site supported 21 potential breeding groups and 135 individual woodpeckers (including 35 fledged young). These numbers are testament to a growing population, which at its lowest consisted of only two potential breeding groups in 2002 (Hines et al. 2024).

Conservation

The range wide decline in the Red-cockaded Woodpecker was caused by the almost complete loss of the old growth, fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas that once dominated the southeastern U.S. and upon which the species depends (USFWS 2003). Intensive logging for lumber and agriculture in the 1800s, followed by fire suppression in the 1900s, resulted in scattered, isolated, and declining populations of the woodpecker (USFWS 2003), including a small remnant population in Virginia. This Virginia population saw further declines due to timber harvests between 1980 and 2000 (Watts and Bradshaw 2004).

As a federally listed species, the Red-cockaded Woodpecker has benefitted from decades of study on its ecology, which have led to detailed population and habitat management prescriptions and a National Recovery Plan (USFWS 2003). Implementation of the Plan’s guidance across the species’ range has resulted in significant progress toward the Plan’s population goals, leading to the downlisting of the woodpecker from federally endangered to threatened status in October 2024. The species remains listed as endangered at the state level in Virginia, however, given its small population size and its concentration in mostly one geographic area in Sussex County, making it vulnerable to storm and weather events that could cause blowdowns of the pines that the Red-cockaded Woodpecker depends on, which could be catastrophic for the Virginia population. For these reasons, the species is also classified as a Tier I (Critical Conservation Need) Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2025 Wildlife Action Plan (VDWR 2025).

Despite this vulnerability, recovery efforts for the species in Virginia have been greatly successful. Aggressive habitat management at Piney Grove Preserve by The Nature Conservancy and partners, coupled with cavity management, creation of artificial cavities, and intensive banding and population monitoring by the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary have brought the Red-cockaded Woodpecker back from the brink of extirpation to a now thriving and slowly expanding population. Acquisition of the abutting Big Woods WMA by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) in 2011 and management of the property for mature pine savanna resulted in establishment of a pair on the WMA in 2019. The WMA will continue to provide much needed habitat to accommodate the needs of the growing Piney Grove Preserve population.

Recovery efforts on the Preserve were aided in earlier years through translocation of Red-cockaded Woodpeckers from a stable population in South Carolina (Watts and Harding 2007). Translocations also took place into Great Dismal Swamp NWR between 2015 and 2021 and were successful in establishing a few potential breeding groups there. Additional resources will need to be invested into properly monitoring and growing this ancillary population, if it is to persist into the future.

With its small Red-cockaded Woodpecker population, Virginia currently plays a modest role in range-wide recovery efforts for the species. However, if the species’ core range creeps northward due to climate-induced habitat changes, the Commonwealth may be positioned to provide critical habitat to accommodate that shift and could become more central to the species’ national story.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Bailey, H. H. (1913). The birds of Virginia. J.P. Bell Company, Incorporated, Lynchburg, VA, USA.

Harding, S.R., and J.R. Walters (2004). Dynamics of cavity excavation by Red-cockaded Woodpeckers. In Red-cockaded woodpecker: road to recovery (R. Costa and S. J. Daniels, Editors). Hancock House Publishers, Blain, WA, USA.

Hines, C., L. Duval, B. D. Watts, and B. J. Paxton (2024). Investigation of Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in Virginia: year 2024 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-24-13. William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 37 pp.

Rives, W. C. (1890). A catalogue of the birds of the Virginias. Proceedings of the Newport Natural History Society. Newport, RI, USA.

Rottenborn, S. C., and E. S. Brinkley (Editors) (2007). Virginia’s birdlife: An annotated checklist. 4th edition. Virginia Society of Ornithology.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2003). Recovery plan for the Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis): second revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, GA, USA. 296 pp.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR) (2025). Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.

Watts, B. D., and D. S. Bradshaw (2005). Decline and protection of the Virginia Red-cockaded Woodpecker population. In Red-cockaded Woodpecker: road to recovery (R. Costa and S. J. Daniels, Editors). Hancock House Publishers, Blain, WA, USA.

Watts, B.D. and S. R. Harding. 2007. Virginia Red-cockaded Woodpecker conservation plan. CCBTR-07-07. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, USA. 42 pp.