Introduction

The Piping Plover is a dapper bird of serene Atlantic beaches, where it can be seen foraging for invertebrates at or below the high-tide wrack line. If you draw too close, adults may perform a “broken wing display”, wherein they feign injury to lure you, a potential predator, away from their nest. Less noticeable than this display are the plover’s speckled tan eggs, which sit perfectly camouflaged in a small scrape in the sand often lined with tiny pieces of shell.

The Atlantic Coast population was listed as federally threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1986, just as the First Atlas began. Since then, coordinated monitoring and protection across much of its range, including Virginia, have led to partial recovery, but gains remain fragile. Reproductive success has faltered in recent years, and future habitat loss from sea-level rise could reverse decades of progress.

Breeding Distribution

Because the species is rare, its occurrence could not be modeled. For information on where Piping Plovers occur in Virginia, please see the Breeding Evidence section.

Breeding Evidence

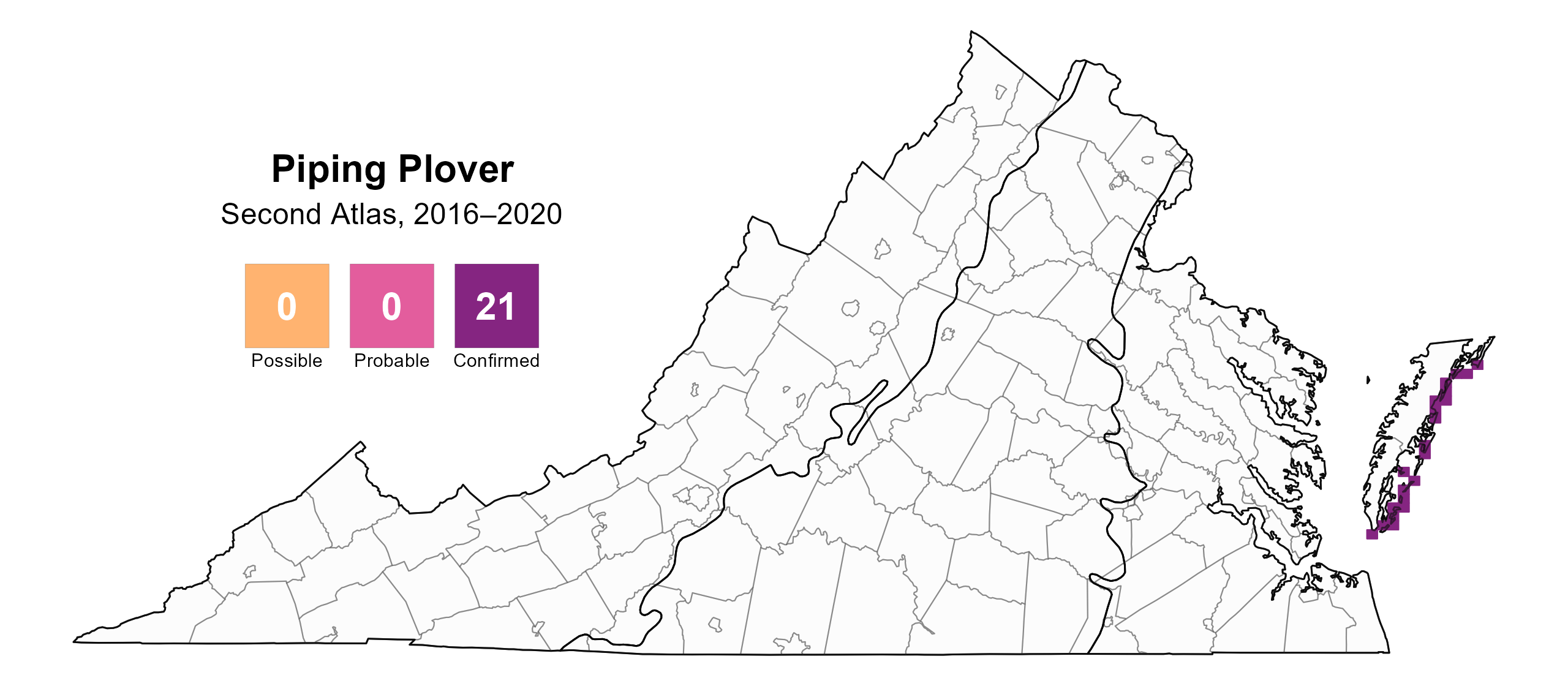

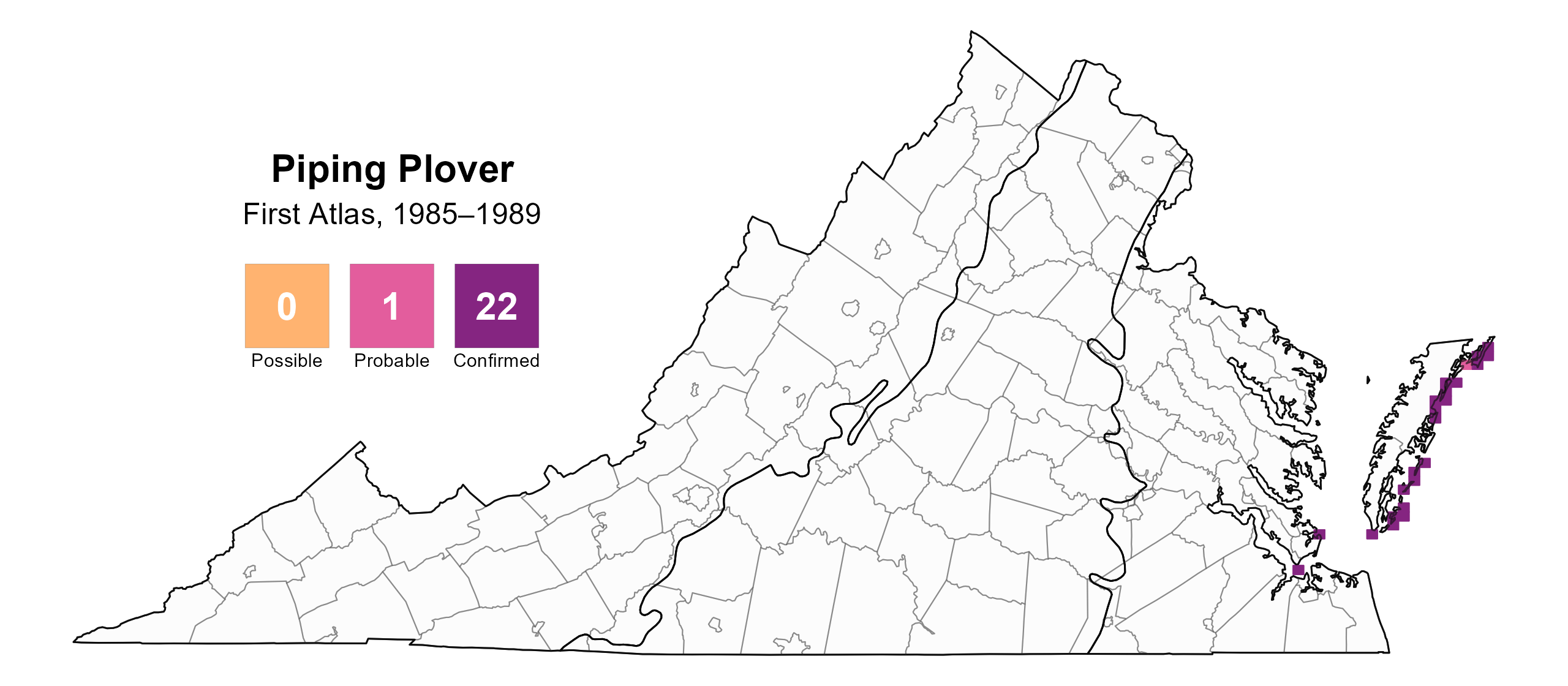

During the Second Atlas, Piping Plovers bred exclusively on Atlantic barrier islands, from Assateague Island in the north to Fisherman Island in the south in 21 blocks and Accomack and Northampton Counties (Figure 1). This distribution was largely unchanged from that in the First Atlas, despite the intermittent reshaping of beach habitat by storms, accretion, and erosion. During the First Atlas, there were two additional small, disjunct breeding populations on the Western Shore at Grandview Nature Preserve in Hampton and at Craney Island dredge site in Portsmouth (Figure 2). These breeding populations were not present during the Second Atlas and have been absent from these sites since 1997.

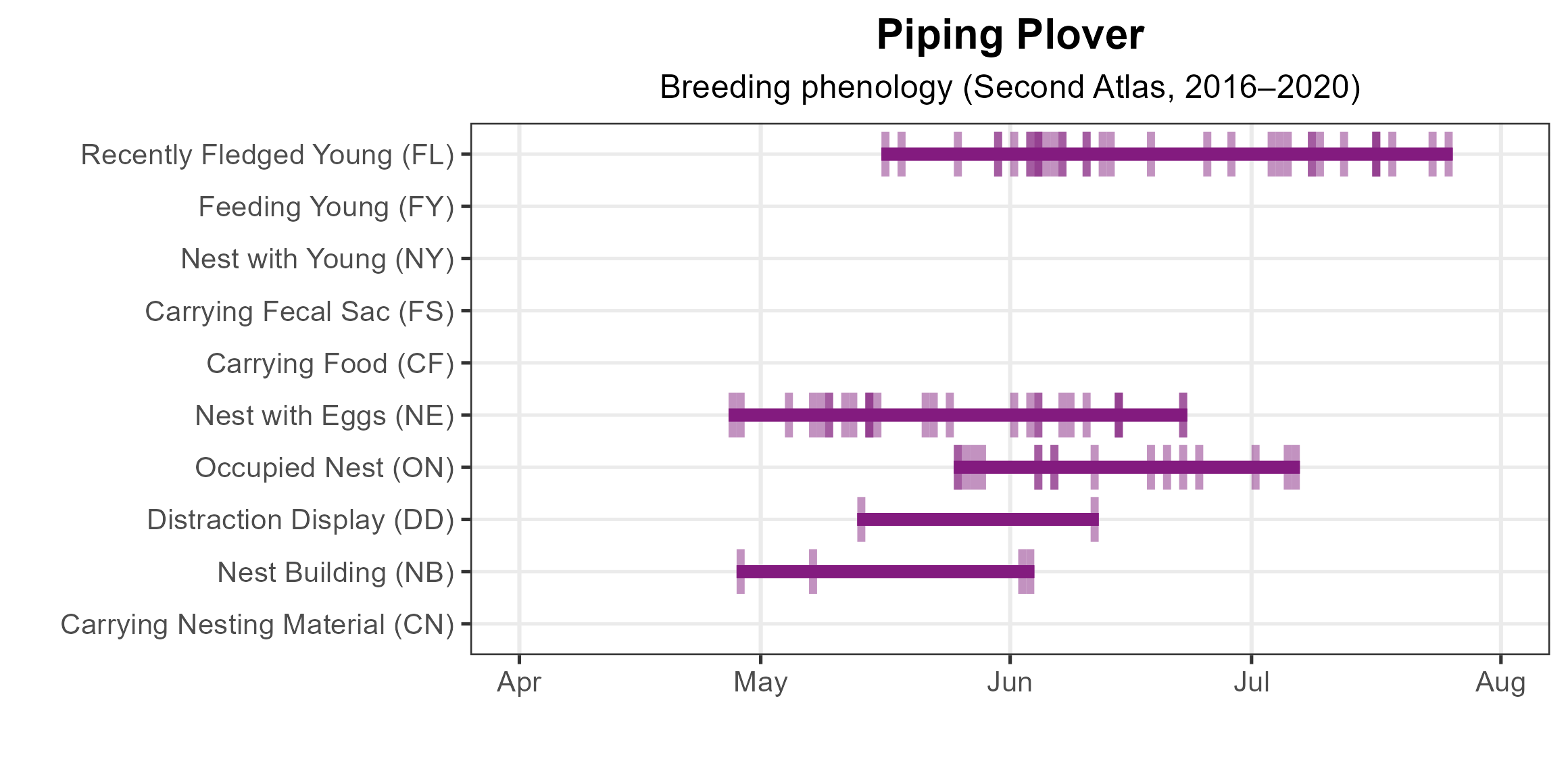

Piping Plover nests had eggs from April 27 to June 22 (Figure 3). Chicks are precocial, meaning they can run within a few hours of hatching and only become capable of sustained flight around 28 days after (Elliot-Smith and Haig 2020). Young were observed from May 16 to July 25.

For more general information on the breeding habits of this species, please refer to All About Birds.

Figure 1: Piping Plover breeding observations from the Second Atlas (2016–2020). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 2: Piping Plover breeding observations from the First Atlas (1985–1989). The colored boxes illustrate Atlas blocks (approximately 10 mi2 [26 km2] survey units) where the species was detected. The colors show the highest breeding category recorded in a block. The numbers within the colors in the legend correspond to the number of blocks with that breeding evidence category.

Figure 3: Piping Plover phenology: confirmed breeding codes. This graph shows a timeline of confirmed breeding behaviors. Tick marks represent individual observations of the behavior.

Population Status

Piping Plovers are monitored alongside Wilson’s Plovers (Charadrius wilsonia) and American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliates) by a partnership of several organizations, including the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), as part of the annual Virginia Plover Survey.

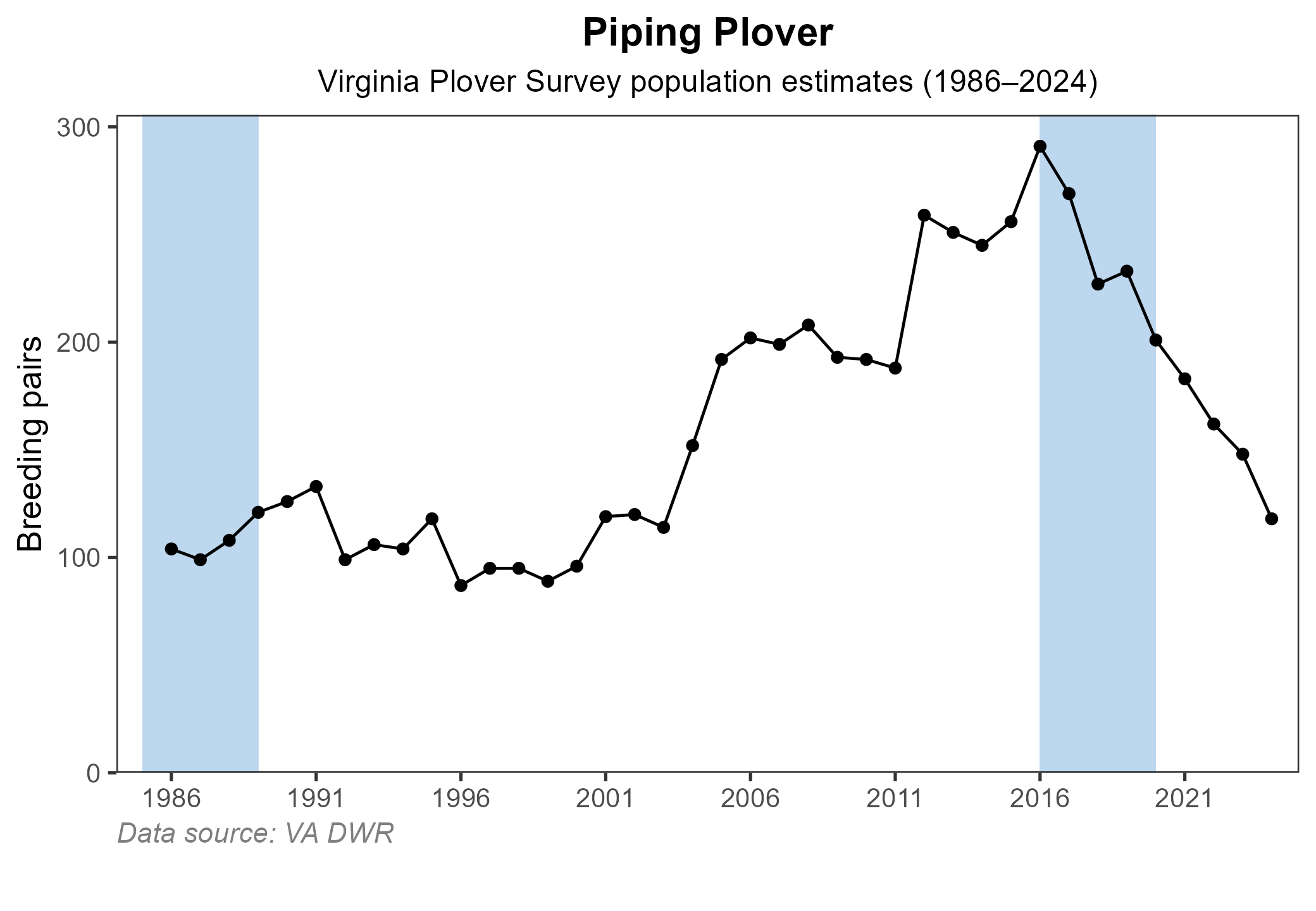

Virginia is an important contributor to Piping Plover populations. From 1986–2005, the state supported between 6–13% of the Atlantic coast breeding population (Boettcher et al. 2007). More specifically, from 1986 to 2003, the annual breeding population averaged 106 pairs. Numbers began increasing following habitat gains incurred by Hurricane Isabel that struck the coast in September 2003 and subsequently peaked at 291 pairs in 2016 (Figure 4). Since 2016, however, the population has declined by 59% (Boettcher et al., unpublished data). Despite widespread habitat protection on Virginia’s barrier islands, most of which are owned and managed for conservation by TNC, USFWS, and the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, recovery has stalled.

Figure 4: Piping Plover population trend for Virginia’s Coastal Plain. This chart illustrates the number of breeding pairs as estimated by Department of Wildlife Resources surveys. The vertical light blue bars represent the periods corresponding to the First Atlas (1985–1989) and Second Atlas (2016–2020).

Conservation

The Piping Plover is classified as a Tier I Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Critical Conservation Need) in Virginia’s Wildlife Action Plan and is listed as threatened in the state due to their declines for which there are several possible causes (VDWR 2025). Piping Plovers rely on overwash fans created by storms for nesting and feeding. These open, sparsely vegetated areas provide critical access to intertidal mudflats, especially for chicks. In the absence of major storm events, vegetation regrows in overwash zones, reducing habitat quality for plovers (NPS 2021). Other pressures include nest loss from flooding events, predation, and limited food availability.

Virginia’s barrier islands offer one of the best-protected stretches of coastline for Piping Plovers in the U.S. Plovers in Virginia are at a much lower risk of off-road vehicles, fireworks, off-leash dogs, or other recreation destroying their nests (Ruth Boettcher, personal communication). On Assateague and Assawoman Islands, wire exclosures are erected by nest monitors to prevent depredation of eggs and chicks, and these exclosures have improved hatching success but may not be enough to offset their decrease in productivity (NPS 2021). Avian predators include American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) and gulls. Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge staff engage in limited gull control to protect nesting Piping Plovers. Nonavian predators include red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), raccoons (Procyon lotor), opossums (Didelphis spp.), coyotes (Canis latrans), domestic dogs (Canis familiaris), and especially domestic cats (Felis catus) (Elliot-Smith and Haig 2020). The USFWS, TNC, NASA, and VDWR support annual mammalian predator control efforts on key nesting islands.

While the broader Atlantic Coast population has met abundance goals set by the USFWS recovery plan, these gains can easily be lost. In the long-term, sea-level rise poses a serious threat: projections suggest that Assateague and Chincoteague could lose 50–90% of their wetlands and plover foraging habitats within 120 years (Lostritto and Taylor 2015).

Effective conservation of Piping Plovers will require adaptive strategies to maintain early-successional beach habitat and ensure access to feeding areas. Predator management, habitat restoration, and continued monitoring remain essential. Public education is also critical. Beachgoers can support recovery efforts by staying out of posted nesting areas, keeping dogs leashed or off beaches entirely, and giving space to any bird displaying defensive behaviors.

Interactive Map

The interactive map contains up to six Atlas layers (probability of occurrence for the First and Second Atlases, change in probability of occurrence between Atlases, breeding evidence for the First and Second Atlases, and abundance for the Second Atlas) that can be viewed one at a time. To view an Atlas map layer, mouse over the layer box in the upper left. County lines and physiographic regional boundaries (Mountains and Valleys, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain) can be turned on and off by checking or unchecking the box below the layer box. Within the map window, users can hover on a block to see its value for each layer and pan and zoom to see roads, towns, and other features of interest that are visible beneath a selected layer.

View Interactive Map in Full Screen

References

Boettcher, R., T. Penn, R. R. Cross, K. T. Terwilliger, and R. A. Beck (2007). An overview of the status and distribution of Piping Plovers in Virginia. Waterbirds 30:138–151.

Elliot-Smith, E., and S. M. Haig (2020). Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.pipplo.01.

Lostritto, P. L., and G. E. Taylor Jr. (2015). Effects of sea level rise on foraging habitat of the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus): A geographic information systems approach. Maryland Birdlife 64:23–41.

National Park Service (NPS) (2021). Assateague Island National Seashore resource brief – Piping Plover. https://www.nps.gov/asis/learn/nature/resource-brief-piping-plover.htm.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (VDWR). 2025. Virginia wildlife action plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Henrico, VA, USA. 506 pp.